Introduction:

One of the Holy Grails for researchers of the Bolognese fencing tradition has always been finding the existence of a tradition or an institution that could’ve supported the continuation of a martial legacy in the city. I believe that in light of recent discoveries we’re closer to achieving that goal than ever before. The key? The Viridario Academy, the Academy of the Knights of Viola, and our old stomping ground—il Casino!

Palazzino Viola; Il Casino—The Little House and Case Nuove:

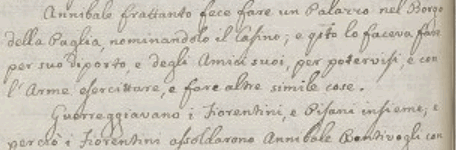

In 1497 Annibale Bentivoglio built a palazzo called il Casino (the little house); later Palazzo or Palazzino della Viola, this complex was intended in part for the martial training of key members of the Bentivogleschi faction, while a nearby facility, along via Case Nuove, was dedicated to the training of the men-at-arms in Giovanni II Bentivoglio’s mercenary company (funded by Ludovico Sforza in 14931). Stephen and I have long suspected that il Casino is where Guido Antonio di Luca trained Guido II Rangoni and Achille Marozzo in their youth2:

{1496} “Meanwhile, Annibale had a Palazzo constructed in the area of Borgo della Paglia, naming it ‘il Casino’; and he had it built for the pleasure of he and his friends, so they would be able to exercise with weapons, and do other similar things.”3

We’ll begin our journey into these hallowed fencing grounds with a look at the palazzos along via Case Nuove. Guisepe Guidicini gives us some insight as to how this corridor adjacent to il Casino was used: “{The street—Case Nuova} was called via delle case dei Malvasia, because there was a time when the nine houses that are found on the right of this street—when entering it from Borgo della Paglia—belonged to that family. Alidosi says that the aforementioned houses {Cose Nuove Complex} were inhabited by Bentivogli cavalrymen before their expulsion from Bologna. Others believe that they were built by Annibale II Bentivogli for his men, who occupied them when he stayed in the delightful Palazzo della Viola.” (Guidicini, Cose Notabili; Case Nuove del Borgo della Paglia)

In his 1743 publication Origine di tutte le strade sotterranei e luoghi riguardevoli della città di Bologna di Ciro Lasarolla, Carlo Salaroli gives a similar indication when discussing the etymology of the name via Case Nuove (today known as via Antonio Bertoloni), but broadens the scope of the soldiers housed there to the Bentivoglio men-at-arms, stating, “the Bentivoglio had built houses there (called Case Nuove) for their men-at-arms (perhaps at the time of Hannibal II when he resided in the Palazzina della Viola, not far from here).”

This is probative for a number of reasons. The commander of the Bolognese troops occupying the Case Nuove complex was Niccolò Rangoni, the father of Guido II Rangoni (Marozzo’s patron) and brother-in-law of Annibale II Bentivoglio.

Niccolò was born sometime between 1450 and 1455 to Guido I Rangoni and Giovanna Boiardo.4 At the age of 17, in 1467, he engaged in a feud with his uncles Ugo and Venceslao over the family’s territorial holdings in Spilamberto, which had been granted to his father Guido in 1454 by Borso d’Este. Together with his uncle Uguccione, Niccolò led an army of 200 lances and 500 infantry, and liberated the stronghold—which was later confirmed to him in 1476 by Ercole d’Este.5

After a few diplomatic missions on behalf of the aforementioned Ercole d’Este in 1471 and 1473, Niccolò joined Giovanni II Bentivoglio’s men-at-arms in Bologna in 1474. Then, in 1479 he was given the honor of supreme command (Captain General) of the Bolognese men-at-arms, replacing Antonio Trotti, and agreed to marry Giovanni’s daughter Bianca Maria.6 They wed in 1481, and in 1485 they had their first son, Guido II Rangoni (they would have 11 children in total, 8 boys and 3 girls).

Niccolò would have a fairly illustrious career as the Captain General of the Bolognese men-at-arms. He took part in the War of Ferrara, won a joust at Annibale II Bentivoglio’s wedding in 1487, dictated the Wars in the Romagna in the late 1480’s after the murder of Girolamo Riario, and led a number of military actions against the French in the mid 1490s. In 1492 he and his family were gifted the residence Palazzo Malvezzi Ca'Grande del San Sigismondo, which belonged to the exiled Bolognese noble Pirro I Malvezzi.7

We have some insight as to how the standing army of Bologna was composed under Niccolò Rangoni, thanks to the Bolognese Chronicler Cherubino Ghirardacci, who records the procession of Giovanni II’s company after he was given a condotta by Ludocivco Sforza in 1493: (Note on Armor8)

Giovanni returned to the market and directed the soldiers to march through the Via di Galliera to the square in an orderly manner, all armed and clad in the uniform of the Bentivogli, particularly the stockings, which were uniformly styled: one stocking red and green, the other entirely blue. The procession was accompanied by the ringing of bells, the sound of trumpets and fifes, as well as the booming of mortars and arquebuses; thus, the soldiers advanced in 19 squads...

The first squad consisted of mounted cavalry with lances and banners, numbering approximately 300.

The second squad was comprised of well-armed foot soldiers equipped with brigandines, Salet with bevor, and faulds, armed with rotella and partisan, totaling 200 men.

The third squad included foot soldiers similarly armed, but with roncha, also numbering 200 men.

The fourth squad were comprised of targonieri on foot, who were well-armed with brigandines, faulds, spaulders, harness, greaves, and a celate9, armed with a sword, each having in front of them a boy with a gold-worked targone; while others were richly worked with pearls, totaling 100 men.

The fifth squad consisted of foot lancers, well-armed; with breastplates, faulds, and a celate with bevor, numbering 200.

The sixth squad comprised well-armed crossbowmen on foot; equipped with brigandine, sallet and bevor, totaling 200.

The seventh squad included drummers and gunners in German livery, numbering 100.

The eighth squad featured trumpeters, constables, and leaders of the provisional cavalry, well-armed with golden-trimmed barding, small rotella and partisans, totaling 50.

The ninth squad, led by Alessandro Bentivoglio, included stradiotti in silk tunics of the Bentivogli uniform on sturdy horses, comprising 160 young noblemen of the city.

The tenth squad, led by Ermes Bentivoglio, consisted of 200 well-armed crossbowmen on horseback.

The eleventh squad featured drummers and young nobles of the city, numbering 300, led by Annibale Bentivoglio, all equipped with brigandines, celate, gorgets, and richly adorned emblazoned targone.

The twelfth squad followed, boasting a large number of trumpets.

Messer Giovanni Bentivoglio’s company followed in this order: first, 12 valets on splendid horses adorned with golden caparisons, silver doublets, and silk jackets in the Bentivogli uniform, embroidered in gold and silver with sparkling scales; then came Giovanni, fully armed on a magnificent courser with a golden overcoat; behind him followed 22 armed men in rich gold and silver overcoats with golden caparisons. Upon reaching the San Petronio gate, where Charles awaited with the standard, Alessandro della Volta, prior of the Senate, presented him with a beautiful and robust horse draped in curly gold cloth valued at 400 ducats on behalf of the Senate. Dismounting from his horse, Alessandro mounted the one bestowed upon him by the Senate, and as they gathered between the two ducal ambassadors, Charles advanced with the standard, followed by other armed men. Then Count Nicolò Rangone, Captain General of the Bolognese Army, lead two squads of men-at-arms and two additional squads of assorted lances, while Lord Gilberto de' Pio brought up the rear with the remainder of Bolognese soldiers, commanding three squads.

In this formation, they traversed the entire city before arriving at Giovanni's palace, where they paused until the banner was displayed at the palace windows. Giovanni dismounted at the entrance of his palace and was honored as the Poet of Poets, and a golden knight. This spectacle was regarded as one of the most magnificent displays ever witnessed in Bologna within living memory.

—Ghirardacci, pg. 270-271

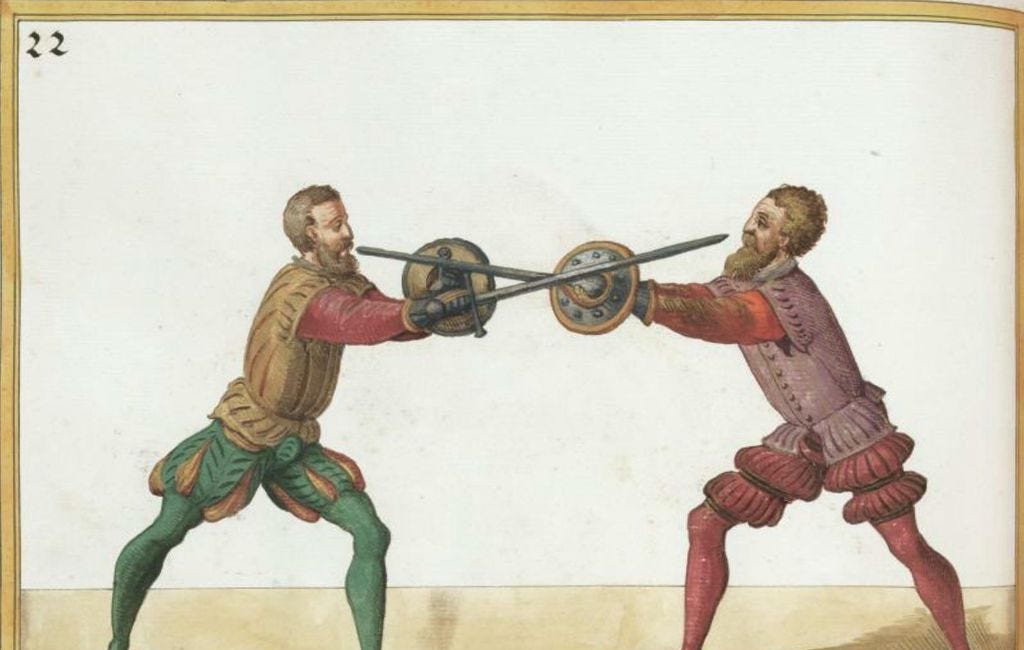

To the student of the Bolognese fencing tradition, this force composition will read like the Capitolo of Achille Marozzo’s Opera Nova: Partisan and Rotella, Roncha, Sword and Targa, and Lance.

In the late 1490s much of Niccolò’s time was spent protecting Bologna and its territorial claims from ever ambitious Conte Valentino—Cesare Borgia. In the heat of the struggle against this son-of-a-pope Niccolò died quite unexpectedly on the 29th of October 1500; he was remembered by Ghirardacci as, “a man of supreme integrity and courage,”10 as a “Friend and generous protector of men of letters and scientists,” by Argeni, and someone who Sanuto notes was, “Our most faithful.”11

Replacing Niccolò as the Captain General of the men-at-arms of Bologna was his 15-year-old son, Guido II Rangoni.12 We will dive deeper into Guido’s military exploits in our upcoming series, Death before Dishonor, so I won’t expound upon it any further here, but he left a worthy legacy in the spirit of his father Niccolò.

In 1501 while young Guido was getting his bearings as the Captain General of the Bolognese men-at-arms housed in the former Malvasia palazzos along Via Case Nuove, Palazzo Viola was gaining renown throughout northern Italy. The facility hosted a number of affluent and high-status individuals, including Sabadino degli Arienti in 1501 and the Cardinal of Ferrara, Ippolito d’Este, in February of 1503.13

Regarding Palazzo della Viola (il Casino), Pietro Giordani notes, “Annibale, the eldest son of Giovanni II Bentivoglio and Ginevra Sforza, found himself at the age of twenty-three enjoying the heights of his family's status. He picked this spot to spend time with his friends, practice with weapons—like many noble leaders of his time—and indulge in other youthful pleasures common of a prince. Anyone who owned a house or land in this area couldn’t begrudge to the powerful Annibale, who transformed it into a lovely garden filled with fruits and flowers, naming it after the many violets he planted there. Later, in 1497, he built a small but cozy residence where he could escape with his wife and kids for some leisure time.” (pg. 14-15)

In May of 1501, Sabadino degli Arienti recorded his visit to the Viola gardens in a letter addressed to the Duchessa of Ferrara, Isabella Gonzaga, titled, Descrizione del Zardin Viola in Bologna, where he noted that, “The lodge {villa} was adorned with columns of vermilion hued stone…scenes drawn from mythology and history, ranging from Latona to ‘Cincinnatus wielding a hoe' {and} Hercules in the garden of Hesperides to Venus ‘struck by an amorous arrow by her son Cupid on behalf of Adonis.” (Lucioli, pg. 243-244)

Sambin De Norcen gives us some more insightful detail: “Towards the end of the fifteenth century, Annibale Bentivoglio, son of Giovanni II, built two buildings within the city walls for his own entertainment: a small villa immersed in the greenery of the Zardin della Viola and a casino {Palazzino}. The history of the two villas is not entirely clear, but tradition identifies the building at via Filippo Re 4 with the villa. We have a detailed description of the Villa della Viola written by Sabadino degli Arienti, which does not coincide in many respects with the current building: Sabadino describes the villa as a small building with two loggias (apparently orthogonal to each other), frescoed with hunting scenes and mythological episodes or motifs from Roman history, united by the choice of a rural or woodland theme. This is followed by a small room with a wooden ceiling decorated with men and genus of a variety of violets, the predominant flower in the garden that gives the complex its name.”14

Pietro Giordani asserts in Sulle pitture d'Innocenzo Francucci da Imola discorsi tre di Pietro Giordani all'Accademia di belle arti in Bologna nell'estate del 1812 that the reason for the discrepancy between Arienti’s description and the extant palazzino is that il Casino della Viola and the lodge built by Annibale II Bentivoglio are the two separate buildings that were present on the garden grounds, and that Annibale’s lodge—which he may have commissioned the famous Bolognese architect Gaspare Nadi to construct—has likely been lost to the progress of time.15

As disappointing as that is, Giordani gives us insight that might be of some significance to the curious and clever eye of the martial arts practitioner sojourning through this material.

I’ll just say that the place really transformed because of these changes. The garden took on a French style, thanks to the lord who came back from France and only liked that country's designs. The Casino also got a makeover: it’s now a neat square shape, with well-proportioned rooms and lodges. The lodges wrap around three sides on the ground and upper floors, but not on the west side, where the staircase is located. On the upper floor, two large rooms connect to a bigger hall that gets light from the three lodges; similarly, the lower lodges light up other ground-floor rooms that sit below those halls. The building has a straightforward design, but the style is a bit rough around the edges. On the lower floor, they awkwardly placed arches on the columns, which do a good job supporting the architecture on the upper floor. To make the Casino more comfortable for modern living, they closed off the loggias, except for the one on the ground floor to the east where you enter; they added more rooms, and honestly, they didn’t hold back on covering up so many beautiful works by some really talented painters.

Giordani, pg. 21-22

The entire second story of the palazzino was rebuilt multiple times through the 17-19th centuries. What we see today is model in the French style, which was reconstructed in the 20th century to match the form of the building prior to it’s partial destruction during World War II. On account of this, it’s my belief that the familiar image of Marozzo drawing a summoning circle on the title page of his 1536 publication features the original shape and construction of the Casino della Viola in the background—before centuries of reconstruction and redesign yielded its modern form.

Most notable is the lower portion of the building, which remained largely intact, and bears a striking resemblance the the extant Palazzo. To this we can add the fact that the Palazzo depicted in the image is free standing, not adjacent to other buildings, and surrounded by gardens, which was fairly uncommon in a city as tightly packed and heavily developed as Bologna.

Today the Palazzo Viola still features art by Innocenzo da Imola (1545), Prospero Fontana (1550-55), Nicolò dell'Abate, and Amico Aspertini—all works painted in the years after the Bentivoglio Signoria.

Circling back to the Bentivoglio, in another letter between Sabadino degli Arienti and Isabella d’Este, dated June 10th, 1501, Arienti provides some context that elucidates the choice of the famous violet gardens. He recounts another trip to the Palazzo with Annibale II Bentivoglio’s wife Lucrezia d'Este Bentivoglio, wherein he states that the illustrious lady of Ferrara was called Viola for her beauty.16 Lucioli notes that Annibale, in a show of love and affection, dedicated the violet gardens to his bride Lucrezia in 1497.17

Alas, the love, romance, and martial excellence of the Bentivoglio court wouldn't last. After the family’s expulsion from Bologna in 1506, the building and its immaculate gardens were either left unoccupied or used for the training purposes of the standing Papal army in the city.

Giordani notes that it was eventually given over to the Salicini family because they owned orchards adjacent to the garden. Guidicini states that in 1497 it passed to the Pepoli and Salicini families, which I believe is a mistake, and the record is supposed to state that the Pepoli and Salicini took ownership in 1507. It's unlikely that the Bentivoglio would have sold the facility the year of its completion, and the fact that there is a clear record that Annibale II and his family used the facility regularly after 1497 further substantiates this notion.

To that point, the date 1507 makes sense historically, because many of the Bentivoglios’ assets were claimed by the Church or families supporting Pope Julius II, especially after the Bentivoglio recklessly attacked Bologna in the spring of that year and in return were banished from the city while bounties were placed on their heads. The Pepoli were a key part of the Papal contingent defending Bologna, before realigning themselves with the Bentivoglio in 1508. They were also related to the Bentivoglio through Elisabeta Bentivoglio, the daughter of Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio, and three records in the archives dated in the fall of 1540 show that the Pepoli family sold the property, denoting ownership.

Academia del Viridario:

In 1512, the Palazzo and its gardens were leased by the Pepoli and Salicini families to Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, who used the grounds to entertain his outfit known as the Academia del Viridario (founded in 151118). This was the same name he would give his 1513 chivalric genre poem (completed in 1504), which contains hallmarks of the Bolognese fencing tradition: notably sword and small buckler performed in three assalti and a variety of mezza spada techniques.19

Lucioli asserts that the motto of the Viridario institute, E SPE IN SPEM (“From hope to hope”), and its logo, the laurel plant, were derived on account that, “Achillini, regarded as "the longest-lived of the Bentivoglio scholars," continues to harbor hope, even against all odds, for the restoration of the lordship. This hope (e spe) gives rise to a further aspiration (in spem) for a new golden age,”20 and “In this context, the endeavor of the Accademia del Viridario encapsulates all the meanings associated with the laurel, a symbol of the protection that Achillini aspires to receive from the Bentivoglio, both for the activities of the cenacle and, more broadly, for his own homeland.”21

There is a lot to unpack here. First, we’ll start with the fact that Giovanni Filoteo Achillini was “regarded as the longest-lived of the Bentivoglio scholars”. This is something we have long speculated and can now confirm. This means that his sword and small buckler section in Viridario is almost undoubtedly an observation of Guido Antonio di Luca’s fencing school in Bologna. A small point, for sure, but a meaningful one in the grand scheme of things.

It also provides some significant context for the purpose of Achillini’s academy. The name of his poem, Viridario, and the academy he founded, means garden. While it's easy to make the superficial leap and conclude that Achillini wittily drew upon the setting of his newly founded institution, his prose in Viridario paint a more storied and dynamic picture. The Viridario was the garden of the mind, the picturesque landscape of the perfect Bentivogleschi courtier, and his academy was a revival of that ethos.22

Thus, the metaphor of the garden conceals the true essence of a poem that is only superficially mythological and chivalric; rather, it should be classified within the genre of silvae, polyanteae, and indeed viridarii—those types of texts that Paolo Cherchi has characterized as "secret manuals", which Achillini interprets as a comprehensive encyclopedic summa of the knowledge of his era. As seen in the Fidele, the revelation of wisdom in the Viridario results from a progressive and ascending journey, guiding the protagonists toward an increasingly profound understanding.

Lucioli, pg. 241

So, what does Achillini’s garden of the mind look like? What subjects would’ve been the focus of his Academy in its attempt to construct the ideal Bentivogleschi courtier? His epic, Viridario, gives us some insight:

I've done my best to follow the Horatian advice and adapt my verses to the delightful Viridarium. In the structured tale of Minosso, the King of Crete, among other things I've carefully chosen and crafted, I’ll share how virtuous rulers and their subjects should commendably govern their innermost selves. By using sound reasoning, both mortal and truly immortal, I’ll unveil the great mysteries of hidden Necromancy23, the two-headed mountain, and the famed source of Parnassus, along with the nine Muses24; daughters of Jupiter, various passionate Loves, fierce wars, remarkable local memories25, part of the secret strikes of fencing26, the fitting sacrifices to the ancient Gods, numerous genuine experiments, maritime adventures, fierce naval battles, just voyages, and marine ports, the microcosm, and the Minor World, the individual Trinity. I’ll also sing the praises of my most esteemed, learned, and warlike homeland, and finally, we’ll discuss our contemporary scholars of the Apollonian faith. Amid these lofty themes, I’ll weave in playful and enjoyable passages, mixing and varying them freely, so that every honest reader can find joy and benefit where they may.

Achillini, Viridario; pg. 2r-2v

We can only speculate, but if Lucioli is correct that Giovanni Fiolteo Achillini was trying to reignite the torch of the Bentivogleschi court, then it’s not much of a leap to assume he employed a fencing master familiar with the fencing tradition synonymous with the family to complete his curriculum in the Academia del Viridario—it was a core tenet of his garden of the mind, after all.

This likely would not have been Achille Marozzo, but it could have been a role fulfilled by Antonio Manciolino and/or Angelo Viggiani. The complexity of Manciolino’s Opera Nova and breadth of Viggiani’s lo Schermo certainly fit the narrative of the Viridario quite well, and they read like worthy representatives of Achillini’s reimagined court; as Viggiani’s muse Boccadiferro alludes, when discussing the combination of natural philosophy and martial knowledge, “it’s like gold paired with a precious gem.”

Setting martial matters aside for a moment, records indicate that the Academia del Viridario achieved Giovanni Filoteo Achillini’s aims—at least in one case. In the biography of Sebastiano Serlio, Maria Beltramini notes, “Count Lambertini, a cultured member of the Senate and the Bolognese cultural elite gathered in the Accademia del Viridario, may have played a significant role in promoting his social and professional progression, as well as in directing his attention towards reformist religious positions, which he would later have the opportunity to develop.”27

Other suspected members or contributors of the academy include Giulio Camillo Delminio, the afore mentioned Count Cornelio Lambertini, Leandro Alberti, Romolo Amaseo, Alessandro Manzuoli, Achille Bocchi, and the convicted heretic Lisia Fileno; aka Camillo Renato, who all appear in Achillini’s 1536 Annotationi della volgar lingua.28

Much of the storied history of the Academia del Viridario has been lost or has yet to be recovered, but it's certainly an intriguing middle ground to stage the rest of our story.

d’Academia de’Cavallieri della Viola:

As mentioned, the Pepoli family eventually sold the Palazzo on the 10th of September 1540, recorded in a deed dated 7 October.29 Then, on the 10th of December, the buyer, Cardinal Bonifazio Ferraeri, Piedmontese Bishop of Ivrea and lord of Masserano, officially launched his ecclesiastical college on the grounds of the Viola Gardens called the Ferrerio College, where he built a number of outlying buildings. Almost two decades later in 1561, the College, then owned by his son Besso Ferrari, gave license for the Palazzo della Viola and part of the gardens to be used by a new institution founded by the Bolognese knight Ettore Ghisilieri. Ghislieri, along with Ottavio Bianchetti, Vincenzo Legnani, Pirro III Malvezzi, Vincenzo Marsili30 and nine other nobles of the city, established what both Guidicini31 and Giordani32 claim was the successor to the Academia del Viridario—d’Academia de’Cavallieri della Viola.

The Knights of Viola!

Dal N.2954 al N.2960 – Orto della Viola, e Collegio Ferrerio.

“It is said that the Accademia del Viridario had its foundation and residence in the Palazzino by Giovanni di Filoteo Achillini in 1511, whose emblem was a laurel plant with the motto — E SPE IN SPEM — When this one died out, another one arose, called the Viola, or the Desti, instituted in July 1561 by the knight Ettore Ghisilieri for chivalric exercises, jousts, tournaments, barriers, etc.”

—Giuseppe Guidicini

According to Guidicini, “Their emblem depicted a rooster grasping a laurel crown, with the motto — Vigilandum — and beneath it — i Desti.”

The aim of the outfit was to reclaim the martial legacy of Bologna, and to reinvent the resplendence of the Bentivoglio court. To do this, the knights of the academy practiced with a variety of different arms, jousted, and engaged in combat at the barrier—all arts that were losing their storied place on the field of battle, but were deemed irreplaceable for cultivating a well-rounded martial mindset.33 Alongside this practice, members of the Academy would also endeavor to cultivate their viridario by studying the classics and the principles of virtue, while also entreating in rhetorical dialogue and writing poetry.

This tripartite theory of refinement through the mastery of the martial arts in conjunction with the tenants of scholasticism as a means of preparing for war is discussed in Giovanni dall’Agocchie's Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre. There, dall’Agocchie makes an argument against the nay-sayers who deride the pursuit of excellence in ‘dying’ arts:

Lep. Explain to me, I pray you, the reason why it’s the foundation of the military art.

Gio. One can interpret this name in a general or in a particular sense. In general, for any sort of militia. In particular, for one-on-one combat. But any time that it’s not expressed otherwise, one must take it to refer to one-on-one combat. In general, then, (as I told you) one takes it to refer to any sort of militia, since the military art consists of nothing other than in judiciously and prudently defending oneself from the enemy and harming him, whether in the cities, or in the armies, or in any other place; because this word “fencing” means nothing other than defending oneself with a means of harming the enemy. Thus it is clear that it can be taken generally for every kind of combat…

Now, these who defend themselves against their enemies, simultaneously beating aside their insolence instead with art and mastery, are properly said to be protecting themselves when it comes to pass that they utterly save themselves and the republic. And in this action prudence holds the chief place. While on the contrary, whoever faces his enemy’s fury without art or mastery, always ending up rashly overcome, finds himself not defended, but rather derided for it. Accordingly, if you do not grant prudence a place of honor, rather holding it in no esteem, then this art, which is founded and based on prudence, will usually be seen to hold little value for you.

Giovanni dall'Agocchie (Swanger, pg. 4-5)

Among the Academy’s ranks were some of the greatest knights in all of Europe34; notably, Pirro III Malvezzi, Vincenzo Legnani, and perhaps Fabio Pepoli, who valiantly led the Papal forces in the resounding victory at the Battle of Moncontour in 1568.

Pope Pius, having been persistently solicited for assistance by Charles IX, King of France, against the Huguenot heretics who were severely troubling him, dispatched four thousand five hundred well-organized infantry and nine hundred cavalry under the command of Sforza Sforzi, Count of Santa Fiora. Among the cavalry were Vicenzo Legnani, Senator of Bologna, serving as Master of the Field of the Cavalry, and Fabio Pepoli, Count and Commander of the Venetians, who at that time commanded one hundred lances and two companies of infantry, equal in number to those led by Pirro Malvezzi, Count and Senator. Both leaders brought with them numerous Bolognese gentlemen and citizens from various strongholds, all of whom gathered in the presence of the Duke of Anjou, brother of the King of France. Despite being outnumbered, he achieved victory in a significant battle at Moncontorno in Poitiers, where thirteen thousand infantry and one thousand five hundred Huguenot cavalry from the army of Gasparo Coligni, former Admiral of France and leader of the Huguenot heretics, perished. In contrast, the Catholic forces suffered fewer than four hundred casualties, a fact that can genuinely be regarded as a miracle of God, who at that time appeared to favor the righteous cause of the Catholics, perhaps due to the fervent prayers offered by the Pontiff.

Vizzani (1568), pg. 68-69

Later, between 1570-1573, another host of Bolognese nobles would endeavor to venture abroad—led once again by the storied captains Pirro III Malvezzi and Fabio Pepoli. Our stalwarts of Bolognese prowess were accompanied by Luigi Pepoli, Camillo and Pasoto Fantuzzi, Cesare Bentivoglio, Alessandro and Paolo Zambeccari, Bonifacio Bevilaqua, Marcello da Bologna, and Antonio Ercolani. This noble host served in the combined Christian fleets during the War of Candia, which featured the infamous naval battle of Lepanto.35

As one traverses the tales of the Knights of Viola, anyone well versed in our work will no doubt recognize the familiar names of families steeped in the history of the rise of the Bentivoglio Signoria: the Malvezzi, Pepoli, Bianchetti, Gozzadini, Fantuzzi, Castelli, and Ghisilieri. All of these families had their fair share of reasons to hate the Bentivoglio and long for their destruction at the turn of the 16th century, but the subsequent years of directionless meandering and second-rate standing in the wake of the Bentivoglios’ collapse left many of the later generations wondering what could have been.

Italy at this time was a shell of its former glory. Fifty years of conquest and subjugation had stripped the peninsula bare of its Renaissance luster. Many of the great lords and noble houses that once characterized the height of the golden age were gone or scattered to the wind. In their place came Imperial advisors of German and Spanish origin, and corrupt Papal officials wielding repressive ecclesiastical standards. Thus, as the Italian Wars came to a close, many of the old guard reunited, and looked to the past to reclaim their future.

Similar to the foundation of the Academia de’Cavallieri della Viola in Bologna, there was the enshrinement of the Florentine dell'Ordine De' Cavalieri di Santo Stefano, also in 1561, and it's possible that Salvatore Fabris’ Order of the Seven Hearts falls within the same realm of chivalric re-imagination.

When the noble knights of the Academy della Viola weren’t at war in some capacity or another (which they frequently were), they enjoyed putting on demonstrations of their martial prowess and would adorn these demonstrations with intricate allegories that highlighted the depths of their classical educations. The Bolognese chronicler Pompeo Vizzani, who was himself a member of the Academy31, expounds on the breadth of the Knights’ repertoire:

During that period, the populace was significantly distressed by the famine, which was acutely felt throughout the year. Nevertheless, the gentlemen continued to host feasts, tournaments, and jousts, as many had recently formed an esteemed society known as the Academy of the Knights of the Viola. This title was derived from their meetings in a palace owned by Besso Ferrerio, Marchese of Masserano, which had been appropriated by the merchant of the people. To avoid squandering their youth in idleness, they diligently engaged in activities such as training in arms, riding, and other honorable pursuits. Frequently, during the carnival season, or in celebration of a marriage or other joyous events, they would organize jousts, tournaments, or festivities featuring splendid inventions and extravagant expenditures.

In the carnival of 1562, for instance, various jousts were held at the Quintana, including a particularly beautiful event on Carnival Sunday. The prize for this competition was a luxurious crimson velvet pennant, along with a sword, dagger, and golden cintura, which the Anziani proposed to award to the knight who displayed the most valor on the day of the joust. The knights appeared on the field in splendid formation, fully armed and adorned with various devices and livery. All participants conducted themselves admirably, and ultimately, to the great applause of the crowd, Pirro Malvezzi emerged victorious. He received the pennant as a prize and was escorted by all the gentlemen to the villa, accompanied by the sounds of trumpets, drums, and the cheers of the assembled people. The sword was given to Hercole Malvezzi.

–Vizzani, pg. 53 (1561-1562)

As Vizzani notes, this joust preceded an immaculate presentation at the annual Carnival celebrations in 1562, planned, designed, and coordinated by the Knights of Viola—you can read the full account here. These dizzying displays became the sinews of legend, prompting over seventeen volumes to be written about their theatrics between 1562 and 1662—not including the two recorded in Vizzani’s history of Bologna.

The Bolognese citizens were enamored with the knights’ pomp and pageantry—and boy did they have a knack for both! Giovanni Rossi, the Venetian printer who moved his printshop to Bologna in 1559, became in many respects the primary propaganda arm for the Knights of Viola. In the late 16th century, Rossi published Descrittione della Festa Fatta in Bologna Nelle Nozze De Gli Ill. MI Sig. Ri IL Sig. Piriteo Malvezzi, Et la Signora Donna Beatrice Orsina: IL di ... MDLXXXIV, alongside the Bolognese artist Giovanni Battista Benacci.36

Later, another Bolognese artist, Giovanni Battista Coriolano, would illustrate the fantastic floats and processions produced by the Knights of Viola for the 1628 Carnival.37

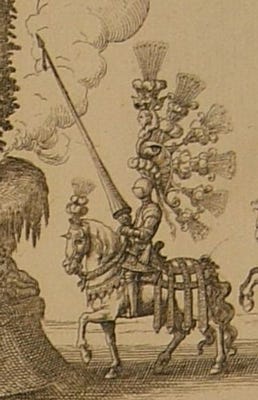

Francesco Brizio, an artist who was trained in and taught at the Bolognese school founded by the Caraccis (i.e., Annibale Carracci) called38 Accademia degl’Incamminati—instituted by the founder of the Knights of Viola, Ettore Ghisilieri39—painted and etched a number of scenes depicting the Knights in action. The image placed at the start of this section, titled, Combat à la barrière40, and Il gioco cavalleresco nella Bologna del Seicento (below), depict a public joust and combat at the barrier in the early 17th century (likely 1620 or 1628). These contemporary accounts illustrating the chivalric deeds of the Knights of Viola give us some keen insight into how the arts we’ve only been able to study as ink on a page were brought to life.

Viewing these images, the mind of the ardent Bolognese fencing scholar will instantly turn to Giovanni dall’Agocchie's chapter on the joust, and the Anonimo Bolognese’s poleaxe in armor sections.

Through the years many have argued that the anonymous author’s poleaxe section dated the text earlier—likely 15th century—and assumed it could be the manuscript edition of Guido Antonio di Luca’s Opera Schermo, but with the fresh new insight revealing the continued use of the poleaxe well into the 17th century, we can begin to take a more mature approach to dating the text—which a vocal few have already speculated belongs in the latter half of the 16th century.41

Furthermore, Giovanni dall'Agocchie’s, Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre—The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation, enlivened by this history, begins to read like a manual for the exploits of the Academy della Viola. Published eleven years after the foundation of the Academy in 1572, and dedicated to the illustrious Conte d’Castiglione Fabio Pepoli—who was likely a member of the Academy—this text highlights the three core aptitudes pursued by the practitioners of the institution: ritual violence, martial excellence, and war.

That's not all though. In 1588, Zachara Cavalcabo purchased a number of copies of Angelo Viggiani’s lo Schermo, and hired our old friend Giovanni Rossi to reprint them with a new dedication to Pirro III Malvezzi, another founding member of the Knights of Viola—Conte Fabio Pepoli’s comrade-in-arms and at times criminal co-conspirator (we’ll get into this further in the next installment of this series).

We can probably add to this list Mercurio Spezioli’s, Capitolo di M. Mercvrio Spetioli da Fermo, nel quale si mostra il modo di saper bene schermire, & caualcare, which treats with fencing and horsemanship—published in 1571 by Giovanni Rossi.

Finally, this foray also poses new questions on what impact the Knights of Viola had on the development of the fencing ideas purported by Federico Ghislieri’s Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii, given that the Academy was founded by his cousin Ettore and scores of his relatives were among the ranks of the Knights of Viola throughout their centenary existence. Along with with fencing, Federico’s text includes fighting at the barrier, the joust, and a number of knightly exercises, among other relevant topics.42

One final note regarding the characteristic crests of Cavalieri della Viola. They first debuted during the 1562 Carnival celebrations, and quickly became synonymous with the outfit.43 As the decades passed the extravagance of the heraldic motifs became more resplendent, often bordering on extreme. Interestingly, in Brizio’s paintings we can see that they weren't just reserved for floats and carnival processions. They were worn at the barrier and during the joust.

Conclusion:

Why is this so important? Because this facility—this little house with its beautiful violet gardens—links together Achille Marozzo, Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, Angelo Viggiani, and Giovanni dall'Agocchie through the figures of Annibale II Bentivoglio, Guido II Rangoni, Fabio Pepoli, and Pirro III Malvezzi who occupied its halls. The chivalric enterprises and re-imagination of Bentivogleschi court through the Academia del Viridario to the d’Academia de’Cavallieri della Viola provides a through-line of a living martial tradition. This context demonstrates not only the staying power and legacy of the tradition, but also the desire for rebirth and renewal of its vestiges.

With this knowledge we can put historiographic landmarks in the place of many of the questions surrounding the Bolognese fencing tradition, and see the art in practice in new and insightful ways. One point of interest inspired by the demonstrations of the Knights of Viola will surely be the performative aspect of the art. This was not a novel concept. For instance, Ghirardacci records the following Carnival demonstration in 1506:

1506:

Then, on Carnival Monday, he took part in the Carnival and gave battle alongside some groups of young men. They were armed with a Rotella, carrying two lances without iron, and a sword at their side that had no edge or point. Divided into two teams, they began by throwing their spears with haste and then proceeded to play {giuocare} with swords. Once that game wrapped up, two more teams appeared.

—Cherubino Ghirardacci, pg. 342

Similar public demonstrations were held in the 1480s and 1490s, like the large mock battle held with sword and buckler at the wedding feast of Annibale II Bentivoglio, and the sanctioned sword and buckler duel held during the Carnival celebrations in 1493:

1493

On 19 September Giovanni Bentivogli gave a free license to Bernardino dal Guanto from Mantua and a Spaniard to {fight a duel}; On Carnival day, they appeared in the market clad only in their shirts, armed with sword and buckler, and engaged in combat. When both were wounded, Giovanni intervened, and did not allow them to continue any further, instead compelling them to reconcile.

—Cherubino Ghirardacci, pg. 273

Jousts had long since been a part of the martial ethic of Bologna. The first record of a Bolognese joust that I have found was in 1147. This was followed by a few records in the 13th and 14th centuries, before five jousts between 1397-1417 kicked off the 15th century.

Ghirardacci records three jousts in 1440: one on the 30th of February, won by Floriano di Gratiolo Accarisi; another on the 20th of June, won by Floriano di Gratiolo Tossignani; and the final one in September, won by Ludovico di Gasparo Malvezzi. In 1441, there were two jousts, both won by Ludovico Malvezzi, who a year later also won the the inaugural joust on behalf of Niccolò Piccinino. Between 1443 and 1487 there were 12 more jousts, culminating in the massive multi-district joust in honor of Annibale II Bentivoglio’s wedding. This preceded four more jousts over the next decade: one in 1489, won by Francesco del Capitanio; another in 1490, won by Cesare Gozzadini; and two more in 1492, won by Galeazzo da San Severino and Antonio dalla Volta.

The winners of the jousts in the 15th century read like a list of the future Knights of Viola: Pepoli, Malvezzi, Bianchetti, Gozzadini, and dalla Volta. Which makes sense. This was a class of individuals who made their living and staked their livelihood on their status as knights. They were also the ones most affected by the societal changes forced upon them by the progress of warfare during the Italian Wars.

Speaking of the Italian Wars, when Charles VIII crossed the Alps in 1494, young Italian nobles didn't need mock combat to satisfy their martial urges anymore—war was omnipresent. As such, there are unsurprisingly few jousts on record in Bologna after 1493. Not to say that jousts didn't happen, or that the martial art of jousting wasn't being practiced; it just wasn't being done publicly. Of course, the general appetite for the romance of the spectacle had probably worn off with the cart loads of bodies.

This tells us quite a bit how the hot and cold progressions of warfare dictated the production of fencing treatises. For example, we know that it took Marozzo 30 years to finish his Opera Nova (1516-1536). Manciolino tried to publish in 1519, and had his first production between 1522-1523, but would not see his full production run until 1531.

The early Bolognese authors, Achillini included, were often swept up in the tumult and chaos of warfare, and had to put their plans on hold. Viridario was completed in 1504, but Achillini waited for it to be printed until 1513, when Annibale II Bentivoglio had returned to power in Bologna—the timing was not coincidental.

Manciolino’s Opera Nova likely fell victim to the heightened tensions of the 1520s that culminated in the sack of Rome, and the death of his patron Don Luis Fernandez de Cordoba. It only found its place after Charles V’s coronation, amidst the heightened interest in the Bolognese arts.

Lastly, Marozzo's Opera Nova was completed during a period of transition and relative quiet for his patron Guido II Rangoni. This came after he switched from French to Imperial service in 1532. During this period the most exciting thing recorded in his life—until his switch to Papal service in 1536—was a possible duel with a man named Piermaria dei Rossi in 1533.

The wandering nature of Rangoni’s life paints a storied tale. He tread condotta after condotta, until he had served so many masters—ever valiantly—that his funeral procession looked like a United Nations summit with all the standards of the principalities he had represented. This was the result of the collapse of 15th century Italian order.

Where his father Niccolò came to loyally serve the Bentivoglio before all else, and in his role as Captain General was only called to service outside of Bologna when her allies, friends, or strategic interests were threatened, Guido was forced to serve the most convenient nation-state at war—countries that were always happy to have local captains to fill their ranks with native levies.

Gone were the Sforza and the Bentivoglio, the Baglioni, and (for a time) the Medici. By the mid-16th century the Gonzaga of Mantua and Farnese of Parma held the esteemed courts of the post-Italian Wars age. Yet even they couldn't avoid falling victim to the divisive influence of competing global powers and saw their heights reach a sharp and sheer decline.

This new Italian reality had two outcomes: attempts by the nobility to reinvent the old martial ethic—especially after the death of Charles V—and, for the less fortunate, banditry. Of course, those who longed for power often leveraged both sides, as we’ll see in our forthcoming article on the life of Fabio Pepoli.

If you want to keep following our work, subscribe. If you'd like to help us sustain our research endeavors consider a paid subscription. All proceeds go to material directly related to the work we publish for free.

Now there is more than one more way you can support our work. If you enjoyed the tales of the Knights of Viola, the Academy del Viridario, or il Casino, check out our related merchandise!

Link to the Art of Arms Merchandise

Appendix:

Palazzo della Viola And Case Nuove:

Dal N.2954 al N.2960 – Orto della Viola, e Collegio Ferrerio. Dai Cartigli del Comune di Bologna Palazzina della Viola; Dalle “Cose Notabili”: di Giuseppe Guidicini

Viridario:

d’Academia de’Cavallieri della Viola:

Pompeo Vizzani’s, Historie di Bologna

I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria · Volume 3

Tournament in 1578: Torneo fatto sotto il Castello d'Argio da' SS. caualieri Bolognesi il di IX. febraio 1578 c.1

Demonstration in 1628: Amore prigioniero in Delo

Digitized Bolognese Chronicles:

Della Historia Di Bologna Volume 2, By Cherubino Ghirardacci

Della Historia Di Bologana Volume 3, by Cherubino Ghirardacci

Pompeo Vizziani’s, gentil'huomo bolognese Diece libri delle historie della sua patria · Volume 2

Pompeo Vizzani’s, Historie di Bologna

I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria · Volume 3

Works Cited:

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. pg. 68. Digital.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo II (1500-1521). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Historia di vari successi d’Italia e particolarmente della citta di Bologna. Volume III. MS Codex 1462. University of Pensylvania Libraries. Digital.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Della Historia Di Bologna. Italy, Giovanni Rossi, 1657. Digital.

Achillini, Giovanni Filoteo. Viridario de Gioanne Philotheo Achillino bolognese. N.p., n.p, 1513.

Bianchi, Tommasino de. Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti. Italy, Pietro Fiaccadori, 1862. Volume 5. Digital.

Bianchi, Tommasino de. Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti. Italy, Pietro Fiaccadori, 1862. Volume 8. Digital.

A Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Bologna. Netherlands, Brill, 2017.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Print.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Amorini, Serafino, and Bosi, Giuseppe. Manuale storico-statistico-topografico della arcidiocesi Bolognese. Italia, n.p, 1857.

Canetoli, Floriano. Tomo II - Arme gentilizie delle famiglie nobili forestiere aggregate alla nobiltà di Bologna.Presso Floriano Canetoli, 1793. MLOL. https://arbor.medialibrary.it/item/f72a8dbe-60ec-4dfc-98ec-de3d2d0b918f. Digital.

Canetoli, Floriano. Tomo IV, parte I - Supplemento alle arme gentilizie delle famiglie nobili bolognesi. Presso Floriano Canetoli, 1793. MLOL. https://arbor.medialibrary.it/item/eac892d7-58a5-4251-9295-ede44f74812e. Digital

Canetoli, Floriano. Tomo I, parte I - Arme gentilizie delle famiglie nobili bolognesi paesane. Presso Floriano Canetoli, 1793. MLOL. https://arbor.medialibrary.it/item/d29eb59a-adcc-4f3d-bba2-5dbe8c1fcbcc. Digital.

Swanger, Jherek. Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Dell’Arte di Scrimia, “The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation”, lulu press, May 5, 2018. PDF.

Guglielmotti, Alberto. Marcantonio Colonna alla battaglia di Lepanto per il p. Alberto Guglielmotti. Italy, F. Le Monnier, 1862.

Atti e memorie - Deputazione di storia patria per le provincie di Romagna. Italy, Presso la Deputazione di storia patria., 1905.

Opuscoli Di Giulio Cesare Croce - Biblioteca Dell’Archiginnasio. badigit.comune.bologna.it/GCCroce/reader/17_X_028.htm#page/9/mode/2up.

Ridolfi, Angelo Calisto, and Grandi Venturi, Graziella. Indice dei notai bolognesi dal 13. al 19. secolo. Italy, n.p, 1990.

Sokol Books Ltd. ABA ILAB. AN ACCOUNT OF A CHIVALRIC TOURNAMENT FIRST EDITION. C16th or Adams Graesse or Brunet. Edit 16, CNC 20438. LINK.

Mazzetti, Serafino. Repertorio di tutti i professori antichi, e moderni, della famosa università, e del celebre istituto delle scienze di Bologna: con in fine Alcune aggiunte e correzioni alle opere dell'Alidosi, del Cavazza, del Sarti, del Fantuzzi, e del Tiraboschi. Italy, Tip. di S. Tommaso d'Aquino, 1847. Link.

Cronologia delle famiglie nobili di Bologna con le loro insegne, e nel fine i cimieri. Centuria prima, con vn breue discorso della medesima citta di Pompeo Scipione Dolfi ... - In Bologna : presso Gio. Battista Ferroni, 1670. Biblioteca Dell’Archiginnasio. badigit.comune.bologna.it/books/dolfi/scorri_big.asp?Id=615. Digital.

Giordani, Pietro. Sulle pitture d'Innocenzo Francucci da Imola discorsi tre di Pietro Giordani all'Accademia di belle arti in Bologna nell'estate del 1812. Italy, Giovanni Silvestri, 1819.

Lucioli, Francesco. Intorno all’Accademia del Viridario. Associazione Cultuurale Internazionale Edizioni Sinestesie; Virtuoso adunanze: la cultura accademica tra XVI e XVIII secolo. - ( Biblioteca di sinestesie ; 32). 2015. Digital.

di Giancarlo, Andenna. RANGONI, Guido il Vecchio; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 86 (2018). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/guido-il-vecchio-rangoni_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Digital.

James, Carolyn. The Letters of Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti (1481-1510). Casa Editrice Leo S. Olschki, 2002. Digital.

De Norcen, Sambin. Palazzina della Viola; Bologna, via Filippo da Re n.4. Ville Bolognesi. https://www.villebolognesi.it/le-ville-storiche/le-ville-della-citt%C3%A0/palazzina-della-viola. Accessed 11/25/2024. Web.

di Maria, Beltramini. SERLIO, Sebastiano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 92 (2018). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/sebastiano-serlio_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Digital. Accessed 11/26/2024.

di Albano, Sorbelli. Marsili; Enciclopedia Italiana (1934). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marsili_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/. Digital.

Cioni, Alfredo. BENACCI, Giovan Battista; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 8 (1966). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovan-battista-benacci_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Digital. Accessed 11/28/2024.

Del Monticello, Giovanni Pellinghelli. “In Pinacoteca Nazionale Una Mostra Sul Gioco Cavalleresco Nella Bologna Del Seicento - Il Giornale Dell’Arte.” www.ilgiornaledellarte.com/Articolo/In-Pinacoteca-Nazionale-una-mostra-sul-gioco-cavalleresco-nella-Bologna-del-Seicento, 15 Mar. 2019, www.ilgiornaledellarte.com/Articolo/In-Pinacoteca-Nazionale-una-mostra-sul-gioco-cavalleresco-nella-Bologna-del-Seicento.

Tarchiani, Gabrieli, Damerini. ACCADEMIA; Enciclopedia Italiana (1929). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/accademia_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/. Web. Accessed 11/29/2024.

Goretti, Paola. Blasoneria d’araldica piumante. Un libro di disegni del

XVII secolo della Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna; Bolletino del Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe della Piancoteca Nazional di Bologa: Numero 2. Published March 2010. aperto.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it.

Chidester, Michael. Federico Ghisliero; Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii. Wiktenauer.com.

Chidester, Michael. Giovanni dall’Agocchie; Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre. Wiktenauer.com

Chidester, Michael. Angelo Viggiani del Montone; lo Schermo. Wiktenauer.com

Chidester, Michael. Guido Antonio di Luca. Wiktenauer.com

Damiani, Roberto. NICCOLO‘ MARIA RANGONI. Condottieri di Ventura. https://condottieridiventura.it/niccolo-maria-rangoni/. Updated 27 November 2012. Accessed 12/1/2024.

Goretti, Paola. Blasoneria D’araldica Piumante. Un Libro Di Disegni Del XVII Secolo Della Pinacoteca Nazionale Di Bologna | Aperto. aperto.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it/blasoneria-daraldica-piumante-un-libro-di-disegni-del-xvii-secolo-della-pinacoteca-nazionale-di-bologna. Published March 2010. Accessed 12/1/2024.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. pg. 270

Vedendo il signor Ludovico Sforza duca di Barri la gran fortuna di Giovanni Bentivogli , che governava Bologna come ne fosse vero et legittimo signore , giudicò che , havendolo a ' suoi voti , poteva vivere sicuro da ogni insidia de ' Fiorentini et da altri signori ; si forzava tenerlo obbligato al duca , et perciò lo creò capitano di tutti li suoi soldati di qua dal Po con buonissimo stipendio , et li ma ndò lo stendardo del capitanato alli 27 d'aprile.

Guido Rangoni was born in 1485, and Achille Marozzo was born in 1484. They would've been 12 and 13 at the time of the facilities completion.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Historia di vari successi d’Italia e particolarmente della citta di Bologna. Volume III. MS Codex 1462. University of Pensylvania Libraries. Digital

{1496} “Annibale frattanto fece fare in Palazzo nel Borgo della Paglia, nominandolo il Casino; e questo lo faceva fare per suo diporto, e degli amici suoi, per potervisi, e con l’arme esercitare e fare altre simile cose.”

di Giancarlo, Andenna. RANGONI, Guido il Vecchio; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 86 (2018). Treccani.it. Digital.

Guido Rangoni lasciò al figlio legittimo Niccolò, non ancora maggiorenne essendo nato a Modena tra il 1450 e il 1455 (secondo Sanuto, Diari, 1889, III, col. 1007, nell’ottobre 1500 «è di 45 anni»), il compito di continuare la sua carriera di capitano, legato alla Repubblica di Venezia, e la fedeltà vassallatica nei confronti degli Este. La madre di Niccolò era Giovanna Boiardo, figlia di Feltrino Boiardo e quindi zia di Matteo Maria Boiardo.

di Giancarlo, Andenna. RANGONI, Guido il Vecchio; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 86 (2018). Treccani.it. Digital.

In giovane età, subito dopo la morte del padre (1467), entrò in contrasto con gli zii paterni Ugo e Venceslao per il godimento dei feudi concessi alla famiglia dagli Estensi nel Trecento e in particolare per il castello e la località di Spilamberto, possesso comune fra i Rangoni. I beni nella fortezza erano stati riconfermati ai membri del casato nel 1454 da Borso d’Este. Alleatosi con Uguccione Rangoni (anch’egli suo zio, a capo di un contingente di ben 200 lance e 500 fanti), Niccolò cacciò Ugo e Venceslao dalla piazzaforte, ove si erano insediati. In seguito a ciò Ercole d’Este, fratello di Borso, designò tre giuristi allo scopo di individuare e punire chi, fra i Rangoni vassalli estensi, fosse stato indicato come colpevole. I contrasti furono peraltro presto appianati, perché nel 1469, in occasione del soggiorno a Ferrara dell’imperatore Federico III, Niccolò comparve a fianco di Ugo. Qualche anno dopo si vide riconfermare l’investitura del castello di Spilamberto [1476].

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. pg. 220

1479

Il senato conduce per capitano delle sue genti d'arme, in luogo di Antonio Trotto, il conte Nicolò Rangone modenese, il quale a dì primo di maggio, il sabbato, venne a Bolo gna et fu con molto honore dal senato ricevuto. Il signor Giovanni si pone in animo di dare al conte Nicolò Rangone Bianca sua figliuola per moglie; et essendo egli giunto in Bologna, ne lo fa richiedere, et piacendoli il partito, la sposa con molta sodisfattione sua et del signor Giovanni.

James, Carolyn. The Letters of Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti (1481-1510). Casa Editrice Leo S. Olschki, 2002. Digital. pg. 47.

Count Niccolò Rangoni, the last of whom was probably the most valuable source of news since he was not only an important member of the oligarchy and Captain-General of the Bolognese military forces but was Giovanni Bentivoglio's son-in-law. After the exile and murders of the Malvezzi conspirators, he and his wife were installed in the most splendid of the Malvezzi houses, the Ca' Grande of San Sigismondo, just metres from the Bentivoglio palace. When Rangoni was not in Bologna, his wife, Bianca Bentivoglio, answered Dei's let- ters and encouraged him to send news if she had not heard recently enough from him.

Bolognese Armor Terminology: (Special thanks to Moreno dei Ricci)

Celadoni: Closed Sallet or more robust version of a Celate, often paired with a Bevor

Celate: Open faced Sallet

Corrachina: Brigandine or breastplate

Falde: Faulds

Garzarini: Gorget or Bevor

Arnesi: Harness; varied pieces of armor

Fiancali: Spaulders or could indicate

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. pg. 300

1500

“Alli 29 di ottobbre il conte Nicolò Rangone capitano de ' soldati bolognesi muore . Era genero di Giovanni , huomo di somma integrità et valoroso.”

Damiani, Roberto. NICCOLO‘ MARIA RANGONI. Condottieri di Ventura. https://condottieridiventura.it/niccolo-maria-rangoni/. Updated 27 November 2012.

“Amico e protettore munifico di letterati e di scienziati.” ARGEGNI

“Fidelissimo nostro.” SANUDO

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. pg. 300

(L)asciò dopo di sè 8 figli maschi e tre femine, de' quali il primo, cioè il conte Guido, di anni 15 successe nella condutta; et acciochè fossero ben governati li soldati, Giovanni procurò che ne venisse a Bologna il conte Cesare Rangone, huomo esperto nell'armi e di gran riputazione.

Giordani, Pietro. Sulle pitture d'Innocenzo Francucci da Imola discorsi tre di Pietro Giordani all'Accademia di belle arti in Bologna nell'estate del 1812. Italy, Giovanni Silvestri, 1819. pg. 17.

Intanto mi ri- peteva la memoria che quivi il cava- liere magnanimo fu solito regalare i più pregiati ospiti : e nel 1503 a 23 di febbraio quivi accolse il cognato Ippolito Cardinale di Ferrara , giovane allora di 23 anni ; ed altre fiate as- sai altri de ' principi d ' Italia , che gli erano di amistà o di sangue congiunti .

De Norcen, Sambin. Palazzina della Viola; Bologna, via Filippo da Re n.4. Ville Bolognesi. Web.

Verso la fine del Quattrocento, Annibale Bentivoglio, figlio di Giovanni II, costruì entro le mura della città due edifici deputati al proprio svago: una palazzina immersa nel verde del “Zardin della Viola” e un casino. Non sono del tutto chiare le vicende delle due ville, ma la tradizione identifica l'edificio di via Filippo Re 4 con la palazzina. Possediamo una descrizione dettagliata della villa della Viola redatta da Sabadino degli Arienti, che non coincide per molti aspetti con l’edificio attuale: Sabadino descrive la palazzina come un piccolo edificio dotato di due logge (par di capire ortogonali fra loro), affrescate con scene di caccia ed episodi mitologici o tratti dalla storia romana, accomunati fra loro dalla scelta del tema agreste o silvestre. Segue una saletta con il soffitto ligneo decorato a uomini e geni tra le viole, fiore predominante nel giardino che dà il nome al complesso.

Giordani, Pietro. Sulle pitture d'Innocenzo Francucci da Imola discorsi tre di Pietro Giordani all'Accademia di belle arti in Bologna nell'estate del 1812. Italy, Giovanni Silvestri, 1819. pg. 14-16. {Translation digital}

Later, in 1497, he built a small but cozy residence where he could escape with his wife and kids for some leisure time. This other Casino we mentioned was reserved for his more private and solitary pleasures. Some thought it was commissioned by Gaspare Nadi from Bologna, an architect well-known to the Bentivogli family, but no writer has confirmed this. Even after reading through the detailed memoirs he kept of every event involving himself and the lords, I couldn’t find any mention of this building. The Giardino della Viola was praised early on by a notable writer, Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti, who was closely related to the rulers through various obligations. In May 1501, he described its charms and delights to Isabella Estense Marchesana of Mantua, sister of Lucrezia, who became Annibale Bentivoglio's wife in 1487. He only briefly mentioned the Casino at the end of his booklet, focusing instead on the nearby house, which wasn’t very large, where Annibale's family sometimes stayed. Many people overlooked this detail and mixed up the house with the nearby Casino. We’ll need to clarify the difference between the two as we continue this discussion. I was lucky enough to read the elegant copy of that description that Sabadino wrote out by hand for his friend Annibale Bentivoglio. However, it saddened me because, using it as my guide, I couldn’t find the house or the two ground-floor loggias adorned with painted hunts, fables, and Roman stories that Sabadino described (though the painters didn’t leave any clues). I searched for the upper rooms, where the Este and Bentivogli coats of arms were said to have been displayed numerous times, but all I could do was lament the miserable ruins that had been left in recent years; there was no trace left to suggest where what I was looking for might have been.

James, Carolyn. The Letters of Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti (1481-1510). Casa Editrice Leo S. Olschki, 2002. Digital. pg. 155-156.

Illustrissima ac Pudicissima Domina mea semper observanda, commenda- tione etc. Havendo in veneratione la Vostra Excellentia, ho preso dolce pia- cere mandare a quella una epistoletta narratrice de uno bel zardino de l'Illustre messer Hannibal Bentivoglio nominato per lezadria Viola; la quale epi- stola per il presente exhibitore grato a la Vostra Signoria Illustrissima a quella nomine meo sarà presentata. In epsa intenderà la verità de la amenità et iocundità del zardino, et come retrovandomi in questo luoco cum la illustre vostra sorella, fue recordato la Vostra Excellentia et epsa ivi disiata. La Vostra Illustrissima Signoria dunque per solita sua mansuetudine l'acepti et lega volun- tieri che non poco la prego, pregandola me duoni indulgentia se ella non fia ornata come meritarebbe la Excellentia Vostra, amantissima de virtute, che meglio non ho possuto fare, ma acepta ex gratia la mia buona desposta mente erga prefatam Vestram Excellentiam, cui me plurimum atque plurimum com- mendo, que felicius valeat cum eius Excellentissimo viro et sobole pulcherima.

Ex Bononia, X iuni MDI. Eiusdem V.rae Ex.tiae servus perpetuus Ioannes Sabadinus de Arientis

Illustrissimae ac Pudicissimae Dominae Isabelle de Gonzaga, Mantue marchionisse etc. et domine sue semper observande

Lucioli, Francesco. Intorno all’Accademia del Viridario. Associazione Cultuurale Internazionale Edizioni Sinestesie; Virtuoso adunanze: la cultura accademica tra XVI e XVIII secolo. - ( Biblioteca di sinestesie ; 32). 2015. Digital. pg. 240.

Un legame profondo fra il letterato bolognese e i Bentivoglio è inoltre confermato da un’ulteriore informazione sull’accademia felsinea fornita da Pietro Giordani, secondo cui le riunioni accademiche si sarebbero svolte presso il celebre giardino donato da Annibale II a Lucrezia d’Este nel 1497:

Giordani, Pietro. Sulle pitture d'Innocenzo Francucci da Imola discorsi tre di Pietro Giordani all'Accademia di belle arti in Bologna nell'estate del 1812. Italy, Giovanni Silvestri, 1819. pg. 20.

Ma prima ancora di cotesto cardinale Eporégiense , e fino dalla seconda partita de ' Bentivogli che li disperò di ritorno , questo fortunato luogo della Viola ( come il giardino ateniese di Academo , e l ' orto fiorentino di Ber- nardo Rucellai ) aveva graziosamente , e non senza fama , accolte le lettere ; introdottevi nel 1512 da Giovanni Filoteo Achillini , poeta non disprege- vole , e in que ' giorni celebre , che fon- dovvi l ' Accademia del Viridario.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Vuolsi che l’Accademia del Viridario vi abbia avuto nel Palazzino la sua fondazione, e residenza per opera di Giovanni di Filoteo Achillini nel 1511, la cui impresa era una pianta d’alloro col motto — E spe in spem.

Lucioli, Francesco. Intorno all’Accademia del Viridario. Associazione Cultuurale Internazionale Edizioni Sinestesie; Virtuoso adunanze: la cultura accademica tra XVI e XVIII secolo. - ( Biblioteca di sinestesie ; 32). 2015. Digital. pg. 239.

Achillini, «il più longevo dei letterati bentivoleschi»11, continua a sperare, anche contra spem, nella restaurazione della signoria: da questa speranza (e spe) discende l’ulteriore speranza (in spem) di una nuova età dell’oro.

Lucioli, Francesco. Intorno all’Accademia del Viridario. 2015. Digital. pg. 240.

In questo senso, l’impresa dell’Accademia del Viridario assomma in sé tutti i significati attribuibili all’alloro, simbolo di quella protezione che Achillini spera di ottenere da parte dei Bentivoglio, per l’attività del cenacolo e, più in generale, per la sua stessa patria.

Lucioli, Francesco. Intorno all’Accademia del Viridario. 2015. Digital. pg. 241.

Viridario, in questo caso, non indica un giardino reale, bensì la conce- zione di poema perseguita da Achillini: «E parmi fondatamente poter dire che ciascun poema, acciò che utile e delettabile sia, se debbia ad un bencomposto viridario, giardino, o paradiso assimigliare»20.

The Dark Arts of Bologna

Necromancy or Necromantia, defined in its late medieval and Renaissance form, is the act of summoning or invoking a demon or spirit to do one’s bidding. The common belief was that because Christ could command demons, so too could his followers. Thus, passages like Mark 1: 21-28

How to form a memory palace. Check out this paper by Lucioli:

Lucioli, Francesco. “LA ‘PHOENIX’ NEL ‘VIRIDARIO’. FORTUNA LETTERARIA DI UN TRATTATO DI MNEMOTECNICA.” Lettere Italiane, vol. 59, no. 2, 2007, pp. 262–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26267146. Accessed 26 Nov. 2024.

di Maria, Beltramini. SERLIO, Sebastiano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 92 (2018). Treccani.it. Digital.

Il conte Lambertini, colto membro del Senato e dell’élite culturale bolognese riunita nell’Accademia del Viridario, potrebbe aver giocato un ruolo non secondario nel favorirne la progressione sociale e professionale, nonché nell’indirizzare la sua attenzione verso posizioni religiose riformiste, che egli avrebbe in seguito avuto modo di sviluppare.

Lucioli, Francesco. Intorno all’Accademia del Viridario. 2015. Digital. pg. 243.

Questo spiega le difficoltà nel definire con precisione gli ambiti di interesse del cenacolo felsineo, ora ritenuto un sodalizio puramente letterario26, ora collegato alle passioni artistico-antiquarie del suo fondatore27, ora considerato un punto di riferimento per pensatori più o meno eterodossi, da Giulio Camillo Delminio ai dialoganti delle Annotationi della volgar lingua, trattato pubblicato da Achillini nel 153628, ossia il conte Cornelio Lambertini (presso la cui villa è ambientato il dialogo), l’inquisitore Leandro Alberti, l’umanista Romolo Amaseo, e ancora Alessandro Manzuoli e Achille Bocchi, «componenti del circolo che di lì a poco avrebbe accolto a Bologna Lisia Fileno, alias Camillo Renato, protagonista di un clamoroso processo per eresia e di un’altrettanto clamorosa fuga»29. Tra la data di fondazione dell’Accademia e la pubblicazione del dialogo sulla lingua intercorrono però più di trent’anni, un lasso di tempo che non permette di riconoscere una continuità diretta (o addirittura una perfetta identità) tra gli incontri ambientati alla mensa del conte Lambertini e le riunioni accademiche svolte nel giardino bolognese.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Si trova una memoria del 7 ottobre 1540, che Lodovico, e Baldassare padre, e figlio Pepoli, ed Ippolita Donati moglie di quest’ultimo avevano venduto il 10 precedente settembre certe case, e beni al cardinale Bonifazio Ferreri Piemontese Vescovo d’Ivrea, e Legato di Bologna a rogito di Camillo Morandi.

di Albano, Sorbelli. Marsili; Enciclopedia Italiana (1934). Treccani.it. Digital.

Vincenzo fondò in Bologna l'Accademia della Viola (1561)

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Vuolsi che l’Accademia del Viridario vi abbia avuto nel Palazzino la sua fondazione, e residenza per opera di Giovanni di Filoteo Achillini nel 1511, la cui impresa era una pianta d’alloro col motto — E spe in spem — Estinta questa ne sortì un’altra detta della Viola, o dei Desti instituita nel luglio 1561 dal cavaliere Ettore Ghisilieri per esercizi cavallereschi, giostre, tornei, barriere ecc. Il celebre torneo dato il 9 gennaio 1576 sulla piazza delle pubbliche scuole fu opera dei Desti che s’intitolò la Costanza d’Amore. La loro impresa era un gallo che teneva una corona d’alloro col motto — Vigilandum — e di sotto — i Desti.

Giordani, Pietro. Sulle pitture d'Innocenzo Francucci da Imola discorsi tre di Pietro Giordani all'Accademia di belle arti in Bologna nell'estate del 1812. Italy, Giovanni Silvestri, 1819. pg. 20-21.

{I}ntrodottevi nel 1512 da Giovanni Filoteo Achillini , poeta non dispregevole , e in que ' giorni celebre , che fondovvi l ' Accademia del Viridario . Alla quale succedette un'altra che si chiamò dei Desti , e fu detta anche della Viola , nel 1560 cominciata da Ettore Ghisilieri cavaliere di Portogallo , da Valesio Lignani cavaliere e capitano , e da altri dodici de ' primari nobili nella città . Quando io conside- ro i tempi d'ozio sonnolento , de ' qua- li certo non si potrà nulla raccontare ; mi viene invidia e rammarico , rimembrando gli affanni e gli agi , a che amo- re e cortesia invogliava que ' generosi animi , veracemente Desti ; che nelle nozze , de ' loro compagni prendevano occasione di onorare sè e la patria con giostre , tornei , barriere , o con rappresen- tazioni di poetiche favole miste di mu- siche : le quali ingegnose pompe sono dalla diligenza di Pompeo Vizzani trita- mente narrate . Ammutoliti ( dapprima per invidia , poi per negligenza ) quegli studi , pensarono i padroni del colle- gio , quando non potevano più dal Casino ritrarre fama , cavarne lucro ; e insieme col giardino lo allogarono . Quelli che dal 1758 al 97 lo tennero , come sono tuttavia nella memoria de ' viventi , il nostro parlare non do- mandano .

Goretti, Paola. Blasoneria D’araldica Piumante. Un Libro Di Disegni Del XVII Secolo Della Pinacoteca Nazionale Di Bologna | Aperto.

Così, nel 1561 si dava vita all’“Accademia dei Desti” (capitanata da Ettore Ghisilieri), subito soprannominati “Cavalieri della Viola” che prendeva come impresa un gallo reggente col becco una corona d’ulivo accompagnata dal motto latino vigilandum; scopo dell’associazione, “il tornear da scioperati”, il compimento di un apprendistato militare e, nel contempo, un allenamento costante al finto guerreggiar. Questo l’atto fondativo di un’intera stagione di parate, di belle giovinezze d’assalto, di bei scintillamenti di finzione.

Derived from Vizzani, Guidicini, Giordani among other sources:

Pirro Malvezzi, Lorenzo Malvezzi, Gironimo Malvezzi, Carl’Antonio Malvezzi, Protesilao Malvezzi, Ulisse Bentivoglio, Pirro Castelli, Alberto Castelli, Ettore Ghislieri, Alessandro Ghisilieri, Ottavio Bianchetti, Marc’Antonio Bianchetti, Vincenzo Legnani, Lorenzo Gozzadini, Vincenzo Magnani, Cesare Malvasia, Alessandro Campeggi, Giuliano Emanuelli, Rinucio Manzioli, Guid’Ascanio Orsi, Arigo Orsi, Marc’Antonio Mareschalchi, Pirro Boccadiferro, Cornelio Volta, Alfonso Rossi, Cornelio Buoio, Marsilio Buoio, Andrea Buoio, Alessandro Serpi, Pietro Magnani, Francesco Tossignani

Guglielmotti, Alberto. Marcantonio Colonna alla battaglia di Lepanto per il p. Alberto Guglielmotti. Italy, F. Le Monnier, 1862. pg. 302-304.

Quindi spedi la patente al capitan Girolamo Mariotti di Fano , perchè mettesse la sua compagnia nella Marca d ' Ancona : alli venti diè la condotta a tre altri capitani ; Filippo Contucci da Matelica , Concetto Matteucci da Fermo , e Giulio Sanfrèo da Urbino : alli nove febbrajo diputò ajutante del Capizucchi il capitano Aurelio Ala- volino di Macerata , e non guari dopo scrisse nel ruolo dei suoi capitani Andrea Cardoli da Narni , Vincenzo Olivieri di Pesaro , Orsino Ferrari e Rutilio Conti di Roma , Marcello da Bologna , Filippo da Civitavecchia , Flaminio Brandolini da Forli , Pierjacopo da Nocera , don Cesare Caraffa napoletano pronipote di papa Paolo , Vin- cenzo Galeotti di Roma , Francesco Marcia Signorelli di Perugia , Bastiano Bandini , e Pellegrino Sinibaldi di Osimo . 15 La gioventù animosa intanto , ed i soldati che ave- vano già prima militato , senza ripensare altrimenti alle durezze della passata milizia , cosi prontamente concor- sero a scriversi nelle nuove compagnie , che in pochi giorni ebbero pieni i ruoli : non solo dell ' armamento papale , che era di duemila fanti e trecento nobili ven- turieri ; ma anche dei battaglioni che i Veneziani , come sempre , cosi allora traevano dallo Stato . A me piace ricordare che nel presente anno quasi dieci mila statisti militavano all ' armata sotto la ban- diera di san Marco , guidati da quattro colonnelli o ma- stri di campo , che erano Paolo Orsini di Roma , Pro- spero Colonna di Roma , Claudio della Penna di Perugia , e Fabio Pepoli di Bologna : oltre ai quali erano quivi pure i capitani Carlo da Perugia , Gasparo d'Ascoli , Lo- renzo Narducci di Macerata , Pier Filippo da Scapezza- ro , Signorello da Perugia , Nardo da Bevagna , Ferro Romano , Costantino da Viterbo , Bartolommeo da Monte- santo , Giovanni Brancadoro da Fermo , Ruggero della Fara , Orazio Bordandini da Faenza , Francesco Coppoli da Perugia , Baldassar d'Assisi , Angelo Romano , Giulio da Spoleto , e Luigi Pepoli da Bologna . 1 " Similmente il Contarini , e in più luoghi anche il Sereno , ricordano i seguenti capitani da unirsi a quelli che ho nominati avanti . Pasotto e Camillo Fantuzzi da Pesaro , Cesare Crotti e Giammaria Riminaldi da Ferrara ; il conte Ce- sare Bentivoglio , conte Bonifacio Bevilacqua , Antonio Ercolani , Alessandro e Paolo Zambeccari da Bologna ; Ottaviano , Bonifacio e Annibale Adami da Fermo , Al- fonso Vitelli da Castello , Ortensio Palazzi da Fano , Ro- berto Malatesta da Rimini , Soldatelli da Gubbio , Ascanio da Civitavecchia , conte Jacopo da Corbara di Orvieto ; Pietropaolo Mignanelli , e Ludovico Santacroce di Roma.

Cioni, Alfredo. BENACCI, Giovan Battista; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 8 (1966). Treccani.it. Digital.

Il primo prodotto di questa nuova ditta vide la luce nel 1559, e fu l'opera dell'umanista udinese Francesco Robortello, che insegnava in quegli anni in Bologna: De vita et victu Populi Romani. La società non durò più di quattro anni (si sciolse nel 1562) e pubblicò opere di vario genere, ma non di grande mole; l'ultimo suo prodotto sembra esser stato quell'opuscolo fatto stampare dai Cavalieri della Viola in occasione delle nozze di Giovanni Malvezzi: Il torneamento fatto nelle nozze del Sig. Giovanni Malvezzi... (1562).

Goretti, Paola. Blasoneria D’araldica Piumante. Un Libro Di Disegni Del XVII Secolo Della Pinacoteca Nazionale Di Bologna | Aperto.

Di riso e vezzo e gioia

E’ infatti probabile che lo stupefacente taccuino bolognese che par rubato ai segreti di una attrezzeria teatrale di alta epoca, insista proprio su questi sottili intrecci. Avanzo qui l’ipotesi di una destinazione di carattere teatrale; naturalmente, del tipo più sontuoso. Impressionanti – infatti – i rimandi con una tra le piu’ stravaganti rappresentazioni bolognesi del primo ventennio del secolo XVII, Amore Prigioniero in Delo, [28] eseguita, per la precisione, il 20 marzo 1628.

Del Monticello, Giovanni Pellinghelli. “In Pinacoteca Nazionale Una Mostra Sul Gioco Cavalleresco Nella Bologna Del Seicento - Il Giornale Dell’Arte.”

Francesco Brizio, allievo dei Carracci: «Giostra di barriera a piedi» e «Giostra di campo aperto a cavallo») di patrizi bolognesi, italiani e stranieri (anche un inglese e un polacco) partecipanti alle due giostre tenutesi nel 1620 e nel 1628, nelle odierne piazza Maggiore e piazza Galvani.

Tarchiani, Gabrieli, Damerini. ACCADEMIA; Enciclopedia Italiana (1929). Treccani.it.

La R. Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna deriva direttamente dall'Accademia Clementina, nel 1709 approvata e onorata del suo nome da Clemente XI. Per quanto L. Sabbatini, L. Carracci, G. Reni avessero inutilmente tentato di costituire una vera e propria accademia riconosciuta e sussidiata dal governo, si erano avute in Bologna soltanto scuole private con tal nome, quali, ad esempio, la celebre Accademia degl'Incamminati, fondata dai Carracci, quella istituita dal conte Ettore Ghisilieri e ch'ebbe a maestri il Tiarini, l'Albani e il Guercino, e l'altra creata dal senatore Francesco Ghisilieri e diretta dal Malvasia e dal Pasinelli.

Chidester, Michael. Guido Antonio di Luca. Wiktenauer.com

He is known to have written a fencing manual around the turn of the 16th century, which has since been lost. The anonymous Bolognese MSS Ravenna M-345/M-346 have been equated with this lost treatise by Rubboli and Cesari, but the attribution remains unconfirmed.

Ghisiliero Chapter list: Link

Introduction

Theory