As we get into this, I want you the reader to understand the importance of having primary source material readily available. Jean Chandler has devised a tremendous project called, No Source Left Behind. The goal of this operation is to make primary historical source material related to western martial arts readily accessible, searchable and available to all. While this project is still in its infancy, I can’t express enough the importance of such an endeavor. When this project gets off the ground, please consider giving Jean all of the support he needs, and consider contributing to the library yourselves.

When I get a new primary source in my hands, the first thing I do is check the appendices for any clues related to Fillipo Dardi, Guido Antonio di Luca, Achille Marozzo, Antonio Manciolino and Angelo Viggiani. I always strike out. After years of searching I finally got my hands on one of the best 16th century Bolognese sources, Fileno dalla Tuata. Interestingly, this time around, I didn't do my cursory dig, I put the books on my shelf, and just let them stare at me, and boy did they stare—all-three-volumes.

Finally I took some glances, checked the important dates in books I and II, took a few notes, and walked away.

To be fair, I'm in the middle of a massive project which will be published soon, so my mind has been spinning with 1444-1445 Bologna and all the murder, intrigue, and factional violence therein.

This week, I had some unexpected time off of work, so I finished first drafts of two of the articles I've been working on, started a third one, and needed to take a break. Call me a nerd, but my idea of a break is going down rabbit holes I’ve been putting off but I’ve always wanted to chase, and my pet project for a future date is the two sword duels of Ascanio Della Corgna.

My dig for Ol' one-eye started with scouring Vizzani for any mention of his duel in Bologna, and when that struck out I decided to crack open della Tuata. Why not?

Sometimes the best things happen out of sheer dumb luck—sometimes your ignorance leads you to the best discoveries, and when you have a hot hand, you've just gotta play it. Right?

I cracked open dalla Tuata book III, and did my cursory look. It's too early for an Angelo Viggiani sighting, he was born in 1517 and Della Tuata only records up to 1521, but I could see his ancestors. Noted. Plenty of Manciolinos but no Antonio or Francesco; that would be Tony and his old man. Bummer. On to Marozzo—

2 Entries!

Entry #1:

1460

A di 13 de novenbre Zeronimo de ser Ghuiduço da Montiveglio citado be Bologna habitadore in Saragoça adandosene a chaxa fu moto da un'ora de note dal seraglio de Saragoça <da> dui vilani çoè da Domenego de Lanço da Chrespelano e da Inglero da Mongardino.

A di 14 pu preso Angliero e di 15 tanagliato vivo per la tera e poi squartati e messo li quatri ale porta, avea anni 24 e fu preso in Galeria in casa de Alberto Morozzo perche erano andate strete cehride chi l’avesse o tenesse e avra cento duchati ala choa.

On November 13, Geronimo (son) of Guiduco Montiveglio, a Bolognese citizen living in Saragossa, was attacked and killed by two peasants as he was coming home. These were Domino di Lanzzo from Crisilpino and Angliero from Mongardino

On the 14th Angliero was captured in the Galiera and on the 15th he was tortured alive in public and here quartered, and those quarters placed upon the city gates. Angliero was twenty-four years old at the time. He had been taken at the house of Alberto Marozzo, in respect of the reward of one hundred ducats promised for Angliero’s capture, an offer made by strict proclamations.

Entry #2:

In 1512, Annibale II Bentivoglio recaptured the city of Bologna with the aid of the French. In response the armies of the Holy League (Papal States, Swiss, and Spanish) gathered to besiege the city.

Fileno Della Tuata, who was a resident of the city at the time, kept records of everything. In the muster roll of Annibale II’s army, recorded in Della Tuata there appears one Marozzo and Maestro Guido Antonio. Here's what it says {Note: I’m only listing relevant names of the 135 listed, and names associated with titles that give context}:

1512

A di 22 de setenbre vene doxento fanti romagnoli che andavano a Bresa mandati dal papa.

A di dito vene in Bologna mile sviçari solda’ del papa che andavano in Romagna al ducha d’Orbino.

A di dito veneno per la via de val de Reno tremilia spagnoli infra a piè e chavalo per andare a Bresa, e anno tanta roba robata a Prato e in altri luoghi ch’è una maraveglia, e qui ne vendeno asai, e fu una chosa da non chredere che Spagnoli Sviçari e Romagnoli giunseno a un’ora medexema al ponte da Reno, e tuti se salutorno amichevolemente.

A di 25 funo chiamati ala renghiera del podestà per ribelli de Sante Madre Ghiexia li infraschriti, in tuto 310:

ser Antonio di Ferari da Chrevalcore

ser Achile de ser Jachomo Malchiavelo

ser Antonio Paganelo

ser Domengo Fabruço

Bazon peschadore

Baldasera Ganbarelo sarto

Conte dele Agochie becaro

Michele da Pisoja fornaro

ser Martin da Sasun

can<celliere> de m. Haniballe

Sforcin dito Gato stafiero de m. He<emese>

Sixmondo de mastro Ghuido Antonio.

Straçaveludo stafiero de m. Han<ibale>

Tomaxe calcolaro dito Maroço

Orabon dale Agochie

ser Petronio da Schanelo

Zoane calçolaro dito Castelaço

1512

On September 22nd, 1512 two hundred Romagnol infantry were sent to Brescia by the Pope.

On that same day a thousand Spanish soldiers in the service of the Pope came to Bologna, en route to the Duke of Urbino in Romagna. They have stolen so much stuff in Prato and other places that it boggles the mind.

Also on that day a force of three thousand Spanish soldiers, including infantry and cavalry, came to the road through the Valley of the Reno. They were going to Brescia. They are selling a lot of their loot here. Perhaps the strangest part is this: all three bodies of men met at the bridge over the Reno, and all greeted one another amicably.

On the 25th the below mentioned individuals (310 in all) were called to the rostrum of the Podesta for rebelling against our Holy Mother Church.

Sir Antonio di Ferari of Chrevalcore

Sir Achille of Sir Giacomo Malchiavelo

Sir Antonio Paganelo

Sir Domengo Fabruzzo

Bazon, fisherman

Conte dall’Agocchie, butcher

Baldasera Ganbarelo, tailor

Michele da Pistoia, baker

Sir Martin of Sasun

Chancellor of Annibale {Bentivoglio}

Sforzin aka the Tom Cat, groom of Ermese {Bentivoglio}

Sigismondo of Master Guido Antonio

Strazaveludo groom of Annibale {Bentivoglio}

Tomasso, Clerk of said Marozzo

Orban dall’Agocchie

Sir Petronio of Schanelo

Giovanni shoemaker called Castelazzo

First entry: Alberto Marozzo the bounty hunter in 1460—what a fascinating insight. Not only does it illustrate a legacy of Marozzo's in Bologna; which helps lend credence to Oriolo’s claim that the Marozzo family (from the Ludovico branch) were granted citizenship in 13851, thanks to two cousins already living in the city {still need to track this down}, it also gives a location of residence in Galleria, which was on the northside of town. It could also show some level of martial competency, because capturing a fugitive murderer in a city full of hidden daggers probably wasn't an endeavor to be taken lightly.

Now lets discuss that second entry.

Marozzo’s—Maestro’s—and dall’Agocchie’s—Oh my!

There is so much to explore here. Let’s start with Maestro Guido Antonio. Sure, this could be Master Guido Antonio {Insert name here}, but Alessandro Achillini {a known Bentivogleschi} was a big fan of Okham so lets pull out our razors. The explanation that requires the fewest assumptions is usually correct.

We know that Guido Antonio di Luca trained Annibale II’s nephew, Guido Rangoni, the son of the Bolognese Captain of Men-at-Arms, Niccoló Rangoni.2 We know that Guido Antonio di Luca was in Bologna from 1496 until his death in 15143; so he’s still alive. It is proposed that Guido Antonio di Luca was in the service of the Bentivoglio4; furthermore Marozzo and della Tuata both call their Guido Antonio’s a master.5 Am I missing anything?

Let’s start chipping away some of the logical delineations. If this was a master butcher, or master baker, della Tuata would’ve likely just called him becaro or fornaro, at this point I think I’ve looked at every name in this book, and I have yet to see a master baker, but I’ve seen a lot of bakers—maybe I missed something. It's noteworthy that the title Massaro was used for guild officials elected into the Anziani, but the title has been used in the context of the lists present in dalla Tuata, in regards to military affairs.

Why only provide his given name? Great question! This will help us build into my next point, so let's take a bit of a dive. The list that Felino della Tuata copied is a full of colloquialism and shorthand. Something to consider is that most of the Bentivoglio captains and men of authority in Annibale’s rebel army are not explicitly listed. When Annibale, his brothers, and his loyal supporters were sitting in Parma recruiting an army to recapture Bologna, or as in this case when they were in Bologna recruiting Bolognese citizens to hold off the Holy League, they weren’t exactly scrupulous about the details, and did not record known entities.

In our list of new recruits, we have a variety of different notarial elements, if it's a name of repute, we get the full name, if it's not, we often only get their given name. For most of the positions like groom or chancellor we only get the first name, and sometimes no name at all.

Thereby, this could be Sigismondo the son of Maestro Guido Antonio or this could be Sigismondo of/serving Guido Antonio, heck it could be one of Maestro Guido Antonio’s assistant instructors. Either way it's fascinating. A reference of Maestro Guido Antonio in the wild.

That brings me to the next important name on this list, Tommaso calcolaro dito Marozzo. This one is fascinating, and provides an interesting puzzle due to the later context; that is Zoane calçolaro dito Castelaço. This could be Tomasso clerk of said Marozzo, it could be Tomasso clerk called Marozzo. More likely it's a typographical error {c instead of ç; which is a z or zz} and this is Tomasso shoemaker known as Marozzo.

Just to indulge—we know from Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Niccolò Machiavelli, and the many circulating copies of Vegitus that infantry blocks were calculated with square roots. It's possible that calcularo was a position assigned to infantry commanders, someone who would title themselves Maestro Generale d’ l’Arte dell Armi perhaps, and said role would surely have need of an aid to help them calculate unit dimensions. It's more likely that this position was a clerk or paper pusher, Florio defines this simply as someone who computes, calculates, or reckons.6 It's worth noting that the title does show up repeatedly in the text with the c variation, and it's always in a military context.

Of course, if I take off my rose colored glasses, that's not the case, but a guy can dream can't he? Regardless, Tomasso Marozzo the shoemaker, could provide some intriguing context as to why Marozzo purchased a mill in 1531. Family business? We’ll get into that some more in a moment.

As enjoyable as those hypothetical forays into Marozzo and Maestro Guido Antonio were, we have one last point to address before we get into some more intriguing discoveries.

Conte dele Agochie becaro and Orban dale Agochie. Stephen and I have been aware that the dall’Agocchie family were loyal Bentivogleschi for some time. However, this is the first time that I've seen them listed as butchers, which makes a world of sense.

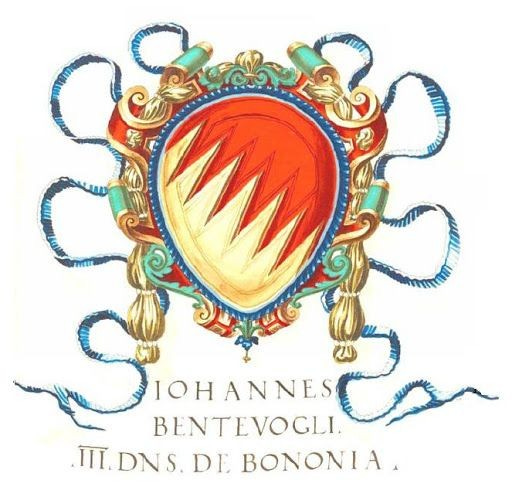

The butchers in Bologna were for all intents and purposes a paramilitary force for the Bentivoglio, and ties between the family and the guild go all the way back to the Bentivoglio’s origins as butchers.7 Hints the Sega, or saw, in the Bentivoglio coat of arms. I was going to keep this one close to my chest until part 3 of the Manciolino saga, but I have similar evidence that the Manciolino family were also butchers before they joined the notarial class and tried their hand at politics.8 Given the fact that the Butchers were one of two craft guilds to have an arms society or militant wing of the organization, we might have some compelling context to explore here.

There's no doubt that Achille Marozzo trained with Guido Antonio di Luca. What we haven't been able to connect is how someone like Antonio Manciolino, or say a later Giovanni dall’Agocchie came to train in, or became acquainted with, the presumed system. The Bentivoglio are certainly the nexus—the challenge has been connecting those figures to that nexus. Now we might have clear connections for Viggiani, dall’Agocchie, Marozzo, and Manciolino.

Ghirardacci records that Orabone dalle Agocchie (our Orban above) and Don Piero dalle Agocchie left Bologna with the 500 loyal Bentivogleschi in 1506.9 For the sake of completeness, we can add Alessandro Achillini to that list as well.10 Prior to that in 1497, Giovanni II Bentivoglio invited his dear friend Battista dall’Agocchie to his Palazzo for dinner to listen to the new bell he had commissioned in hopes they could enjoy its splendor together.

The relationship is obvious, but the reason for the relationship might be made more clear now that we know that the dall’Agocchie family had ties to the butchers of Bologna. That leads me to another thing I came across when I was poking through some books on heraldry in the Estense library.

In Angelo Maria da Bologna’s, Araldo nel quale si vedono delineate e colorite le armi de' potentati e sovrani d'Europa, we get the following:

Empowered with the knowledge that a likely ancestor of Giovanni dall’Agocchie was a butcher, the bull and sega motif here makes a world of sense. The arms of the Butchers guild in Bologna was a bull, and just as we saw with the Bentivoglio sega, the saw was another common motif used to represent descendants of butchers.

The dall’Agocchie weren’t the only obscure Bolognese family represented in this book. The Viggiani family made an appearance as well. We have seen Melchiorre Viggiani; a Bolognese knight and diplomat, and Nanni Viggiani here, and soon you’ll get a chance to meet Spezza Viggiani in our series on the Canetoli vs Marescotti blood feud. Though long venerated Bentivogleschi, Nanni Viggiani severed the ties between the two families in 1449, when he followed the Pepoli and Fantuzzi families in an attempt to overthrow Sante Bentivoglio.

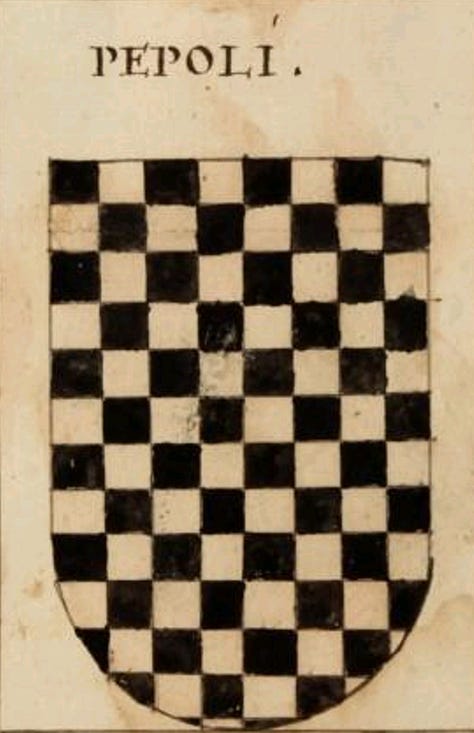

And of course also present were the stalwarts of Bolognese history; the Marescotti, Fantuzzi, Malvezzi, Caccianemici, Rangoni, Bentivoglio, Pepoli, Gozzadini and Zambeccari. Names you are no doubt familiar with by now, and if you’re not, feel free to check out some of the articles on Bolognese history in our back catalogue. These are names you’ll come across quite frequently!

From Marozzo to His Students

Lets just say I was a little jazzed up to find so many Bolognese Fencing adjacent characters in such a short period of time, especially in one spot {dalla Tuata}. So, I decided to take a shot in the dark—if a Marozzo was in Annibale II Bentivoglio’s retinue, would he/they show up in the Modenese chronicles after the Bentivoglio were expelled from Bologna in 1506? They staged their first campaign to retake Bologna in Modena in 1507, so it wouldn’t really be that much of a shot in the dark.

The answer is no.

At least not that I've found—yet. But I did come across this, which first appeared in English in Swanger's publication of Marozzo's Opera Nova (pg.20):

Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti:

Lunedi a dì 22 mazo. Magistro Achillo Morozzo bolognese al presente maestro de giochare de scrima in Modena, ha fatto stampare uno libro in quarto de carte 156 intitulato al Illmo Sig. conto Guido Rangon zentil homo modeneso, el quale libro tratta de tute l'arme et abatimenti da pede e da cavallo, et de molte prexe da pugnale, como per le figure in ditto libro appare con le guarde da tute le arme et li lhori modi, et che tratta de casi ocurenti al combattere in stechade, el qualo lo ha fatto stampare in Modena in casa de don Antonio Bergollo, e a lui proprio preto modenexo del anno presente 1536 a dì 24 mazo, e lo ditto M." Achillo è de età anni 52 e dice havere principiato ditto libro et opera sino del 1516; e io Thomasino Lanciloto modenexo l'ho veduto questo di 22 ditto mazo finito de stampare; e perchè la opera è degna de memoria, per questo io l'ho notato in questa mia cronicha.

Monday, May 22. Maestro Achille Morozzo of Bologna, the present fencing master of Modena, had a book printed in quarto with 156 pages, dedicated to the illustrious signor Guido Rangoni gentleman of Modena, which book deals with all of the weapons and abattimento on foot and against horseback, and many dagger presses, as for the figures in said book it appears with the guards of all the weapons and their uses, and deals with cases occurring when fighting in the stakes, which he had printed in Modena in the house of Don Antonio Bergollo, and in his own Modenese shop in the present year 1536 on the 24th of May, and the said Maestro Achille was the age of 52 and he says he started the said book and work in 1516; and I, Thomasino Lanciloto, saw it finished printing on the 22nd of May; and because the work is worthy of memory, I noted it, in this my chronicle.

The important details here are that Marozzo’s Opera Nova was finished printing on the 22nd of May, and officially published on May 24th 1536. Better yet, we know that Marozzo started writing in 1516, and it took him 20 years to complete.

I began this little work of mine (which in truth is nothing fancy, but is useful, if I'm not mistaken) a long time ago.

—Achille Marozzo (Swanger)

However, I think the most important thing here, something I had honestly forgotten, is that at the time of publication Achille Marozzo was the present fencing master of Modena. Why? Because this reminded me to take a peak in Lancellotti for Marozzo's named students!

So, reader who reads this, do not resent it, because I am certain that slanderers and detractors of others efforts and virtues will try to denigrate and completely erase its good reputation; nor will these friends seek to place it in its deserved place, like the strenuous captain Emilio Marescotti, captain Giovanni Maria Gabiato, and captain Battista Pellacani, along with the many other worthy knights-at-arms who through my industry and concern can be seen at the height of this noble art and glorious virtue…

—Achille Marozzo (Swanger)

Sure enough, a few pages later we get:

El Sig. Governatore ha fatto intendere a M. Imilio Marescoto et a M. Zan Maria de Gabia agenti del Sig. Conte Guido Rangon, che se debiano partire da Modena, e questo per suspeto per essere el conte Guido ala Mirandola.

His Lordship the Governor has made it clear to Messer Imilio Marescoto and Messer Zan Maria de Gabia, agents of the Lord Count Guido Rangon, that they must leave Modena, and this on suspicion of Count Guido being in Mirandola.

This was the first I'd seen of Giovanni Maria Gabiato, which meant that there was a thread to pull—so pull I did. Giovanni Maria was a trusted bannerman of Count Guido Rangoni, he shows up throughout the Modenese chronicles. His first appearance is in 1532, then again in 1536 with Emilio Marescotti, in January of 1539 he was given charge of Spilamberto while Guido went to Venice; where he would eventually die, and his last appearance is in 1540, when he oversees some kids fighting with gesso armor, swords and partisans for the enjoyment of a crowd of Modenese citizens. Now that this is outlined, it bears mentioning that the story of Giovanni Maria Gabiato is better told through the lens of Guido Rangoni, therefore we’ll leave it for another time.

Emilio Marescotti on the other hand is a well documented figure. He’s a bit of a troublemaker, and on account of the fact that his exploits were often more noteworthy—attempted assassinations, duels, feuds, acting as a Padrino in a duel for Chirstoforo Guasco; which we’ll cover in an upcoming article, he’s more dominant in the historical chronicles. We will certainly give Emilio a detailed treatment later on. Emilio got around.

Transalpine Adventure

Speaking of getting around, I’ve been meaning to get around to searching for some biographical details pertaining to Giacomo Crafter d’Agusta, and writing this article inspired me to take another shot before getting back to the grind.

Checkmate!

Jakob Kraffter was born in 1514, to Lorenz Kraffter and Honesta Merz. Lorenz, the son of James Lindsay of Cafford (Crawford) immigrated to Augsburg from Scotland in the late 15th century, and acquired citizenship in 1484. Jakob was born in 1514, and would marry Magdalena Jung on 13 January 1540.11 They had three children; Magdalena (1537), Phillip (1554), and Jacobina (1560).

From the Stadtlexikon Augsburg12:

Around 1484, Lorenz Kraffter († 1521) acquired citizenship in Augsburg. Evidence points to family connections to Nuremberg. He became a member of the furriers' guild. The rapid increase in his assets from 200 (1484) to 6200 guilders (1516) suggests that he was a merchant. His daughter Maria married Jakob Hörbrot . His sons Hieronymus (I, * 1502, † 23.6.1566), Alexander († 1553), Jakob († 1554) and Christoph († 1588) were successful merchants in the middle of the 16th century and were ennobled by the emperor in 1548. Hieronymus maintained business relations with the imperial court, the Duke of Bavaria and the Heidelberg court, traded in spices and textiles at the Frankfurt and Leipzig fairs and had connections to Antwerp, Venice, Bologna, Florence, Lucca and Verona. He supplied the papal mint in Bologna with Tyrolean silver and set up a brass works in Bruneck (South Tyrol) in 1556. In 1559 he came into conflict with the Innsbruck authorities due to illegal silver exports to Italy and the import of inferior money. After his death his company was continued by his sons Hieronymus (II, † 1597) and Anton († 1593) and his sons-in-law under the name 'Hieronymus Kraffter sel. Erben'. The Kraffters were also active in the cattle and especially ox trade . 'Hieronymus Kraffter sel. Erben' supplied the Munich court with oxen from 1570. Hieronymus' (I) brothers Alexander, Jakob and Christoph ran a joint trading company, which was one of the most active companies on the Augsburg money market in the early 1550s. In addition to exchange transactions with Antwerp and Lyon, they were mainly active in the textile trade with Italy. In 1560, the company, which was then under Christoph's management, went bankrupt as a result of financial transactions between him, his brothers-in-law David and Hieronymus Zangmeister and the King of France. In 1580, the Kraffters were among the founders of the Anna College. Jakob's son Lorenz (II) acted as an agent for Augsburg trading companies (including Cristell and Pemer ) in Venice and on the eastern markets; in 1599, 1600 and 1614 he was consul in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice

This is certainly our guy! Yet another avenue for future research. There is so much to explore here, notably the handling of the Papal Mint, the silver trade controversy, the cattle and textile trade in Bologna, and his father's presence in the furriers guild in Augsburg {A hotbed for Liechtenauer practitioners}.

Given Marozzo's ownership of a mill on the Reno, and the Kraffter families trade in textiles, this is another reasonable avenue for future exploration. Essentially Jakob Kraffter was feeding or indulging in all of the major trades of the Bolognese Oligarchy, silver for the bankers, cows for the butchers, and purchasing textiles from the Drapieri.

What about our other two named students?

Battista Pellicani and Giovanni Battista dai Letti continue to evade me. I know that the Pellicani family were noteworthy in Bologna, they show up all over the 15th century, but I haven't been able to zero in on Battista just yet.

While our other Battista, Giovanni Battista dai Letti remains a complete enigma. Unfortunately it's not a name I've seen crop up in the Bolognese chronicles, and my cursory glances at the Modenese chronicles have come up empty as well. I'll keep looking though, maybe during my next writing break I'll find some revealing details about these two gentlemen.

Conclusion

I wasn't kidding when I said hodgepodge. Even though this is a mixed bag of discovery research, there's a common thread through all of this. Marozzo says regarding his detractors, that they won’t seek to put it in its deserved place, like the strenuous captain Emilio Marescotti, captain Giovanni Maria Gabiato, and captain Battista Pellacani, along with the many other worthy knights-at-arms who through my industry and concern can be seen at the height of this noble art and glorious virtue.

Learning more about the lives of Emilio Marescotti, Giovanni Maria Gabiato, and Battista Pellicani could shed some light on the place Marozzo feels his art deserves. What about their lives exemplifies the glorious virtue of the noble art? What can they teach us that Marozzo doesn't already?

What about Jakob Kraffter of Augsburg and Giovanni Battista dai Letti, who Marozzo considers very dear sons and students? Will their endearing qualities help us reason with the lessons of the maestro?

What they do, is help illustrate to the modern reader what competence in the Art of Arms would've looked like. What a martial artist trained in the system should look like. The more we know about Achille Marozzo and Guido Rangoni, the more we learn about the expectations and qualities of Guido Antonio di Luca, likewise, the more we learn about Giovanni Maria Gabiato, Emilio Marescotti, Battista Pellicani, Giovanni Battista dei Letti, and Jakob Kraffter, the more we learn about the expectations and qualities of Achille Marozzo.

Marozzo and Manciolino both define a master as someone who can teach and develop students. Whether they achieved that can be debated; sure, but until we know the intricacies of these men’s lives, we’ll never be able to have a nuanced conversation on the matter.

Proportionally, if that's our given expectation, then we can say for certain that Guido Antonio di Luca was worthy of the title, he was lauded for his excellent students. A Maestro from whose school it can be said that more warriors emerged than came from the Trojan horse—that’s generally assumed to be thirty men.13 Likely thirty Bentivogleschi men. We can learn a lot by exploring their lives as well.

And there’s the catch. The great unifier in this entire story; from Dardi to dall’Agocchie, is the Bentivoglio family. They're the through line of the tradition. The nexus of the art.

Our Marozzo (whoever he was) and son or aid of Maestro Guido Antonio fighting alongside Orabon dall’Agocchie and Conte dall'Agocchie in the Army of Annibale II Bentivoglio provide intriguing context, and tremendous avenues for future research.

The deep connections between the system and the butchers guild, an organization with a long and storied martial legacy continue to grow more substantial. It too presents a through line and construct for how this came to be, and why it persisted for so long. It potentially connects wayward practitioners like Manciolino and provides context for the inclusion of families like the dall’Agocchie in the continuation of the tradition.

By exploring these two intertwining trunks of the schermo we might finally be able to see the whole tree in all of its beauty and splendor. From Dardi and the Marescotti, to di Luca and the Bentivoglio, Annibale II building il Casino for he and his compatriots to exercise and train with weapons.14 Through the twists and turns of the collapse of the Bentivoglio Signoria with loyal adherents fighting to retain the faction’s claim over the city, out into the braches of familiarity with our wayward maestro and his classmate in Modena, and the many sons of the old order holding onto the traditions of their forbearers, and new ones building their own legacy as paragons of the art.

One could even argue that the adaptability, and survivability of the principles, tactics, and delineations makes this artform exceptional. The story of a character like Angelo Viggiani, and his ancestors tells a fascinating tale, surely they continued to preserve their knowledge of the tradition after their exile, but the critical inspiration of separation, influenced the author to become a reformer. While the closeness to the heart of the system likely drove the loyal preservation of the art from a later commentator like Giovanni dall’Agocchie, who admits the need to adapt and reform some principles of the system, yet keeps the core tenants in a familiar language.

Every data point that we add to this narrative, every thread we pull to the warp that brings about the image of this history is essential and beautiful. It's easy for critics to point to the fallibility of 19th century observers, but without the context of historiography they're criticism only succeeds at cutting down straw men. What we aim to do is to put this legacy in its deserved place, to understand the industry and concern that the authors imparted into their text, and uncover the noble art and glorious virtue therein.

Works Cited:

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo II (1500-1521). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo II (stumenti). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. History of Bologna Volume III. Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital.

Bianchi, Tommasino de. Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti. Italy, Pietro Fiaccadori, 1862. Volume 5. Digital.

Bianchi, Tommasino de. Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti. Italy, Pietro Fiaccadori, 1862. Volume 8. Digital.

Bianchi, Tommasino de. Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti. Italy, Pietro Fiaccadori, 1862. Volume 9. Digital.

Bianchi, Tommasino de. Cronaca modenese, di Tommasino de' Bianchi detto de' Lancellotti. Italy, Pietro Fiaccadori, 1862. Volume 10. Digital.

Häberlein, Mark. Dalhede, Christina. Kraftter; (Craffter, Krafter), merchant family. Wißner-Verlag, 2nd edition print edition. Wissner.com. https://www.wissner.com/stadtlexikon-augsburg/artikel/stadtlexikon/kraffter/4475https://www.wissner.com/stadtlexikon-augsburg/artikel/stadtlexikon/kraffter/4475. Web.

Sieh-Burens, Katarina. Oligarchie, Konfession und Politik im 16. Jahrhundert: zur sozialen Verflechtung der Augsburger Bürgermeister und Stadtpfleger, 1518-1618. Germany, E. Vögel, 1986. Digital. Heading 653.

da Bologna, Angelo Maria. Araldo nel quale si vedono delineate e colorite le armi de' potentati e sovrani d'Europa. Estense University

Emilio Orioli: Fencing in Bologna , in “Resto del Carlino”, 20-21 May 1901, n. 140

Alessandro Achillini, Humanist, Philosopher and Physician, Professor of Logic, Natural Philosophy and Theoretical Medicine (Bologna, 20 October 1463 – Bologna, 2 October 1512). Unibo.it. Link. Web.

Gelli, Jacopo. SCHERMA, Enciclopedia Italiana (1936). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/scherma_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/ Web.

Marozzo, Achille. Opera Nove de Achille Marozzo Bolognese, Maestro Generale de l'Arte de l'Armi. Modena: 1536. p ii.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Duel, or the Flower of Arms for Single Combat, Both Offensive and Defensive, by Achille Marozzo.” Lulu Press. 22 April 2018. Print.

Florio, John. Florio's Italian English Dictionary of 1611. N.p., Lulu.com, 2015.

ONCE SOVEREIGN HOUSES OF THE STATES OF ITALY; and national families descended from these or from foreign dynasties An historical and nobiliary essay. Review of the College of Arms. Year XX – 1922. Rome. PDF.

Emilio Orioli: Fencing in Bologna , in “Resto del Carlino”, 20-21 May 1901, n. 140.

He descended from a modest family of yccommoners originating from the nearby S. Giovanni in Persiceto and who in 1385 obtained Bolognese citizenship through two cousins. Our fencing master Achille Marozzo lived in Riva Reno in a house obtained in emphyteusis from the Abbey of Ss. Naborro e Felice where he lived and taught until 1553, the year of his death. As is known, he is the author of the first and most important treatise that was written in this type of thing, so that in a short space of years several editions were made: the first in 1536 in Modena by the abbot Don Antonio Bergola and then in 1546 in Bologna and subsequently in 1560 and 1568 in Venice. Marozzo dedicated this treatise of his to his fellow disciple Guido Rangoni, of which I would like to report here the opinion given by a very competent authority on the subject, the knight. Iacopo Gelli, who notes that Marozzo was the first to write about fencing with sufficiently defined and practical principles, so that he can be considered the true creator of Italian fencing which he raised to the highest level.

Ghirardacci, Della Historia di Bologna, Book III; Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. Pg. 220

“Il senato conduce per capitano delle sue genti d'arme , in luogo di Antonio Trotto , il conte Nicolò Rangone modenese , il quale a dì primo di maggio, il sabbato, venne a Bolo- gna et fu con molto honore dal senato ricevuto. Il signor Giovanni si pone in animo di dare al conte Nicolò Rangone.

Cullinan, Richard. "Marozzo, Achille, Opera Nova de Achille Marozzo Bolognese, Mastro Generale de l'Arte de l'Armi (Modena 1536) - Arte dell' Armi de Achille Marozzo Bolognese (Venetia 1568)". Lochac Fencing. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

Gelli, Jacopo. SCHERMA, Enciclopedia Italiana (1936). Treccani.it. Web.

Guido Antonio di Luca, come il Dardi suo maestro, fu protetto dai Bentivoglio, i quali ne frequentarono la scuola di via Saragozza a Bologna, ov'egli abitò sino alla sua morte.

Marozzo, Achille. Opera Nove de Achille Marozzo Bolognese, Maestro Generale de l'Arte de l'Armi. Modena: 1536. p ii.

Florio, John. Florio's Italian English Dictionary of 1611. N.p., Lulu.com, 2015.

ONCE SOVEREIGN HOUSES OF THE STATES OF ITALY; and national families descended from these or from foreign dynasties An historical and nobiliary essay. Review of the College of Arms. Year XX – 1922. Rome. PDF.

In the 14th Century the Bentivoglio were inscribed in the Corporation of the Butchers.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Della Historia Di Bologna. Italy, Giovanni Rossi, 1657. pg. 488

Giacomo Manzolino, Massaro de’Beccari

Ghirardacci, Della Historia di Bologna, Book III; Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. Pg. 349

“La notte seguente , a hore otto , venendo il lunedì , che fu il giorno solenne de ' morti , Giovanni Bentivogli si partì di Bologna con tutti i suoi figlioli legitimi et bastardi…Et con esso lui andarono parimente molti suoi intrinseci amici famosi di ricchezze et di prodezze, cioè:...Orabone dalle Agocchie , don Piero dalle Agocchie priore de ' Santi Cosma et Damiano et molti altri.”

Alessandro Achillini, Humanist, Philosopher and Physician, Professor of Logic, Natural Philosophy and Theoretical Medicine (Bologna, 20 October 1463 – Bologna, 2 October 1512). Unibo.it. Link. Web.

“His role as a renowned humanist intertwined with that as an indispensable courtier of the Bentivoglio court and a great supporter of the Università degli Artisti, in which Achilini was enrolled. This inevitably led to his escape when, in 1506, Pope Julius II regained possession of the city, sending not only Giovanni II and his family into exile, but also nobles and intellectuals who had been their supporters.”

Sieh-Burens, Katarina. Oligarchie, Konfession und Politik im 16. Jahrhundert: zur sozialen Verflechtung der Augsburger Bürgermeister und Stadtpfleger, 1518-1618. Germany, E. Vögel, 1986. Digital. Heading 653.

Zu ihm aüsfurlich: ChDst 32 S. IV-XI VII. Paulus Hector Meirs Vater ist mit Ursula Herbrot verheieratet. Er selbst heieratet Felezitas Kötzler, deren Scwester werdirun mit Wölf Hebenstreit verherietat ist.

Ludwig Hosers Witwe Sibylla Menhart heieratet 1532 (HB 352) Ulrich Jung: Jakob Kraffter heiritat 1540 Magdalena Jung.

Häberlein, Mark. Dalhede, Christina. Kraftter; (Craffter, Krafter), merchant family. Wißner-Verlag, 2nd edition print edition. Wissner.com. Web.

Um 1484 erwarb Lorenz Kraffter († 1521) das Bürgerrecht in Augsburg. Indizien weisen auf familiäre Beziehungen nach Nürnberg. Er wurde Mitglied der Kürschnerzunft. Der rasche Anstieg seines Anschlagvermögens von 200 (1484) auf 6200 Gulden (1516) lässt allerdings auf eine Tätigkeit als Kaufmann schließen. Seine Tochter Maria heiratete Jakob Hörbrot. Seine Söhne Hieronymus (I, * 1502, † 23.6.1566), Alexander († 1553), Jakob († 1554) und Christoph († 1588) waren Mitte des 16. Jahrhunderts erfolgreiche Großkaufleute und wurden 1548 vom Kaiser nobilitiert. Hieronymus unterhielt Geschäftsbeziehungen zum Kaiserhof, zum Herzog von Bayern und zum Heidelberger Hof, handelte mit Gewürzen und Textilien auf den Frankfurter und Leipziger Messen und hatte Verbindungen nach Antwerpen, Venedig, Bologna, Florenz, Lucca und Verona. Er belieferte die päpstliche Münze in Bologna mit Tiroler Silber und richtete 1556 in Bruneck (Südtirol) eine Messinghütte ein. Wegen unerlaubter Silberexporte nach Italien und der Einfuhr minderwertigen Geldes geriet er 1559 in Konflikt mit den Innsbrucker Behörden. Nach seinem Tod wurde seine Firma von den Söhnen Hieronymus (II, † 1597) und Anton († 1593) und den Schwiegersöhnen unter dem Namen ’Hieronymus Kraffter sel. Erben’ fortgeführt. Die Kraffter waren auch im Vieh- und speziell im Ochsenhandel tätig. ’Hieronymus Kraffter sel. Erben’ versorgte seit 1570 den Münchner Hof mit Ochsen. Hieronymus’ (I) Brüder Alexander, Jakob und Christoph betrieben eine gemeinsame Handelsgesellschaft, die Anfang der 1550er Jahre zu den aktivsten Firmen auf dem Augsburger Geldmarkt zählte. Neben Wechselgeschäften mit Antwerpen und Lyon betätigten sie sich vor allem im Textilhandel mit Italien. 1560 ging die damals unter Christophs Leitung stehende Firma infolge von Geldgeschäften zwischen ihm, seinen Schwägern David und Hieronymus Zangmeister und dem König von Frankreich bankrott. 1580 gehörten die Kraffter zu den Stiftern des Anna-Kollegs. Jakobs Sohn Lorenz (II) trat als Beauftragter Augsburger Handelsfirmen (u. a. Cristell und Pemer) in Venedig und auf den östlichen Märkten auf; 1599, 1600 und 1614 war er Konsul im Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venedig.

Animal Legends. Cornell University. rmc.library.cornell.edu/AnimalLegends/exhibition/destructionrebirth/trojanhorse.html#:~:text=After%20ten%20years%20of%20siege,thirty%20warriors%20led%20by%20Odysseus.

Ghirardacci, Della Historia di Bologna, Book III; Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital. Pg. 293

“Et Annibale frattanto fabricava un palaggio nel borgo della Paglia, nominandolo il Casino; et questo lo faceva per suo diporto et degli amici suoi, per potervisi et con l'arme esercitarsi et fare altre simili cose.”

1. In the paragraph after the first pic, you have "Filino dalla Tuata" instead of Fileno Dalla Tuata.

2. I love this type of micro-history, and I hope you keep writing and making podcasts about it.

3. Just imagine a film, or better yet a miniseries, centred around following key members of those families, each episode moving from one generation to the next to keep it simple and sweet.