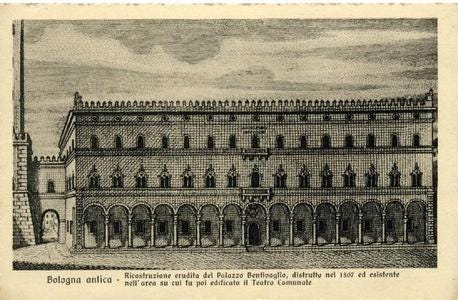

Snow covered the barren fields outside the city of Bologna, but inside the walls it appeared to be springtime: the city was covered with “greenery, cloths, garlands, fruits & flowers.”[1] This was especially true in the area around the great palazzo of the Bentivoglio, lords of the city. There was a wedding to be celebrated and the Bentivoglio had prepared an absolutely shameless demonstration of their wealth. The head of the family, Grandpa Bentivoglio, had broken open his strong boxes and called in every favor to welcome a new bride to the family.

In the words of the Bolognese historian Cherubino Ghiradacci this wedding was, “one of the biggest events in the history of Bologna,” a history that stretched back for two millenia.[2]

Little Guido Rangoni could not have cared less. He had been dragged from his comfortable home in the countryside where his days were filled with walking, running, crawling, finding sticks to swing and to chew on, and looking for animals to chase. He had been brought to the city, had been bathed and dressed in a doublet far too stiff and fine for a toddler. There he was kept in the company of his nurse, a woman who kept a tight, even painful hold on him inside the great palazzo.

The situation was going to get even worse for little Guido Rangoni. When his uncle Hannibal reached the walls of the city with his bride, a bevy of trumpeters blew lustily into their instruments. The call reverberated throughout Bologna, over the ordinary noises of a crowded city full of life. The trumpeters’ cry penetrated the walls of the palazzo. This meant little Guido now had to go outside, had to go wait in the cold and then, horror of all horrors, to stand still.

At the edge of the city, Hannibal Bentivoglio, the eighteen-year old scion of the Bentivoglio family led an entourage of 150 “richly-dressed” cavalrymen and four armored knights with lances standing upon their thighs. These formed a procession before his bride, Lucretia of the d’Este family. The lady herself was a sight to see, a sight to fill every maid in Bologna with envy. She had come to Bologna dressed in glittering golden brocade —a gown woven from silk and fine threads of gold.[3] Her dress alone was worth more than an ordinary man would make in twenty years of hard labor.

Ambassadors of all the great powers of Italy waited outside the walls of the city to congratulate the young couple. Among these was the most famous man in Italy at the time, the great Lorenzo di Medici, known as the Magnificent. He was the leader of Florence. It was a tremendous and surprising honor that he had come to Bologna in winter and attended the wedding personally. The other important men of Italy merely sent representatives.

But today was not about the lords, but about the bride.

After the greetings at the gate, young Lucretia starred in a parade through the city. The future Lady of Bologna needed to be seen by her people. So, surrounded by eight “splendid young men,” she followed a slow procession through the many gates of the city. This gave the citizens of Bologna a chance to see her and welcome her. At each of the gates the people of the city sang for her and performed little skits that extolled one of the seven cardinal virtues: hope, charity, temperance, justice, prudence, faith and fortitude.

Finally, to the roaring of cannons and the clamor of church bells, Lucretia came to the great Palace of the Bentivoglio family. Here little Guido Rangoni fidgeted in the firm grasp of his nurse. Grandma Bentivoglio was there with her daughters and the other leading ladies of Bologna, all dressed in lavish garments.[4]

Little Guido was introduced to Auntie Lucretia as the boy who would one day command the army of Bologna, once Uncle Hannibal became lord of the city. Then Lucretia moved on to meet Guido’s close cousin, Astorre, “the most beautiful boy in all of Italy.” Though this child’s short life would be full of terrible tragedy on this day the future seemed to hold nothing but sugar and rosewater for him and his relatives.

Family members were another crucial form of wealth in Renaissance Italy: every boy was a future warrior or cleric, every girl another chance to form a crucial alliance. In a cutthroat society like Renaissance Italy individual wishes had to take a back seat to survival. The Bentivoglio showed off their children to the ambassadors from throughout Italy as well as to the family of Lucretia. This was important to the Bentivoglio, because with all the eyes of Italy upon them, they needed to show that they were disciplined, united, and not only had a fortune, but enough family members to protect it. In other words a family on the rise. A family worth connecting to.

High society life in the Renaissance was equal parts King Arthur and The Godfather.

The Banquet

The first night of the wedding celebrations featured an extravagant feast for the most honored guests of the weddings. The first delight was a castle made of sugar, from which birds burst through, to the enjoyment of the company.

Then there were the usual foods you would expect. But for the great lords there were was also roast peacock dressed in its feathers to show its traditional wheel, and with each peacock bearing the lord’s coat of arms. So too there were “pheasants with fire shooting from its beaks, and other roasted animals cooked and then dressed in their own skins.”[5] The Bentivoglio made a practice of parading these dishes around the piazza outside their house before presenting them to their guests so that the people of Bologna could see just how rich they really were.

Inside the banquet hall there was more sizzling than just the meat. This wedding brought together many enemies and allies. If you were a lord in Renaissance Italy tucking into roast pig at a wedding feast, you could look at your fellow lords and be sure most of them had at least considered having you killed, even your friends.

Of most interest to the diners was the sizzle between Lorenzo Medici and the Lord of Forli. Ten years before the Lord of Forli had arranged for the assassination of Lorenzo and his brother. The Lord of Forli had succeeded in killing the brother but not Lorenzo.[6] It would not be long before the Lord of Forli found himself on the wrong edge of a dagger.

In the Italy of the Renaissance, revenge was a dish best served at any temperature – and at any time.

The feast ended with the presentation of gifts for the bride. These was mostly jewelry and fine fabrics. The father of Hugo Pepoli, future challenger to the duel with Guido Rangoni gave the bride e a diamond set in gold worth 60 ducats. Guido Rangoni’s father also gave her a diamond set in gold, but the one he gave her was only worth 40 ducats.[7] Both gifts paled in comparison to the diamond pendant gifted to her by the Marquis of Mantua – the man who would later host the duel between Hugo and Guido—a piece of jewelry worth 1,200 ducats. Enough money to buy a house.

For the Bentivoglio family a gift like this from a lord like the Marquis of Mantua was one more sign that they had arrived. During the wedding festivities the Marquis would make arrangements to marry one of his younger brothers to one of Grandpa Bentivoglio’s daughters,[8] creating an alliance between the two families. The Bentivoglio had come up from the lower classes of the city and to make dynastic connections with old warrior families was a a huge step up.

The use of marriages to build political alliances was common practice in Italy – but it had huge downsides. This was one of the reasons why Lorenzo de Medici had come personally to Bologna. To keep Bologna connected to Florence, Lorenzo had arranged a marriage between one of his allies, the Lord of Faenza, and Grandpa Bentivoglio’s hot-headed daughter Francesca. These were the parents of Guido’s handsome cousin, Astorre. Things were not working out between husband and wife. Astorre’s father, the Lord of Faenza, was keeping a second family in town. Francesca Bentivoglio was not the type of woman to brook this kind of insult, especially after having delivered him an heir.[9] This created an inconvenient problem for Lorenzo and Grandpa Bentivoglio. The lord of Faenza was essentially a vassal of Florence,[10] and Lorenzo had to take his side while Grandpa Bentivoglio was naturally taking the side of his own flesh and blood daughter.

Eventually, Francesca would resolve the problem by driving a dagger into her husband’s chest, but that was in the future. This wedding would not be an occasion for daggers but for swords and for lances.

The Swordfight

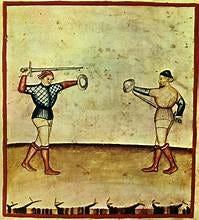

Fencing for pleasure was a common pastime in the Renaissance. Part of it was a matter of improving one’s skill and part of it was just for fun. Fencing was considered a healthy activity. The Tacuinum Santitas, a compendium on medieval health, noted that it was suitable for the young and the hot-tempered and that fighting for pleasure leaves one feeling “lively and light, with a strengthened body and drained of ill humors.” For a Bentivoglio courtier the ability to fence with a foil and buckler was considered as crucial part of being a courtier.[12]

So the next day the wedding party and its honored guests took up a space outside the Palazzo to watch a gladiatorial entertainment — an event far more suitable for young Guido Rangoni.[11] While the wedding party gathered into the square and curious onlookers came to the windows or the rooftops to see what the hubbub was all about, Grandpa Bentivoglio left briefly and then returned with the sword fighters.

Our eyewitness to the event now describes what follows:

“The event begins to reveal the plan,

My lord departs and soon returns,

And with trumpets he arrives in human action,

But behind him, not far apart.

Forty gladiators, each in hand,

Holding swords, in view and every man ready,

To prove themselves in the theater and gain honor, As their lord has commanded them.

They all had helmets on their heads,

For in this game they are often of use,

And to fence without them would be as stupid, as making eggs expensive.

Now we come to the harsh tempest,

On the balcony of the noble palace is found,

The bride, along with the other ladies and great lords; Never were gladiators more honored.

And they removed their rose-colored cloaks,

And all of them remained in doublets,

A sword in one hand and in the other gripping, A buckler—now imagine the delight.

“And so far as I can remember,

I would not want the sight to cause offense.

All of them bear my lord’s insignia,

And their doublets are of silk, as they stand in the field.

And now I see them form a circle,

And a glove was placed in the center of the field. That must be won, as I see them lead the way, With bucklers and swords in hand.

There might be some sign—or perhaps worse.

Now let neither Triton nor the summit boast,

Nor the gladiator bathed in his own blood,

That drips onto the one who languishes for his love.

Now here it is fitting that every time there be a display, The gladiators have rushed to strike,

With great fury and by their agreed-upon law:

Whoever is struck must leave the field.

But because each man is cautious and alert,

First, many blows must be endured.

Now upon the bucklers and swords of both sides, They parry as when a storm descends.

I could not describe in a thousand verses

The blows I saw delivered at once:

Thrusts, cuts, strikes, and reverses,

Montati, falsi, and tramazzoni.

Falsi roversi, some quick, some diverse,

And some you’d see standing in guard.

In one moment, you’d see it narrow then wide,[13] The game: here, one needs the eyes of Argus.

One stands in the Guard of the Falcon,

Another in the Boar’s Tooth, and one in Guard of the Head, Some in Coda Lunga Larga, Alta & Stretta, Or are poised to strike, but the hand moves fast.

They are all quick in delivering their blows,

And yet the buckler is not overly troubled.

And here I cannot believe that among so many

There isn’t one who would win the glove with money.”[14]

As the sword and bucklers of the gladiators clanged with desperate combat, a great crowd was drawn to witness the fight. The small piazza in front of the palazzo could not hold many and the crush was so great, “That if someone had thrown a small apple, it would not have fallen to the ground intact…”

The size of the crowd cut down the room that the fencers needed. Grandpa Bentivoglio shouted for the crowd to back away, but they were so drawn to the spectacle of skill and strength and speed that they dared his wrath.

The proud young Bolognese nobleman Hercules Marescotti took it upon himself to drive the crowd back away from the palazzo, but he was not successful. Here was an ironic moment: he would be remembered as the man who led a mob towards the palazzo, hellbent on it destruction, but that day was not today.

Little Guido Rangoni would have had a perfect view from the second floor windows of the Palazzo, a perfect impression of the ethos of the era for a young mind: the fame of the swordsman is second to none. It was a lesson that Guido would take to heart.

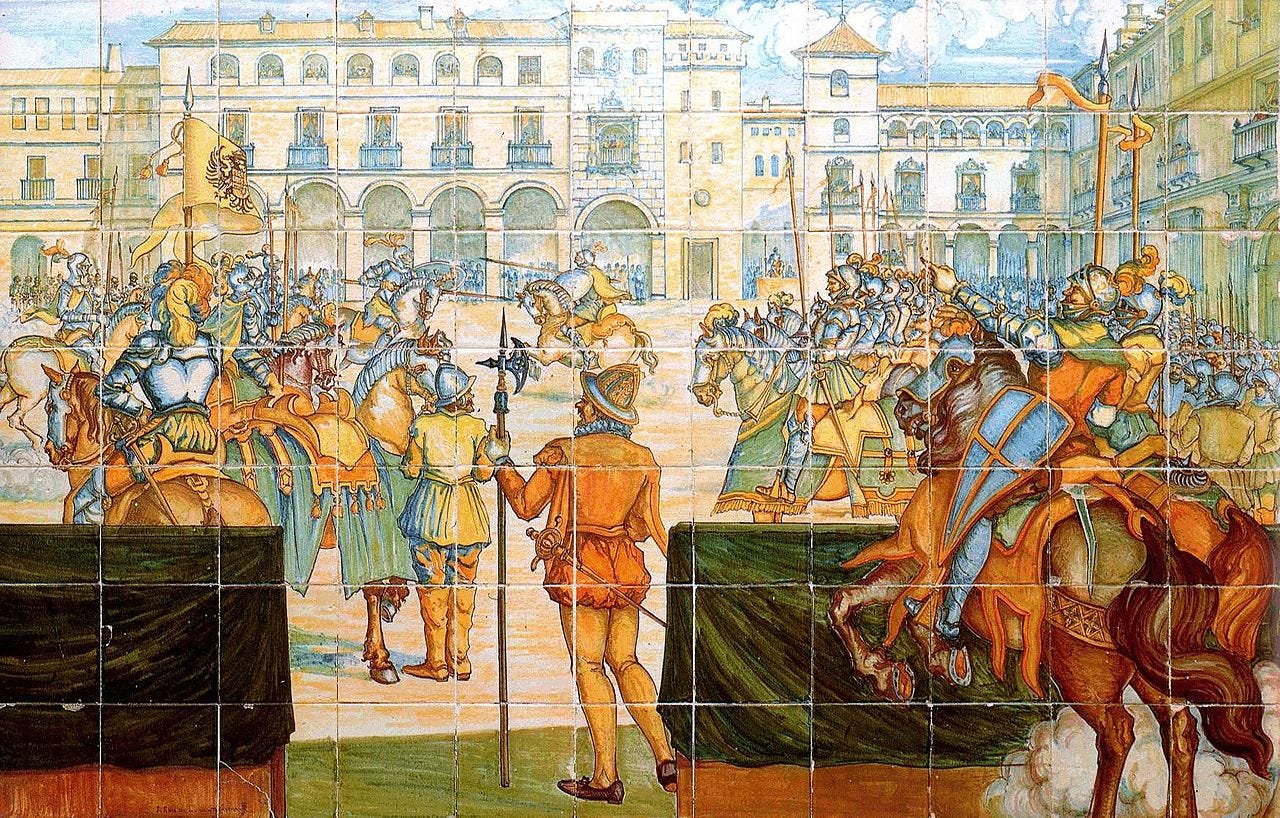

The Joust

The next day the joust was held in the main square of Bologna. The joust was the most memorable part of any good wedding in Renaissance Italy—1487 was still very much the Age of Chivalry. For the armored cavalryman, or man-at-arms as he was known in Italy, the use of the lance on horseback was the supreme test of strength and skill. In our age we can scarcely imagine the effect of concentrating the power and might of a horse into a narrow point, but this an absolutely devastating weapon. A well-placed lance could knock a knight off his horse with so much force that it could take down other three more knights riding behind the target.[15]

The use of the lance required the man-at-arms to hit a moving target only a few inches wide while holding a ten-foot lance. He had to do this not from a stable position or even from his own two feet but while trying to hold his position on a fast-moving horse, an animal that would be moving up and down a bit with each step. He had to keep the horse moving in a straight line by giving subtle pressure with each spur, and had to hope his horse did not react to the sight and sound of another horse rapidly approaching it.[16] In war, a man-at-arms had to perform this difficult operation while another knight was also bearing down on him, hoping to knock him down like a bowling ball scatters pins.

In a joust the knights used lighter lances designed to shatter on contact with the enemy. Instead of a lance point, the lance was tipped with a six-point coronel to catch the lance against the enemy and shatter the lance. In previous days the goal had been to knock an opponent from his horse, but that was less common in late 1400s Italy. Instead the knights were judged on their ability to accurately hit their target while maintaining perfect balance on their mount.

Death and permanent disablement were a key feature of jousts, despite the heavy armor worn by the jousters and the safety lances being used. It was still dangerous. The charging knights aimed their targets at the slit of the opponent’s eyes.1 Many suffered injuries when the point, or splinters from a shattered lance, entered in through this slit in the visor.2Lords throughout Europe suffered permanent debilitating injuries from jousting, and those were the ones who lived.

As the Captain General of the Bolognese army Guido Rangoni’s father had a perfectly good reason to skip the joust, but he would not have missed it for the world.[17] And after Grandpa Bentivoglio kicked off the festivities, Guido’s father was the first to ride into position for the joust. Just as in a duel it was in the custom of a joust for a man to have a padrino or Godfather come with him; Grandpa Bentivoglio host of the festivities also served as the padrino to Guido’s father.[18]

As the toddler watched from the Palazzo of the Signori, Guido saw his father ride beneath him, the visor of his helmet up as he came to one corner of the square. While the whole joust was a lot for a toddler to understand, little Guido certainly would not have recognized his father, riding along, visor up, lance upon his thigh. If Guido looked to his mother, he’d likely have seen lines of worry as Guido’s father took his position.

Our eyewitness records in some fine detail the match between Guido’s father, Count Nicolo Rangoni and the Neapolitan nobleman Sigismond Cantelmo.

.In this first exchange between then, Sigismondo completely missed Guido’s father, because the impact of Rangoni’s lance presumably knocked him sideways on the horse.

“Sir Sigismondo goes against the Count,

And this first time he charged in vain.”

After the first pass, the jousters turned their horses about and faced one another once again. At the signal the two men kicked their horses into action and began another charge, the sound of their horses “thundering” in the great piazza.

"Here Sir Sigismondo returns to the Count,

For he had turned away before.

In a charge, he ran in vain, which is no surprise,

As fortune changes with each turn.

I believe that his adorned figure

Had missed the mark on the first pass.

He spurs his steed forward, earning great fame here,

For he struck the Count, touching him at the visor.

But the Count Captain, as I hear,

Has shattered his lance into a thousand pieces,

So fine that the wind carries them away.

This strike will bring fame to this act.

He remembers that the prize is silver…”

Poor Sigismondo. Though he managed to touch Guido’s father the second time, it did not compare to Count Niccolo’s own strike on him, a strike aimed so true that his lance shattered into a cloud of splinters. For as the joust tested strength and agility, it was even more a test of nerve. The Bolognese writer and warrior Angelo Viggiani noted that many in jousts lean away from the enemy, cause a loss of accuracy and some more “close their eyes as they joust cause their point to miss entirely.”3

Count Niccolo still had another pass with Sigismondo:

“And Sir Sigismondo returns to the Count,

At the middle or thereabouts—I cannot measure it precisely.

He breaks his lance upon the shield with force,

And it seems the red steed carries him too well.

But our Captain stands firm like a mountain,

Who also breaks his lance yet does not move.

With the paladins of France, he would hold his own."

Three passes seems to have been enough against the Neapolitan.

Guido next watched his father take on a Bolognese knight who went by the nickname, “Marquis.” These two knights aligned against one another and with a crowd cheering, sought to break their lances on the opponent.

"Neither one nor the other is satisfied with [a strike to] the shield,

For this does not seem to them a masterful strike.

And they eagerly seek a harsher blow.

But since fate is at times unfavorable,

And strips our thoughts of their intended effects,

Marquis spurs his Florentine steed forward,

Yet still charges in vain; but the other I mentioned

Breaks upon the shield, marking it with this chosen sign."

After breaking their lances unsatisfactorily upon one another’s shields the two warriors took another pass.

“In this moment, the Marquess rushes forward,

Indeed, he has charged twice and missed.

So this time, as I recount his attempt,

He aims the tip of his lance straight at the face

Of Count Niccolò, delivering a blow,

And both of them have aimed for this mark.

They break their lances."

That was enough for Marquis. Guido’s father kept the field and faced more opponents, neither of whom was equal in skill to his first two fighters.[20]

Besides watching his father Guido and his uncle Hermes kept a watch on the bridegroom, Uncle Hannibal, probably the youngest man to be tilting that day. Though young he was “strong” and “dexterous,” and “especially so in tournaments,”[21] the young Hannibal more than held his own that day. Riding a horse “whose reins were slick with foam from his exhausted horse,” Hannibal obtained one clean hit after another, while making his opponents miss.

Still his skill was not enough to make him victor for that day. Nor were the victories of Count Niccolo. The laurels of victory went to the Marquis of Mantua. For his fine demonstration of martial skill the Marquis received a banner made silver brocade.

The joust was a rousing success. Although there were some close calls – one knight had the helmet knocked clean off his head – there were no serious injuries to any involved. All would live to fight and joust again.

Parting Is Such Sweet Sorrow

The next morning, the guests of the wedding departed for their respective destinations, plotting and scheming to pass the time of journey. It was estimated that over 3,000 visitors attended the grand celebration. The bride and groom settled into their new lives and little Guido returned to the family castle in the countryside.

Little Guido probably had no memories of the event but we can easily see the impact of the culture of the nobility on the budding young knights of Italy. Theirs was a world of jousting and sugar castles and beautiful gifts for the great lords and their warriors. A world where noblewomen were draped in silver- and gold-brocade. A world of chivalry, where bravery and mercy for a defeated enemy went hand in hand. A world where a knight could go into battle and fight without much fear of actually being killed.

The era of the knight seemed as permanent on that January day in 1487 as it had five centuries before. A world where the armored warrior on horseback with his lance stood above all other men as the alpha and omega of war. Likewise, the wealthy and independent Italy, the Italy that had led Europe from the chaos and poverty of the dark ages into a prosperous new era, this too seemed as permanent as the sun rising in the East.

But the clouds stood just beyond the horizon. An Armageddon for this world approached, a reckoning that would change everything. None suspected that soon lowborn peasants with pikes would be chasing knights away from the battlefields while cannons pounded their castles into brick dust. The announcement of this change would be sooner in coming that anyone could expect -- just a few months later an army of Italian knights would be butchered like hogs by German mercenaries recruited from the lower orders.

Those mercenaries known as landsknechts.

And Italy would be rent, raped, despoiled and left destitute by these landsknechts as well as by French Gendarmes, Gascon Crossbowmen, Spanish rodeleros and Italian mercenaries as they crisscrossed the peninsula and stripped it bare like so many swarms of locusts.

And young knights like Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli, men trained with the lance and the sword, would have to learn to depend more on their wits and guts than their arms.

[1] Ghiradacci, p. 236.

[2] Ghiradacci, p. 241

[3] See Ghiradacci, p. 272.

[4] Ghiradacci does not specify who was there beyond some noblewomen. It is only an educated guess that those grandchildren out of swaddling clothes would be present. It seems also likely that as the leading lady of the second most prestigious family in Bologna, Hugo Pepoli’s mother would also be present, but this is supposition. Also note that there is no mentin of the children being present, this is just an educated guess based on the reasons provided.

[5] Ghiradacci, pp.273-274.

[6] The presence of the Lord of Forli, Girolamo Riario, can be inferred from p. 240 where Riario is personally given a confection of sugar in the shape of a castle.

[7] Ghiradacci, p.239.

[8] This would be Laura Bentivoglio who married Giovanni Gonzaga in 1491. We do not know for a fact that this was when the wedding was arranged, but this would have been an ideal time for the Marquis to see with his own eyes that the girl was a suitable addition to the Gonzaga clan.

[9] This is a fascinating side story that is sadly beyond the scope of Death Before Dishonor. Astorre’s father Galeotto Manfredi was keeping a second wife known as the Peacock in their hometown of Faenza with their children and in a conflict over this (and other matters) he had publicly slapped her in the face. Astorre’s mother, the hot-tempered Francesca Bentivoglio then snuck out from Faenza and went to live with her son – and heir to Faenza – in Bologna. This was a matter of great public shame for Galeotto Manfredi but he refused to send the Peacock away.

[10] See Storie di Faenza by Tonducci, for example, “that year, the Florentines, having summoned the Count of Pitigliano, ordered Galeotto Manfredi and their other principal commanders to assemble their forces and take the field as soon as possible,”

[11] Ghiradacci p. 239

[12] See Art of Arms: Knights of Viola (or follow the link)

[13] That is with the point facing the opponent (narrow) or point facing away from the opponent (wide)

[14] Salimbeni p.70 of 112. (Source is electronic with no page numbers)

[15] See https://theartofarms.substack.com/p/how-fiore-dei-liberis-protege-helped-37f.

[16] See the Art of Defense, Swanger.

[17] It is also possible that Guido’s father was only the Captain General of the Men-at-Arms.

[18] For the role of the padrino in the Bolognese Joust, see Miscellanea Storico-Patria Bolognese by Giuseppe Giudicini, edited by F. Giudicini, pp. 182-201. The assumption that Grandpa (Giovanni) Bentivoglio served this rule is intuited by “with him,” since the “him” in question was “my lord,” and presumably referred to Giovanni Bentivoglio as the author was a member of the Bentivoglio court.

[19] The various exchanges in the joust are described in great detail on pp. 78 – 107 of Salembini.

[20] As Ghiradacci describes the next two fighters he faced were Giulio Tassone and Annibale Bianchetti. See Ghiradacci, p.241.

[21] See www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Annibale Bentivoglio.” Note this attributed to Sansovino, presumably Francesco Sansovino but I was unable to locate the source of the quote.

See The Art of Defense, Swanger, p.77.

Ibid, p.83

Viggiani, p.60