Ferrara, Italy—August, 1529

The boys came to the duel first.

They were coarse youths with patched tunics and threadbare hose. They were the kind of kids whose future held nothing but backbreaking toil or a mass grave on the site of some lost battle. By cock’s crow there were dozens of them already inside the dueling ground, jockeying for the best seats in the house, filling the air with insults and threats.

The dueling ground of Ferrara vaguely recalled the gladiatorial arenas of Rome, but only in the way that much of Italy was but a pale imitation of the ancients. Instead of the masonry palaces of blood where men fought for life and death to amuse a vast crowd, Ferrara’s was a ramshackle affair of worn wooden benches. Still, in preparation for today’s fight, the Duke’s men had given the seats fresh white paint. Soon, the early pink light of dawn cast a feint reddish glow upon the benches, like blood thinned by water, presaging the savage fight that was to happen that day.

With the coming of daybreak came servants from the noble houses, many in the two-colored livery of their houses. They came to take the best seats for their masters, knowing they would be caned for failing to find a good one. A few of the youths who had come first managed to fetch a penny for their seats, but most were driven away by menacing swings of the servant’s cudgels. Servants of rival houses glared menacingly at one another but there were no fights this morning.

The Duke’s soldiers came later, bearing the swords for the duel. They were solemn as they took these inside the barrier — the long white fence that would separate those watching from those fighting. During the duel, to cross that barrier meant execution and this leant to the men guarding the swords inside the enclosure an obvious unease.

Some eight thousand souls would watch the duel this day, from the benches or from the balconies and rooftops of the houses around the square where the fight was taking place. They first came at a trickle and then in a flood as the fight drew near until, by eleven o’clock the arena was a buzzing hive of humanity—gossiping, gambling, swearing, flirting, joking humanity.

At the cry of a trumpet this noise came to a stop and everyone inside the arena stood as their lord, Duke Alfonso d’Este entered the arena. He was a heavy, gouty man in his fifties who moved slowly through the crowd. In keeping with the spirit of the day he held a partisan in his hands, as though he himself were prepared to do battle. He took his seat inside a pavilion that offered succor from the oppressive summer sun.

That sun glittered off the freshly polished swords in the middle of the dueling ground and slowly moved the shadow along a sundial near the swords. A servant crouched over the sundial, watching the shadow move with the intensity of a hunter following his prey. Once it read eleven o’clock the servant jumped up into a position of attention.

The Duke noticed and with one nod of his head, the men in the enclosure left. An expectant sigh, a collective gasp pregnant with anticipation echoed from the thousands watching.

The two padrini, respectable gentlemen representing each fighter, entered the enclosure and placed themselves by the swords. They were both men from Bologna and rivals, if not outright enemies, and moved with the rigidity natural to men when in the presence of someone they hated.

Now the drummers went to work. On tightened war drums they beat out a tattoo, a cadence for a slow march. The sound of it reverberated through the arena, echoed off the houses, mounting in volume until it was almost like the roar of cannons on a battlefield. The drums summoned the fighters to the dueling ground.

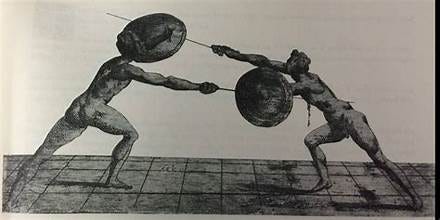

Christopher Guasco from Lombardy was the first to arrive. He was a beardless young man, tall, and of great physical beauty, certainly swoon-worthy in the drama of the moment and clearly the crowd favorite for the fight. Since he was the one challenged to the duel, the choice of arms had fallen to Guasco. He had elected to fight with swords and rotellas — round iron shields commonly used for assaulting walls, or for protecting men of note on city streets at night. For armor each man wore a breastplate, an open faced helmet along with armored gloves and a vambrace for his right forearm.

Were the fight to go for a long time, the wise thought the weight of the weapons and armor would give an advantage to the young Guasco, since he was still very much in the pink of life, with the white-hot lightning of youth flowing in his veins.

A hiss went through the crowd as the challenger of the duel, Nicholas Doria made his way into the arena and to his side of the dueling ground. In comparison to Guasco’s ruddy cheeks and lively steps, Nicholas Doria looked a sallow yellow, as though suffering a touch of jaundice. Though only a few years older than Guasco, the soldier’s life was a hard one, and Doria suffered from recurrent bouts of malarial fever that sapped his color and stamina.

This Doria, from Genoa, had not only been the one to issue the challenge to Guasco, but he was the instigator of the quarrel between the men because he had once publicly slapped Guasco like a cheeky tavern wench. This was hardly a surprise since the Genoese were known for their ill-temper. Doria’s disposition and actions were the main reason the crowd was against him, though the fact that he was uglier and shorter certainly did not help his cause.

Unlike the beardless boy, Nicholas Doria was a man in the full prime of manhood, sporting a bushy beard and strong muscles. Doria moved with efficiency and focus, like a craftsman getting ready to perform the job he has spent his life doing. He took up his side inside the barrier opposite from Guasco.

Attention now fixed upon the two padrini. Guasco’s padrino was the experienced warrior, Emilio Marescotti of Bologna, a fighter trained by the famous master of arms, Achille Marozzo. Knowing that the fight would be with the sword and the rotella, Marescotti had passed on what knowledge of the sword and rotella he had learned from his fencing master. He took up one of the swords in the middle of the dueling ground and he inspected it as the metal glowed white and flashed in the sunlight.

Doria’s padrino for the duel was Filippo Pepoli, brother of the famous warrior, Hugo Peploli.1 In a loud and formal voice Filippo Pepoli shouted, “I declare these swords free of defect and of witchcraft.”

The padrini now brought the swords to the two duelists.

The Duke’s steward spoke to the crowd to announce the rules of the duel. “If anyone breaks a weapon in this fight then he may get another, but if he drops his weapon then that is his misfortune.”

When people started to speak, he rapped the butt of a staff on a bench for silence.

“Upon the pain of death you must not speak or spit or make any sign as the duel is occurring.” His ominous tone made it clear these words were not just a formality.

Then everyone left the barrier except the two duelists. The crowd was silent and expectant, the moment tense and electric.

The First Assault

On his side of the arena Doria stood proud, his rotella shimmering in the sun before him and the sword in his left hand. On the opposite side, Guasco stood with his back turned to Doria. Was he showing contempt? Had one of the bevy of young ladies on his side caught his attention? No – he was simply following the counsel passed onto him by Emilio Marescotti – not to look at his opponent until it was time to cast the iron dice.

A loud trumpet sounded in the silent arena. Once the sound had come and vanished the Duke called out, “Be ready, gentlemen!”

With this sound Doria took the sword from his left hand and put it into his right hand.

After the second blast of the trumpet the Duke shouted, “On knights!”

Doria lifted his sword and threw a small reverse cut that alighted his sword on the right side of his body. Guasco turned now to face his opponent, letting his sword dangle down and to the right with its point facing the ground.

And finally resounded the last call, the one that began the duel. The Duke declared, “Fight!”

Doria threw a cut with his false edge and turned the rotella over his sword hand so that his body was hidden by it. Guasco struck the false edge of his sword into the face of the rotella and it rung like a country gong summoning the field hands for supper. But this gong did not ring for supper, it called for death.

The young and pretty Guasco moved elegantly to the center of the dueling ground. His feet crossed and pivoted, so that the path he took to the middle of the dueling ground undulated right and left like a serpent slithering into the battle. As Guasco came forward, he continued to play his sword against his shield, banging out the rhythm of his steps. He moved with such dancelike grace that men murmured their admiration and the ladies felt their hearts quicken and their bodices grow tight.

Unlike the elegant Guasco, Nicholas Doria went to the middle with workman-like efficiency, simply bringing one foot behind the other and then stepping in a straight line. Doria went directly at Guasco and when the two warriors came into striking distance, everyone could see that Doria had taken more than half the field.

Now at this striking range they both stood in identical armor and identical swords, eyeing one another carefully. Both were well-balanced and ready to strike. But there was one great difference in the guards in which they stood: Doria kept his rotella in the ordinary manner with its face turned directly at the enemy and his body held behind it, while Guasco kept the face looking off to his left side in the Bolognese manner so that he had an unobstructed view of his opponent, his body open and baiting Doria to strike.

Guasco stood with his left foot forward, a defensive posture. He hoped to get Doria to strike first, so he can set aside that attack and make a safe one of his own. Just as Emilio Marescotti told him to do. The better fighter waits for the opponent to attack and then pounces on him.

But of course, a practiced fighter like Doria knew this.

In all affairs of the sword time is life and distance is time; so the two men remained at the very edge of striking distance.

What ensued could hardly be seen from the stands. The experienced Doria had correctly read Doria’s guard, the tension of his neck, his enemy’s posture all as defensive and indicated a desire to receive a stroke and then make his attack. He tested Doria on this: he stepped forward a bit to force Guasco to retreat. He stamped his feet to provoke a response, he made a half thrust at Guasco, but Guasco did not attack or begin a parry. Guasco recognized Doria’s actions as an attempt to draw Guasco from his well-formed guard and refused to chomp on the bait.

But Doria’s plan was far deeper. Guasco had erred not in taking the defensive, but in being unwilling to depart from it. Doria planned to make him pay for this error, to pay in blood.

Doria kept up a series of motion to steal time from Guasco. With half thrusts and motions forward the older warrior confused the beardless youth, since Guasco could not know which attack would be the genuine article, conceding valuable reaction time to Doria.

And time is life.

Doria made two half-jabs with his sword that prompted no response from Guasco. On the third blow he shot forward with a genuine thrust. Because Guasco was assuming this was another fake, he was too slow to react when the thrust came towards his chest.

The thrust found a gap in the armor on Guasco’s front and penetrated into Guasco’s chest. Guasco gave a cry and backed off as Doria recovered back into his guard.

Then Doria stepped forward again and started a thrust on the left side like he intended to strike Guasco in the face. Guasco’s muscles tightened and his sword moved ever so slightly, now Doria’s muscle go tight as he appears ready to explode forward. The young Guasco lifted his rotella ever so slightly to cover it, and Doria starts turning the sword down like he is going to cut to Guasco’s leg.

Guasco tensed too, expecting the blow, remembering his instruction. Then Doria visibly relaxed and let his body slacken, like he was giving up. Like Guasco had read his intention and he was now thinking of a new plan.

Guasco relaxed, too. Relaxed instead of seeking to grab the initiative. Fatal mistake.

Nicholas Doria suddenly exploded forward, driving a thrust to Guasco’s face so fast you might have missed it if you blinked at the wrong time. Guasco instinctively tried to push it away with his sword and step backward. He managed to deflect it a bit, but with a small turn of the hand, Doria turned the point so it curved ever so slightly around Guasco’s sword and bit into his face with the deadly point, just barely missing Guasco’s nose.

No one would be calling Guasco pretty after today.

Doria was not done, but kept on Guasco like a rabid dog, jabbing forward with strong thrusts, one after the other. Guasco forgot all his training and fled backwards, trying to get himself away from danger, flailing at Doria’s sword, trying desperately to knock it away, waving around hither and thither with his rotella.

It was inevitable that Doria would find another opening against the quivering mess, slipping his sword past Guasco’s guard and jabbing him in the face on the other side of his nose. Then, as if sensing danger, Doria jumped away and set himself back into guard.

Then the two fighters regard one another, both panting from exertion and fear. Doria smiled at the sight of blood trickling down the sides of Guasco’s face.

In the arena it was so quiet, people would later say you could hear a feather hit the ground. Perhaps Guasco had had enough. Perhaps he would surrender.

Guasco banged his sword and shield together angrily to show that he was not done fighting.

Doria began making his deceptive motions again, but credit had to be given the younger fighter—Guasco had learned his lesson. He refused to remain passive but hurled a thrust of his own at Doria, a thrust that took Doria by surprise. He could only parry it off the front of his rotella without making an attack of his own. Encouraged, Guasco came forward swinging mighty blows, and now it was Doria’s time to give ground. Doria stepped back and a little to the side. The sight of Doria on the retreat roused Guasco to swing with greater power.

Naturally, Doria was not really being overwhelmed but was letting opponent walk himself into a trap. By retreating at a slight angle that put Guasco on Doria’s right side, he had been luring Guasco to death. In his fury Guasco failed to recognize this and moved into the trap, proceeding straight forward against an opponent retreating at an angle.

Guasco was nearly about to strike Doria when the crafty older fighter sprung his ambush. Doria just barely avoided a mighty downwards blow from Guasco, and then stepped forward and drove a thrust to Guasco’s belly again, a thrust that went over Guasco’s sword to keep it from striking back.

Panicked, Guasco raised up his sword but this only had the effect of bringing Doria’s sword towards Guasco’s face. The point bit into the corner of Guasco’s eye, making Guasco scream in pain and terror. With a touch of theater Doria twisted the sword violently to make the point bite even more violently into Guasco’s eye as he desperately pulled himself away.

Now more beast than man, Guasco came forward almost maniacally, pulling his shield in front of his face and throwing blows with a force born from a man who feels himself hanging over the burning coals of Hell.

Doria was shocked at the strength of Guasco’s response — what did he have to do to finish off this kid? He had naturally concluded that pretty boy Guasco would fold up at the first major hit, but Guasco had a surprising resilience and a ferocious determination.

Guasco’s blows now came with force enough to hack parts clean off a body. Doria moved around them adroitly but also with fear of the flashing iron. He sought a chance to strike at Doria’s unprotected legs, either to hamstring him or open up the artery on his thighs or perhaps to take out a knee. That would put a stop to this fearless young man.

Doria sought the safe opening but the wild and violent movements of Guasco were too unpredictable—nothing so undoes a carefully prepared plan as the pure chaos of rage. Doria finally saw his attack, and came forward, then Guasco’s sword flicked quickly upward with its back edge and threatened Doria’s unprotected left hand. Doria flinched backward.

Guasco now aimed a mighty downwards blow to the small gap between breastplate and helmet. Doria raised his shield to block the coming right blow, felt Guasco’s sword make hard contact with the rim of the rotella. Then a large chunk of Guasco’s sword came off and went flying at Doria. The edge of this sword chunk struck into Doria’s breast plate with a high-pitched ping. Feeling his advantage Doria brought up his sword for what he was sure would be the deadly stroke against, since without a sword Guasco could not defend both his head and leg.

But his plan was interrupted by the loud call of a trumpet. Guasco backed off and Doria froze in confusion.

The Duke was shouting, “Stop!”

Frustrated that he finally has the chance to kill Guasco and it is being taken from him, Doria threw his sword to the ground in disgust.

Both fighters, exhausted, returned to their sides of the arena.

The Duke went to Guasco to verify the wound to the eye had not robbed him of sight. Once the Duke was satisfied he called for a new sword for Guasco.

Filippo Pepoli, Doria’s padrino, heads into the arena and retrieved Doria’s sword. After a quick inspection, he gives Doria a curt nod of approval and hands him the weapon.

As the two warriors were no longer fighting, a few men dared to shout encouragements to Guasco. One Frenchman who cried, “Finish him Doria!” was met by disapproving hisses and icy glares.

The Second Assault

At the cry of “On Gentlemen!” the two sword fighters emerged from their sides of the arena.

Many doubted that Guasco still had the strength or energy to fight after the nasty wounds that he had received. As if to prove his doubters wrong, as if to prove his opponent still had much to fear, he came out of his corner using the same elaborate footwork combined with loud swashes of his sword into his shield. By contrast Doria came from his side with lackluster energy. He simply walked to the middle of the field in a relaxed manner and not forming himself into guard until he and Guasco were within distance to fight.

To those close enough to see the fight well, they would remember that Doria’s complexion had taken on an even sallower hue at this point in the fight, about a half hour after it started. Doria had recently suffered a bout of malarial fever – an endemic problem for Italian summers – and some hypothesized that he had not fully recovered his strength. Others said that it was just a natural function of his temperament. Choleric men like Doria were known to be quick to anger, but also quick to tire, a fact noted in the works of the famous warrior, Pietro Monte.

Whichever was the truth, everyone agreed that Guasco demonstrated more spirit, a surprise considering the wounds he had suffered.

But Doria once again proved his superior tactical acumen. He placed himself into a right foot forward guard. At first this appeared to be so he could more easily make quick thrusts. But Guasco was quickly able to cover this with tight scooping parries with the back edge of his sword.

With his right foot forward Doria was able to conveniently circle towards Guasco’s right side while remaining in a perfectly fixed guard. This was a particularly clever tactic for the situation, because blood was still getting into Guasco’s right eye and interfering with his vision. Of course, Guasco responded by turning in place so that the two men appeared to be circling one another. In the first assault between the two men Doria had stolen time from Guasco by prodding at him with his sword, now the skilled Doria was stealing space from Guasco.

In a deadly fight like this an inch was as precious as a pearl, an inch was often difference between survival and death. And as Doria was in constant motion and Guasco’s eyes were unable to detect the small changes in distance, Doria was stealthily closing the space.

In the audience the experienced fighters could see it. Though the two men were circling one another, from above it was more like Doria was stepping a gentle spiral that would end at Doria. To disguise his plan, Doria occasionally made quick feints to Guasco’s shield side to keep him occupied and not being aware of the growing danger.

Before long Doria would be so close that that he could jump forward and thrust at Guasco over Guasco’s sword. At that point the fight would end. Guasco’s many friends wanted to shout a warning to him, but to break the rule of silence was death. They could do naught but pray as Doria moved to the point where he could strike and Guasco would be lost.

The great master Achille Marozzo emphasized the importance of not lingering in any one guard, since skilled fencers knew the weakness of every guard. Marozzo’s student Emilio Marescotti, Guasco’s padrino, had imparted this wisdom onto Guasco in preparing him for the fight. Guasco suddenly remembered this precept and made a change of guard without stepping, so that his sword moved to a position in front of his left knee and so that his back edge faced the approaching Doria. This also changed the position of his head so that he could suddenly see Doria with his good eye.

This was the guard of the boar, an ideal guard for receiving an attack. Doria knew it was dangerous to attack the boar, but after working so long to get into position for a strike he could not stop himself from launching forward.

The thrust came straight at Guasco’s face, until Guasco caught it with the back edge of his sword. The back edge gently nudged aside Doria’s thrust and the point of Guasco’s sword was now going toward Doria’s face. Guasco stepped forward in making this defense so that the rims of each other’s rotellas were mere inches apart and Doria was fully occupied in defending his face from being hit.

Doria pushed Guasco’s sword aside. Guasco, with a practiced motion brought his sword down low to make a cut at Doria’s leg. Rather than back up, Doria, savage as a pack of half-starved hyenas, stepped forward and drove the rim of his rotella at Guasco’s helmet, determined to knock him out, but Guasco was moving at the same time. Doria’s blow to the head with the rim of the rotella hit Guasco but the curvature of the helmet mostly deflected the energy of the blow.

Guasco’s blow to Doria’s leg hit right into the man’s unarmored thigh. But the blow to the head had knocked Guasco askew, so that his stroke came out of alignment and rather than cutting into Doria’s leg, he simply slapped it with the flat. Guasco then tried to turn his false edge up in a blow to Doria’s sword hand, but Doria was now backing away from the larger man.

For a moment the two men stared at one another, panting for breath, both men braising in their own sweat. Guasco hoped that Doria had enough of this, that honor would be satisfied. But the sight of blood on Guasco’s face, some of it weeping from his eye kept him in fighting spirit. Doria fixed Guasco with a gaze of such hatred that the younger man knew his opponent would never stop.

Doria raised his sword up into the Unicorn with the hand high and the point dropping down towards Guasco’s eyes. Guasco himself, having been saved by remembering his padrino’s counsel, now refused to remain in a guard, but moved between all those that he knew, from the Guard of the Face with the sword extended in front of him and the rotella over his hand, to the Long Tail Guard with the point extended behind him like he was some kind of beast with an appendage of iron.

Doria tried to use the sun to his advantage from the Unicorn, hoping that he could get Guasco to look up at the sun. But since Guasco was constantly changing from guard to guard, his head never looked in the same direction for more than a second. This frustrated the already troubled Doria, having trouble developing a plan against an opponent who flitted from one guard to another like a butterfly. Worse for Doria, he felt fatigue setting into his marrow like a sickness. Those motions that had been crisp were now losing their sharpness.

And that is when he thought of the attack he would make. Once again he would attack Guasco’s weakened vision. He knew it could not fail. The Florentines called it the High Assault, but he liked to think of it as the Magician’s Guard, because it was like magic.

Skilled warrior that he is, Doria knew that all attacks must be watched over by a bodyguard of deception. So he started by working Guasco forwards and backwards, stepping forward with a thrust and then stepping back before Gusaco can reply. In doing so he was training Gausco to look straight ahead and move in a straight line in imitation of Doria.

Guasco obediently followed this part of the plan, stepping straight forward when Doria retreats, stepping back slightly when Doria advances. Since Doria’s steps forward were short and the steps back were wide, Guasco was gaining a portion of the field and the honor that came from it.

As he proceeded through his plan, sweat trickled down into Doria’s eye. How much the worse this must be for Guasco he thought. So much the better.

Once Guasco was suitably conditioned, Doria made his attack. He threw another thrust and then raised his sword into the Unicorn and drew his body back into itself. Guasco came a little forward into the little vacuum created by Doria as he has become conditioned to doing. As Guasco stepped forward, Doria unleashes a descending thrust to Guasco’s face with an overpowering force. Guasco starts to pull back and turn his body to cover this thrust with his shield. Then Doria pulls his hand back and starts to pull a strong reverse cut towards Guasco’s head.

Guasco stayed in good order, the fatigue not affecting him and brought his back edge up to ward off Doria’s cut. But the swords would not meet and Guasco would not feel the reassurance of the blades clashing.

Instead Doria has pulled his cut back into a position so that his sword is level with Guasco’s eyes and with Doria’s elbow above his ear. At this angle the blade of the sword had almost completely disappeared. Only the pinprick of the point was visible, but through the blood and sweat Guasco could hardly see it.

There was a perfect target for Doria in a little space between rim of Guasco’s shield and the cross of his sword. He thrust straightforward.

At the same time Guasco was turning his head to try to get a better look at Doria’s sword, since the little pinprick of the point looks the same whether the thrust is coming forward or remaining stationary. He saw to his great fear that there was a thrust coming right at his good eye. Guasco violently threw up his shield and lifted his sword and turns his head away. These are for naught and the point lanced into his face. Fortune was with him though for the point was not fatal nor did it hit his other eye.

Guasco was now hopelessly unbalanced and vulnerable. He fled backwards, but a man can step further forward than he can backward. Doria threw a strong cut to Guasco’s face again, which Guasco blindly blocked, since he was sweeping around with his back edge wily nily.

Fully frustrated and feeling his opponent’s life in his hands, Doria coiled up to drive a killing thrust, the beast within taking over, instinct aiming that thrust into Guasco’s torso. He uncoiled, releasing the tension in his body, stepping forward and delivering that thrust with all possible force, hoping it would find a gap in Guasco’s armor like Doria’s last thrust. Such a point would go through his organs and up into his heart.

But fortune smiled on Guasco once again. Rather than a chink in the armor, Doria now drove his thrust into a flattish section on Guasco’s breast plate that would not yield, would not allow the least penetration.

Doria cursed and drew his sword back for another thrust to Guasco’s face, but as he brought the sword towards Guasco he noticed that the point was off to the left, nearly perpendicular to the direction his hand was going. Then he realized what had happened: he had thrust into Guasco’s breastplate so hard he had severely bent his sword!

Since Guasco’s sword had broken and been replaced, Doria backed away from the fight and held his sword up for the Duke to see that it was broken.

A resounding blast of the trumpets brought the duel to a halt once again.

The Duke was ready to supply Doria with a new sword but Guasco’s padrino Emilio Marescotti objected. “Doria’s sword is not broken.”

Doria’s Godfather Filippo Pepoli said, “Are you blind Marescotti? It’s more bent than your father was, until he was put down like the dog he is.”

The Duke was irritated by this invective and said, “Silence, Gentleman. We have a lawyer on hand to solve this issue.”

If there is one thing that was to the Italian duel it was the existence of the duel lawyer. You might be forgiven if you were to assume that the primary purpose of the duel lawyer was to find a way for a man to finagle himself out of a duel while keeping his honor. But at the duel itself it was useful to keep a lawyer on hand and one now came forward to resolve the issue according to the Code of the Duel.

After hearing the two parties the duel lawyer advised the Duke to return Doria’s misshapen blade to him, since it was bent but not broken.

And so it was that Nicolas Doria had to fight with a bent sword, and that Christopher Guasco had managed to put himself in a position to win the duel after having cheated death twice.

The Third Assault:

With his bent sword in hand, Nicholas Doria emerged from his corner without much vigor or enthusiasm. Neither did Christopher Guasco demonstrate much spirit—while he understood his advantage, he had stood in the shadow of death and it left his spirit cold.

The two fighters came together in the middle of the arena. It seemed clear that it was Guasco’s turn to initiate the offensive. Guasco now placed himself with the right forward and remained fixed in an offensive guard and now it was Doria’s turn to transition from guard to guard to make things as difficult as possible. Guasco tried to attack Doria from a distance, entering with a thrust and then cutting to the leg, but Doria used his rotella to cover the thrusts and backed away from the leg cuts. At such a wide distance Doria had plenty of time to withdraw.

Guasco drew closer and made his attacks from nearer to Doria, but again Doria managed to get his leg just out of the way of each of Guasco’s attacks. Finally, Guasco realized he was not getting anywhere – Doria seemed to know the goal of his attack as soon as Guasco thought of it. So then Guasco drew close, so as to make Doria think he was going to attack with a thrust and cut to the legs again.

Unfortunately for Guasco he was like a neophyte trying to bluff a Poker master. Doria gathered his muscles in tight for what he knew was coming.

Guasco launched forward and stabbed at Doria’s face once again, Doria quickly stepped to the side. Then instead of striking to the leg, Guasco drew his thrust back and tried to stab Doria again, as Doria had just done to him. But unlike Doria, Guasco did not level his point before Doria’s eyes to make the sword disappear, and it would not have mattered if he had done so.

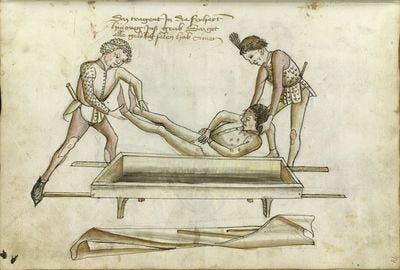

Doria was already turning his body and now parried this second thrust with the rim of his rotella and he did this as he dropped his sword and jumped forward.

The two men crashed together and a bitter fight ensued for control of the one good sword. Doria grabbed Guasco’s sword by the guard and yanked on it, but the bigger man turned his body, trying to take Doria away from the sword. In the process he banged his rotella into the side of Doria’s helmet, but without enough force to stun him through the protection of the helmet.

Doria was meanwhile focused on taking control of the sword. He brought his rotella arm forward and used his hand to take a weak hold of the elbow, while moving towards Guasco’s blind side and grabbing his wrist.

Sensing himself in danger, Guasco quickly switched the sword out of his right hand and gripped it awkwardly about the blade with his left hand.

Growling in frustration, Doria threaded his arm underneath that of Guasco and clamped his right hand onto the wrist.

Guasco pivoted so violently that the sword tumbled out of his hand and fell to the ground, and in that same motion Doria went flying on top of it. As Doria had a tight hold upon Guasco, the younger man tumbled onto the ground.

Now neither man could think of reaching for the sword, as they were engaged in a savage battle of limbs, hand to hand, tooth to tooth.

At one point Guasco grabbed Doria by the beard and pulled his head to the side and then used the moment to mount on top of him. The fight now turned savage to a degree none expected. Guasco lowered his head towards Doria and began tearing at the man’s face with his teeth. Doria screamed and thrashed around, but Guasco had him firmly in control.

Doria pulled his face away from the teeth and Guasco savagely bit Doria on the nose and shook his head back and forth like a forest creature until he tore a chunk of his nose off.

As Guasco did this he fiddled with Doria’s helmet and then finally ripped it askew. Doria tried to move his head and to keep, but Guasco just drove a head butt into his face. Doria struggled without success to escape. Guasco clamped his jaw down upon the man’s ear and started trying to tear it away from his head. Blood spurted from the wound and covered the area around Guasco’s mouth.

In the process he was also able to tear Doria’s helmet away from his head.

Now Guasco took that helmet and started bashing Doria on the head with it, until Doria moved. Sluggish and slow from these wounds he was not able to keep Guasco from grabbing the weapon that was beneath him.

Guasco jumped away and Doria leapt after him. But as he did Guasco leveled a mighty stroke to the crown of Doria’s head that dropped him to the ground and left him incapable of movement.

Guasco held the point of his sword at Doria’s bare neck.

“I surrender,” cried Doria.

The trumpet cried and the arena crowd shouted in triumph. The victor stripped the helmet from his head, and this caused a collective gasp.

Christopher Guasco had gone into the fight in the full beauty of youth, but emerged an ugly, scarred man with a blood-covered face who stirred pity rather than fire into the hearts of young maids.

Still his portion was a victory, a far better fare than the defeat that was now Doria’s ration to eat, today, tomorrow and every day until the good Lord took him from his misery or the the Devil called him home.

The Aftermath:

Nicholas died a few days later of his wounds and his shame in Ferrara.

Christopher Guasco enjoyed a short career as a successful officer of the King of France, commanding as many as 2,000 infantry at one time in the French King’s wars against Charles V. Eight years later, he would team up with Guido Rangoni—the Patron of Achille Marozzo—and defend a fortress near Turin in Northern Italy. When this fortress fell to the armies of Emperor Charles V, Christopher Guasco tried to retreat, but fell into a river and drowned.

As to Ferrara, among the people that watched the fight was Ercole d’Este, the future Duke of Ferrara and and he was so disgusted by this fight and others that he shut down the dueling arena in 1540, turning it into a park for the people of Ferrara. It would later be used for another kind of duel that swept Europe, the battle between two men armed with rackets: tennis.

The Sources:

Letter I: Letter of Bernadino Fiamingo August 26th 1529 to his patron Signore Polo

Letter II Niccolo Michiel Proveditore, same date to various persons

Letter III: Letter by Piero Franceschi to Andrea Francesci August 23rd

And epic Latin poem of the duel by Gabriel Ariosto from Francesco Borsetti's Historia almi Ferrariae Gymwasii.

Achille Marozzo’s description of the Sword and Rotella

Antonio Manciolino description of the Sword and Rotella

Francesco Altoni description of the Sword and Rotella

The Sixteenth Century Duel by Frederick Bryson

This is admittedly uncertain. Bianchini describes Hugo Pepoli as a cousin to Guido Rangoni and the closest possible connection of consanguinity between their clans in the early 1500s derives from the marriage of Isotta Bernadino Rangoni to Guido Pepoli. Isotta shared a great-grandfather with Guido Rangoni, thus making them second cousins. Isotta was then a sister of Guido Rangoni’s political rival Gherardo Rangoni (d. after 1522) and the possible cause of the famous duel between Hugo Pepoli and Guido Rangoni in 1516. To this date no record of Hugo Pepoli’s parents or siblings has been found. However Hugo was taken as a hostage by the Pope due to Alessandro Pepoli’s actions on behalf of the Bentivoglio in 1508 and Alessandro was a son of Isotta Pepoli and Guido Pepoli and so likely also Hugo Pepoli’s brother, since Hugo would have little value as a distant relation.