The Dark Arts of Bologna

Necromancy in Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Bologna

Necromancy or Necromantia, defined in its late medieval and Renaissance form, is the act of summoning or invoking a demon or spirit to do one’s bidding. The common belief was that because Christ could command demons, so too could his followers. Thus, passages like Mark 1: 21-281, Matthew 8: 28-342, and Luke 10: 17-203 empowered Christians with an untapped or underutilized authority over otherworldly spirits. Many of these rites had to be conducted in Latin, and were therefore predominately performed by clergy or educated elites.4 Of course, the reasons for performing Necromantia varied—discovering hidden treasures, obtaining sexual favors, performing illusions, healing grave illnesses, or even obtaining supernatural powers.5 6

Rituals were begun by tracing circles on the ground. Objects, shapes, symbols and letters were then drawn or placed about the circle.1 The Heptameron (ca. 1600), which may have been a grimoire composed by Cornelius Agrippa as an anonymous fourth installment in his collection2, Three Books of Occult Philosophy, explains the purpose of summoning circles, stating, “…the greatest power is attributed to the Circles; (for they are a form of defence to make the operator safe from the evil spirits)…"(di Abano; Heptameron, pg. 2). He explains how the circles are used in the following chapter:3

THE FORM of Circles is not always constant, but is to be changed according to the order of the Spirits that are to be called, their places, times, days and hours. For in making a Circle, it ought to be considered in what season of the year, what day, and what hour it is to be done; what Spirits you would call, to what Star and Region they belong, and what function they have. Therefore let there be made three circles nine feet across,* a hand’s breadth apart: in the middle circle write first the name of the hour wherein you do the work; second, write the name of the Angel of the hour; in the third place, the Sigil of the Angel; fourthly, the name of the Angel that rules the day when you do the work, and his Ministers.† In the fifth place, the name of the present season. Sixthly, the name of the Spirits ruling in that part of time, and their Presidents.‡ Seventh, the name of the head of the sign ruling in the season when you work. Eighth, the name of the earth according to the season; ninth, completing the middle circle, the names of the sun and moon according to the rule of seasons; for as the seasons change, so are the names to be changed. In the outermost circle, let there be drawn in the four angles the names of the presiding Angels of the air for that day wherein you work: to wit, the name of the King and his three ministers.§ Let pentagrams be made in the four corners,** outside the circle. In the inner circle, let there be written four divine names with Crosses interposed. In the middle of the circle, towards the East, let Alpha be written, and towards the west let there be written Omega, and let a cross divide the middle of the circle. When the circle is thus finished, you proceed according to the rules written below.

—(di Albano; Heptameron, pg.3)

The practice of necromancy naturally drew the attention of the ecclesiastic inquisitors when practitioners were discovered or accused of performing forbidden rituals. The story of inquisitorial persecution in Bologna is a particularly turbulent one. It dates back to the late 13th century—due to a collective of Cathars in the city of Bologna—before rearing its ugly head once again in the 14th century, this time due to the presence of Dolcinian heretics. While the Cathar and Dolcinian heresies had more to do with an asymmetrical reimagining of the Catholic faith than an illicit use of magic, their persecution at the hands of the church left many Bolognese citizens weary of any inquisitorial presence in the city. To belay this heightened sense of suspicion, the church started to designate a local priest to assume the role of Inquisitor.

Consequentially, in the mid-15th century, the combined factors of clerical representation often being a necessity to perform necromantic rituals and the general distrust of the church’s inquisitorial arbiters due to past injustices turned what would classically be characterized as a case of good vs. evil into a far more complicated matter when the occult became widely popular. The influence of this foray into the dark arts would extend well beyond the cultural milieu, and bury its hooks deep into the fabric of Bolognese history—including its fencing history.

Let’s take a closer look!

1444: Marco Mattei del Gesso

The first warning signs of this emerging fad appeared at the University of Bologna in 1444. Marco Mattei del Gesso, who was perhaps a child or relative of Sir Silvestro di Adamo del Gesso aka ‘il Mazza’, a good friend and war-buddy of Galeazzo Marescotti (one of the leading figures in the Bentivoglio faction), was discovered invoking demons with the priest Jacopo di Viterbo.

The inquisitorial investigation was performed by the Dominican scholar and university professor Gaspare Sighicelli, a native of San Giovanni in Persiceto and close friend of the future Pope Nicolas V. He found both parties guilty, after they later confessed and repented, but he let them both off with light penances.

1451: Nicolò di Verona

Now, to really understand the depth of this next nefarious necromantic episode we need to briefly examine the life of Achille Malvezzi.

Born in 1413, to Gasparo di Musotto Malvezzi and Giovanna Bentivoglio, Achille’s youthful enterprises largely remain a mystery. His brother Ludovico accompanied Annibale Bentivoglio in the service of the condottiere captain Micheletto Attendolo during his Neapolitan campaign on behalf of Renato d’Angiò against Alfonso of Aragon between 1436-1439, and the likelihood that Achille was also a part of the aforementioned retinue is fairly high.

After his return to Bologna alongside Annibale Bentivoglio in 1438, Achille joined the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem of Malta, the famed Knights Hospitaller. By 1442 he had already assumed the rank of preceptor for the Commenda di Bologna, which was a combined organization of crusading orders in the city.

Achille was an important member of the Bentivogleschi faction, and was one of the closest allies of his cousin Annibale Bentivoglio. In 1442, when Francesco Piccinino took over the Bolognese government, he imprisoned Achille and his father Gasapre alongside Annibale. Achille was sent to Castello Mompiano in Brescia.

During the chaotic years that followed his release, between 1443-1445, Achille played a key but quiet role, until Annibale’s murder at the hands of Betozzo Canetoli on the 24th of June 1445, which incited him to raise the Malvezzi banner alongside Galeazzo Marescotti, and their Bentivogleschi allies.

Following this, he took part in a number of defensive campaigns against the enemies of the Bentivogleschi faction: first against the Visconti, wherein he captured Monte Budello and Serravalle in 1445; then in 1449, where he conducted operations against the Venetian sponsored rebel forces led by the Pepoli, Fantuzzi, and Viggiani families that had occupied Castel San Pietro and other castles in the contado.

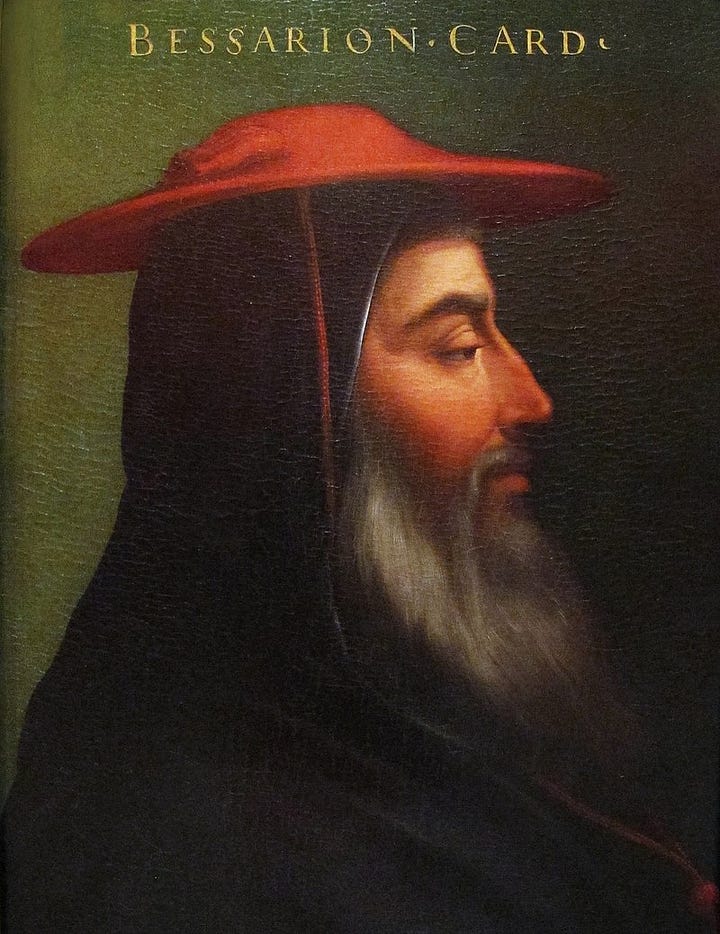

1451 saw an end to much of the violence. Sante Bentivoglio succeeded in defeating the rebel and Carpisian army that was threatening Bologna after they’d managed to break into the city through a smugglers port in the Reno Canal. Tangentially, Cardinal Bessarion, once established in the post of Papal Legate, was able to bring some much-needed diplomatic stability to the embattled Bentivogleschi regime. The now-peaceful landscape prompted a visit from the soon to be Holy Roman Emperor, Fredrick III, who was visiting Borso d’Este in Ferrara on his way to Rome, where he was set to receive papal confirmation of his titles. While in Bologna, he knighted the sons of Astorre Manfredi: Carlo (age 13), Galeotto (age 12), Giovanni II Bentivoglio (age 9), Pietro Antonio Pasello, Carlo Malvezzi, Christophoro Caccianemici, and Baldesserra Lupri. Then they feasted and the Regimento showed him the “spinning mills, which pleased him most of all, and he greatly praised the machinery” (Ghirardacci; Tutle, pg. 8)—this was Bologna’s top secret industrial backbone, fed by their sophisticated canal system.

Frederick III left for Rome, but briefly returned to Bologna after his coronation on the 9th of May, and departed the following day. Once Frederick was gone, Bologna suffered the most peculiar scandal. Sometime in June of 1452, don Nicolò da Verona, chaplain of the church of Fossola in Faenza, was arrested while passing through Bolognese territory. He was arrested by the Inquisitor Fra Corrado of Germany, and the Crocesegnati or members of the Society of the Cross4 (mostly composed of Dominican lay clergy). He was charged with invoking demons, misusing the sacraments, performing incantations, magic, and refusing to embrace the true path of the Christian religion. The priests defrocked don Nicolò and had the charges read before the podestà, who in turn condemned him to execution in the Piazza Maggiore.

The reason for don Nicolò da Verona’s presence in the city or the territory of Bologna is unstated, but given the timeline of events I suspect that Achille Malvezzi, the head of the Bolognese crusading order, hired him to heal his terminally ill father Gasparo di Musotto Malvezzi.

Here’s why …

When word of the verdict reached Achille Malvezzi, he dispatched a number of armed men to intercept the procession: Guglielmo da San Piero, Luca di Jacomo da San Giorgio, Lorenzo Brocho, Luca di Guglielmo the silk weaver, Nicolò di Robino, Antonio di Martino da Chola, Bartolomeo called Mangancino the barber, Nicolò da Remedia.

His well-armed cutthroats intercepted the procession at the Trebbo de’ Preti, the priests’ street, where they “forcefully” freed Nicolò from the hands of the court according to Ghirardacci. Then, they took the fugitive to the home of Achille Malvezzi and the Commenda di Bologna, where they gave him refuge. Malvezzi’s residence was the Manzione di Santa Maria del Tempio, or Mansion of St. Mary of the Temple, with its famed Knights Hall, built by the Knights Templar sometime in the 12th century. It was located between Via Corleone and Vicolo Malgrado, along the via Maggiore just inside the Porta Maggiore gate.

From the Manzione di Santa Maria del Tempio, they snuck Nicolò over to the aforementioned gate, and bribed the captain of the guard, Giovanni di Jacomo degli Angelellini, who let them through, whereupon they smuggled the enchanter down the Via Emilia to Imola, where he was able to get away safely.

Meanwhile, back in Bologna, word of the assault had reached the Podestà, who raised the general alarm and put the city on lockdown by having the bells of the towers rung. While his birri (deputies) roamed the city looking for the culprits, he went to the Legate, Cardinal Bassarion, to express his frustration over what had just transpired. Bessarion was infuriated and rebuked the lords of the Anziani, suspecting their involvement: “If cities are governed in this manner, you remain in the palace and govern Bologna as you see fit."

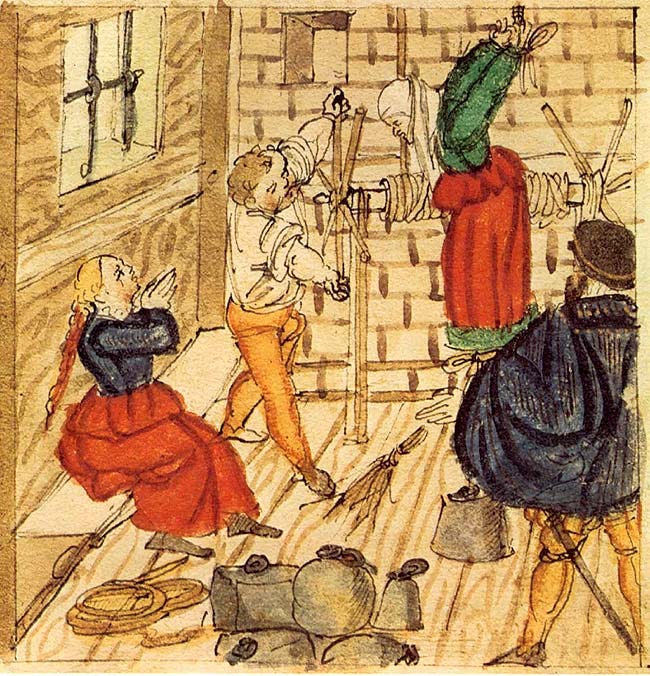

The Anziani were not informed of this matter, nor were they complicit in aiding Achille Malvezzi with any part of the escape. So when one of the culprits got picked up, the butcher Magantino (Antonio di Bisarino), and dragged before the members of the Regimento, they acted quickly and without reserve (i.e., they tortured him). Now, Magantino must’ve thought he was going to get off by pointing the finger at his accomplices because he told his interrogators exactly how they managed to escape the city. However, once they had the information they needed, they dragged Magantino into the Piazza Maggiore and hanged him without trial.

The reckoning didn’t stop there. They seized all of the possessions of Giovanni di Jacomo degli Angelellini, stripped him of his command, and burned all of his belongings publicly in the Piazza Maggiore. His accomplice Cesare della Bella dai Velli was declared a bandit, and the following were exiled:

Aldrovandi, son of Giovanni Malvezzo; Giovanni, son of Jacomo Angelelli; Giovanni, son of Bernardo dall'Amola; Luca, son of Jacomo da San Giorgio; Antonio, son of Martino dalla Cola; Luca, son of Guglielmo Bombasaro; Nicolò di Remulia; Cesare della Bella dai Velli; Gulielmo, son of Jacomo da San Piero; Lorenzo Broccho; and Nicolò di Rubino the mondatore.

As a result of this, Achille Malvezzi made some lasting enemies in the Dominican priory. Upon his death in 1468, the Dominican chronicler Girolamo Albertucci dei Borselli remembered Achille as a “defender of heretics who was also infamous for seducing nuns, several of whom bore him sons.” (Herzig, pg. 5 {1029}) This last was certainly true. Despite Achille’s vows of celibacy, he had two sons: Marc’Antonio and Guid’Antonio, known as Guiduzzo.

This isn't just a cool story. It has far-reaching implications, which will bear fruit as the narrative continues.

1465-1474: Antonio Cacciaguera

The case that really accelerated the late 15th century necromancy craze in Bologna was that of Antonio Cacciaguera. In 1465 the local inquisitor, Fra Girolamo Parlasca di Como, had just wrapped up a case against Fra Giovanni Faelli di Verona (what's with these Veronese priests!), who was accused of “invoking demons, profaning the sacraments, and casting harmful magical spells (maleficia).” (Herzig, pg. 5; 1029) The scholars at the University of Bolonga helped Parlasca shore up his prosecution so that he had a pretty open-and-shut case against Faelli, but Parlasca was lenient and let him off with light penance. The next case, though, Cacciaguera’s case, was highly unusual.

The Carmelite friar, in his first recorded confession, claimed to have had his seminal encounter with a demon when he was five years old, when the spirit granted him the power to cure epilepsy5. At the age of twelve, the demon made him enter an explicit pact in which he stomped on the cross and professed “I adore you as my god” before giving him the power to cure maladies. He was given the power to heal the sick (for profit—of course) by uttering the prayer, “in the name and reverence of the devil.”6

Cacciaguera was convicted of heresy, on the grounds that the act of invoking demons and entering into a pact with them was a form of devil worship, as per the Directorium inquisitorum, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment, but was eventually allowed to return to his priory under house arrest.

Both Fraelli and Cacciaguerra soon reverted to their old ways. In 1468 a new inquisitor took over the appointment in Bologna, one Fra Simone di Nicola da Novara. His first case was aimed at cracking down on the continued necromantic activities of Fra Giovanni Faelli, whom he charged with offering sacrifices to demons. It seems the good friar was running a brothel, which—Fra Simone claimed—his culprit had staffed with “demons in the shape of young women.” Fraelli was convicted and exiled.

The success of his prosecution of Faelli gave Fra Simone the confidence to go after Cacciaguera, who had also violated the terms of his commuted sentence by leaving his priory and profiting off of his demonically-gifted magical healing rituals once again. Simone’s case against Cacciaguera included charges of sortilegia (sorcery), maleficium (healing the bewitched), and performing spells from necromantic manuals, which he had obtained after his release along with his fellow Carmelite priests. Cacciaguera later confessed that he had indeed been performing necromantic rituals, wherein he and his fellow friars would “invoke demons by lighting candles, and then extract secrets from them with the aid of virgin boys”, who would act as pure incorruptible vessels for the demons to embody. (Herzig, pg. 10; 1034)

By all rights, Fra Simone could’ve turned Cacciaguera over to the Podestà of Bologna for execution, but instead, he let him off with life imprisonment in the Inquisition’s San Domenico prison (later commuted to a life sentence of house arrest in the Carmelite friary). That was, as long as he didn’t perform any of his priestly duties.

In 1473, Cacciaguera violated the terms of his release by celebrating Mass. A July investigation revealed that Antonio Cacciaguera and one Fra Giovanni Anguilla had, in the wake of his third conviction, been building up public support against the inquisitor, gathering a number of witnesses to attest to his innocence, among whom were, “two halter-makers, a butcher, a secondhand-clothes dealer, a messenger, a fisherman, one cloth cleaner, one artisan from Modena, the son a leather dealer, and sever other men identified only by name.”7

It wasn’t just a collective of local merchants and craftsmen that came to Cacciaguera’s aid, however. A Carmelite theologian by the name of Guglielmo Lepri of France8 stepped forward to defend the twice convicted necromancer. Guglielmo Lepri was the prior of San Martino and a graduate of the University of Bologna, where he earned a degree in theological studies in 1471 with the title master of theology which, in turn, had earned him a coveted seat in the collegium doctum (college of doctors). Rather than meet the Dominican inquisitors in the halls of divine justice, he went to the theological faculty of the University and started a debate.

The question Lepri posed to his fellow scholars was this: is the invocation and interrogation of demons a heretical act? Debate swirled, and earned Lepri an audience with papal Legate Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga and the jurist Michaele Barberio. They were convinced. On the 14th of June 1473, Cacciaguerra’s supplication was accepted and he was absolved of his sins on the grounds that the terms of his first case were void, and therefore he wasn’t a relapsed heretic. Fra Simone tried to get the pope to intervene in Cardinal’s Gonzaga’s decision, but nothing came of his protestations.

Fra Simone, for his efforts, was removed from his post and would never serve as an inquisitor again. In Bologna, the case against Cacciaguera would become something of a popular legend, and spawn a renaissance of demonic activity in the city.

Gentile Budrioli Rimieri 1498:

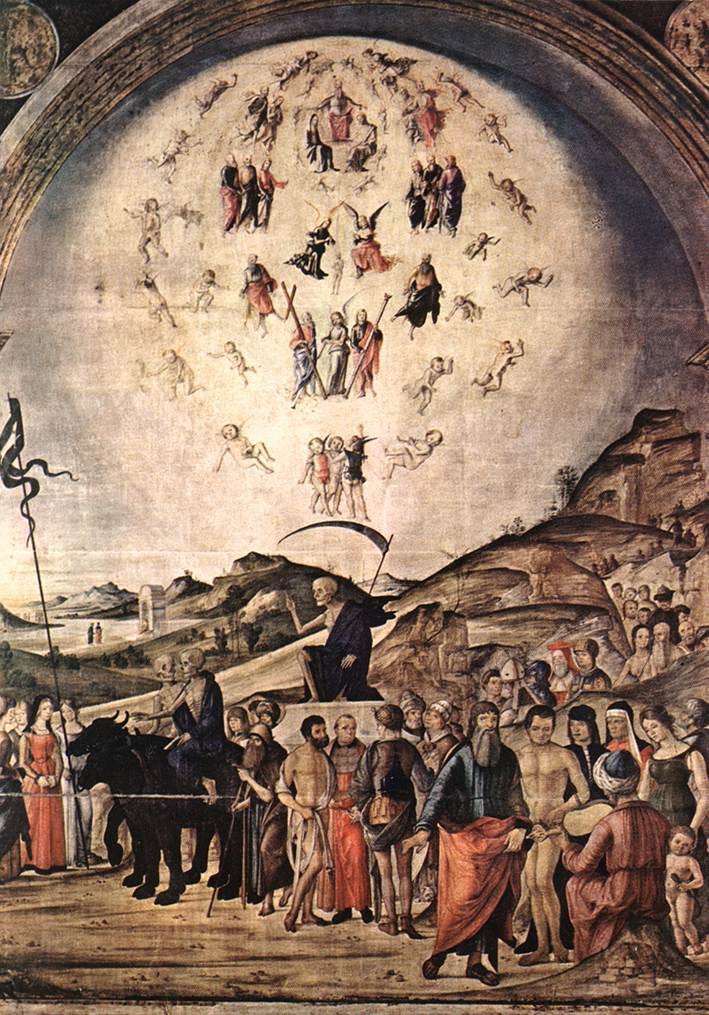

On the 14th of July 1498, after days of exhaustive torture and interrogation, Gentile Budrioli Rimieri confessed to being a witch, making a pact with the devil, and using her powers to enchant members of the Bentivoglio family. For these acts, she was burned at the stake. The full account of her testimony, as recorded by Cherubino Ghirardacci and Fileno dalla Tuata, is absolutely incredible. Not only does it further implicate the Malvezzi family, but it lets us in to a world of troubling dark secrets about the Bentivoglio family and provides some compelling context for the inclusion of Marozzo’s summoning circle in his 1536 Opera Nova.

Gentile was the daughter of Nicolò Budrioli, a wealthy Bolognese nobleman, who first appears in the Bolognese chronicles at Annibale II Bentivoglio’s wedding in 1484. As a young woman, Gentile was adventurous, curious, highly intelligent, and beautiful. She was a handful for her father, and as a consequence he was reportedly keen to arrange her marriage to the notari Antonio Rimieri—son of Carlo Rimieri, a doctor of law and professor at the University of Bologna—as soon as the match was proposed. She commanded a dowry of 500 ducats, and was treated to an immaculate wedding.

Gentile and Antonio had a fruitful union. By 1498 they had seven children: three girls and four boys. But the traditional role of matron never really suited nor satisfied Gentile; she wanted more out of life. Thus, early in their marriage, she started taking classes in medical astronomy at the University of Bologna, where she attended the lectures of the famed doctor Scipione, who introduced her to Tomasso Malvezzi and Tomasso Montecalvi, two charismatic noblemen and members of the Bolognese Regimento.

As Gentile delved deeper into her pursuits—and associated herself with high-status gentlemen outside of her husband’s usual social orbit—he started to get jealous, fearing that she would neglect her marital duties. He asked her to stop, and she did, but it didn’t take long for her to find a new refuge for her insatiable curiosity.

Antonio and Gentile owned a home in Torresotto di Porta Nuova, just across the street from the Basilica of San Francesco.9 It just so happened that one of her acquaintances from Scipione’s astronomy lectures was a friar at the Basilica, a man by the name of Fra Silvestro. He started teaching her about herbal remedies and healing potions (the Franciscans were the custodians of the healing arts among the ecclesiastical orders).10

Gentile was an exceptional student, meeting with Fra Silvestro almost daily, and quickly became a master of the Franciscan arts. Thus, the marriage of her medicinal astrological understanding to her newly acquired Franciscan herbal wisdom earned her a reputation as an exceptional healer. This didn’t sit well with her jealous husband Antonio, either. But, as fate would have it, Antonio wouldn’t have a say in her destiny. Thanks in large part to Gentile’s relationship with Tomasso Malvezzi and Tomasso Montecalvi, her skills came to the attention of Ginerva Sforza Bentivoglio, the first lady of Bologna, when she was having pains related to childbirth (she had 16 children).1112

Ginerva and Gentile became fast friends, sharing a deep fascination for the mysteries of esotericism, motherhood, and reading; and would spend countless evenings talking about their storied lives and shared interests. As a result, Gentile became a part of Ginerva’s retinue, and eventually a councilor in the Bentivoglio court. Together, they were a formidable duo, as both women were models of exceptional beauty, and could often be seen flaunting the latest fashions in the city: setting trends, turning heads. They were also very outspoken in the Bentivoglio court, by many accounts shaping much of the policy with strong opinions and a united resistance.

Ginerva came to care so much for Gentile that she provided a wedding dowry for one of Gentile’s daughters, and monastic dowries for two others. In kind, Gentile was able to heal a number of members of the Bentivoglio household—notably, Ginerva and Giovanni’s young grandson Sforza Bentivoglio (bastard son of Antongaleazzo), their daughters Laura Bentivoglio Gonzaga and Bianca Bentivoglio Rangoni; likely after childbrith.

As Gentile’s star began to rise, not all of the attention was approving.

Gentile’s ascent to power and prominence caught the eye of the Bentivoglio family’s political rivals and ambitious allies. They quickly seized on the opportunity to use her abilities as a way to tarnish the Bentivoglio reputation. Rumors started to swirl that Gentile had made a pact with the devil—that she was a witch.

Things got particularly nasty after she was able to heal young Sforza Bentivoglio. Allies of the now-exiled Malvezzi family quickly seized on the opportunity to influence connections in the Bentivoglio court, spreading rumors that Gentile was able to heal Sforza because she was the one who bewitched him in the first place. To further complicate matters, Giovanni II was reticent to put down these seditious machinations, because he was already under pressure from his allies due to implications that his court policy was being influenced by two ambitious women: Gentile and Ginerva.

Gentile was heartbroken when confronted with the rumors. According to the account compiled by Guidicini, “one night, while dozing over her books, she dreamt of five genuine witches who came to mock her. This dream, or rather nightmare, unfolds into a harrowing vision of a sabbath. The sabbath, which is expected to culminate in the appearance of Satan, ultimately concludes without incident due to Gentile's presence, as she is not a witch. The five witches express their disappointment, and as dawn approaches, they prepare to depart. Gentile implores them to reveal their names before leaving: they are prejudice, lies, ignorance, slander, and envy—these are the true witches that perpetuate evil in the world and reside within us. Gentile awakens from the dream, imbued with this newfound awareness.” (pg. 96)

Due to Giovanni II’s initial self-interest in letting the rumors propagate, he created an impossible situation that only had one feasible outcome. Pope Alexander VI was looking for a way to remove the Bentivoglio from power to cement his own Emilian-Romagnol dynasty, and Giovanni II’s enemies—especially in the Malvezzi family—were doing everything in their power to make sure the rumors spread. They injected new rumors into the Bentivoglio court that Gentile Budrioli was complicit in their conspiracy to murder Giovanni in 1488.

When confronted with this, Ginerva Sforza Bentivoglio pleaded with her husband to spare Gentile, to change the course of her best friend’s fate, but Giovanni II had no choice. In order to avoid further suspicion from the pope and preserve his seat of power, he had to turn Gentile over to the Inquisition.

Fra Giovanni Cagnazzo acted a chief Inquisitor in the investigation.

It’s worth taking a step back, and retelling the story from the perspective of Gentile’s confession as it was recorded by the contemporary sources.

Gentile Budrioli Rimieri opened her confession by stating that she had been practicing witchcraft and necromancy for 20 years. It started when she began attending lectures at the University of Bologna, where she studied astrology under Maestro Scipione, who was residing at the residence of Tomasso Malvezzi. From these two men, she came to know Tomasso Montecalvi and Fra Silvestro. Both Malvezzi and Montecalvi reportedly facilitated much of what happened next.

Fra Silvestro introduced Gentile to three other monks at the Basillica of San Francesco, who helped her refine her skills. Through their guidance she surrendered her soul and body to the devil, from whom she requested two favors: riches, and influence over powerful men. The devil replied that he could not give her riches, because he possessed none, but he could teach her how to bewitch people and then heal them, which would provide her both riches and influence. Upon sealing this pact she was able to command of over 72 demons, including Lucifer.

Her rituals and practice included the following. She would attend daily mass at the Franciscan Basilica where she would sit beneath the depiction of St. Michael with the devil beneath his feet, and mutter, “You lie in your throat” whenever the Gospel was read aloud. She would then light a candle beneath the image of St. Michael, not for the Archangel, but for the Devil beneath his feet, whom she worshiped. Three times a week, she would then don a chamisa, put on a mitre and a holy stole, and she would burn incense at an alter that she’d built from a {wood or copper} table, etched with the keys of Solomon, supported by four candelabras, with a candle burning at its center next to a figure of Lucifer, crowned, on his throne. When she was in need of supplies for her potions, spells, and powders, she would go into the graveyard of the Basilica, naked as the day she was born, and exhume the bodies so she could harvest their bones, organs, and tissue.

Gentile confessed to having bewitched over 400 people, including seven members of the Bentivoglio household, specifically Sforza Bentivoglio the bastard son of Alessandro Bentivoglio, Laura Bentivoglio, and Bianca Bentivoglio Rangoni (Guido II Rangoni’s mother). She also revealed that she was trying to bewitch Giovanni II Bentivoglio, and had she not been captured Bologna would’ve faced assured destruction.

While in prison, Gentile would often identify the Dominican monks who were coming to visit before they arrived, and could even provide them with details of what they were going to say, despite having no communication with the outside world. She later revealed to her jailors that long prior to her imprisonment she had acquired a spirit who would bestow her with divination and supernatural powers, like invisibility and fearlessness.

Fra Giovanni Cagnazzo and his Dominican brothers had heard enough. They sentenced Gentile Budrioli Rimieri to death, stating that no individual in over a millennium had practiced necromancy with such authenticity, and ordered that on the 14th of July, at 10am she should be tied to a stake in the courtyard of the Basilica of San Domenico and burned before noon.

Gentile’s confession came under the pressure of tremendous torture. She was subjected to the corda, and many who faced the perils of the Inquisition’s cruelty would confess to anything to be relived of the insufferable torment. So her confession needs to be taken with a considerable dose of skepticism.

However, the inquisitors were able to produce a number of the artifacts to corroborate her testimony, including her table, wares, and statue of Lucifer, as well as all of her powders, potions, and herbs. On top of this evidence, there were a number of witnesses that came forward to testify against her, including her husband, who claimed to have been bewitched by one of her bone powder concoctions, which made him confused and shrouded his ability to perceive her nefarious activity.

On the 14th of June 1498, in front of a crowd of thousands, Gentile Budrioli Rimieri fearlessly walked up the scaffolding erected in front of the Piazza San Domenico. Heavy chains were placed around her neck and cloths covered in tar draped over her body.13 The Dominican friars tied her to a stake at the center of the platform, and sometime between 11am and 12pm, the kindling beneath her feet was set alight.

As Gentile writhed in pain, and screamed for absolution, one of the friars cast a handful of gunpowder into the fire, which caused an explosion of flames, and terrified the crowd in attendance. They were convinced that it was the devil leaving her body, and many fled.

Not far from the proceedings, in the solitude of Gentile’s studio, Ginerva Sforza Bentivoglio is said to have watched the tragedy unfold from the window of the tower of Porta Nuovo, where she wept for her dear friend Gentile. She had begged for mercy, pleaded with Giovanni to spare her life, but when he explained the political implications to her, the reality of the situation at hand, that it was Gentile's life or their position in power—she relented.

Just weeks after Gentile's death, her son Carlo was also arrested and sentenced to 15 years in prison for heresy, necromancy, and divination.

Conclusion:

Let's talk about our cast of characters for a moment. It all starts with maestro Scipione. Many modern esotericists, I believe, conflate Scipione with Girolamo Manfredi or Hieronimus de Manfredis, giving him the name Scipione Manfredi. But in Ghirardacci and Fileno Dalla Tuata, he's remembered only as Scipione. In the registers of doctors and professors at the University of Bologna, there is only one prospective Manfredi whose timeline, academic career, and subject of study aligns with our mysterious Scipione, and that is the aforementioned Girolamo.

Now, if our suspect Scipione is Girolamo Manfredi, we have a bit of tale to tell. He attended the Universities of Bologna, Ferrara and Parma, graduating with a degree in philosophy and medicine in 1455. He started his academic career lecturing in logic, before switching to philosophy, and eventually medicine in 1465. In 1469 he took over the astronomy department and lectured in both subjects for two years before taking a break from astronomy until 1474, when he started teaching both subjects again. He continued in this role until his death in 1492. Notably, Manfredi was renowned for his expertise in medical science and catarchic astrology, driving the field with his understanding of how the movement of celestial bodies influenced individuals, regions and kingdoms.14 This is likely the reason that people make this connection. He was also a member of minor monastic orders, and had a tonsure to show his devotion.

Here’s the fun part. From whom did Mandfredi develop his commanding grasp of astrology during his early stint at the University of Bologna? Well, it very likely that it could’ve been … Filippo Dardi!

Dardi was one of the principal instructors in astrology until his death in 1463.15 Wouldn’t that be something!

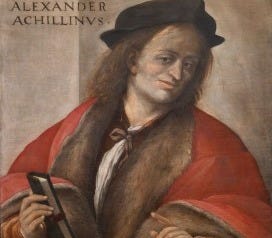

Gentile Budrioli Rimieri wouldn’t have been Manfredi’s only student known for dabbling in the occult either. His star student was Alessandro Achillini, who graduated from the University of Bologna with a degree in philosophy and medicine in 1484. From 1484-1495 Achillini taught philosophy at the University, and in 1495 he started teaching medicine. Achillini was fascinated with the occult, so much so that his students used to bandy the phrase, “aut diabolus aut Achillinus” {either the Devil, or Achillini} in regards to the origins of their lecturer’s eclectic esoteric rants. Alessandro was also a courtier of the Bentivoglio, and one can imagine that on a number of occasions at the Bentivoglio Palazzo he had cause to discuss matters of the supernatural with Gentile and Ginerva {Perhaps while a young Guido Rangoni listened in}.

Unfortunately, there is another prospective scholar and lecturer at the University that likely fits the character of Scipione, and that is Scipione da Mantova. He graduated from the University on the 27th of June 1487, and served as a professor of Astronomy from 1493 until 1497-98.16 Now, given Scipione da Mantova’s limited timeline, we don’t have a lot to work from, but that hard stop around 1497-98 kind of fits with the narrative. What doesn’t fit is his limited tenure. Perhaps it was just the inquisitors objective to get Gentile to confess that she had been performing necromancy for over 20 years—maybe to explain some weird occurrence (who knows), but it would seem rather odd for Gentile to begin her journey into the depths of the subject matter in a 4-5 year timeframe, and it wouldn’t really align with her political ascension or the Historiography of the story either.

A prospective counter narrative is that Girolamo Manfredi was the source of many of the leading esoteric lectures at the University, and it was in his lectures that Gentile came to meet our Scipione da Mantova, who introduced her to his social contacts Tomasso Malvezzi and Tomasso Montecalvi, who greatly encouraged Gentile in her descent. Manfredi continued to teach until his death in 1493, while prospectively, Scipione was removed from his position after he was implicated by the Inquisition in the Gentile scandal.

How about our two Tomasso’s? We have the most detail on Tomasso di Carlo Malvezzi Bentivoglio. The Bentivoglio at the end there was a late addition. In 1488 when the Malvezzi family tried to murder Giovanni II Bentivoglio, in a coup sponsored by il Magnifico, Lorenzo di Medici, where he famously advised the Malveschi adherents, “100 measures and 1 cut,” Tomasso managed to duck the purge, and changed his surname to Bentivoglio to avoid being associated with his now disgraced relatives.

Prior to the Malvezzi coup, in 1474, Tomasso was linked to another particularly heinous crime perpetuated by his brother Floriano. Just 28 years old at the time, Floriano was running a sophisticated counterfeiting operation in Bologna. When the operation started, his 25 man outfit would hammer the coin blanks outside the city, due to the noise, and then smuggle them in to the city so they could be pressed in the basement of a Goldsmith. The problem was, this was risky and highly inefficient, so they relocated their operation to the Malvezzi’s ancestral home in della Selva, between Bologna and Ferrara, in the abandoned Torre di Cavagli. At their height they had dies for producing Fiorentini, del Cavallotto di Ferrara, Ferrarese and Bolognese Quatrini—this was a big deal.

Then it all came crashing down. Giovanni Giacomo Gabrieli, one of the gang members, was buying some meat at a Bolognese butchers cart, and paid his bill with a counterfeit Fiorentini. The butcher recognized that it was a forgery and called the local birri, who arreested Gabrieli. The podestà’s interrogators threatened to put Gabrieli to the screws, and he spilled the beans on the full outfit, naming all 25 gang members and Floriano Malvezzi. The Regimento responded by putting an execution order out on the whole operation—except Floriano Malvezzi, he got off scot-free. Gabrielli, didn’t though. He hung himself in his prison cell to avoid the executioners axe. The incredible thing is, Floriano and Tomasso Malvezzi were never investigated for their role, as a matter of fact, Floriano was knighted by Giovanni II Bentivoglio in 1476. 17

Later, in 1505, when Giovanni II was in the heat of his feud with Pope Julius II, which would eventually lead to his removal from power in Bologna; both Tomasso Malvezzi and Tomasso Montecalvi would die from illness just weeks apart. Could Giovanni have been covering his tracks? Was their encouragement of Gentile part of a larger plot that Giovanni wanted to keep under wraps?

A part of me wants to believe that Giovanni II was running a big racket, where his cadre of necromancers would summon demons to find hidden treasure, buried by Floriano Malvezzi’s gang, inevitably swapping real coins for counterfeit ones. Lock Stock and Two Smokin’ Bombards. Or maybe he or Giverva were hashing a more sinister plot.

The occult connections don't stop there!

Gentile Budrioli Rimieri wasn’t the only family friend to get hit with charges of heresy in the late 15th century. Gabriele di Salò, another family friend and courtier was arrested by Fra Giovanni Cagnazzo da Taggia in 1497. He was sentenced to death, but this time the Bentivoglio went to bat for him, going as far as threatening the inquisitor, and this time they were able to secure his release with only light penances. Now, Gabriele’s crimes of heresy were more of your standard fare—denial of Christ’s divinity, the virginity of the Madonna, and questioning Christ’s miracles.18

Achillini, Salò, Burdioli, Malvezzi; we have to ask ourselves, what was going on in the Bentivoglio Palazzo? This was of course the fertile cauldron from whence young Conte Guido II Rangoni took his first steps while his mother was bewitched by Budrioli, and the curious stew that his dear friend—later in life—Achille Marozzo may have also been embroiled in at a young and impressionable age.

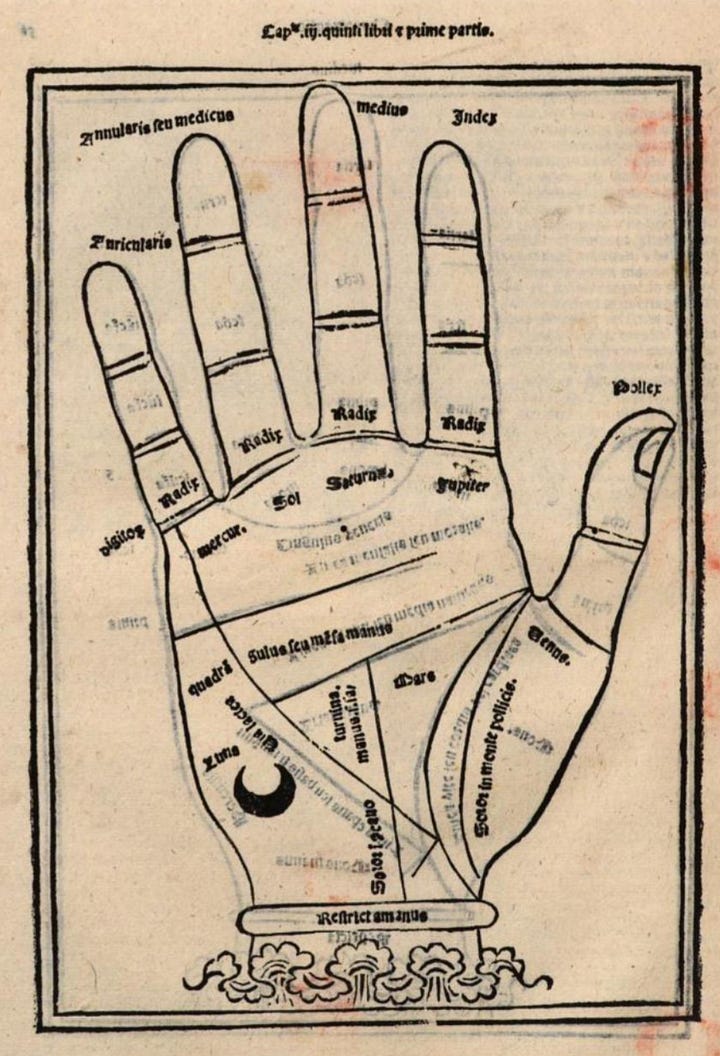

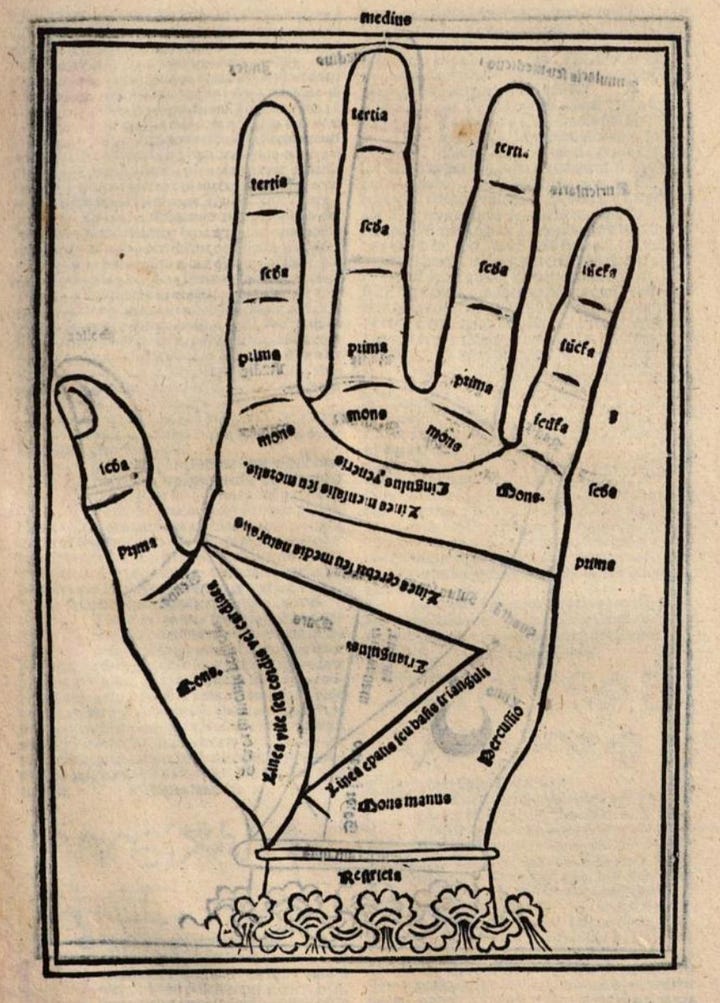

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Bentivoglio didn't shy away from their occult obsession, even after the Salò and Burdioli scandals. In 1504 Bartolomeo Rocca dedicated his, Bartholomei Coclitis Chyromantie ac physionomie anastasis : cum approbatio[n]e magistri Alexa[n]dri d[e] Achillinis, to Alessandro Bentivoglio. A work composed in conjunction with Alessandro Achillini, that features the palmistry divinations of Giovanni II Bentivoglio and Ginerva Sforza Bentivoglio.

If occult logic was being worked into every facet of discourse from medicine to philosophy, religion and rhetoric—then why not fencing?

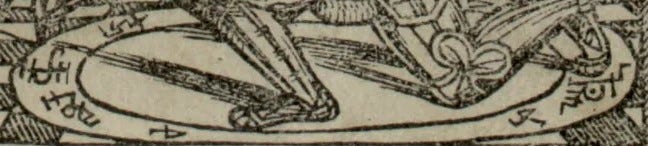

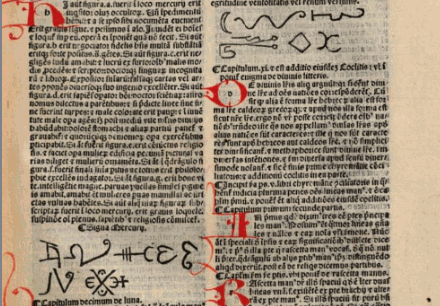

Of course Achille Marozzo styles himself in a summoning circle on the title page of his Opera Nova. The question is, why, and what does it say? I contacted a number of people to help me decipher his mysterious symbols, unfortunately they still remain a mystery, and might remain so for some time.

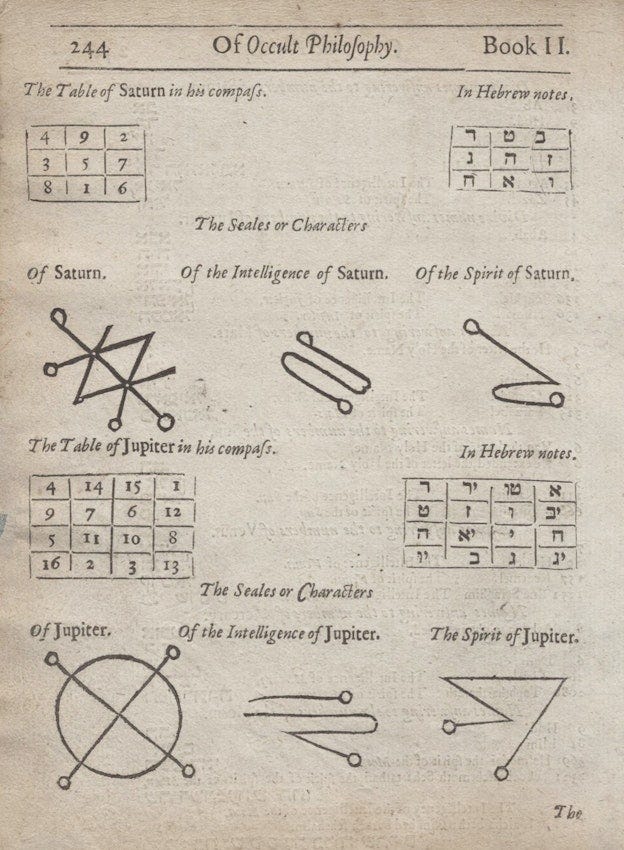

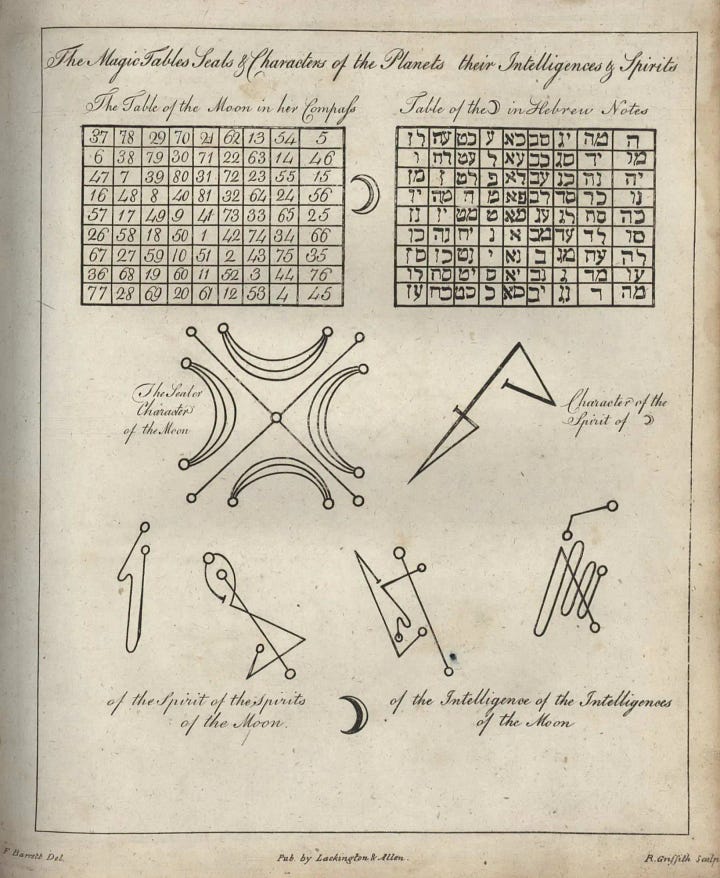

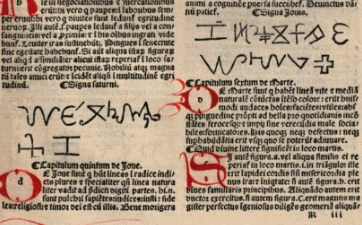

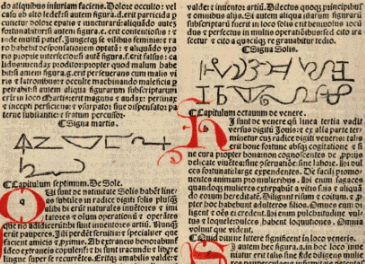

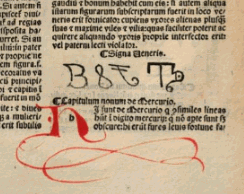

The inherent challenge, from what I can tell, is that many of the symbols were created based on a pattern of variables; day, time, planetary alignment, what spirit you were trying to conjure. They can get pretty complex, and it will take some work to decipher them. We do have some clues in the image outside of the symbols themselves, like the length and direction of Marozzo’s shadow, I think that’s a deliberate addition. Here’s an example of a few tables, and the the variety of symbols you can create from Cornelius Agrippa’s Three Books on Occult Philosophy:

Alas, our curious case of swords and sorcery doesn't end there. The great grandson of Galeazzo Marescotti and son of Ercole Marescotti, Emilio Marescotti was a student of Achille Marozzo’s. He was also a captain in Guido II Rangoni’s mercenary company roaming Spilamberto, southeast of Modena. In 1529 when he acted as padrino on behalf of Christoforo Guasco, both duelists had to give an oath that their swords were not poisoned or enchanted:

" Il padrin del Basco tolse una de le spade et immediate el potestà de la terra andò da l’Oria el solemnemente li dele sacramento che l’arme non fosseno atossicate over incantale, et cussi tulli se parlino del steccato,"

From the number of duels that we’ve looked at over the last few years, this is an exemplary case. Most duels don't have a record of the duelists swearing that their weapons are not enchanted. Of course, the padrino on the other side of the duel representing Niccoló Doria was Filippo Pepoli, the brother of Conte Ugo Pepoli, who fought a duel against Guido II Rangoni in 1516. They were longstanding political rivals of the Bentivoglio and the Bentivogleschi faction, and they would've been well aware of the salacious rumors swirling around the family and their allies.

So what can we take away from this?

The Bentivoglio’s haunting obsessions with necromancy and the occult had serious implications in their downfall, even if their involvement was at times just a convenient weapon wielded by their ever ambitious enemies. It’s worth noting, that many scholars have chastised the treatment of Ginerva Sforza Bentivoglio’s esoteric underpinnings as an unfair assessment of her character. However, it's highly unusual that so many occurrences of necromancy, heresy, and occult behavior surround the family and their allies through the mid-15th century, until their collapse in 1506, and beyond. It certainly wasn't a coincidence.

From Marco Mattei del Gesso, to Niccoló di Verona, Gentile Budrioli Rimieri, Gabriele di Salò, Alessandro Achillini, Bartolomeo Rocca, and Achille Marozzo the case of the Bentivoglio and the dark arts paints a fairly sorted narrative. There was something sinister hidden beneath the blasé façade of the later Bentivoglio Signoria, and it's dark tendrils are intricately woven into the very arts we practice today.

Maybe the next time you crack open Marozzo you'll remember, the devil is in the details.

Primary Source Translations:

Fileno dalla Tuata’s Take on Nicolò di Verona19:

"In June, the inquisitor of San Domenico arrested Don Nicolò from Verona, a priest who was residing in Fosella. He was an enchanter of devils and a master of many wicked deeds. They defrocked him and handed him over to the podestà, and he was sentenced by him. As he was being sent to the marketplace {piazza?} for justice, he was taken away by the following men:

Zoane of the Anzeleli, Guglielmo from San Piero, Lucha from San Zorzo, Lorenzo Brocho, Lucha the silk weaver, Nicolò of Robino, Antonio of Martin from the Chola, Bartolomeo called Mangancino the barber, Nicolò from Remedia, Cesare from Bella of the Vili.

They took the said priest and brought him to the house of Messer Achille Malvezzi at the Masson. The podestà and the inquisitor left the palace and went to the bishop’s residence. In order to calm the situation, they quickly seized Bartolomeo, called Mangancino, and without reading any sentence or confession, he was immediately hanged at the podestà’s gallows. The priest was sent to Imola."

(Translation by Stephen Fratus)

This is Ghirardacci's take on Nicolò di Verona20:

“The most holy Inquisition apprehends Don Nicolò of Verona, chaplain of the church of Fossola in the Bologna territory, accusing him of being a magician and enchanter. Refusing to embrace the true path of the Christian faith, he is handed over to the podestà and sentenced to death. As he is being led to execution and reaches trebbo de' Preti, armed young men intervene, forcibly rescuing him from the court's grasp and sending him outside the gate of Strà Maggiore.

The podestà, initially perplexed by the situation, rings the bell to prevent anyone from leaving the city. He then departs the palace to confront the legate, renouncing his authority, stating that he cannot uphold justice. The legate, infuriated by the crime, expresses a desire to visit the bishopric, addressing the lords of Anziani with the remark, "If cities are governed in this manner, you remain in the palace and govern Bologna as you see fit."

However, the lords of Anziani did not permit his departure; instead, they set out to pursue the criminals. Antonio di Bisarino, a butcher known as Magantino, is apprehended and confesses the names of his accomplices one by one. The senate seizes all possessions belonging to Giovanni di Jacomo degli Angelellini, which are then taken to the square and burned. Subsequently, he is stripped of his captaincy at the gate of Strà Maggiore, and Cesare della Bella dai Velli is declared a bandit by trumpet announcement for allowing the magician priest to escape.

The remaining guilty parties flee the city. The podestà, reinstated at the senate's request and tasked with continuing his duties and administering justice, has Magantino hanged without further trial. The following individuals are subsequently banished: Aldrovandi, son of Giovanni Malvezzo; Giovanni, son of Jacomo Angelelli; Giovanni, son of Bernardo dall'Amola; Luca, son of Jacomo da San Giorgio; Antonio, son of Martino dalla Cola; Luca, son of Guglielmo Bombasaro; Nicolò di Remulia; Cesare della Bella dai Velli; Gulielmo, son of Jacomo da San Piero; Lorenzo Broccho; and Nicolò di Rubino the mondatore.”

(Digital Translation)

Ghirardacci’s Account of Gentile Budrioli Cimieri 149921:

The spouse of Alessandro Rinieri was executed by fire in the town square, accused of being a formidable enchantress who had made pacts with the devil. The disturbing discoveries made in her residence were so unsettling that I hesitate to recount them, feeling a sense of dread. In essence, she had a level of intimacy with the devil akin to that of a cherished friend, who was exceedingly compliant in all matters. She was responsible for the downfall of Sforza, the son of Giovanni Bentivoglio, and when summoned to heal him—due to her reputation for curing the ill—her success ultimately led to her exposure as a malevolent sorceress.

This nefarious individual was named Gentile, the daughter of Nicolò Budrioli; she entered marriage with a dowry of 500 gold ducats and a splendid wedding. Upon her arrest, she confessed to having bewitched and harmed countless individuals, resulting in numerous deaths, particularly within the Bentivoglio household; she had also cursed a bastard son of Alessandro Bentivoglio, and she even attempted to ruin Giovanni Bentivoglio. She admitted to practicing this dark art for over 20 years, having been instructed by four friars of San Francesco and a master named Scipione, who resided in Galliera at the home of Tommaso Malvezzi, a faction member of the Bentivogli, along with friar Silvestro, who lived at the residence of Tommaso di Montecalvo. These two Tommasi bore significant responsibility for her actions, despite both holding positions within the regimento (Sedici), and had they not been apprehended, Bologna would have faced ruin and destruction.

She confessed to commanding 72 devils, particularly Lucifer, and recounted how she would often visit the churchyard of San Francesco at night, naked as the day she was born, to remove heads and limbs from corpses for her spells. She acknowledged having surrendered her soul and body to the devil, requesting two favors: the acquisition of treasures and favor with powerful masters and lords. The devil informed her that he could not provide treasures, as he possessed none, but he would teach her how to ruin individuals and subsequently heal them; he advised her to charge well for her services and to associate with influential masters to gain their favor. She discovered a copper table inscribed with various characters, supported by four candlesticks meant for candles; at its center sat a carved figure of Lucifer on a throne, crowned. Three times a week, she donned a shirt, a mitre, and a sacred stole, kneeling before the devil, offering incense with a thurible, and acknowledging him as the true deity.

Daily, she attended mass at San Francesco, holding the office in her hand; when the priest recited the Gospel, she would declare, “You lie in your throat.” She would then position herself behind the choir, where Saint Michael is depicted, with the devil beneath her feet, pretending to attach candles to Saint Michael while actually fastening them to the devil. Additionally, she wore a yellow cape adorned with two devils and possessed twelve olive sticks resembling dogwood, along with other sacred sticks, and a sword inscribed with sacred texts. She kept twelve bags filled with powders made from human body parts; when she intended to harm someone, she would touch them with the powder corresponding to the afflicted body part.

She also confessed to having a familiar spirit that remained with her until her death, demonstrating many signs of its presence in prison and at Saint Dominic; she would inform the inquisitor and others, “Now comes such and such a man, now comes such and such a woman to ask such and such a thing,” and soon after, the individuals would arrive, seeking what she had predicted. She admitted that all she needed was to have certain characters consecrated to gain invisibility, which would free her from fear of anyone in the world. It was concluded that for a millennium, no individual had practiced necromancy as authentically as she had; consequently, all the canonists convened at San Petronio, and she was sentenced to be burned on July 14th between 10 and 12.

On that Saturday, she was taken to the center of the square, where she was secured to a large post with chains around her neck and cloths of pegola draped over her. She ascended the scaffold with such boldness and without any fear that it was hard for anyone to believe, and there she was burned alive; she might have escaped had she not confessed to so many heinous acts, for Ginevra, the wife of Giovanni Bentivoglio, held her in great affection, having helped marry one of her daughters and placed two more of her daughters in the nuns of San Mattia. This was the favor she had earned. She resided in the tower of San Francesco.

(Digital Translation)

Fileno dalla Tuata’s Account of Gentile Budrioli Cimieri 149922:

Gentile, the wife of Ser Alessandro di Cimieri and the daughter of Nicholo Budriolo, who possessed a dowry of five hundred ducats of gold, was apprehended and confessed to having harmed and bewitched countless individuals, leading to many deaths. Notably, in the Bentivogli household, she caused the downfall of seven individuals, including a legitimate son of M. Alessandro de Bentivogli and one illegitimate child, both over seven years old. She claimed to have instructed four friars of San Francesco, a master named Sipion residing in the house, and Tomasse Malvezzi, a member of the Bentivogli family, along with his brother Zelvestro, who was associated with M. Tomasse da Montechalvo. These two Thomases were known for their charisma, despite having fallen from the office of Sedeces.

She confessed to having influenced more than four hundred people, asserting that had she not been captured, Bologna would have faced destruction. She admitted to having seventy-two devils under her command, particularly Lucifer. On several occasions, she attended the feast of San Francesco in a state of undress, as if born to sever the heads and limbs of the deceased for the purpose of casting spells. She acknowledged having surrendered her soul and body to the devil, requesting two favors: one for treasure and another for favor with esteemed masters and teachers. The devil responded that he could not grant these requests as he possessed none, but suggested that she could ruin people and subsequently heal them, thus ensuring her own reward from great masters and the pursuit of grace.

She discovered a wooden table adorned with numerous paintings of Solomon, featuring four chandeliers designed to hold candles. At the center sat a carved figure of Lucifer in a chariot, crowned. Three times a week, she donned a chamisa, a mitre, and a holy stole, presenting incense to the devil while acknowledging him as the true God. Each day, she attended mass at San Francesco, and when the priest recited the Gospel, she would exclaim, "You lie by the throat." She would then proceed behind the church where San Michele was depicted, with the devil beneath his feet, holding a candle for San Michele while also offering it to the devil. She possessed a sword inscribed with sacred engravings and carried twelve bags filled with various dust from different human body parts. When she intended to harm someone, she would take dust from the corresponding body part.

Additionally, she confessed to having a familiar spirit that remained with her until her death, revealing many signs about individuals in San Domenegho, predicting their arrival and requests. She sought certain items that would allow her to consecrate specific charters, which would render her invisible and instill fearlessness in her. Consequently, she concluded that no one in Milan possessed greater necromancy than she did, prompting all the chanters to gather in San Piero, leading to her sentencing to be burned at the stake.

On July 14th, between 11 and 12 o'clock on a Saturday in the middle of the month, she was taken to Saint Dominic's house and confined in a cell adorned with numerous lanterns and bread, where she was subjected to such frankincense that no one would think of her. Ultimately, she was burned alive until nothing remained.

(Digital Translation)

Bartolomeo Rocca and Alessandro Achillini’s Palmistry Book: Link

Catalogue of Symbols:

Works Cited:

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital.

Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna*.” Renaissance Quarterly 64.4 (2011): 1025–1058. Web.

A Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Bologna. Netherlands, Brill, 2017.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Print. Pg. 181-183.

Wikipedia contributors. “Munich Manual of Demonic Magic.” Wikipedia, 6 Aug. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munich_Manual_of_Demonic_Magic.

DI ABANO, PETER. HEPTAMERON OR ELEMENTS OF MAGICK. Edited by Frater T.S., Translated by ROBERT TURNER esq., 2002, nekropolis.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/heptameron.pdf.

Tamba, Georgio. MALVEZZI, Achille; Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 68 (2007). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/achille-malvezzi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 05/01/2024

Wikipedia contributors. “Necromancy.” Wikipedia, 5 Oct. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Necromancy.

Tuttle, Richard James. “Water Systems in Renaissance Bologna.” unibo.it, Università di Bologna, 2008, acrobat.adobe.com/link/review?uri=urn%3Aaaid%3Ascds%3AUS%3Abaae4af5-004f-334c-83e7-fe6bb20a2e33.

The Knight Templars in Bologna. www.cavazza.it/drupal/en/node/1101.

Venturi, Luciano Baffioni. “STORIE DEGLI SFORZA PESARESI.” www.academia.edu, July 2017, www.academia.edu/33964195/STORIE_DEGLI_SFORZA_PESARESI.

Wikipedia contributors. “Gentile Budrioli.” Wikipedia, 6 Oct. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentile_Budrioli#cite_note-:12-6.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Le Cose Notabili; “Porta Nova”. Origine Di Bologna, 4 Aug. 2018, www.originebologna.com/strade/porta-nova.

Redazione. Gabriele Da Salò - ERETICOPEDIA. www.ereticopedia.org/gabriele-da-salo. 2020. Digital.

Golinelli, Giorgio. Molinella; del suo passato Millenario. 2023. Digital. LINK

Cocles, Bartolommeo della Rocca. Chyromantie ac physionomie Anastasis: cum approbatione magistri Alexandri de Achillinis. N.p., per Hieronymum de Benedictis, 1517.

Wikipedia contributors. “Necromancy.” Wikipedia, 5 Oct. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Necromancy.

Circles were usually traced on the ground, though cloth and parchment were sometimes used. Various objects, shapes, symbols, and letters may be drawn or placed within that represent a mixture of Christian and occult ideas. Circles were usually believed to empower and protect what was contained within, including protecting the necromancer from the conjured demons.

DI ABANO, PETER. HEPTAMERON OR ELEMENTS OF MAGICK. Edited by Frater T.S., Translated by ROBERT TURNER esq., 2002

This short grimoire was first published in the late 16th century, bound up with De Occulta Philosophia, seu de cæremoniis Magicis – the spurious “Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy” attributed to Agrippa – and was reprinted with it as part of a collection of supplementary material to Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy in an undated (ca. 1600) edition of Agrippa’s Opera.

https://nekropolis.dk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/heptameron.pdf

In case you want to read the full translation, and dabble in some necromantic rituals.

Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna*.” Renaissance Quarterly 64.4 (2011): pg. 1027.

From 1451, inquisitors in Bologna also relied on the Crocesegnati (Society of the Cross), a confraternity of lay auxiliaries who were supposed to assist them in carrying out their inquisitorial duties.

Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna*.” Renaissance Quarterly 64.4 (2011): 1025–1058. Web.

As noted in one of the legal opinions, during his first trial Caciaguerra confessed that when he was about five years old, he was ‘‘taught by a demon who appeared to him in the shape of an old man’’ how to cure epilepsy.

Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna*.” Renaissance Quarterly 64.4 (2011): 1025–1058. Web.

The Carmelite friar confessed that the demon in black had instructed him to enter an express pactum (pact) with him by asserting ‘‘I adore you as my god’’ and trampling he cross under his feet. According to Cacciaguerra, the demon had also taught him how to cure various maladies by means of fumigation. He thereafter earned money by healing the sick and the possessed by uttering prayers ‘‘in the name and in reverence of the devil.’’

Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna*.” Renaissance Quarterly 64.4 (2011): 1025–1058. Web.

When the Bolognese Filippo of Gambara was questioned by Simone of Novara, he confirmed that one of Cacciaguerra’s Carmelite friends, Fra Giovanni Anguilla, gathered a group of men who were willing ‘‘to say and do whatever they knew and could do for Fra Antonio, against the Office of the Inquisition.’’55 The group organized by Anguilla included three millers, two halter-makers, a butcher, a secondhand-clothes dealer, a messenger, a fisherman, one cloth-cleaner, one artisan from Modena, the son of a leather dealer, and several other men identified only by name. 56 The depositions that Fra Simone collected do not explain why these artisans and skilled laborers concerned themselves with the Carmelite friar’s case. It is unlikely that they had collaborated with Cacciaguerra in the pursuit of hidden riches, since this was a kind of activity typically reserved for clerical necromancers and their upper-class or upper-middle-class accomplices. The millers, halter-makers, butcher, and messenger who backed Cacciaguerra may have been personally acquainted with the Carmelite healer. Perhaps Cacciaguerra had assisted them in the past, in determining whether they or their relatives had been bewitched, in healing the sick, or in exorcising the possessed.

Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna*.” Renaissance Quarterly 64.4 (2011): 1025–1058. Web.

The Carmelite theologian Guglielmo Lepri of France (f l. 1464–79), prior of San Martino, was a key figure in the concerted efforts to facilitate the reversal of Cacciaguerra’s sentence.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Le Cose Notabili; “Porta Nova”. Origine Di Bologna, 4 Aug. 2018, www.originebologna.com/strade/porta-nova.

Nel 1498 era abitato da Gentile di Nicolò Budrioli moglie di Alessandro Cimierio Cimeri probabilmente figlio di Carlo dott. di legge e lettor pubblico di questa nostra Università, dotata di scudi 250 d‘ oro, la quale fu bruciata per stregaria li 14 luglio 1498.

Venturi, Luciano Baffioni. “STORIE DEGLI SFORZA PESARESI.” www.academia.edu, July 2017.

In preda allo sconforto, Gentile corre nel convento dell’amico e compagno di studi fra Silvestro e lo trova intento a elaborare alcuni preparati erboristici. I Francescani sono da sempre custodi dei segreti delle erbe officinali e il frate volentieri trasmette il suo sapere a Gentile, che ora conosce i misteri delle stelle e delle piante. Cerca quindi di convincere il marito a lasciarla proseguire negli studi perché vuole mettere a disposizione degli altri queste sue conoscenze. Il notaio continua a negarle la sua approvazione, ma ben presto si diffonde ugualmente la voce che Gentile ha facoltà di guarire i mali dell’anima e del corpo.

Venturi, Luciano Baffioni. “STORIE DEGLI SFORZA PESARESI.” www.academia.edu, July 2017.

Ginevra Sforza nel frattempo, pur essendo molto religiosa, è anche affascinata dall’esoterismo e dalla superstizione. Non appena la fama di Gentile giunge a lei, Ginevra vuole conoscerla, e le due donne diventano amiche.

Wikipedia contributors. “Gentile Budrioli.” Wikipedia, 6 Oct. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gentile_Budrioli#cite_note-:12-6.

Sforza first approached Budrioli due to having pains relating to childbirth.

Cloths of pegola

Florio Dictionary 1598: Pegola, pitch or tarre. Also an infectious whore.

Manfredi, Girolamo, son of Antonio Bolognese, graduated in Philosophy and Medicine in 1455. He attended a lecture in Logic, subsequently transitioning to Philosophy and then to Medicine in 1465, followed by a focus on Astronomy in 1469. He was tasked with compiling the __ino, which included a monthly description of the planets, their phases, and the optimal days for bloodletting and administering purgatives. He taught Astronomy alongside Medicine for two years before dedicating himself solely to Medicine for another two years. In 1474, he returned to Astronomy, which he taught with great acclaim until his death in Bologna in 1492. He was affiliated with the Colleges of the aforementioned faculties. Renowned for his expertise in Medical Science and judicial Astrology, he applied himself with remarkable diligence, achieving a level of proficiency unmatched by his contemporaries. During that era, a physician was not deemed competent unless he also possessed knowledge of Astrology and understood the influence of the planets on individuals, regions, and kingdoms.

Manfredi, Girolamo, figlio Antonio Bolognese, laureato in Filosofica e Medicina nell’ anno 1455, in attenne una Lettura di Logica, e quale passo alla Filosofica nel indi alla medica nel 1465, e l’Astronomica nell’ anno 1469, obbligo della compilazione del __ino consistente nella descrizione mensuale de’Pianeti, e delle loro fasi, e de’ giorni atti a levar saugue, ed a somministrar purganti. Coninuo ad insegnare l’Astronomia insieme alla Medicine per un biennio, dopo di che lascio l’insegnamento dell’Astronomia, e si diede a leggere seltanto la Medicina per due anni, ed in fine nel 1474 torno all’ Astronimia, che continuo ad insegnare con sommo grido sino al 1492 epoca di sua morte avvenuta in Bologna. Era ascritti ai Collegii delle predette facolta. Fu uomo rinomatissimo per la Scienza Medica, e per l’ Astrologia giudiciaria, alla quale s’ applico con tutta l’attivita del suo ingegno, per cui non vi fu alcuno che lo ugagliasse. A que’ giorni non era reputato valente Medico chi non possedeva anche l’Astrologia, e non sapeva l’influsso de’ PIaneti sopra degli uomini e delle Provincie e de’Regni.

Dardi Lippo, also known as Filippo, son of Bartolomeo Bolognese, served as a lecturer in Arithmetic and Geometry from 1443 through 1463. In 1444, he additionally taught Astronomy. Alidosi erroneously claims that Lippo's tenure ended in 1461; however, he is also recorded in the Rolls for the years 1462 and 1463. Furthermore, it appears that Alidosi mistakenly includes a Spanish Lippo Dardi among the Forentirri Doctors, who purportedly lectured in Arithmetic and Geometry from 1444 to 1453. The Rolls only document the aforementioned Dardi Bolognese, and the surname itself suggests a duplication, as we are unaware of any other individual by that name, contrary to several others who will be noted in due course.

2843.Scipione da Mantova, lauresto in Medicina nel nostro Studio li 27 Giugno 1487. Fu Professore di Astronomia dell’ anno 1493 per tutto il 1497-98.

2843. Scipione da Mantova graduated in Medicine from our University on 27 June 1487. He served as Professor of Astronomy from 1493 until the conclusion of the 1497-98 academic year.

Golinelli, Giorgio. Molinella; del suo passato Millenario. 2023. Digital. LINK

LA TORRE DEI CAVAGLI USATAG GUIDATA DA FLORIANO MALVEZZI

Nel 1474, accade un fatto grave che avrebbe potuto infangare l’onore della famiglia Malvezzi, un fatto di ordinaria ingiustizia dettata dalla Ragion di Stato. Floriano Malvezzi, di anni 28, figlio secondogenito di Carlo, primo conte della Selva, aveva organizzato una banda di 25 membri per la falsificazione di monete, con basi nella città di Bologna e provincia. Alcune lavorazioni non rumorose (come la fusione dei metalli), venivano svolte a Bologna presso la casa di un orefice e in una cantina mediante sofisticati torchi per ritagliare rapidamente i tondelli. Le lastre da cui ricavare i “tondelli”, dovendo essere assottigliate a martello, non potevano essere lavorate in città perché il fracasso provocato avrebbe generato sospetti. Quindi questa lavorazione fu portata all’interno della disabitata Torre o Rocca di Cavagli, una terra isolata posta nel feudo dei Malvezzi della Selva al confine tra il bolognese e il ferrarese. La zecca clandestina della Torre dei Cavalli inizia a fabbricare monete di ottima qualità estetica utilizzando diverse paia di conii; due paia servivano a coniare i “Grossi Fiorentini”, tre paia per i “Grossetti del Cavallotto di Ferrara” ed un numero imprecisato per i “Quattrini” bolognesi e ferraresi. Ma un giorno un tal Giovanni Giacomo Gabrieli, membro della banda, mentre stava acquistando carne a Bologna con 5 “grossi fiorentini” falsi, destò i sospetti del macellaio per cui fu scoperto e imprigionato. Per evitare torture (era la prassi del tempo) decide di confessare facendo il nome di Floriano Malvezzi, come principale organizzatore della banda, e di tutti gli altri compagni, nonostante avesse fatto giuramento, all’inizio di quella spericolata attività, di mantenere il segreto. Seguono condanne di morte in contumacia per i 25 membri della banda nel frattempo messisi al sicuro. Floriano Malvezzi non viene neppure inquisito essendo protetto dalla ragion di stato. Il povero Giacomo Gabrielli, per evitare la decapitazione, si suicida, impiccandosi, in carcere. Floriano Malvezzi non solo non viene punito ma due anni dopo, nel 1476, viene addirittura niminato cavaliere da Giovanni II° Bentivoglio.

Redazione. Gabriele Da Salò - ERETICOPEDIA. www.ereticopedia.org/gabriele-da-salo. 2020. Digital.

Gabriele da Salò è stato un medico eterodosso, perseguitato dall'Inquisizione di Bologna nel 1497.

Medico attivo a Bologna, negava la divinità di Cristo, l'origine divina dei suoi miracoli e la sua presenza reale nell'ostia consacrata, nonché la verginità della Madonna. Profetizzava inoltre l'imminente fine del cristianesimo. Per questo nel 1497 fu fatto arrestare e fu processato dall'Inquisitore Giovanni Cagnazzo da Taggia. Il processo contro di lui si concluse con la sua condanna a morte. Ma Gabriele di Salò si salvò grazie alla protezione della potente famiglia bolognese dei Bentivoglio che minacciò l'Inquisitore, che fu costretto a lasciarlo libero, imponendogli solo lievi penitenze.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print. Pg. 307-308.

De gugno lo inchixidore de San Domenego prese don Nicolò da Verona priete che steva a Fosella, ed era inchantatore de diavoli e maestro de molte robaldarie, el quale feçeno desgradare e dare al podestà, e da lui fu sentençiato e mandandolo al mercha' ala justiçia li fu tolto dalì infraschriti:

Zoane deli Anzeleli, Guglielmo da San Piero, Lucha da San Zorzo, Lorenço Brocho, Lucha banbaxaro, Nicholò de Robino, Antonio de Martin dala Chola, Bartolomeo dito Manghançin barbiero, Nicholò dela Remedia, çesaro dela Bella dai Vili,

Tolseno el dito priete e portonolo a chaxa de messer Achille Malveço ala Maxon, di che e' legato e 'l podestà se ne usirno de palaço e se n'andorno in veschoado e fu neçessario per aquedarli pigliorno Bartolomeo dito Magançino subito semça liegere chondanasone né confesione inchontinenti fu apichato ala renghiera del podestà, el priete andò a Imola.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. pg. 141.

“La santissima Inquisitione fa prigione don Nicolò veronese capellano della chiesa di Fossola , territorio di Bologna , per mago et incantatore , il quale non si volendo dare in braccio alla vera via della religione cristiana , è dato nelle mani del podestà et condannato alla morte . Et conducendolo al supplicio , et giungendo al passo del trebbo de ' Preti , se gli scuoprono addosso giovani armati , et a forza il tolgono dalle mani della corte et lo salvano man- dandolo fuori della porta di Strà Maggiore . Il podestà non sì tosto intende il fatto , che fa suonare la campana et non lascia uscir persona fuor della città ; poi si parte di palazzo et passa al legato et gli renuncia la bacchetta con dire che egli non puole esseguire la giustitia ; et il legato , adirato del fallo commesso , anch'egli vuol passare al vescovato, dicendo agli signori antiani , se a questa guisa si governano le città. " Voi restate in palazzo et a vostro" modo governate Bologna ,. Ma gli signori antiani non gli lasciarono partire ; anzi datisi a cercare i malfattori , fu trovato Antonio di Bisarino beccaro detto Magantino , il quale confessò li compagni ad uno ad uno . Et il senato, fatto pigliare tutte le robbe di Giovanni di Jacomo degl'Angellini, le fece portare in piazza et quivi abbrugiarle. Poi fu privato del capitanato della porta di Strà Maggiore Cesare della Bella dai Velli et gridato alla casa con la tromba per bandito per haver lasciato passare il prete mago. Il restante de' colpevoli tutti si fuggirno della città. Il podestà, ritornato a' prieghi del senato al luogo suo di prima, et pregato al seguitare il suo offitio et fare giustitia, egli senza altro processo fece impiccare Magantino. Poi furono banditi gl'infrascritti: Aldrovandino di Giovanni Malvezzo, Giovanni di Jacomo Angelelli, Giovanni di Bernardo dall'Amola, Luca di Jacomo da San Giorgio, Antonio di Martino dalla Cola, Luca di Guglielmo bombasaro, Nicolò di Remulia, Cesare della Bella dai Velli, Gulielmo di Jacomo da San Piero, Lorenzo Broccho, Nicolò di Rubino mondatore.”

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. Pg. 294-295.

È abbru giata nel mezzo della piazza la moglie di Alessandro Rinieri per esser grandissima incantatrice, la quale sagrificava al demonio. Furono trovate in casa sua cose si orri bili, che per me temo di scriverlo et mi spavento. Insomma ella haveva col demo nio tanta familiarità, come del più caro amico che potesse havere, et egli in tutte le cose era ubbi dientissimo. Ella guastò Sforza fanciullino, figliolo di Giovanni Bentivoglio, et essendo chia mata a curarlo, come quella che nome haveva di gu arire gli affaturati, et havendolo risanato, fu questa la cagione di farla scoprire per maga scelerata. Questa femmina malvagia aveva nome Gentile figlia di Nicolò Budrioli; ebbe ducati 500 d'oro in dote con nozze magnifiche al suo maritaggio. Fu p resa e confessò avere guasto et ammaliato infinite persone e fat tone morire assai, e massime in casa de' Bentivogli; e guastò un figlio ad Alessandro Bentivogli ed un bastardo, e più che voleva guastare Giovanni Bentivogli . E confessò aver fatto q uesto mestiere più di 20 anni, che gli era stato insegnato da 4 frati di San Francesco ed un maestro Scipione che stava in Galliera in casa di Tommaso Malvezzi fattore de' Bentivogli e fra Silvestro che stava in casa di Tommaso di Montecalvo. Quest i due Tommasi n'ebbero carico assai, benchè fossero tutti due dell'uffizio de '16 del reggimento, e se non era presa, era la rovina e la distruzione di Bologna. Confessò avere 72 diavoli a sua ob bedienza, e massime Lucifero, e di notte andò più vo lte nel sagrato di San Francesco nuda come nacque a togliere teste e membri a persone morte per far malie. Confessò aver data l'anima e il corpo suo al diavolo e dimandateli due grazie, l'una di aver tesori, l'altra di aver grazia con gran maestri e signori; il diavolo gli rispose non poterli dare tesori, perchè non ne aveva, ma ben gli insegnaria guastar persone e poi guarirle; e che ella si facesse ben pagare, e che s'impacciasse con gran maestri, che acquistaria grazia. Se gli trovò una tavo la di rame con molti caratteri di calamo, quale si drizzava su 4 candelieri, che avan zavano di sopra per mettere le candele; e in mezzo v'era Lucifero intagliato a sedere su una sedia colla corona in testa; e tre volte la settimana si metteva in d osso un camiciotto, una mitra in testa ed una stola al collo sagrata, e si metteva in ginocchio avanti al diavolo, e con il turribolo gli dava l'incenso e riconoscevalo per vero Dio. Poi andava ogni di in San Francesco a messa con l'uffizio in mano; e quando il sacerdote diceva l'evangelio, lei diceva: “Tu ti menti per la gola.” Poi andava dietro il coro, dove è san Michele , con il diavolo sotto i piedi, e fingeva attaccare le candele a san Michele e le attaccava al diavolo. Ancora si metteva su il camiciotto una mantellina gialla, dipinta con due diavoli. Aveva 12 bacchette d'oliva di color di sanguinello ed altre bacchette tutte sagrate, ed aveva una spada scritta e sacrata. Ed aveva dodici sacchette di diverse polveri di membri umani, quando voleva guastare una persona in un membro, toccava colla polvere di quel tal membro. Ancora confessò avere uno spirito familiare, quale non l'abbandonò sino alla morte, e mostronne molti segni in prigione ed in San Domenico ; e diceva all'inquisitore ed alle persone: "Ora viene il tal huomo, ora viene la tal donna a domandare tal cosa”; e stava poco a venire tal persona, e domandavali quanto aveva detto. E confessò che non gli mancava se non far consagrare certi caratteri , che avria avuta la invisibilità, che poi non avria avuta paura di persona del mondo. Di modo che si concl use che da mille anni in qua non fu uomo, nè donna, che avesse più vera negromanzia di questa; e per questo si raccolsero in San Petronio tutti i canonisti, e fu sentenziata al fuoco a dì 14 luglio a ore 10 in 12. Il sabbato in mezzo alla piazza fu condotta e quivi messa su un palio in una lumiera grande, legata con catene al collo, e a traverso con panni di pegola intorno a lei . Montò sul palco con tanta franchezza, e senza timore alcuno , che non è uomo, che lo credesse, e quivi fu abbruciat a viva tutta; e saria scampata, se non confessava tante ribalderie, perchè Ginevra moglie di Giovanni Bentivogli l'amava assai e gl'aveva maritata una figlia e mes sone due nelle suore di San Mattia del suo proprio; e questo era il merito che glie ne rendeva. Costei stava nel torresotto di San Francesco.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print. pg. 399-401.