Conte di Castiglione: Part 1, Sins of the Father

Giovanni dall'Agocchie Part 3: Patron

Introduction:

In the introduction of Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s, Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre, published in 1572, he dedicates his work; on fencing, the joust and battle array, to The Very Illustrious Count Fabio Pepoli, Count of Castiglione—his Lord and always observant patron. Who was this Fabio Pepoli? In this honorific introduction, Giovanni not only signifies that Fabio was his patron, providing financial support for his finished work, but he very specifically calls him, my Lord, and follows this with the line, “The knowledge that since your tender years your illustrious Lordship has greatly delighted in the virtue that pertains to an honored Knight, and the spirit that I have always had to serve you and do you gracious things, have often made me desire to be able to make some sign thereof unto you.” Tender years was a legal term, generally referring to the age before one was able to give legal consent, and ranged from 12-14 years-old.

This indicates that Giovanni knew Fabio in his youth, and continued to serve him until—at very least—the publication of Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre. This is further indicated a few lines later, when Giovanni states, “I present it to you thus, not in order to even with you via this humble gift the debt that I owe you, which is so far beyond the reach of my feeble abilities, but to leave you with some testimony of my adoring servitude,” denoting that Giovanni served his lordship in some capacity.

After concluding his honorifics, he gives the purpose of his work:

As fencing is the chief part of military exercises, one sees that it is conclusively necessary to men. Given that in times of war we wish to have use of it, what may be more convenient to us? And among bodily exercises, which is more noble and illustrious than this one? And since a man may be constrained and forced by the circumstances of war to exert himself therein, then for what reason wouldn’t anyone seek [3verso] to have a full understanding of this beautiful and useful profession? I am silent regarding those bouts of honor which are called “duels”, in which no one may account for himself honorably, should he be wholly ignorant of this.

In consequence whereof I do not hold these discourses of mine to have turned out to be useless. I have composed them in the form of a dialogue for their more ready understanding by whomever in whose hands they arrive. In precisely that fashion did it pass that I had discussions thereof in Brescia, in the house of the very illustrious Signore Girolamo Martimenghi, with Messer Lepido Ranieri, a youth of a sensible and virtuous bearing, who well understands the practice of fencing. After many discussions with him, both of us being led to the garden, he began to speak thus:

—Giovanni dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 3

There are clues about Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s life riddled throughout his introduction and his text. To better understand these, we have to understand the life of his patron Fabio Pepoli, and the legacy of the Pepoli Family.

Pepoli di Castiglione Origins:

To begin this voyage into the life of Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s patron, we should first outline what it meant to be the count of Castiglione, and then briefly examine Fabio Pepoli’s maternal and paternal lineages.

The title of Count in Italy was at times a superficial moniker of nobility, that is, there wasn't always a county or significant region of influence associated with the title.1 That was not the case with the County of Castiglione. The center of Pepoli influence, today Castiglione dei Pepoli, was a sizable enclave in the southwest territory of Bologna that sat along the crucial north-south corridor linking the city with Florence. The counts of Castiglione had the power to levy taxes, tariffs and tolls along this route, making them powerful figures in the key trade industries that linked the embattled republics—notably silk and wool.

When Giacomo and Giovanni Pepoli, the sons of Taddeo Pepoli, purchased the county in 1340, from Count Ubaldino degli Alberti di Mangona, they attained the villa of Bruscoli, the Castle in the region, and 72 farms, along with the right to “exercise the jurisdiction of mere and mixed empire.”2

For perspective, according to the Italian Encyclopedia, Castiglione; in the year 1931, included a territory that spanned 63.54 km, which encompassed Mount Gatta, where the capital of the county is located at an elevation of 691 meters. The territory, “produce(d) wheat, corn, chestnuts; with good pastures and plenty of wood for coal and firewood; there are also a few grape varietals; as well as mills and pasta factories.”

The title of ‘Conti’ was later invested by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV, in 1369.3 However, in the late 14th century, the Pepoli family saw a considerable collapse in influence after Republic of Bologna was ceded to the ever-expansive Visconti; which Giacomo and Giovanni Pepoli sold to Cardinal Giovanni Visconti for 170,000 gold florins, while maintaining their claims on the territories of Castiglione, San Giovanni in Persiceto, Crevalcore, Cento, Sant’Agata, and Nonantola. This was soon followed by the liberation of Bologna during the War of Eight Saints, and the rise of a new papal regime under the Legate William of Noellet.

In September of 1376, the Pepoli-sympathetic Scarchessi faction4 overthrew the papal regime, and ousted their Maltraversi opponents. The faction then split into the Pepoleschi and Raspanti coalitions. The Bentivoglio-led Raspanti briefly claimed power and exiled the Pepoleschi adherents, but were soon removed from their perch. As a consequence of these successive upheavals the repatriated Maltraversi confiscated many of the assets held by the families aligned with the Scarchessi factions.

Guido, the son of Giovanni Pepoli, would then be exiled in 1390, and have Castiglione taken from him by the Bolognese Regimento; who destroyed Castellaccio Castiglione. However, in 1394 the Regimento returned his titles and compensated Guido 2,500 florins for the brash actions of the previous regime.5

In 1400, the Pepoli were at it again, and attacked Bologna from Ferrara after the regimento confirmed Giovanni I Bentivoglio as Confalonieri del Popolo for life, but they were turned away by the condottiere Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia. They would later return, and regain their assets in 1402 after the Battle of Casalecchio del Reno, which led to the capitulation of the Bentivoglio regime.

After a brief subjugation by the Visconti was followed by that of the tyrant Facino Cane—after the death of Gian Galeazzo Visconti in 1402—Nanne Gozzadini and Cardinal Baldassare Cossa returned Bologna to a state of liberty in 1403—albeit under papal control. This reprisal was marred by infighting between the powerful Gozzadini family and the ambitious legate. Gozzadini was eventually exiled from 1403 to his death in 1407, whereupon Cossa was allowed to reign unchallenged. His proclivity toward corruptible nobles, and disdain for the powerful guilds in Bologna created a contentious political atmosphere. This unstable relationship culminated in the 1411 Bolognese Butchers Revolt. After a brief populist rule led by the artisan guilds, the Pepoli; notably Guido, Galeazzo, and Ricardo, instigated a new revolt in favor of Cossa’s legation and the nobles of the city, and ousted the guild-led government in August of 1412.

In the wake of this turmoil, Antongaleazzo—the savvy son of Giovanni Bentivoglio; now in his 20’s—briefly came to power between 1416 and 1420. During this period, he made a number of transcendent political moves by uniting the Bentivoglio family with all of the key power brokers in the city. First, he gave his sister Giovanna’s hand in marriage to his key ally Gasparo Malvezzi, then he married Francesca Gozzadini; of the powerful Gozzadini banking family; the ancestral leaders of the Maltraversi faction, and to further strengthen his coalition he united his daughter Isabetta to the Count of Castiglione, Romeo di Guido Pepoli; scion of the heads of the Scarchessi faction, who, as stated controlled the key route to Antongalaeazzo’s chief external ally, Florence.

On account of this union, Romeo Pepoli became a key contributor in the maintenance of the ascendant Bentivogleschi faction, until 1449, when he rebelled against the reigning regent Sante Bentivoglio along with members of the Fantuzzi and Viggiani families. Romeo believed that Sante was exercising tyrannical control of the city and it's territories in pursuit of the rebellious Canetoli faction.

A little ancestral and martial arts aside here: Romeo’s son Guido married Isotta Bernardina Rangoni, and had Girolamo Pepoli in 1494—whose cousin Ugo Pepoli would fight a duel with Guido II Rangoni in 1516, while Ugo's brother Filippo would stand as padrino for Niccolò Doria in a duel dated 1529.

Girolamo wed Giulia Conte in 1511, and had two sons Fabio (born March of 1538) and Sicinio (DOB uknown), and a daughter Sulpizia (1530). Notably, Fabio’s mother Giulia was a descendant of the powerful Roman patrician family, the Conti, who were heavily intertwined with the Colonna—a point of reference that will become important later. A note of interest about Girolamo’s early life: he was the Magistratura dei Gonfalonieri of Bologna in 1523, and spent considerable time in Rome, working with the pontiff, Adrian VI, on eliminating a number of counties granted by Pope Leo X, with the intent of stripping his rival Melchiore Ramazzotto of his rural powerbase in Bologna.6 This coincides with Antonio Manciolino’s appearance in Rome.

Sins of the Father: Guelf vs Ghibelline

The foreign invasions had given a new meaning and a fresh violence to these long-lived factions. The Guelphs were now the French, the Ghibelline the Spanish or Imperial party. The survival of these factions intensified the dissension, not only of Italy, but of her several states and towns, for all local or family quarrels became sooner or later merged therein. The history of most towns in the Papal states during the first half of the century proves how much of the energy of the population was exhausted in this feud, which was a source of weakness even in cities under the stronger rule of Milan and Venice. Every Italian theoretically wished for the expulsion of the foreigner; the barbarian dominion, in Machiavelli's words, stank in the nostrils of all.

(Armstrong, pg. 133)

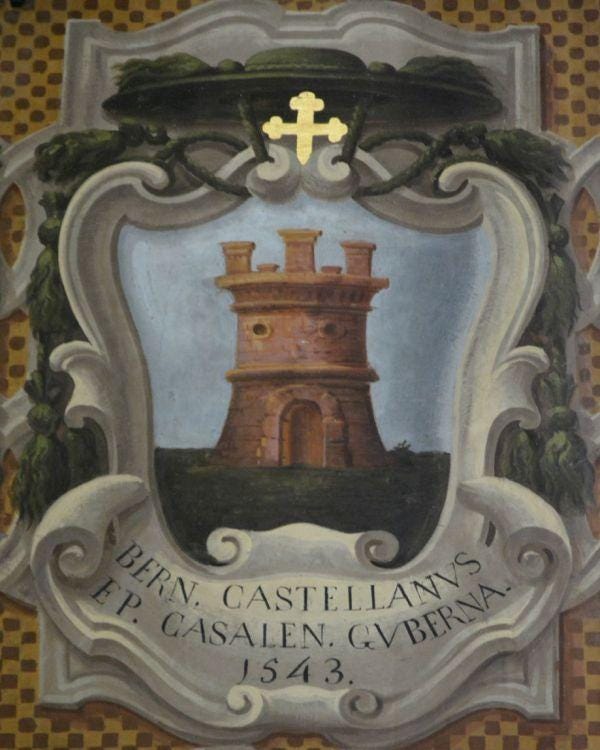

By the 1530’s the Pepoli family remained one of the most powerful Guelf families in Bologna and much of northern Italy. For example, in the late 1520’s, Conte Ugo Pepoli—upon the death of Giovanni della Bande Nere—became the captain of legendary Black Bands, and proved a constant thorn in the side of the Imperial forces in Italy on behalf of the Florentine Republic and the Kingdom of France. While Ugo’s brother Filippo Pepoli became a senator in Bologna; where he advocated for staunchly Guelf policies, and their cousin Girolamo Pepoli served as a captain for Federico Gonzaga and Alphonso d’Este; while also feuding with the Ghibelline captain Melchiore Ramazzotto. On account of this, the Pepoli family made powerful enemies among the Imperial diplomats and advisors occupying the peninsula; notably Bernardino Castellari, Bishop of Casale di Monferrato.

Even after the death of Ugo in 1528, Castellari continued to seek retribution against the ever contentious Pepoli family—who he saw as the source of his perils in pacifying northern Italy. In 1530, when he temporarily assumed the role as Vice-legate of Bologna he, “tried to oppress those gentlemen who seemed to him to have too much authority,” (Vizzani, pg. 2)—notably the Pepoli.

That didn't work out the way he had hoped.

Castellari had been given the unenviable task of alleviating the continuous political divide in the city of Bologna for Charles V's coronation as Holy Roman Emperor. His conduct in the planning of the Siege of Florence alongside Ferrante Gonzaga, showed his capability as an administrator. However, there was a stark difference between military occupation and facilitating civil obedience.

The coronation was peaceful, and a testament to the magnificence of the Bolognese people and their beloved city. However, what Castellari didn't anticipate was the conduct of the Spanish and German soldiers. At the conclusion of the coronation, a group of Spanish knights, restless and unimpressed, disrespected a pair of Bolognese noblemen— Camillo Gozzadini and Marc’Antonio Lupari; both senators.

Naturally, swords were drawn, and the heavily disadvantaged Gozzadini, Lupari, and their servants got the worst of the fight, with Lupari taking a rather serious wound in his thigh. After retreating to the Lambertini Palazzo, Gozzadini and the remaining retinue returned to the square in masse and extracted their vengeance on the Spaniards, to “whom they gave many wounds.” (Vizzani; Book 2, pg. 555)

The violence didn’t end there. Gozzadini went to the one man he knew could foment the right amount of trouble—Girolamo Pepoli, who called together a council of Bolognese noblemen, and together they explained everything that had just transpired. Collectively, they decided that the honor of their city needed to be restored, and roved through the streets at night, killing every Spaniard and German they could find, dumping their bodies into the sewers and vacant wells of the city.7

“{Girolamo} Pepoli, along with certain other leading gentlemen; each rallied a host of many young Bolognese, in whose company they went around the city at night and killed as many Spaniards and Germans as they encountered in the dark: for which reason, since the Spaniards had already lacked some pride, inevitably lost all courage to go around the city at night(.)”

—Vizzani; Book 2, Pg. 555

The Spanish Captain General, Antonio da Leiva, and Camillo Gozzadini were called before the Pope, Clement VII, in an attempt to facilitate peace. Levia, explained the situation, “we carry our arms for reasons of chivalrous nobility, and to dissuade those who recklessly try to insult us, and thus for our defense, and by the service of the Supreme Pontiff we will bear them with the good grace of his Holiness,” to which—in a bid to assure his Holiness that he could maintain peace—he added, “we have put the shackles on in Milan, and perhaps we will put the shackles on again in Bologna.”

To which Gozzadini famously replied, “In Milan they make needles, and in Bologna we make daggers, and there are people who know how to put them to work.”

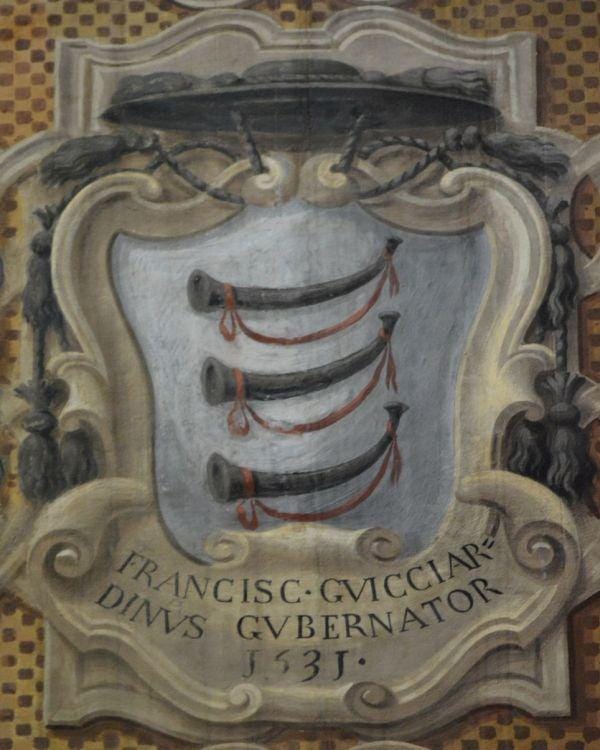

On account of his involvement in the ‘uprising’, Girolamo went into a self-imposed exile8, taking a papal condotta in Pistoia before settling in Castiglione, but would tentatively return after Castellari was replaced by the later famed Florentine Chronicler, Francesco Guiccardini—the only non-ecclesiastical legate in Bologna’s history.9

There was no love lost between Guiccardini and the Pepoli either, the shift of Florentine politics into the realm of imperial control after the aforementioned 1529-1530 siege of Florence and the re-installment of the Medici family as the heads of Tuscan Republic, under the leadership of soon-to-be duke Alessandro de’ Medici, meant that the Pepoli were once again at odds with the reigning legate of Bologna.

Fabio’s father Girolamo, who was now entrenched as one of the de facto heads of the Pepoli family, proved to be the biggest thorn in Guiccardini’s side, even from afar. The trouble with the new legate started in 1532, when Clement VII, actualized and expanded Adrian VI’s entitlement policy that Girolamo had helped craft in 1522, which stripped a number of titles that were bestowed upon Bolognese nobles by Pope Leo X. But, Clement—Leo’s cousin—added those titles given by Francis I the King of France, which enraged the Bolognese Guelfs.10

At the same time His Holiness, Clement VII, doubled the tithes on ecclesiastical benefices in Bologna, and commanded that every household in the city pay one gold ducat per family or residence, in order to bankroll his continued war efforts; which Guiccardini was in charge of enforcing.11 The Sedici agreed to open the cities coffers to cover half of the estimated 16,000 ducats that the tax would inevitably levy, but that wasn’t enough for the popolo. The Palazzo of the Gonfalonieri was flooded with Bolognese citizens begging for remittance.12

The citizens within the city were eventually seduced to reason, but the rural mountain-folk took up arms under the leadership of Camillo Sacchi, with the support of Girolamo Pepoli. Guiccardini ordered this revolt to be suppressed by the notorious condottiere Melchiore di Ramazzotto. The aged captain they called, the priest—for how many souls he’d sent to St. Peters gate— annihilated the rebels, and sacked the hamlets and municipalities suspected of supporting his adversaries. It wasn’t a good look for Guiccardini, who was already treading thin ice.13

Of course, the last thing a city strapped with undue financial burden and teetering on the edge of revolt needed was a state visit from the Holy Roman Emperor—and—the Pope. Alas, in 1533 Charles V put an Ottoman army to flight in Hungary, so Papa Clement invited ol’Chuckles to Rome for some well deserved kudos and a long discussion about the future of Christendom. But, Chuck didn’t like Rome—for reasons14—and asked His Beatitudes if they could meet in his favorite Italian city—Bologna—instead.

Clement was having trouble of his own in Rome, he’d just issued a city-wide weapons ban and confiscation program to curb the violence plaguing the city. A misstep which would eventually see his governor in charge of enforcing the matter, Gregorio Magalotti, get his hand cut off by the Gonfaloniere of Rome, Giuliano Cesarini. The drama unfolded like this: the governors cronies tried to publicly confiscate Cesarini’s weapons, and followed this affront with a raid on his families estates, and thus provoked and act of revenge. Cesarini assembled a number of armed men and jumped the governor and his halberd-wielding escort with swords. Magliotti’s escort was overwhelmed by Cesarini’s swordsmen and killed, then in the final moments of the exchange, Magliotti tried to stop a sword blow to his head with his hand, and lost the appendage—but preserved his life.15

Bologna would do just fine.

The problem was, Charles didn’t come alone. He brought his whole court, his army, and every packhorse and mule from the Danube to the Rhine. The Pope, not to be outdone, saddled 14 Cardinals, 18 Bishops and as many prelates he could fit on his gilded pope wagons.16 This time Charles was smart enough to keep his army, his captains, and a majority of his high ranking officials bivouacked outside the city, as he didn’t want to rehash the ass-whooping his Spaniards and Germans took after his Coronation in 1530.17

Not all of his generals stayed in the contado however, Charles’ best friend and most-trusted military advisor Ferrante Gonzaga18—and we can certainly speculate Ferrante’s highly lauded Bolognese captain, Angelo Viggiani dal Montone—were allowed to join in on the festivities. The mobile enclave and Imperial court stayed for almost two months, and capped-off their visit with a Carnival celebration which saw Chuck suit up and take on his pal Ferrante with spear and stucco at the barrier.

When the time of Carnival arrived, numerous games and festivities were organized throughout the City to entertain the Lords and gentlemen of the Court. Notably, some tournaments took place in the palace, one of which featured Emperor Charles, who wished to engage in combat with Don Ferrante Gonzaga using a pike and a stucco. In this contest, both participants, clad in shining armor, displayed remarkable skill and boldness, much to the delight of the Princes and the other attendees.

—Vizzani, pg. 6 (1533)

The year was now 1534; the cups had run dry, the coffers were emptied, and the party had come to a grinding halt, so everyone returned home. The excitement didn't end there, however. A few months later, ill tidings were brought back from Rome—Pope Clement VII was dying. This was sorrowful news for some, and splendid news for many, but for our languid chronicler Francesco Guiccardini this was devastating news. Without the muscle of the Pope and his Cardinals, he and the fledgling Medici dukedom were feeble, vulnerable, and surrounded by enemies. The Bolognese Regimento took pity on him, and lent him a hand, by sending 900 infantry to guard the Piazza Maggiore and secure the twelve gates of the city.19

Then, on the 25 of November—it happened—Clement croaked.20

In a mad dash Guiccardini tried to flee Bologna, but members of the Sedici and Anziani stopped him; knowing the inevitable maelstrom his departure would promulgate. They implored him to stay, and see the transition out, promising him whatever resources he needed to remain safe; a deal which he reluctantly agreed to accept.21

Guiccardini quickly passed restrictive legislation that would isolate any ambitious families looking to capitalize on the chaos. This did little to dissuade Girolamo Pepoli, and Galeazzo Castelli; one of the recently curtailed counts, from making a triumphal return to Bologna. Who, accompanied by squads of armed men; inundated with scores of notorious bandits from the contado, made a deliberate mid-day march through the gates, and into the city.22

This defiant show of force was met with considerable fanfare, as droves of sympathetic citizens and frustrated commoners flocked to welcome them home. Guiccardini was incensed, but quickly found retribution when one of his birri reported that two of the bandits in Pepoli’s retinue were wanted criminals. He immediately had these men arrested and executed without trial.23

When word of this reached Girolamo Pepoli, he called his men to arms, and marched on the Piazza Maggiore to confront Guiccardini over this blatant subversion of jurisprudence. However, his rabble was met in the via delle Chiavature by a throng of Senators who talked sense into Girolamo,24 and convinced him to disband his flagrant horde; as he didn't want to upset his friends in power.25

Guiccardini soon-after vacated his legation in 1534 and returned to Florence where he advised the now vulnerable Duke, Alessandro de’ Medici. Vizzani notes that the entirety of this episode, left such a bad taste in Guiccardini’s mouth, that he never found the means to forgive the Bolognese people for their insolence, writing:

But Guicciardini took {Girolamo}’s boldness very poorly, holding onto a bit of resentment towards all the Bolognese. This is evident in the histories he wrote, where he rarely mentions them without some underlying insult. It’s amazing how some people can hold onto anger for so long.

—Vizzani, pg. 8

This resentment and vindictive disposition toward the homeland of a heated political rival wasn't entirely unique to our antagonist Guiccardini—it also infected our protagonist Girolamo. Later, in 1537, Lorenzo de’ Medici violently murdered his beloved cousin Duke Alessandro de’ Medici in a scandalous affair, which saw Lorenzo arrange a secret sexual encounter with a particularly beautiful widow in Firenze on behalf of the duke, all so he could lie in wait with his servant Piero di Giovannabate and stab Alessandro to death in the middle of intercourse.

After plunging his dagger into his balls-deep brethren and getting a finger bitten-off for the trouble, Lorenzo wrapped his cousin in a carpet and buried him in an unmarked grave, then fled to Bologna, with the design of enshrining himself as the new Duke of Florence with the aid of fellow exiles in the city.26 One of his key Bolognese allies in this endeavor, was Girolamo Pepoli; who was keen on abetting the dissolution of the beleaguered Florentine dukedom barely hanging on under the leadership of Alessandro de' Medici’s key advisor—Francesco Guiccardini—one can only imagine why…

As Pepoli was preparing his soldiers for war, he was handed an interdict by papal nuncios in the charge of Pope Paul III, insisting that he desist from aiding Lorenzo any further. So, he turned his efforts toward funding Filippo Strozzi’s conflict with Cosimo I de Medici instead, but it wouldn't take long before this edict was expanded to anyone who contributed funds to Pepoli’s enterprise, and his support quickly dried up.27 After the intervention of Cardinal of Santa Fiora, Guido Ascanio Sforza, he desisted from his war efforts entirely.28

A year later, in 1538, our principle protagonist, Fabio Pepoli; Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s patron, was born. Soon after, in 1541—after the death of Guido II Rangoni—Girolamo supported the claim of Baldassare Rangoni in Spilamberto, sending 200 infantry to ward off Imperial ambitions. Then, later that year, Girolamo moved his family to Lombardy, where he was tasked with the governorship of the Terrafirma; ie. Brescia, Verona and Vicenza on behalf of the Serenissima. It was there that Fabio would have his formative years, likely in the company of the host of Giovanni dall’Agocchie's dialogues, the Venetian Captain Girolamo Martinengo; who worked closely with Girolamo.

Fabio and his mother Giulia returned home to Bologna in November of 1549—but not long after Girolamo was called back to Venice, and briefly served in Hungary.

“I have also been informed that Messer {Girolamo} Pepoli, who now serves as captain general of the Venetians, a man with a large following on the Bolognese mountains, could be of great assistance to us if we knew how to draw him to our side."

—Francesco Burlamacchi (1548) {Wandruszka; pg. 3-4}

Then, in 1551, while in Brescia, Girolamo passed away at the age of 57. Fabio was 13.

Fabio Pepoli and the Malvasia Feud: Like Father—Like Son

Background:

In the wake of all of the turmoil promulgated by the Pepoli family, they had quite naturally drawn the the ire of penitent and ambitious families in Bologna willing to please the powers that be to get ahead—notably political stalwarts like the Malvasia Family; who were prominent figures in the pro-Imperial Ghibelline faction.

For Fabio, who was now entering the perilous trials of early manhood, his cousins Giovanni di Filippo, Girolamo di Sicinio and Guido became his intrepid ancestral guides; along with the memory of his late father, and his heroic forebearers.

Giovanni di Filippo, assumed the role of faction leader after the stalwarts of the early 16th century generation all died rather young. He’s a fascinating character, whose tragic life will form the focal point of this epic tale. In a world where marriage for alliance was the standard, Giovanni shirked the tradition and married for love, wedding a woman of lower nobility, named Vincenza Manciolino; with whom he would have four children, three sons and a daughter. In 1550 when his father Filippo died, he assumed his father's seat in the Sedici, the cities Senatorial body, and it was through this appointment that many of this generations troubles would arise.

Under the guidance of his cousins, Fabio’s first real test came at the tumultuous age of 21, in 1558, while his family was embroiled in a territorial struggle with the aforementioned Malvasia family. Giovanni Pepoli instigated the feud with the Malvasia by advocating for “the republican prerogatives of the city and the glorious institutions of municipal origin: the magistrates of the Elders, the tribunes of the Plebs, and the corporations of the Arts” (Casinova; web).

While the Malvasia, notably the formidable senator, Cornelio ‘Quaranta’ Malvasia, advocated for the enshrinement of papal and Imperial authority. This set the two families on a collision course that would scandalize the later half of the 16th century, and turn the Pepoli family into pariahs—or the champions of liberty—depending on your predilection.

A Dish Best Served Cold:

Quaranta, likely at the behest of Cardinal Carassa, saw an opportunity to leverage the law against the ancestral indemnities of the Pepoli, thereby weakening their hold over key civic assets that had long been utilized for the enrichment of the family. In 1558, he challenged Fabio’s claim over a mill and portions of the Savena canal. This reproach of the young upstart quickly turned heated when insults were exchanged between the two knights. Giovanni Pepoli had to intervene before things got out of hand. With the matter now in the control of his senatorial cousin, Fabio, probably felt like a balanced resolution was on the horizon, but after Giovanni deliberated with their bitter rival, he unexpectedly conceded the assets to Quaranta’s directive, leaving Fabio with no choice but to relent and walk away with nothing but a half-hearted apology from Malvasia.

Fabio—naturally—refused to let it go; he was 21-years-old which means his prefrontal cortex wasn’t fully developed and he was full of testosterone, but those are modern excuses, this was Renaissance Italy, his reputation was at stake—his reputation was everything. So, as he was packing his bags to head to Vincenza, on his first condotta; in the service of Venice, he called the steward of his house to his rooms, and gave him a directive— ‘when we arrive in Vincenza, find me two men capable of assassinating Quaranta Malvassia.’

On the 22nd of March, two strangers arrived at Palazzo Pepoli. The first, named Orazio who, “was tall, of good standing, with a round red beard; {and wore} a pair of yellow stockings tied with velvet, a white collar, and a black velvet cap, with white boots. While his companion {whose name was not recorded} was somewhat shorter—by about half—and wore a black beard; {and} was dressed in all black without a cape.”29

Upon their arrival, Orazio and his companion were entertained by Fabio’s mother Giulia Conte Pepoli, and Giacomo Pepoli, one of the heads of the household. It so happened that while the road weary sojourners were supping on their meal, and enjoying the delights of the Pepoli’s company, Orazio stopped the valet who was serving the party and said, “Oh valet, I would like you to do me a favor, I want you to go early tomorrow morning to the house of Sir Antonio Vittori, and tell him on my behalf to give you that horse he had promised me, and then I want you to leave it here in the stable, because I have a job to do.”30

The valet acquiesced to signore Orazio’s request, and early the following morning went to Vittori’s stable, where he procured a grey and white horse, along with some tack, and tied it up in the Pepoli stables for his master’s guests. Not long after the his return, the valet reported seeing the nameless companion duck into the stables atop a sorrel horse with Orazio in tow; on foot. The shorter fellow dismounted and tied his reigns to a post, then told Orazio, “You should put that bridle and tack on the horse so we can finish the job.” Orazio complied with his companions directive. Then, once his girth was cinched, and the cold steel bit leveraged in the bite of the painted beast, they were ready for the mad dash ahead, and left to do their job on foot.31

The Soldiers were next spotted loitering around the Piazza Maggiore; where the companion leaned into the corner of Chiavature32, while Orazio walked the Odofredi Portico near the Sampieri Palazzo33.34 When they spotted Quaranta and his escort; who were approaching in full livery, armed with swords—they moved. Orazio stalked the retinue beneath the Muzzarelli portico, and veered ever closer to the target, making sure not to alert the detail, until finally, when within striking distance, he lunged at Malvasia. His dagger lodged into the shoulder of the senator, and once ripped free, he drew it’s honed edge across the old man’s face. His companion moved to bring his dagger to bear from the other direction, but the guards had already unsheathed their swords and formed a perimeter around their charge.35

The pair of assassin’s realizing their moment had passed, retreated down the portico back toward Via Clavature; with Malvasia’s guards hot on their heels. At the end of portico, they heard the wounded Senator chastise their failed assail with a shrewd shout, “run back—run back {you cowards}!”36

When Orazio and his companion reached the open doors of a nearby palazzo at the end of the portico, they ducked inside. Malvasia’s guards slowed their pace, and carefully followed them in, but Orazio surprised one of the retinue by putting his hand on the man’s shoulder, whereupon he said, “stay back, stay back, or you’ll be cut to pieces.” The startled band decided to abandon the palazzo, and return to their master, fearing there were more bandits lurking in the cavernous halls of the vacant palazzo.37

Orazio and his companion made it back to the Pepoli’s stables, where the latter ditched his blood stained dagger in the manger, before the pair rode off toward the San Stefano gate.38 As the assassins trotted into the contado, the campanaccio—the cities warning bells—started to ring. By order of the Podesta the public palaces were locked down, shops were to be closed, and gates of the city were all shut until the murderers were found; as per the public proclamation of 1294.39

Witnesses in the area saw the assassins sneak into the Pepoli stables, and alerted the constabulary, the Bargello, who raided the families Palazzo. They took Giovanni Pepoli’s bravo, Matteo Pagnoni into custody; Pagnoni was a wounded veteran that Giovanni had taken in, clothed, fed and given money, in return for his protection.

Despite Giovanni having a member of the esteemed Boccadiferro family entreat with Quaranta on his behalf—to which Malvasia attested he was completely confident in Giovanni’s innocence—Giovanni, and two other Pepoli cousins faced short sentences, which they were able to commute with 1000 lire guarentee’s. Payments which were voluntarily paid by the Isolani and Amorini banking families.40

After scouring Palazzo Pepoli, the Birri canvased the stable—where the attackers had reportedly fled—and it was there, in the manger, that they found the suspects weapon. They took all three of the Pepoli’s valets into custody: Domenico, Menghino and Giovan’Maria—and that’s when the trouble started.41

At first they stuck to their story; that a grey and white horse had passed through the stable and then run away, but after being put though the same line of questioning again, Domenico cracked, and confessed that the horse belonged to a man named Orazio who had gone to Venice with Conte Fabio, but later returned and had dinner with the Contessa Giulia.42 The investigators circled back to Giovan’Maria who they questioned more thoroughly, and when he refused to amend his story, subjected him to torture. He confessed to everything: that Antonio Vittori, the son of Doctor Benedetto had lent the grey and white horse to Orazio at Conte Fabio’s request a few days prior.

When the judge asked him why he wasn't forthcoming in his initial confession, Dominico replied, “because I'm not a rat.”43

The Podesta arrested Antonio Vittori, and he admitted to his end of the plot. As a result, the Regimento put out a warrant for Fabio’s arrest, and sent summons to Venice, which Fabio intentionally ignored. Eventually the trial was postponed, and after the Malvasia and Pepoli made an uneasy peace the charges were dropped and Fabio was acquitted.44

From Vicenza with Love

While in the Veneto, Fabio got introduced to Venetian society, where he became acquainted with the illustrious widow; Lucrezia Gonzaga Manfrone, and his father’s old captain and dear friend Girolamo Martinengo; who was acting as the Governor of Verona at the time. Martinengo’s opulent palazzo45 would—again—serve as the the location for Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s 1572, Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre.46

The Venetian captain, Martinengo was no stranger to feuds, in 1533, at the head of 16 armed men, he attacked his cousin Scipione Martinengo della Motella; who murdered Girolamo’s father in 1529, and defeated his cousin’s 40 man retinue, saving his fratricidal cousin for last—so he could savor the execution.47

The widow, Manfrone, was a victim of violence of another sort. Her abusive husband, Giampolo Manfrone, was a real piece of shit, but he got his in 1544 when he impetuously tried to murder Lucrezia’s sister and her new husband; Ercole II d’Este, with poisoned candied fruit, but failed, and was eventually apprehended in July of 1546. His death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment at Lucrezia’s behest, and he died a raving lunatic in the the tower of San Michele in the Estense Castle.48

While Lucrezia’s model of human excrement husband was interred, she went about becoming a cultural icon in the courts of 16th century Italy—rubbing elbows with famous philosophers, scientists, and thinkers everywhere she went, and became a famous thinker in her own right.49 It wasn’t the alluring figure of Lucrezia that caught Fabio’s eye however, it was her daughters: Isabella and Eleonora.

Fabio started courting Isabella, and they wed in 1565.50 Isabella Manfrone was no stranger to Bologna, or the old Bentivogleschi order. Through her mother Lucrezia, she was a descendent of Giovanni II Bentivoglio, through his son Annibale II Bentivoglio, who; with his wife Lucrezia d’Este, had Emilia Camilia.51 When Emilia came of age, she married Pirro Gonzaga; brother of Luigi “Rodomonte” Gonzaga (Viggiani’s muse), who was the son of Gianfrancesco Gonzaga and Antonia dal Balzo. Emilia and Pirro had Lucrezia, the widowed mother of Isabella. The astute reader will have picked up on the big ol’Bentivoglio circle that formed in the family tree after this union, but as circles go—in family trees—this one is considerably distant enough to be deemed acceptable even by modern standards.

Fabio returned to Bologna with his betrothed, Isabella, and his mother-in-law, Lucrezia; who he introduced to Giovanni Rossi; the ex-pat Venetian printer, and Luigi Groto.52 It seems that Fabio’s time in Vicenza and the allure of his beautiful bride had coaxed him into a more stately existence. Proof of this is highlighted by an event that occurred a year after their marriage in 1566, when Fabio was 28—which would change the trajectory of the Pepoli family for the next 100 years.

Luigi “Aloisio” Pepoli: the Apple Doesn’t Fall Far

Luigi Pepoli, known as Alessio, was the bastard son of Conte Guido Pepoli and the beautiful Isotta detta la Baia, the wife of Giovanni Salazar; known as Stanghetta, who was the administrator of the Pepoli estates.53 When Guido died, care and responsibility for young Luigi was assumed by Giovanni Pepoli; who did his best to afford his nephew a stately education in subjects like literature, grammar, rhetoric, and music.54

Unfortunately, Luigi was a poor student, and a bit of a problem child, preferring to spend his time instead with the servants of the household; the stewards, the carver of the table, the valets, the coachman, and a number of stable boys.55 This certainly made sense for a boy whose parents were of a similar station; Luigi was seven when he was taken in by Conte Guido56, and had spent most of his early youth playing with kids of this class and distinction, but this reality did little to temper the disappointment of his uncles who wanted him to act like a Pepoli. In due course, this class transient nature would prove to be a trait that would characterize the rest of his life—for better or worse.

To curb this unbecoming behavior, Giovanni took young Luigi to Rome, where he hoped the influence of the Cardinal Sant’Angelo would convince the boy to take up the vocation. When Luigi realized what was going on—that he was being admitted to become a prelate—he escaped the confines of the Vatican, and returned to Bologna, 383 km on foot.57 Then, in spite of his uncle’s wishes, Luigi made the rash decision to enlist in a company of soldiers heading to Malta; most likely under the banner of Ascanio della Corgna—in 1565.58

Luigi, who was still only 19, returned to Rome from Malta sick, penniless and psychologically broken.59 Plagued by the horror of the rolling cacophony of Ottoman cannonade, and the shrill war cries of the fearsome Janissary, he had nowhere else to turn, but his uncle Giovanni. Fortunately, Giovanni was still in Rome, dealing with a dispute with the Bolognese Assunti over property that had long been in the estate of the Pepoli family, and like the father of the prodigal son he lovingly welcomed Luigi into his home and nursed him back to health.60

While Luigi learned to internalize the trauma of Malta, his uncle continued to fight his own battle in the courts of the Curia. The Assunti was an elected body of officials that adjudicated disputes to, “defend and preserve all things, rights and public jurisdictions held, possessed and occupied by any individual or by a municipality, college or university, whether temporal or ecclesiastical,” (Toselli, pg. 29) deemed necessary to the conduct of the Bolognese civic authority.61 They had the power to preserve and repossess, and in this case they chose to target two large Pepoli estates, and a factory attached to San Petronio.62

The presiding members of the Assunti were: Ercole Bentivoglio, Cavalieri Casali, Giovanni Aldrovandi, Filippo Carlo Ghisilieri, and—Cornelio ‘Quaranta’ Malvasia. Court records indicate that discussions between Giovanni and the presiding members of the Assunti were fruitful and respectful.63 Compromises were being reached, but the primary antagonist complicating the entire affair was unsurprisingly Quaranta Malvasia; whose case was strengthened by the legal advice of his brother Antongaleazzo Malvasia.64

While Giovanni was putting on the mask of civil and stately authority during the proceedings, we can imagine he let his frustration show when he got back to the Pepoli Palazzo in Rome. Luigi would have likely just sat and listened to his uncle opine about the perceived injustices, while connecting them to his memories as an 11 year-old child, watching his friends; the valets, the coachmen, and the stable boys, get taken from the Palazzo Pepoli Con Grande in chains to be interrogated and tortured at the behest of Quaranta Malvasia, and the corrupt government that had robbed his cousin Fabio in 1558.

In the end Giovanni conceded, he had no other course of action—Malvasia had won yet again.65 The forlorn uncle and his traumatized charge headed back to Bologna in silence. Luigi surely remembered the long road home, that intrepid walk inspired by his youthful ignorance and rebellious spirit, which took him to the depths of Hell, only to receive grace and compassion in his darkest hour from a man he was only now beginning to understand.

When they made it back to Bologna, in early 1566, word reached Luigi that Baldassare Rangoni, the son of the illustrious late Conte Guido II Rangoni, was mustering soldiers on behalf of Duke Alphonso II d’Este to repel the Ottoman forces threatening Hungary.66 Despite the nightmares of Malta still plaguing his dreams, Luigi longed for the comradely of combat; as only a soldier can understand, and on this account was one of the first to volunteer.

Baldassare, whose father dueled Giovanni and Guido Pepoli’s uncle in 1516, knew the young lad and his family quite well—they were thrice cousins.67 So before he gave the go-ahead to Luigi, he consulted with Giovanni, who understandably gave his blessing.68 Luigi went to Spilamberto, where he trained in the style of the late great fencing master of Modena, Achille Marozzo, who had tutored Baldassare in his youth.69 Then, as more recruits for the militia poured in, he began to help drill the rank and file.70

Luigi became not only an integral part of Baldassare’s burgeoning militia but his household as well. His predilection toward respecting not only the family, but the household staff and servants of all stations endeared him to the Rangoni, and the soldiers in his command.

As the intrepid voyage drew near, Luigi took some time to return to Bologna to say goodbye to his sister; who was a nun in the convent of San Lorenzo, and pay his respects to his uncles. Giovanni was proud of the man that Luigi had become, and in honor of his venture gave him a bay warhorse called the Turk, and 100 gold ducats. Not to be outdone, his uncle Cornelio also gave him a beautiful bay charger named the German, and another 100 gold ducats.71 The bastard boy who had fled his birthright had finally become a Pepoli in more than name. He left Bologna in tears.72

When the orders to march had been given, Baldassare locked down Castello Spilamberto to prevent desertions—as one did in that age. The orders were that no-one was to leave the Castello for any reason, but Luigi was lodged in Rocca Rangoni with the captain and his family, and he had one last piece of unfinished business to take care of before they departed, so asked his host for permission to leave with the promise of returning the next morning, a request which Baldassare respectfully granted.73

So, on the penultimate night of their departure, August 11th, he donned his mail coat, buckled his sword and a stiletto to his waist; concealed beneath a cloak, then tucked a mask into his saddle bag and rode off for Bologna.74

He was going to kill Quaranta Malvasia.

A quick note on the legality of wearing masks in the city of Bologna:

A city ordinance dated 24 September 1472 reads, “It is forbidden to carry any kind of weapons when one is masked and disguised, and anyone found with weapons can be freely and without penalty killed by any person both by day and by night. The same for those masked people who, by force, by day or by night, want to enter a house with weapons or without weapons; ordering the Podestà that he cannot bring charges against anyone who kills or wounds masked people.” (Guidicini; Via Santo Stefano)

Luigi arrived at Palazzo Malvasia, along Strada Maggiore, and thought he recognized the villain Quaranta walking with four friends beneath the palatial porticos.75 He pulled the mask from his saddlebag, and put it on, then crept to one of the pillars, and leapt on his prey, driving his stiletto into Malvasia’s back, shouting, “I have taken revenge.”76

The man who he had stabbed was not Quaranta, but Giovanni Battista Malvasia, who exclaimed, “but I have offended no one,” as he fell to mosaic floor of the portico—nearly dead.77

Luigi threw off his cloak and fled, with Cesare Malvasia; a famous knight and member of Cavalieri della Viola78, in hot pursuit. Alas, the knight was unable to catch the assassin before he mounted his horse, and thundered down the Via Strada Maggiore toward Palazzo Pepoli Con Grande.79

Upon entering the Palazzo, breathless and covered in sweat, Luigi went to talk to Count Romeo, but could only his wife Giulia, and their children; Gulio, Nicola, Ludovico and Madelana, playing with the families chancellor; who was in the middle of a silly song for the amusement of the children. When Gulia saw Luigi, armed and armored—in a frantic; desperate state, her laughter died, and she got up to reproach him.80

When she drew near, her face covered in concern, he told her that he needed to speak to the count immediately, but she quickly rebuffed his request, informing him that her husband had gone to the bathes and couldn't be disturbed.

“What is it?” she asked.

“I have caused a great disturbance,” Luigi confessed, “I have killed Quaranta Malvasia.”81

Gulias heart sank. She demanded that Luigi leave at once—this could spell the ruin of their family—and called on the valets to lock down the palazzo.82 Luigi left with his servants Fulvio and Boccale, who went to the stables where they had hidden some rope ladders, and helped him doff his armor before they rode for the San Mammolo gate, with the bells of the campanaccio ringing in the distance behind them. It was too late to escape on horseback, so they abandoned their mounts, scaled the walls of the city, and fled into the contado on foot.83

Court records indicate what happened next. The trio stopped at an inn, and asked for a guide to take them through Sasso to Castiglione, posing as students.84 A man named Dominico detta Mingone agreed to take them, and he provided the following account of the trio: “In the company, was a young man {Luigi} with the first down on his face, who was rather stout and of medium height. He was wearing a white jacket and had a pair of leather stockings (that was what they called deer skin {boots}) bordered with white silk across the top. Fulvio, whose surname is not noted in the trial, was bearded, rather large than otherwise, had long blue cloth stockings, blue scoffoni, and a thin white canvas jacket. While Boccale was rather small; he had a London felt hat with a band of the aforementioned hat turned upside down, and was dressed in black.” (Toselli, pg. 33)

They stopped in Raggazzone, at the home of Lodovica Rossi, where Luigi sent Boccale back to Bologna to retrieve he and Fulvio’s armor, while the pair followed Mignone through Sasso. They stopped in Murazzo Della Budelle so Fulvio could rest, then continued their journey, until they reached the ancestral lands of the Pepoli. Once in Castiglione they departed from their guide and made their way to the castle, where Luigi asked the guards to summon his cousin. 85

Fabio Pepoli met Luigi at the gates of Castello Castiglione, and once he had raveled the reason for his visit—as much as it painted him to do so—turned him away. He couldn't be implicated in another attempted assassination on Quaranta Malvasia after he'd just been cleared of the same charges— Luigi was on his own.86

In November of 1566 Luigi was summoned to trial, but ignored the summons—as per tradition—and on account of his absence was exiled from the territory of Bologna; under the penalty of death in the case of contravention. Giovanni was interrogated and forced to testify, but was acquitted of any wrong doing.87

Of note, many of amazing details of this story come from Giovanni’s testimony, and fellow witnesses involved in the investigation.

The story will continue in Part 2, with Fabio’s transition into the good graces of Bolognese civil society. In 1569, he joins Vincenzo Legnano, and Pirro III Malvezzi (both Knights of Viola) on a crusade to take down the heretic French Huguenots. Then doubles down on his commitment by joining the War of Candia, with his cousin Alessio in tow, and takes part in the famous Battle of Lepanto. As Giovanni notes in his introduction, Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre is inclined to the virtue of the military art, and both of these campaigns predate the publication of dall’Agocchie’s work. You won't want to miss it!

If you'd like to continue to follow the incredible story of Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s patron, Fabio Pepoli, be sure to subscribe—its free. If you'd like to support us financially, we'd be grateful. All proceeds go toward funding our research. If you'd like an alternative means of supporting our efforts, check out our webstore!

Works Cited:

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume Italy, Rossi, 1608. Digital.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo II (1500-1521). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital.

A Companion to Medieval and Renaissance Bologna. Netherlands, Brill, 2017.

Racconti storici estratti dall'archivio criminale di Bologna ad illustrazione della storia patria per cura di Ottavio Mazzoni Toselli: 1. Italy, pei tipi di A. Chierici, 1866.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Guglielmotti, Alberto. Marcantonio Colonna alla battaglia di Lepanto per il p. Alberto Guglielmotti. Italy, F. Le Monnier, 1862.

Cronologia delle famiglie nobili di Bologna con le loro insegne, e nel fine i cimieri. Centuria prima, con vn breue discorso della medesima citta di Pompeo Scipione Dolfi ... - In Bologna : presso Gio. Battista Ferroni, 1670. Biblioteca Dell’Archiginnasio. badigit.comune.bologna.it/books/dolfi/scorri_big.asp?Id=615. Digital.

Gozzadini, Giovanni. Giovanni Pepoli e Sisto V.: racconto storico. Italy, Presso N. Zanichelli, 1879.

Mazzoni Toselli, Ottavio. Racconti storici estratti dall'archivio criminale di Bologna: ad illustrazione della storia patria. Italy, A. Chierici, 1866.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Count | Titles of Nobility and Royalty in Europe.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 July 1998, www.britannica.com/topic/count.

Il “Castellaccio” Di Castiglione – Centro Di Cultura Paolo Guidotti Di Castiglione Dei Pepoli. www.centroguidotti.com/sala_delle_origini/il-castellaccio-di-castiglione.

Lelli, Marcello. CASTIGLIONE dei Pepoli; Enciclopedia Italiana (1931). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/castiglione-dei-pepoli_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/. Accessed 11/6/2024. Web.

Armstrong, Edward. The Emperor Charles V. Contributor, Robarts - University of Toronto, vol. 1, London: Macmillan, 1910, archive.org/details/emperorcharlesv01armsuoft/page/n7/mode/2up. Digital.

Damiani, Roberto. Girolamo Pepoli. Condottiereventura.it. https://condottieridiventura.it/girolamo-pepoli-conte/. Accessed 12/10/2024. Digital.

Benzoni, Gino. MARTINENGO, Girolamo; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 71 (2008). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/girolamo-martinengo_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Web.

Ridolfi, Roberta Monica. GONZAGA, Lucrezia; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 57 (2001). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/lucrezia-gonzaga_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Web.

Swanger, Jherek. Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Dell’Arte di Scrimia, “The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation”, lulu press, May 5, 2018. PDF.

López-Guadalupe Pallarés, Miguel José. Redes Y Estrategias de Ascenso En La Monarquía Hispánica. La Familia Malvezzi Y El Colegio de España En Bolonia (Siglos XV-XVI). 1st ed, Dykinson, S.L., 2023.

Wood, James B.. The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society During the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-76. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Boltanski, Ariane. « Forging the “Christian soldier.” The Catholic supervision of the papal and royal troops in France in 1568-1569 ». Revue historique, 2014/1 No 669, 2014. p.51-85. CAIRN.INFO, shs.cairn.info/journal-revue-historique-2014-1-page-51?lang=en.

Gigon, Stéphane Claude. La troisième guerre de religion: Jarnac-Moncontour (1568-1569). France, Henri Charles Lavauzelle, 1909.

Delage, Franck. La Troisième Guerre De Religion En Limousin : Combat De La Roche-l’Abeille, 1569. Desvilles (Limoges), 1950. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Philosophie, histoire, sciences de l'homme, 2017-255509. gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3407745q#. Digital

Wandruszka, Nikolai. Un viaggio nel passato europeo—gli antenati del Marchese Antonio Amorini Bolognini (1767-1845) e sua moglie, la Contessa Marianna Ranuzzi (1771-1848): Pepoli (I-V) inkl. de Pizzigotis. 2012-2018. PDF.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Count | Titles of Nobility and Royalty in Europe.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 July 1998.

Italy

With the decay of Carolingian authority, a system of countships based on cities grew up in Italy. Probably none were dependent on dukes, the ducal title being then comparatively rare, especially in northern Italy. The rise of communes meant the end of the countship’s former significance, but as a mark of privilege, the title of count was quite liberally bestowed by the popes and other sovereigns of the peninsula well into modern times.

Il “Castellaccio” Di Castiglione – Centro Di Cultura Paolo Guidotti Di Castiglione Dei Pepoli.

Nel 1340 Giacomo e Giovanni figli di Taddeo Pepoli, già signore di Bologna, acquistarono dal conte Ubaldino degli Alberti di Mangona il castello di Castiglione dei Gatti, la terza parte della villa di Baragazza (la zona rurale circostante il castello), la sesta parte della villa di Bruscoli e la terza parte di quel castello, oltre a 72 poderi, luoghi sui quali potevano esercitare la “giurisdizione di mero e misto imperio”.

Il “Castellaccio” Di Castiglione – Centro Di Cultura Paolo Guidotti Di Castiglione Dei Pepoli.

Tale acquisto venne ratificato nel 1369 dal diploma dell’imperatore Carlo IV, che concesse ai Pepoli l’investitura feudale. Nonostante l’acquisto e l’investitura, Baragazza rimaneva in mano a Bologna, che nel 1365 stipendiava i conti Alberti di Bruscoli per la sua custodia. Negli anni seguenti Guidinello degli Alberti di Mangona spadroneggiava nel castiglionese, asserragliato nel “Castellaccio” e nel vicino castello di Civitella. Nel 1383 il fiero conte, con il consenso di Firenze, stipulò patti con Bologna in castro Castiglionis Gatti in pallatio habitationis dicti Guidinelli, ossia nel palazzo esistente dentro il castello, cosa che fa supporre che l’area interna alle mura dovesse essere alquanto vasta, tanto da contenere un edificio di dimensioni e fattezze non trascurabili (pallatio).

Il “Castellaccio” Di Castiglione – Centro Di Cultura Paolo Guidotti Di Castiglione Dei Pepoli.

Nel 1390 Guidinello venne bandito dal territorio bolognese, condannato al taglio della testa e tutti i suoi beni vennero confiscati. Il castello di Castiglione passò nelle mani di Bologna, che lo fece atterrare. Nonostante la condanna, nel 1394, il Comune di Bologna fu costretto a venire a patti con Guidinello e a versargli 2.500 fiorini a titolo d’indennizzo per la requisizione dei suoi beni e del “Castellaccio”.

Damiani, Roberto. Girolamo Pepoli. Condottiereventura.it. Reference; 1523. Digital.

Fa parte a Bologna della Magistratura dei Gonfalonieri. Nemico di Melchiorre Ramazzotto, cerca di diminuirne l’autorità nella città con la proposta dell’ abolizione delle contee, istituite dal papa Leone X, che smembrano l’unità del territorio comunale. E’ inviato a Roma per difendere il progetto presso il papa Adriano VI.

Wandruszka; IX.802, pg. 3

Per alcune notti Girolamo Pepoli incita i bolognesi ad ammazzare di notte quanti più spagnoli trovino indifesi per le strade: i cadaveri sono gettati nelle fogne e nei pozzi, pochi sono quelli abbandonati sulle strade; e' inviato dal papa alla guardia di Pistoia: ha con sé molti soldati con i quali ha il compito di mantenere l'ordine pubblico, scosso giornalmente da inconvenienti vari e da tumulti(.)

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 2.

In quel tempo fi parti di Bologna Vber- to Gambara Vicelegato , & andò al Pontefice , che lo mandò Nuntio all'Imperatore in Germania , hauendo egli lafciato per fuo Luogotenete Bernardino Caftellario detto dalla Barba Vefcouo di Cafale di Monferrato , huomo di grande ingegno , & ardito affai , & che cercò di opprimere quei gentil'huomini , che paruero à lui di trop pa autorità ; frà quali furono alcuni della famiglia de i Pepoli , i quali , per non hauere à incorrere in qualche peri- colofo trauaglio , conofcendo di hauere poco amico il fuperiore , fi partirono di Bologna , & fi ritirarono à i luo- ghi , & alle Città vicine , paffando il tempo con manco fa ftidio che foffe poffibile , fin che duraffe la pericolofa bo rafca , la quale non perfeuerò molto lungamente , perciò- 1531 che nell'anno feguente , che fu il Mill'e cinquecento tren ta vno , mentre tutte l'altre cofe paffauano tranquilla- mente , ſenza veruno auenimento notabile , tornò nel gouerno Vberto Gambara , il quale fi era fpedito dalla fua Nuntiatura ; & ne haueua già renduto conto al Pontefice in Roma ; & Bernardino dalla Barba fuo Luogotenente fi partì di Bologna , & andoffene à Roma .

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 2.

Ma per pochi giorni fi fermò in Bologna il Veſcouo Gambara , perche il Pontefice madò in cambio di lui per Vicelegato Fran cefco Guicciardini Fiorentino huomo , che haueua mo- glie , & figliuoli , & era letterato , & intendente affai ; co- me moſtrano le fue hiftorie , & l'altre cofe fcritte da lui dottamente : & quefto fù il primo , & forſe folo , che mai , non effendo prelato , foffe da ' Pontefici mandato à gouer nare la Città di Bologna.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 3.

Sotto il gouerno di queſt'huo mo fù dato da Bolognefi à i Frati di San Francefco di Paula la Chiefa di San Benedetto nella ftrada di Galie- ra ; come anco fù dato à i Canonici Regolari di San Gior gio di Alica la Chieſa di San Siro , & il gualto de'Ghifilieri , nel quale cominciarono la fabrica , & il conuento di San Gregorio nell'anno che feguì nel principio del qua- 1532 le Papa Clemente con poca fodisfattione di alcuni Ġen til'huomini particolari , riuocò con vn fuo breue le gratie à loro fatte già da Papa Leone Decimo , il quale quando in Bologna fi trouò à parlamento con Francefco Rè di Frácia , gli haueua creati Cõte , afſegnado loro có danno del comune alcuni luoghi del contato ſotto titolo di par ticolar Contea . Frà quefti furono Lattantio Felicini Conte della Barifella ; Giouan Franceſco Iſolani di Mi- nerbio ; Andrea Cafali di Mongiorgio , Lodouico Goza- dini di Liano ; Antonio Volta di Vico , & Verzano ; Mel- chiore Manzuoli di San Martino in Souerzoni ; Galeaz- zo Caſtelli di Beluedere , & Serraualle ; Camillo Goza- dini di Zapolino ; Vincenzo Hercolani delle Riuazze ; Agamennone Grafsi di Labante ; Nicolò Lodouifi di Sa- moggia ; Lodouico Caldarini di Cafola , & Cironi ; Mino Rofsi di Pontecchio ; & Ouidio Bargellini di Bargio , & Badi .

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 3.

Et non ſolamente i particolari à quel tempo fenti- rono diſguſto ; ma tutto il popolo ancora hebbe traua- glio , percioche Papa Clemente di continuo intricato nella guerra , era molte volte intento à cauar denari da i popoli foggetti alla Sede Apoftolica , & particolar- mente dal Clero ; & per tal'effetto haueua egli mandato vn certo Vincenzo Cauina perfona , che fenza rifguardo hauere à veruno , riſcoffe due decime di tutte l'entrate de i beni Ecclefiaftici. Et haueua parimente il Pontefice co- mandato , che i Bolognefi pagaffero vn ducato d'oro per ciaſcuna famiglia , & per ciaſcuna caſa ; ma hauendo eſsi fatto fignificare al Pontefice , che quando non fi voleffe piegare à qualche fopportabile accordo , la cofa portaua feco molte difficoltà , & forfe ancora pericolo di alcun tumulto popolare(.)

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 4.

(S)i contentò che gli foffero pagati dicidottomilla fcudi per quella impofitione ; onde il Se- nato fece vn partimento , accioche ciaſcuno pagaffe vna certa portione della grauezza ; ma parendo al popolo mi nuto , che la taffa non foffe partita giuftamente , & che molti foffero aggrauati più di quello , che loro pareua conueneuole , fi folleuarono alcuni plebei , & entrando im petuofamente in Palazzo à parlare al Confaloniero di Giuftitia , fecero querella d'ingiufto partimento , & ven- nero à tai conteſe con effo Confaloniero , che poco vi mancò , che non occorreffe alcun difordine , ma ciò inten- dendo i Tribuni della Plebe fi mifero di mezo pigliando effi la cura di fare vn nuouo , & giufto partimento , con fo disfattione di tutti ; & così reſtò acchetato il rumore .

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 4.

Ma non fù già così ageuolmente , & fenza violenza rafre nata la temerità di Camillo Sacchi huomo di gran ſegui to nelle montagne di Bologna , il quale teneua grande- mente infeftato il paefe di Vergato , & altri luoghi , & vil le della montagna , doue il Guicciardini Gouernatore fù forzato à mandare Melchiore di Ramazzotto con tre- cento fanti , i quali abbrugiarono effo Sacchi dentro ad vna cafa , ammazzando tutti i fuoi compagni , & feguaci , & facendone alcuni prigioni , i quali poi fecondo i meri- ti loro furono caftigati dalla giuftitia con l ' vltimo fupplicio .

Rebecchini, Guido. “Rituals of Justice and the Construction of Space in Sixteenth-Century Rome.” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 2013, pp. 153–79. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.1086/673419. Accessed 7 Dec. 2024.

On March 14, 1534, Giuliano Cesarini, the head of one of the most illustrious and ancient Roman families, stormed the city on horseback with some companions and attacked the papal governor, Gregorio Magalotti. After chasing Magalotti briefly through the streets of the city center, Cesarini finally cut off Magalotti’s right hand in front of the Pantheon. Magalotti had been made Governor of Rome by Clement VII in 1532, with the specific task of enforcing a ban on weapons on the inhabitants of Rome, regardless of their status and privileges. As the sentences that he issued testify, he was an extremely rigorous magistrate, and, in complying with his duties, just a few days before the assault Magalotti and the bargello (the head of the police) had dared to search Cesarini for weapons in public. Cesarini considered this to be outrageous, “especially since he was a Roman baron and the gonfalonier of the Roman people,” as a foreign agent reported.25 Cesarini clearly felt that his status and role granted him a position of privilege and exemption from ordinary legislation, and this assumption led him to perceive the attempt by those vested with papal authority to impose control on him as an attack on his personal honor and class rights that required an adequate and swift reaction. Immediately after the assault, Cesarini fled the city and took refuge at Marino, in the lands of the Colonna family, another baronial family that was very jealous of preserving its autonomous power. As a response to this attack, the enraged Pope Clement VII ordered that a defamatory painting of Cesarini hanging by his feet be displayed outside the Senator’s palace on the Campidoglio. This form of punishment, well documented throughout the Middle Ages, was usually reserved for traitors and was meant to symbolically annihilate the very humanity of the figure represented by turning him upside down, as can be seen, for example, in a series of drawings by Andrea del Sarto dating from 1529 to 1530.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 4-5.

In quel tempo Solimano gran Signore della Turchia con vn potentifsimo effercito ; fecondo che riferisco no molti fcrittori ; di trecentomilla combattenti , e tren- tamilla guaftatori , entrò nell ' Ongheria per foggiogarla ; & poi nell'Auftria , doue fermò il campo preffo alla Città di Vienna ; ma perche vi fi trouò in perfona Carlo Im peratore , che con vn fioritifsimo effercito di ottantamil- la fanti , e trentamilla caualli tutti foldati eletti animo- famente fe gli oppoſe , fù forzato il Turco à ritirarfi con perdita di vna gran parte delle fue genti , le quali reftarono morte di pefte , & di difagio in quei paefi : onde tro ~ uandofi lo Imperatore libero da quella guerra , & hauen- do à fare alcuni ragionamenti , per beneficio del Chri- ftianefimo col Pontefice , volfe tornando da Vienna ve- nire in Italia ad abboccarfi con effo Pontefice ; il quale hauendo determinato che il luogo dello abboccamento fofle Bologna , ordinò , che fi metteffero in punto tutte le cofe neceffarie per gli alloggiamenti : & poi accompa gnato da quattordeci Cardinali , con diciotto Vefcoui , & altri Prelati fenza gran pompa , del Meſe di Decem- bre arriuò in Bologna ; & alloggiato nel publico Palaz zo , aſpettò lo Imperatore , il quale poco dopo nel giorno di Santa Lucia giunfe anco egli accompagnato dal Du . ca di Milano ; Duca di Matoua ; Aleffandro de'Medici fat to nuouamente Duca della República Fiorentina ; dal Duca d'Alua ; dal Marchefe del Guaſto , & da molti altri Prencipi , & Baroni che tutti agiatamente furono allog- giati nelle cafe de i cittadini.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 5.

(M)a la maggior parte de i foldati di Cefare , che quafi tutti erano Tedeſchi , furono compartiti , & alloggiati fuori della Città ; ma poco lontani dalle mura , che così volle to Imperatore , accioche fi leuaffe l'occafione , che fi haueffero à rinouare le conte- fe , & le riffe nate già l'altra volta quando la corte fù à Bologna , frà i Cittadini , & alcuni de'fuoi foldati , i qua- li per le male fodisfattioni , che l'vna parte haueua dell'altra , facilmente ſi ſarebbono di nuouo attaccati à queſtionare infi eme .

Armstrong, Edward. The Emperor Charles V. Contributor, Robarts - University of Toronto. vol. 1. London: Macmillan, 1910.

The house of Gonzaga had Imperial traditions and these Charles encouraged by every means. He erected the marquisate into a duchy, and allowed its ruler to marry the heiress of Montferrat. When the lord of Montferrat died (1533), Charles invested Gonzaga with the marquisate, in spite of his brother Ferdinand's eagerness to possess it. The little state, wedged in between Milan and Piedmont, with its strong: fortress of Casale, might prove very valuable in friendly hands. The heir to Mantua was linked to the Habsburgs by marriage with Ferdinand's daughter, while Charles heaped benefits upon the duke's brother, Ferrante Gonzaga, his foremost general and personal friend, who in 1535 became viceroy of Sicily.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 7.

Et con tranquillità ſi paſsò ancora vna buona parte dell'anno Mill'e cinque 1534 centotrentaquattro , fin tato che intefofi come il Papa in Roma era grauemente malato , & in pericolo di morte , il Senato col confenfo del Legato affoldò nouecento fan ti per guardia così della piazza , e del palazzo , come del- le porte della città , accioche non fi haueffe da incorrere in qualche difordine , ò tumulto(.)

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 7.

Et con tranquillità ſi paſsò ancora vna buona parte dell'anno Mill'e cinque 1534 centotrentaquattro , fin tato che intefofi come il Papa in Roma era grauemente malato , & in pericolo di morte , il Senato col confenfo del Legato affoldò nouecento fan ti per guardia così della piazza , e del palazzo , come delle porte della città , accioche non fi haueffe da incorrere in qualche difordine , ò tumulto , quando fi publicaffe la morte del Papa , la quale ſi aſpettaua d'hora in hora , poi- che per l'hidropifia , & per altre infermità, che à poco à poco lo andauano confumando , fi teneua per ifpedito il fatto fuo ; & à pena fi era finito di fare la prouifione dei foldati in Bologna , che s'inteſe la morte di lui . Morto Papa Clemente il Guicciardini fi volfe ritirare da i ma . neggi del gouerno , perche dubitò che i Cittadini ricufaffero di vbidirlo , poiche non haueuano più timore di Papa Clemente :

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 7.

(M)a i Senatori , hauendo confiderato che quando Bologna foſſe reſtata ſenza gouernatore in tem- po di Sede vacante , poteuano auuenire molti difordini , lo pregarono , che non abbandonaffe la cura del gouer- no , offerendogli ogni aiuto poffibile , & il fauor loro in tutte le cofe , & principalmente contra coloro , i quali prefumeflero di voler turbare la pace , & la tranquil- Îità de ' Cittadini ; & perciò feguitò egli nel gouerno prouedendo à tutte le occorrenze al meglio che fu poffibile.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 7-8.

E perciò feguitò egli nel gouerno prouedendo à tutte le occorrenze al meglio che fu pof- fibile : ma molti gentil'huomini mal fodisfatti di lui ne faceuano poca ftima ; & frà gli altri Galeazzo Caftelli , & Gieronimo Pepoli , che ritirati ne gli anni à dietro da Bo logna , n'erano ftati abfenti fino à quell'hora ; perche fapeuano che il Guicciardini poco gli amaua; quando in tefero della Sede vacante deliberarono di tornare alle cafe loro , moftrando di tener poco conto di lui: E perciò amendue inſieme accompagnati da molti amici armati ; frà quali erano alcuni banditi ; di mezo giorno en- trarono in Bologna ; doue furono con liete accoglienze riceuuti, & vifitati da i loro amici ; la qual cofa difpiac- que affai al Guicciardini , parendo à lui , che ciò fi faceffe in fuo difpregio :

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 8.

E mentre ch'egli ftaua con defiderio di farne alcun rifentimento , fe gli prefentò l'occafione ap punto , come voleua ; percioche occorfe , che vna notte due banditi di pena capitale andando per la città furono trouati da'sbirri , & menati nelle prigioni , & intenden- do il Guicciardini , ch'efsi erano amici de i Pepoli , fubi- to ſenza cercare altra cofa comandò che foffero fatti morire(.)

Wandruszka; IX.802, pg. 3

Girolamo Pepoli, compagnato da molti fautori, si dirige verso il palazzo dove alloggia il governatore; è raggiunto in via delle Chiavature da alcuni senatori che lo convincono a desistere dai suoi propositi.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608. Pg. 8.

(P)er la qual cofa hauendone prefo graue fdegno il Conte Gieronimo Pepoli accompagnato da molti ami- ci , vícì di cafa per andare à trouare il Guicciardini , & ri- fentirfi dell'offefa , che gli pareua di hauer riceuuto , & arriuato à punto in capo della via detta delle Chiauatu- re , haueua già quafi meffo il piede sù la piazza maggio- re , quando hauendo il Senato intefo quel mouimento , mando alcuni Senatori ad effortar Gieronimo , che non voleffe dare occafione di tumulto al popolo , e che fi con . tentaffe per conferuatione della quiete publica di torna- re à cafa : onde egli non volendo difpiacere à i Senatori tornò in dietro co ' ſuoi amici .

Fletcher, Catherine (2020). The Black Prince of Florence: The Spectacular Life and Treacherous World of Alessandro de' Medici. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pg.

Damiani, Roberto. Girolamo Pepoli. Condottiereventura.it. Reference; April 1537. Digital.

Favorisce Filippo Strozzi ai danni del duca di Firenze Cosimo dei Medici; rifornisce di vettovaglie i fuoriusciti. Per questo fatto è nuovamente diffidato dal cardinale Guido Ascanio Sforza. I soldati da lui arruolati nella circostanza sono sollecitati a restituire il soldo percepito.

Wandruszka; IX. 802, pg. 3.

1537 Lorenzino dei Medici uccide a Firenze il duca Alessandro dei Medici. Prima di raggiungere Venezia, si ferma a Bologna dove si trovano molti fuoriusciti fiorentini. Costoro si preparano a rientrate in Toscana.

Wandruszka; IX. 802, pg. 3.

Interviene il legato apostolico della città, il cardinale di Santa Fiora Guido Ascanio Sforza, che lo convince a desistere dal proposito

Toselli, pg. 34

Correva l'anno 1558 che il conte F*** preso servizio negli eserciti veneziani fece venire in Bologna due soldati vicentini ; l'uno era chiamato Orazio , dell'altro non è scritto il nome : il primo era giovane grande di bella vita , con barba rossa tonda ; vestiva un par di calze gialle intere im- braccate di velluto , un colletto bianco , cappa ne- ra , stivali bianchi , e beretta di velluto . L'altro alquanto più bassotto di mezzo tempo aveva barba nera , e vestiva di nero senza cappa . Era il deci- moquinto giorno di marzo , che il conte F*** chia- mato a se messer Giacomo suo mastro di casa e i due soldati comando loro di uccidere il Malvasia , poi parti subito per Venezia .

You’ll notice that Fabio’s name is redacted through most of Toselli’s collection. This is on account of his name being stricken from the record during and after the court preceding’s. Gozzadini confirms his identity:

Gozzadini, pg. 31

Risalendo il torrente Setta , Aloisio giunse al montano Castiglione , feudo dei Pepoli , di cui avrò a parlare e presentossi all ' altro zio - cugino conte Fabio , che nel proprio castello era confinato non so per qual cagione . Ma anche costui negd ascolto e ricetto ad Aloisio e lo scaccid per non dar sospetto di complicità , imperciocchè otto anni prima , essendo stato ferito quel senatore Malvasia che Aloisio credeva di aver pugnalato , venne incolpato e proces- sato contumace esso conte Fabio , che poi fu assolto .

Toselli, pg. 34-35

Nel giorno 22 dello stesso mese Orazio mentre pranzava con donna Giulia madre del conte F * , e con Giacomo mastro di casa , al cocchiere che serviva alla ta- vola disse : << Oh cocchiere vorria che tu mi fa- cessi un appiacere , voglio che tu vada domattina di buon ora a casa di messer Antonio Vittori , e digli da parte mia che ti dia quel cavallo che mi ha promesso , e lo metterai qui nella stalla , che devo andare a fare un servizio .

Toselli, pg. 35

La seguente mattina a buon ora il cocchiere andò alla stalla del Vittori , ed avuto un cavallo grigio e bianco con sella e briglia , lo condusse alla stalla , ove levatagli la briglia e gettatala su l'arcione lo legd colla cavezza alla mangiatoia . In questo mentre arrivò il compagno di Orazio con un cavallo rosso , e lo attacco colle redini ad una tramezza . Vi giunse ancora Orazio a cui il socio disse è meglio che mettiate la briglia al cavallo che vogliamo andare a fare quel servizio . Orazio fece ciò che gli disse il compagno , poi partirono dalla stalla(.)

Today Via Clavature: https://www.originebologna.com/odonomastica/clavature-via/

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Come Chiavature questa via è ricordata in un rogito del 1377 documentato dal Guidicini1, che aggiunse anche2 che nel 1408 questa via era chiamata anche Via di San Vito (dalla vicina chiesa di Santa Tecla dei Lambertazzi o di San Vito).

Questo odonimo, con piccole insignificanti varianti (Chiavadure, Ruga delle Chiavature, Chiavadur) venne proposto dallo Zanti, e da tutti gli autori successivi fino al 1801 quando venne formalizzata con le lapidette come Clavature.