The Holy Sword of Ludovico Bentivoglio

How Bologna came into possession of a Blessed Sword

Introduction

In the event you ever find yourself in the city of Bologna, you’ll no doubt want to visit the Museo Civico Medievale. There, you’ll happen upon a holy relic, the Blessed Sword of Ludovico Bentivoglio. This is the story of that sword!

The Blessed Sword

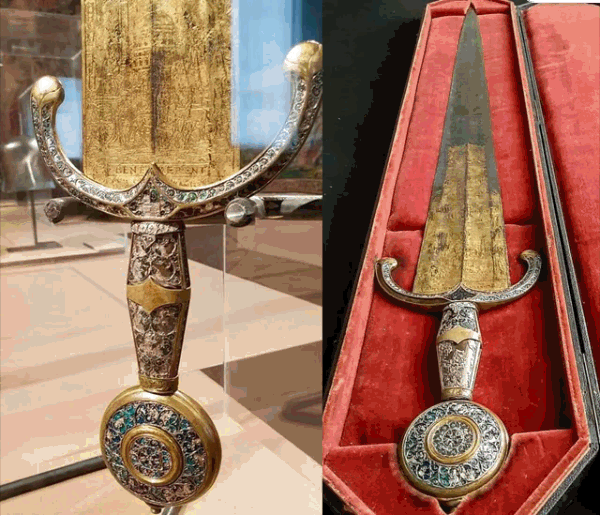

The Sword. A symbol of power, justice, courage—protection. Some swords have an epic story like Durendal, Hauteclere, Hrunting, or Excaliber. Others, were swords of state, handed down to rulers across the centuries as a passage of power. Yet still more, took on a claim to fame because of the exceptional abilities or legendary lives of their wielder, like Tizona and La Colada, the swords of El Cid, or Joyeuse, the sword of Charlemagne. In Italy and throughout Christendom, there was a fourth category of sword, the Holy Sword or Blessed Sword.

The Blessed Sword and Hat was a pontifical vestment bestowed on kings, emperors, princes, and dukes who by particular merit had, in the eyes of the church, proved themselves worthy of atonement.1 By church teaching, the sword did not offend, it protected justice, as espoused in a reflection by the 19th century philosopher and Christian apologist G.K. Chesteron, “A real soldier does not fight because he has something that he hates in front of him. He fights because he has something that he loves behind his back.” (Sonnen) In the age of the symbolic right of the Blessed Sword, this meant performing a military exploit against the enemies of the church, or other diplomatic acts closely linked to the policy of the Pontiff.2

These acts weren’t always as holy as they were made out to be. It’s hard to justify a list of supposed defenders of the faith, and soldiers fighting for something they love behind them, when Cesare Borgia is on the list of recipients. Therefore, one could reasonably argue, that as the political role of the Papal State evolved, the holiness of the vestment inversely declined—if it was ever holy in the first place.

It’s fascinating to see which Popes were keen on handing out Holy Swords, Pope Pius II, for example, gave ten swords to various kings, dukes, emperors, and doges across Europe, where the warrior Pope, Julius II; only gave out three, Alexander the VI; eight, Nicholas V; four, Sixtus IV; five, Calixtus III; two.

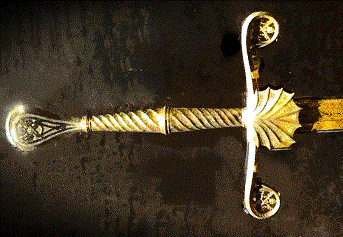

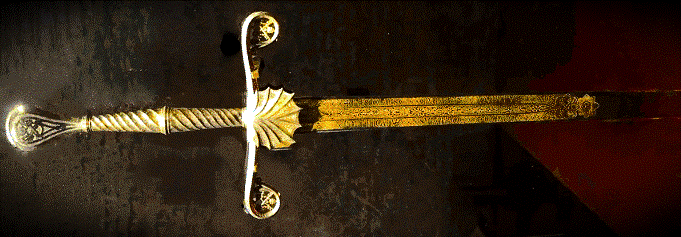

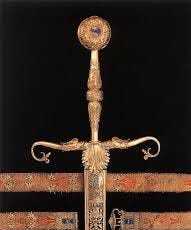

The swords themselves are beautiful, gilt, at times bejeweled, with amazing etching usually depicting the name of the Papa who bestowed the vestment on the blade, the coat of arms of the Holy See inscribed or inlayed in the pommel, the year and date it was blessed (usually Christmas), and the dove of the holy spirit inlayed in pearl. These magnificent creations were the work of the greatest artists of the age, Goldsmiths and Engravers, men like, Menardo Aurich, Bartolomeo Bulgari, Pietro Busdrago, Giovanni Paolo Cechino, Michelangelo Comunelli, Francesco da Santa Croce, Domenico da Sutri, to name a few.3 The final cost of crafting a holy sword would’ve likely varied, but the sword given to Ludovico Bentivoglio was valued at 150 Ducats according to Ghirardacci {$39,821.39 (US); by the value of gold (If 99.5% purity; ~24K) at 3.5g as of 5/12/2024}.4

Nomenclature of the sword is important to note here as well, as they were exclusively referred to as a Stocco in pontifical records, yet took on a number of different shapes and sizes; ie. various arrays of form show up across the centuries ranging from single handed swords, cinquedea, to two handed great swords. In my research, I can note a number of occasions of a Stocco being used in a number of different circumstances, from the battlefield, to the tournament lists, and in ceremony; eg. Fra Leonardo Prato and Luccio Malvezzi at the siege of Padua in 1509 preferring to fight with a stucco in armor, where Pirro and Lorenzo Malvezzi, Lorenzo Gozzadini, and Hettore Ghisilieri wielded a stucco at the Bolognese Carnival tournament in 1562. It’s a period typology or colloquialism we see a lot, but still has an unclear and unsettled association within the modern typological conventions. It’s easy to relate it directly to the English Tuck, or French Estoc, but it seems to have had a more varied connotation in the Italian sphere.

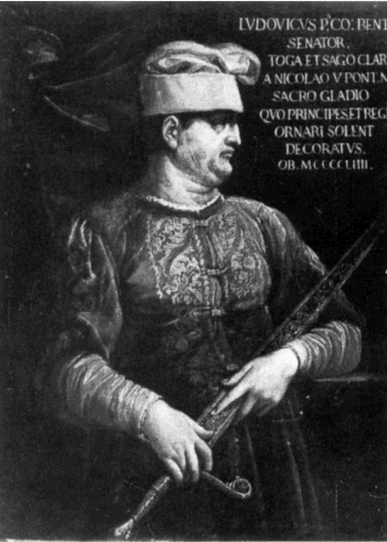

The tradition of the blessed sword and hat began in 1386, when Pope Urban VI, gave a sword and cap to Fortiguerra Fortiguerri, Gonfaloniere of the Republic of Lucca—though records of swords being given by Pontiffs date back to 1202 or 1365, depending on the reliability of source material—and lasted until 1825, when Pope Leo XII bestowed a Holy Sword on Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême.5 Out of the 81 Swords given over a presumed 600 year period, only four were given to someone without a title of authority (ie. king, duke, count, marquis ect.) or leaders of state, three of which were given to state entities, namely the Republic of Florence (2) and Switzerland (1), and the last one was given to Ludovico Bentivoglio.6

Who was this un-christened outlier? If you’ve been following along with our other series about the history of Bologna, you’re probably screaming at the elephant in the room— the Bentivoglio name—but there is more nuance here than that. Remember, while noble in Bologna, due to trade/profession and family status (knight, doctor, or noble guild), that authority was inherently regional. The Pope would change that, and knighted Ludovico when he gave him his hat and sword, but prior to that point, this was a man who for all intents and purposes, by his own merit, could’ve been a footnote in history. So, why him? What made Ludovico Bentivoglio special?

Dramatis Personae

Bentivogleschi: or the Bentivoglio Faction; comprised of loyal Bolognese families committed to the seignorial reign of the Bentivoglio family; typically represented by the Marescotti, Malvezzi, Pepoli, Fantuzzi, Ghisilieri, Sanuti, and Viggiani to name a few.

Caneschi: The Canetoli Faction; comprised of loyal Bolognese families committed to the seignorial reign of the Canetoli family. The Canetoli were supreme in Bologna between 1421-1434, and long to reestablish their dominance over the city. Represented by the Canetoli, Mezzovilliani and Ghisilieri primarily. The Caneschi were the mortal enemies of the Bentivogleschi.

Ludovico Bentivoglio: Born to a junior branch of the Bentivoglio family, he served as a faithful and level headed civic leader in Bologna, often seeking reconciliation and diplomatic initiatives over vendetta and bloodshed.

Luigi dal Verme: A Condottiere in the employ of Niccolò Piccinino and Filippo Maria Visconti. A veteran mercenary captain and the son of the famous Iacopo dal Verme who served under the Sforzesca and Venice before seeking employment with the Visconti in Milan in 1436.

Battista Canetoli: The leader of the Canetoli faction in the mid-15th century. He was exiled from Bologna in the 1430’s, and eventually imprisoned by the Visconti during the reign of the the Piccinino in Bologna.

Lodovico Caccialupi: A stalwart diplomat of the Bentivogleschi. Caccialupi had a doctorate in law, and wielded his expert knowledge of both civic and cannon law to shield the establishment of a permanent Bentivoglio Signoria.

Sante Bentivoglio: The bastard son of Ercole Bentivoglio who was the brother of Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio. Sante was raised as the son of a blacksmith, and was eventually adopted into a rich Florentine family, that set him up with an apprenticeship as a wool-merchant. Upon the death of Annibale Bentivoglio, he was plucked from the life he knew, and propped up as the leader of the Bentivoglio faction until the son of Annibale Bentivoglio, Giovanni II, came of age.

Galeazzo Marescotti d’Calvi: After spending his youth in the Condottiere company of Francesco Sforza, he returned to Bologna in 1438 with Annibale Bentivoglio. Often the muscle of the Bentivogleschi, he was known for his no-nonsense, quick to violence nature, and excellent leadership abilities.

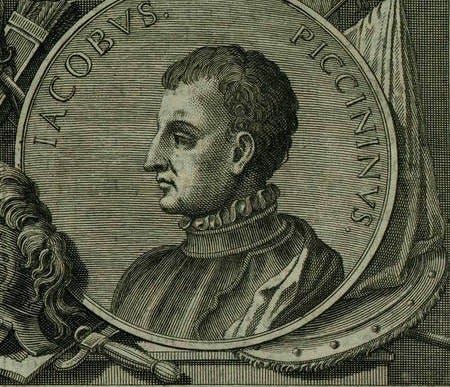

The Piccinino Family: Niccolò Piccinino took over Braccio del Montone’s mercenary company in 1424, after the battle of l’Aquila, and used it to carve out a small empire for himself in northern Italy in the 1430’s. His territorial holdings included Bologna, after a coup in 1438, led by Raffaello Foscarari. His son’s Francesco and Iacopo took up their father’s profession, and after his death in 1444, tried to keep his mercenary company together.

Francesco Sforza: The son of the legendary condottiere Muzio Attendolo Sforza, he was one of the most capable and competent military commanders of the mid-15th century, and the great rival of Niccolò Piccinino. Thanks to a smart marriage alliance with Visconti, and the political machinations of Cosimo de’ Medici, he became the Duke of Milan, and established the Sforza dynasty.

Pope Nicholas V: Tommaso Parentucelli studied theology at the Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, where he graduated in 1422. After completing his studies he spent the next two decades traveling Europe to further his studies, taking part in the councils of Basel (1431), Ferrara (1438) and Florence (1439) before becoming the legate of Bologna in 1444, and pope in 1447.

Ludovico Bentivoglio: Background

Born in the last decade of the 14th Century to Carlo Bentivoglio and Bartolomea Guastavillani, Ludovico would have a quiet start to his life in Bologna.7 Reasonable considering the violent death of his uncle Giovanni Bentivoglio in the first decade of his life, but interesting due to the proactive fervor of his cousin, Giovanni’s son, Antongaleazzo between 1416-1424. The first we see of Ludovico, is a note in 1428 that he facilitated the reconciliation between, Pope Martin V and Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio, where he convinced the exiled lawyer-turned-condottiere to go to Rome and kiss the perturbed Papa’s feet.8 That same year he was elected into the Sedici, or the Sixteen {the Senate of Bologna}.9 However, his time in the Bolognese government would be short lived, as he was exiled by the Canetoli a few months after his election, when they acted on some intel about a suspected Bentivoglio coup, and he wasn’t allowed to return until 16 March 1430.10 This return wouldn’t last long, as Ludovico found himself getting tossed from the city of towers once again after a dust-up between Bentivoglio supporters and Canetoli cut-throats in April of 1430, which broke the terms of truce and led to another forced exodus of Bentivogleschi from Bologna.11

The next time Ludovico would see his home city again was in 1438 when he returned to Bologna with the retinue of Annibale Bentivoglio.12 Upon his arrival, Ludovico was brought into the Dieci di Balìa {a governing body that briefly replaced the Sedici} by Raffaelo Foscararri, as a way of preventing Annibale Bentivoglio from holding any government positions. As we’ve seen, Foscararri’s ill fated attempt to make himself Signoria didn’t quite pan out, he ended up dead on the cobbles of the via Clavature. Murdered by the ambitious Annibale and his Bentivogleschi allies.

Under the new alliance between Niccolò Piccinino and the Bentivoglio party, Ludovico worked to reconcile the Bentivoglio and Canetoli factions (who Foscarari had brought back to weaken the Bentivoglio power in the city—unbeknownst to Ludovico).13 Despite being exiled by the Canentoli twice, Ludovico always worked as an intermediary between the two families—that’s why he was allowed back in 1430—but it’s worth noting that his actions here would have unforeseen consequences later on.

After the capture and imprisonment of Annibale Bentivoglio in Castello Varano, followed by his incredible escape—thanks to the daring of Galeazzo Marescotti, and the overthrow of the Piccinino government in Bologna, Ludovico Bentivoglio was granted the governorship of Cento.14 Unfortunately for Ludovico this put him right in the crosshairs of the Milanese captain Luigi dal Verme when he heeded the covetous war-call of Filippo Maria Visconti, the Duke of Milan, and his disgruntled condottiere-ally Niccolò Piccinino.

From Cento With Love

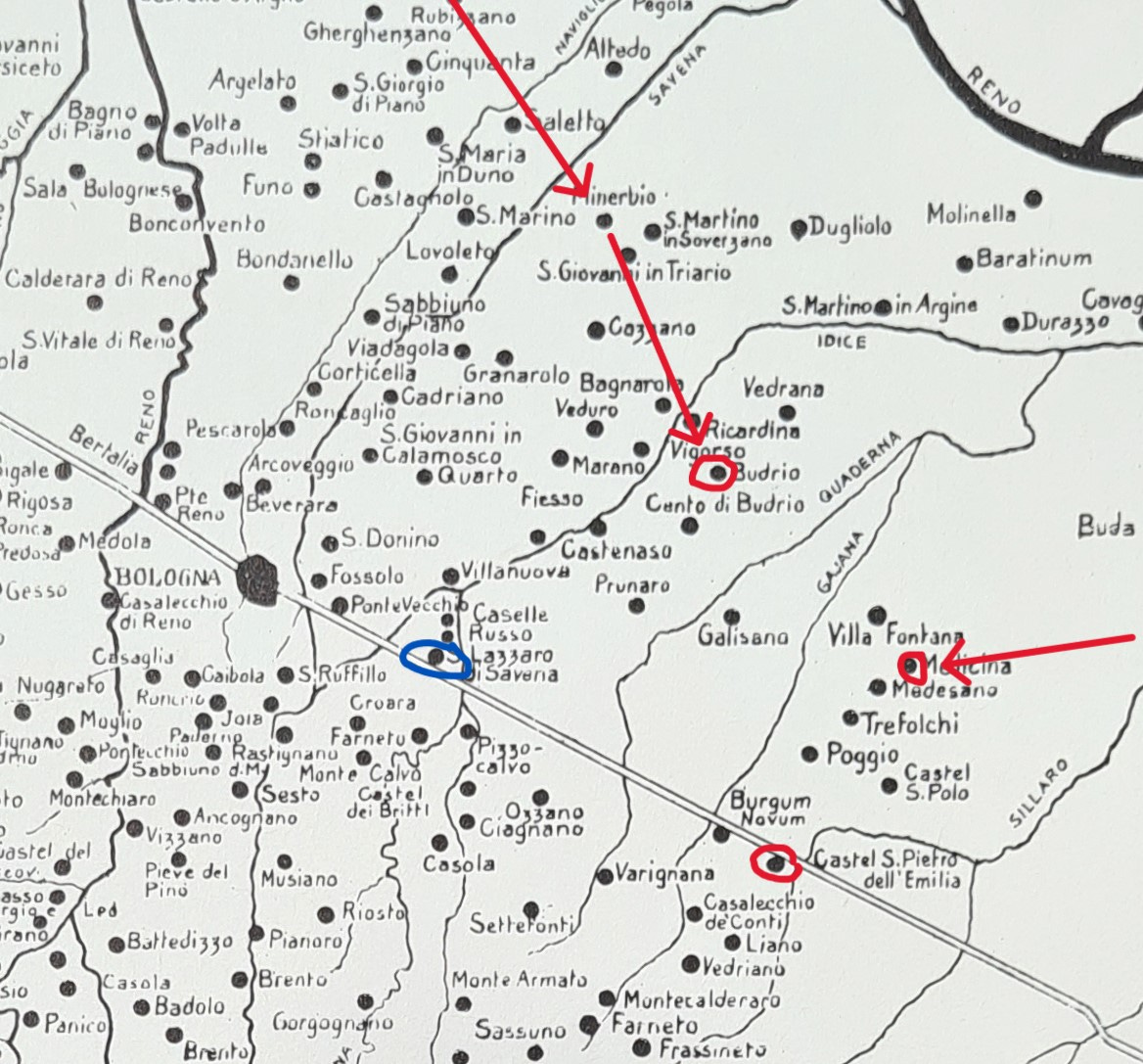

When the Bolognese people drove Antonio Manfredi out of of Bologna in 1443, and ruined Luigi dal Verme’s plans for a quick capitulation of the city, he decided it was time to make his presence felt in the contado {countryside}. On behalf of Niccolò Piccinino, Luigi had letters distributed to all the rural castellans of Bologna. The cities of Budrio, Medicina, Castel Guelpho, Minerbio, San Giorgio, Argelè, and Pieve di Cento were all recipients of these correspondence, and decided that they didn’t want to take their chances, so they gave up the gates as soon as they received the request to surrender.15 The one holdout was Cento, because Ludovico Bentivoglio was loyal to his family. On the 8th of June 1443, Luigi dal Verme decided to test that loyalty, and showed up on the Centani doorstep with his entire army, and demanded that they change their minds and surrender.16 The people of Cento could’ve given up the gilt, turned Ludovico over to Luigi for a fat ransom, and skated through the first act of yet another war, but instead they decided to take up arms and blocked the streets of the city—they too were loyal.16

Luigi was disappointed, he was hoping they’d take the gold, and he’d have a nice new bargaining chip for his negotiations with the Bentivogleschi faction now ruling Bologna. Instead he’d have to fight, and boy did the Centani put up a fight! Dal Verme’s men managed to break into the fortress of the city, and made their way into the streets of Cento. Desperate fighting ensued, with numerous casualties beleaguering both sides, but dal Verme’s troopers grossly underestimated the dogged determination of the Centani people, and were eventually driven out of the city in shame. Ludovico, for his part, led his troops from the front, and was wounded in the leg during the course of the fighting.17

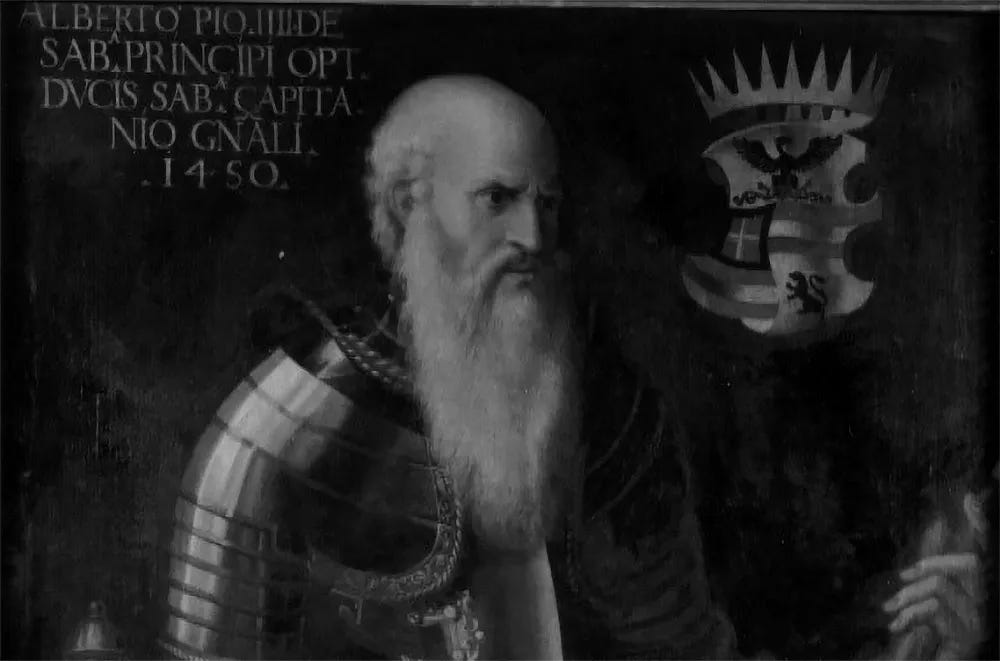

Once the dust of the first assault settled, Ludovico and his Centani captains sent urgent letters to the Lord of Carpi, Alberto Pio, to hurry with the 200 cavalry that he had promised in support of their efforts, but when the Lord of Carpi’s forces approached the city, and saw the size of dal Verme’s army, they decided join the enemy camp, rather than keep their word.18 This was a serious blow, and Luigi dal Verme could sense it, he sent new messages demanding the surrender of Ludovico Bentivoglio—or else.19

The Centani leaders approached Ludovico, and explained the difficult situation they were in. They asked him to have patience, and to forgive them for what they were being forced to consider.20 To which Ludovico replied, “Well, honorable brothers so loved by me, I beg you not to make such a serious mistake, but have respect for my house and some consideration for my rank. To you, if you want to save me, I promise upon my faith that I can give you 10,000 gold ducats, with a suitable promise for each of your petitions.”21

This was a generous offer, the Centani leaders huddled up, and deliberated about what to do next, then came back with a plan. They were going to try to satisfy both parties. They would take the 10,000 ducats promised by Ludovico and offer it to Luigi dal Verme, in hopes that he would leave them alone.22 Messengers left Cento and arrived at dal Verme’s camp, they laid out the details of the offer to Luigi, but the count wasn’t interested, he scoffed, and replied, “I don’t need your money, I wasn’t asking for money, I want Ludovico Bentivoglio!”23

Weary messengers brought the counts rebuff back to the Castello. Ludovico, being the silver tongued sly-fox that he was, let his sadness and disappointment show. This disturbed and rather guilty Centani leaders, so they decided to give him some time alone to collect himself out of respect, and that was the space Ludovico needed to escape!22

Ludovico, who was still reeling from his wounds, climbed out of the window, and lowered himself down into the moat of the Centani Castello, then swam across the murky water and slithered through the dense mire-laden ditches, down into the second moat, to emerge on the other side exhausted, afraid, and covered in mud. Aware of what was at stake, he limped his way, some 39 km to Carpi, where he hoped to find safe refuge, and laid low while things unfolded back in Cento.23

The Centani leaders were shocked to find that Ludovico was missing from his room, surely they couldn’t help but admire the brazen Bentivoglio’s sprezzatura, but their lives were now in serious danger, and they were forced to come up with a hasty plan B. When they emerged from the fortress to meet with dal Verme, they disclosed everything, and offered bread, wine, and fodder for his entire army, along with five hundred gold florins as recompense for their misfortune.24 Fortunately for the city of Cento, this was enough for Luigi—all he wanted was Ludovico Bentivoglio.

While his troops supped on the spoils from Cento, Luigi devised a new plan to capture Ludovico in Carpi. His first thought was to bribe Ludovico's father-in-law-law, Gasparo Malvezzi—who was still locked in a prison cell—with money, status and freedom. But Gasparo wasn’t interested in playing ball, and tersely replied to Luigi’s offer with, “I would rather die in the dark prison than betray my son-in-law whom I love.”25

Luigi kept scheming—then it struck him, he had Battista Canetoli in a prison cell as well, and he knew that ol’Ludovico was sympathetic to the Canetoli cause. So, he made Battista an offer he couldn’t refuse, his freedom, and a promise that no patrician of his house would ever rise to such a sublime level, if he brought him Ludovico Bentivoglio in chains—Ah ambition!26

Battista took the bait.

The Carpi Conspiracy

Battista was escorted from Cento to Carpi by Giacomo da Imola, and 300 men from Luigi dal Verme’s army.27 On the ride through the Emilian countryside Battista started dispatching letters to Ludovico Bentivoglio, letting him know that he’d been released from prison, and that he would love his company on the road to Modena.28 Just an old friend looking for a travel companion, nothing too outlandish. Except—Ludovico knew how to sniff out a rat. He replied that he was happy to hear about Battista’s liberation, but that he was very sorry he wouldn’t be able to accompany him on the road to Modena because he had been wounded in the leg in Cento, and even if he could muster the energy, he would still be without the requisite finery and resources to act as a proper companion for such a dear—and trusted friend.29

Battista stopped in Correggio, and sent another letter, this time shirking the lure of a tenuous ride, for a nice simple meal with a road-weary sojourner in need of good company, but Ludovico was on to his game, and replied that he was still unwell.30 Battista was not dissuaded, and moved his coalition close to the the boarder of Carpi, where he sent a third letter, this time to the Carpesian lords, letting them know that he was coming into town, and would like an audience.31

Battista, his escort Giacomo da Imola, and 12 other horsemen rode into town while the remainder of the company stayed outside the walls where they couldn’t be seen.32 Battista's retinue were treated as honored guests by their Carpesian hosts, and Ludovico was forced by the rights of courtesy to present himself for their arrival.

After Barttista’s grand entrance, the cunning Canetoli pulled his Bentivoglio friend aside, and asked him to join his merry band on the road to Bologna.33 It’s clear what Battista’s angle likely would have been here; long had Ludovico worked to reconcile the two great Bolognese houses {consequently as they spoke in Carpi, legislation was being debated in the Bolognese Anziani around the terms of a Canetoli faction return from exile}, this would be a seminal statement that could bring the healing and unification that Ludovico desired. But—Ludovico was wise to the deception, and politely declined.34

Battista understood, and said it would be enough for Ludovico to at least accompany him out of Carpi.35 Ludovico simply shook his head and said, “Battista, I marvel at your persistence, that you would first request that I accompany you to Bologna with your companions, then somewhere not far outside of this land, but I am even more amazed that, being a wise and prudent man, as you shown throughout your life in important matters, that you still don’t want to hear my apologies for not wanting to join you, as you clearly can’t see, that I, like you, don’t want to be imprisoned and therefore don’t want to step outside of this place. So please understand why I don’t think it’s wise to keep you company.”36

Battista’s face flushed, and he apologized profusely, then reassured Ludovico that he was ashamed that he had aroused such an arduous suspicion, but his intent was never to betray him to his enemies, it was always for the pleasure of his company. Sullen and defeated, realizing Ludovico wouldn’t budge, he told him to go with God, and left.37

The Carpesian lords gave Battista a beautiful new horse as a gift for the road ahead, but he knew what was coming, so he rode his magnificent Carpesian stallion over to Ludovico, who was in attendence to bid the honored guests farewell, and asked his friend for one last favor. “Ludovico, my friend” he said, “can you have one of your loyal servants follow me just outside the city to take care of this wonderful new gift that our gracious hosts have bestowed upon me?”38

Ludovico obliged. When Battista and his company arrived at the place where their 300 men-at-arms were waiting. Giacomo da Imola had Battista dismount from his prized stallion, clapped his hands in irons, and put him on a sad old nag.39 The soldiers were cruel to their prisoner, taking every non-submissive gesture as a cause for a fresh beating.40 Battista looked up through swollen eyes at Ludovico’s servant, atop his beautiful new charger and said, “Go in peace, and recommend me to your lord.”41

The sullen servant returned to Carpi, and related what he had witnessed to the Carpsian lords and Ludovico. Bentivoglio crossed himself and said, “I always imagined all this would happen and therefore I never gave up, even as he begged, for which I will be forever be thankful to God.”42

The Afterblow

In course, Luigi dal Verme’s army was undone by Carpesian spies in his camp feeding information to Ludovico, who relayed their movements to Annibale Bentivoglio in Bologna, leading to the devastating defeat of dal Verme’s army at the battle of San Giorgio.43

Upon the destruction of dal Verme’s army, Ludovico finally returned home, in August of 1443. He played a key role in the establishment of the permanent Bentivoglio signoria, laying the legal foundation for the familial dynasty that was to come.44 Good news reached Bologna when Niccolò Piccinino was recalled to Milan, and left his Bracceschi company in the hands of his son Francesco, who was summarily defeated and taken prisoner at the battle of Montolmo, in February of 1444, by Francesco Sforza;45 this defeat and Niccolò Piccinino’s sudden death in October of that year, were serious blows to the dynastic enemies of the the Bentivoglio family, and a cause for celebration in Bologna.

In 1445 Ludovico Bentivoglio was elected into the Sedici, or the Council of 16 Reformers. All was well in the city of towers, until his ‘friends’—the Canetoli, grew jealous of the preeminence of the Marescotti d’Calvi faction, resulting in a tense, brutal blood feud between the two families that engulfed the city for the better part of a year {We’ll cover this in detail in a future piece}. This violence inspired Battista and Battozzo Canetoli to plan a murderous takeover which resulted in the death of Annibale Bentivoglio, and all of Galeazzo Marescotti’s brothers.

In the wake of this tragedy, Ludovico Bentivoglio was approached by Galeazzo Marescotti and the other leaders of the Bentivogleschi, who asked him to assume leadership of the faction, but Ludovico knew better; of the main Bentivoglio line, Annibale, his father Antongaleazzo, and his grandfather Giovanni had all been violently murdered. Ludovico wasn’t born into that legacy, and he didn’t want to will himself into it either.46 He was happy to support the family in whatever way he could, but he wasn't about to put his head on the chopping block for ambition. Lodovico did step up in a different way however, he became the Gonfaloniere di Giustizia in 1446, assuming civic leadership of the city.47

Pope Nicolas V (Round 1)

Ludovico Bentivoglio, Lodovico Caccialupi, and Galeazzo Marescoti all played huge roles in helping to stabilize the Bolognese government under the reign of the new regent Sante Bentivoglio. On 11 April 1447, when Pope Nicholas V ascended the throne of St. Peter, Ludovico Bentivoglio was a part of the ambassadorial cohort that went to Rome to welcome the new vicar, and petition the pontiff to officially recognize the new republican government under Sante Bentivoglio. The diplomatic committee was comprised of Melchiorre Viggiani (knight), Nicolò Sanuti (knight), Battista da Castel San Pietro (doctor), Gasparo dalla Renghiera (doctor), Lodovico Bentivoglio, and Melchiorre Malvezzi.48

They waited-and-waited for official word that they would be permitted to see his holiness, and finally on the 27th at 2pm they got their invitation to petition the pontiff.49 The ambassadors presented their case and implored his holiness to see the virtue of recognizing the sovereignty of the Bentivoglio signoria, to which Nicolas replied that he longed to see a free and independent Bologna, but that the matter would need to be negotiated in court. As such, the Anziani recalled a portion of the ambassadorial committee, and left Nicolò Sanuti, Battista da Castel San Pietro, and Ludovico Bentivoglio in Rome to present the case before the curia.50

The opening salvos of the negotiations were looking bleak for the presiding Bolognese councils, they just couldn’t get their final proposals across the finish line, so the Anziani decided to send their closer Lodovico Caccialupi to Rome. Caccialupi left Bologna on the 14th of May, and upon his arrival brought his expert legalese to bear. The deals closed with favorable terms for Bologna, and Lodovico Caccialupi was made a Golden Knight of the Pontificate as a result.51

While things seemed finalized in Rome, the terms of the agreement were a bit perplexing to the presiding councils back in Bologna when they were finally presented with the details by the new Papal Legate, Agnesi della Spada, Bishop of Benevento on Friday, the 15th of September.52 {If you don’t want to read through this next part, skip ahead, I’ll highlight the important parts.} Here are the charters:53

By divine clemency Pope Nicola V, on behalf of the lords orators of Bologna on behalf of the community of Bologna; with whom chapters, the recorded applications and supplications our most serene Lord commands, wishes and declares the below-mentioned answers and signatures to be made in all the below-mentioned chapters, as is contained at the end of them and at the end of each one of them: the tenor of which is such:

That the people of Bologna render obedience to the pontiff with a promise to observe his will, and they beseech His Beatitude to forgive them for all their errors committed against the apostolic see up to the present and to absolve each level of person from every censure and every other thing leveled against them, privation of offices and benefits, and which totally annihilates and erases anything and reduces it to its original state;

That they hand over all jurisdictions to His Holiness and assign them with the following chapters; and thus to his Beatitude they assign and give the city of Bologna with all its surroundings, territory and district, castle, lands, villas and places, and they swear and promise loyalty and obedience to his Holiness, according to the tenor of the chapters below; that is, that every person of the city, county and district of Bologna, who was obligated in some quantity of money to the pontiff or to the apostolic chamber, shall be absolved and freed from any quantity of said money and from any debt which they had purchased from the year 1438 on the 20th of May up to the present day for the regiments and officials of the municipality of Bologna;

That the lords of Anziani can be made Gonfalloniere di Giustizia, leaders of the people and masters of the arts (massari delle arti) according to custom, and have the Podestà, according to the form of the city, and that the lords of the Sedici are created, who together with the legate have to govern the city for all his offices; which once finished, together with the legate they must elect other members of the Sedici, who together with the legate have to create a Gonfalloniere di Giustizia, and that all the said magistrates cannot conclude anything without the legate, nor the legate without the regiments;

Should the lords of Anziani and the Sedici wish to send any embassy to the pontiff or the lordship of Venice or the Florentine lords, they may do so as much as seems appropriate and necessary to them, and this should be done by common counsel; and there is no intention of “sending to the Pope, which they can send without the advice of the legate; " " May the embolism of the offices carried out for the regiments of Bologna not continue until " it is finished . Then the Sedici with the legate must renew it according to the majority's opinion and that the vicars who will be sent to Cento and to the Pieve must swear loyalty in the fealty of the bishop or others appointed by him, and once this emboss is finished " the action of the vicars, it belongs to the bishop to carry out the new embolization of said vicars;

That every citizen or farmer of the municipality of Bologna who has any assignment from the chamber of Bologna be satisfied by the said chamber, if said assignment" is done correctly, and that from month to month the money must be extracted for the expenses necessary for the governing and government of Bologna, and whatever is left over will be paid to the said creditors of the said chamber; by which appeals are made to one of the judges:

That the legate and the lords of Anziani should stay in the palace, the legate electing that part of it that he likes most, and the lords of Anziani should live in the other part as long as this "pleases the pontiff”;

That if anyone makes a donation, no remission should be made to him either for the legate or for the lords of the city, but the form of the statutes of the city should be observed. And that the municipality of Bologna is obliged to pay the legate every month five hundred lire of bolognini as his salary, and that all matters are dealt with by common council;

That the people of Bologna have the discretion to lead soldiers on foot and on horseback as much as they like, at the expense of the municipality, which soldiers must swear loyalty in the hands of the legate and the Gonfalloniere di Giustizia;

That the office of the treasurer of the chamber of Bologna remains as it is now found, "since it was established six years ago, the pontiff appointing a treasurer with a salary of 300 florins a year to be paid for the chamber of Bologna , and that all other usufructs " reach the said treasurer ;

That the lords of Antiani , Gofaloniere di Giustizia, Gofaloniere di popolo, Massari delle Arti , Podestà , Giudice della Mercantia (Judge of the Merchants) and all the other officials must swear loyalty in the hands of the legate;

"That all the letters from the offices of Bologna and the countryside, with all the entries that will be made in the chancery, cannot be made, nor are they valid, if they are not made by the hands of the chancellors of the legate, as per those of the lords of Anziani;

That if any lord or lordship wages war against the city of Bologna, the Pope is obliged “to give subsidy, help and favor to the city for its defense.”

Once the said chapters were published, the governor and everyone who was in the council came out and went to their homes. The Pope having already made some chapters with the city of Bologna, the orators being Melchior de 'Vizzani a knight, Gasparo dalla Renghiera a doctor of law and Melchior de 'Malvezzi a citizen of Bologna, he once again confirmed the said conventions, chapters and pacts.

There are a lot of really interesting details in this charter, things that relate back to events of the past; eg. the tesurarii getting their loans to the city repaid by the curia, and important details that will come to bear in the subsequent narrative of Ludovico Bentivoglio’s life, eg. That if any lord or lordship wages war against the city of Bologna, the Pope is obliged “to give subsidy, help and favor to the city for its defense.” and “Should the lords of Anziani and the Sedici wish to send any embassy to the pontiff or the lordship of Venice or the Florentine lords, they may do so as much as seems appropriate and necessary to them, and this should be done by common counsel.”

Upon further examination of the terms, a number of the skeptical civic leaders realized what a resounding success the charter was, as the Pope was limited by law, they were granted the rights of protection, and more importantly they were no longer ecclesie immediate subjecta. However, it still had some hardened detractors, and the metal of the initiative was tested early after it’s adoption in 1448.54 Turbulence with remaining rebels of the Canetoli faction in the contado led to Agnesi della Spada condemning the reciprocal violence between the two factions plaguing the city and the countryside, in detailed letters to the pope.

In response to this perceived overstep Galeazzo Marescotti and Sante Bentivoglio threatened the legate with defenestration.55 The podestà {ie. Chief justice, Police captain, or Attorney General} drew the ire of the Bentivogleschi too, when he tried to impose a weapons ban on the city with an associated fine of 10 lira per violation; which was also met with a not-so-subtle threat of defenestration.56 In response to this brewing chaos Agnesi della Spada called the Anziani to council and demanded direct rule of the city in the name of the Pope—which didn’t materialize, with Santi Bentivoglio, Ludovico Caccialupi, Ludovico Calvi, Barolomeo Lambertini, Battista da San Pietro, Cristoforo Caccianemici, Romeo Pepoli and Giovanni Fantuzzi presiding, so Agnesi decided to tuck-tail, and get the hell out of Dodge—or retire to the baths of Siena, as he put it.57

Fracturing Factions

In the wake of della Spada’s swift exit, he left Filippo di Guido Pepoli, General of the della Crociati58, or the crusading order, in charge as vice-legate.59 The Plague struck the city hard in 1449, and many of the citizens who could—fled; leaving Bologna a ghost-town. This gave the Caneschi exiles in the contado {the Canetoli and Ghisilieri at this point} hope that they could capture city, since most of it’s civic defense was dependent of it’s ability to call upon it’s citizen militias.60 They hired Astorre da Faenza to attack Bologna, but the remaining Bentivogleschi were armed and prepared.

During the course of the preceding assault on Bolognese territory, and subsequent tumult spurned by further factional politics in the city, a number of atrocities riddled the municipality, as the militant wing of the Bentivogleschi had full control of civic affairs. Sante Bentivoglio was pushing for too much power, and putting pressure on the vice-legate, Filippo di Guido Pepoli, to facilitate his every demand to deal with the rebels; namely, executions without due process. Filippo eventually had enough and left Bologna for Rome to make an account before the Pope of all the misdeeds that he had witnessed in city.61

It wasn’t just the Pope’s men who were storming out of the city, however, the Bentivogleschi faction was starting to fracture as well. Sante, from a diplomatic perspective, was keen on following the lead of Francesco Sforza, his mentor, and Cosimo dei Medici, his former patron. For some, it seemed that Bologna had become a vassal state of Florence under the Florentine born Sante’s rule. So, after the exit of Filippo di Guido Pepoli, his brother Romeo Pepoli, gathered together a council of concerned Bolognese nobles, many of whom were long standing loyal members of the Bentivogleschi faction; Nanni Viggiani, Giacomo and Giovanni Fantuzzi, Alberto and Nicolò Musotti, among others, and had the following discussion:62

Romeo, turning to his friends, began to complain greatly about Sante Bentivoglio, that the primacy of the city had been so recklessly usurped, having been called to act as regent for Annibale’s son Giovanni and not to oppress or denigrate it’s citizens, yet due to his desire to elevate himself above all others, that as his greed and ambition were not catered to, the affairs of the city and the citizens would turn from bad to worse.

After a long discussion on this, they concluded that it would be best to make a contingency plan and seek council as to not incur a bad outcome. Nanni Viggiani approved of what Romeo had said, and confirmed, that in his private conversations with Sante, he had confessed such evils, and it was either necessary to patiently wait out his reign, or spontaneously go into exile, but he would leave that decision on what course of action to take, to the opinion of those wiser than he.

Then, Giovanni Fantuzzi spoke up and said that his opinion was to leave the city and move to Castello San Pietro, for fear of the plague, and want of fresh air, then having gathered there, they could arrange what would seem like an expedition with the King of Naples, who was in Romagna, then together with the Canetoli and other Bolognese exiles, drive Sante out of the city.

This opinion of Giovanni’s was agreed upon by all, and little by little they left the city under the pretense of fighting the plague.

—Ghirardacci Book III, pg. 130-131

The rebel faction took control of Castello San Pietro, in early August, and sent urgent letters across the Emilia region to the fractious remains of the Caneschi, as well as the Pope begging him to recognize their forthcoming coup, and the vice-regent of Naples asking for much needed military support.63 All of this remained out of the purview of the Bolognese government until the locals who helped the rebels capture the city of Castello San Pietro were identified, captured, and brought back to Bologna where they were tortured and condemned to death. While in custody they confessed to the conspiracy, and named Giovanni Fantuzzi along with his brothers, Nanne Viggiani and his brother, Giacomo Fantuzzi, as well as Alberto and Nicolo Musotti as the chief proponents of the plot, before being beheaded. Sante responded by exiling the named cohort, destroying their palazzos, and hiring Astorre Manfredi, to enter the city with 600 well trained knights, in hope of reclaiming the castello in the name of Bologna.64

Good news came for the rebel faction quite early in their ascendency, the Pope heard and understood their plight, he was tired of the violence in Bologna, and more than a little concerned about the second city of the Holy See aligning so closely with the powerful northern Italian alliance of Milan and Florence, and was therefore—concerned about his flock. In the contado, Crevalcore was the next township to fall to the rebels when Giacomo and Opizzo Pepoli, the sons of Guido Pepoli—who had been in the vicinity to avoid the plague—raised an army of 200 men and convinced the garrison of the castello to capitulate in favor of the rising faction.65 Pietro di Giovanni Fantuzzi also capitalized on the prevailing chaos and made an attempt to capture Piumazzo, but upon entering the settlement and thinking his job of neutralizing the opposition was accomplished, found himself undone when his men met a force of the remaining garrison and armed citizens that had gathered to drive him out, chanting ‘Long live the church!’.66 Fantuzzi’s entire force collapsed and he was captured, ending any hope of the rebels securing the settlement. Word of the heroism of Piumazzo reached Crevalcore and inspired the people and the remaining garrison to do the same. On 11 September they gathered together and started marching through the streets shouting, ‘Long live the church and the people of Bologna!’, and dislodged Giacomo and Opizzo Pepoli from the city.67

With word of the rebel factions setbacks in the contado reaching Sante, he decided it was time to capitalize on the moment, and go on the offensive, so he dispatched Astorre Manfredi with a portion of the Bolognese militia to attack the remaining rebels in Castel San Pietro. Before Manfredi could arrive, the Castello San Pietro garrison was bolstered by a detachment of infantry and much needed supplies from the vice-regent of Naples, Count Carlo da Compobasso. When Manfredi arrived, he quickly realized he needed more men, and sent word back to Bologna. Sante responded by sending ten men from every castle and fortification in Bolognese territory {likely around 700 men total—based on the number of castellans assigned in similar timeframes}. 68

While Astorre awaited his reinforcements from the city, he took the Bolognese army north and secured the city of Medicina, before returning to San Pietro.69 Then, on the 27th of October, Manfredi, and his civic councilor, Achille Malvezzi, started the assault on the rebel faction. They rocked the city walls with bombard blasts, day and night, which reduced a third of the cities fortifications to rubble. Realizing that time was running out, the rebel faction dispatched diplomats to treat with Achille Malvezzi, and started negotiating an amicable surrender to prevent Astorre’s men from storming the breach. Their ruse worked. After long, arduous and drawn out negotiations, on the 27th of November, the vice regent of Naples sent a herald to challenge Astorre Manfredi’s army to battle.70

Urgent dispatches flooded into Bologna, the Anziani and Sedici both agreed that they had no choice but to retreat from Castel San Pietro, and ordered Manfredi to pull his men back to San Lazzaro di Savenna, along the Via Emilia {16 km; 10 miles NW}, to fortify the left bank of the Savenna river at the Maggiore Bridge.71 As Manfredi’s men-at-arms were digging in, spies in Ferrara brought harrowing news from the north— Ludovico Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, had requested permission to cross Ferrarese territory with 5,000 more men. The Bolognese army was about to get caught in pincer with no conceivable way to raise a substantial force quick enough to contend with the combined armies of Mantua and Naples {A census in 1450 concluded between 14-16,000 people were missing from the city after the plague72}. In the palatial halls of Bolognese authority there was no doubt that his was the retribution of none other than Pope Nicolas V!73

As Gonzaga’s army, comprised of 3,000 cavalry and 2,000 infantry, pressed into the the contado from the northeast, securing Malacompra, Minerbio and Budrio; Compobasso, the vice-regent of Naples captured Medicina, to the northeast, with 3,000 Neapolitan knights. The noose was closing around Manfredi’s forces, he had no choice but to fight his way out or retreat. He requested permission from the authorities in Bologna to go on the offensive, and had his request granted.

On December 5th, 1449, Astorre Manfredi’s forces left their fortified positions to attack Ricardina, northeast, where Gonzaga’s forces were bivouacked. On their approach, as they were setting their battle lines to attack Gonzaga’s men, two detachments of Manfredi’s troops, led by Scariotto and Gregorio d’Anghiari were ambushed by a detachment of Gonzaga’s army and routed. Manfredi was forced to retreat.74

When news of the defeat reached Bologna, Sante dispatched emissaries to Florence, led by Giovanni Bartolomeo Guidotti, to ask them if they could reason with Ludovico Gonzaga, who prior to this venture had been in the service of their Republic. On December 10th, Astorre Manfredi and a small detachment went to Gonzaga with a proposal for a truce, facilitated by the Florentines, and was successful.75 Diplomacy had won where military might faltered, now it was imperative for the prevailing councils to find a way to pry the vice-regent from the employ of the rebels in San Pietro. Galeazzo Marescotti and Dionisio da Castello, with a retinue of 25 men, immediately left for Rome.76

Pope Nicolas V was not in a conciliatory mood. His mind was firmly set on the reconciliation of the German Princes with their Hungarian counterparts. The Ottomans were on the ascent, and his bid to unite Christendom before their arrival was being met with constant derision—Bologna was a sideshow in the grand scheme of global affairs. When Galeazzo and Dionisio arrived, he agreed to demand the removal of Neapolitan forces from the contado on the condition that the Bolognese government accepted the Bishop of Perugia, Andrea Giovanni Baglioni, as governor of the city. This was agreed, and the pope sent for Campobasso, who upon conferring with the pontiff, retreated back to the Romagna, while Gonzaga withdrew his entire force back to Mantua.77

Peace was secured, but the negotiations with the Pope were still on-going. When Galeazzo and Dionisio returned with his holiness’ final demands, they were less than favorable. The ambassadors reported to the senate that Nicolas V demanded free rule of Bologna—obviously this wasn’t going to work—they replied back that they wanted to adhere to charters of 1447, and the pope responded to this by demanding the Governor and three representatives of the Bolognese leadership come before him to discuss the terms; they were Nicolò Sanuti, Gasparo dalla Renghiera, and Gasparo Malvezzi.78

After a prayer and a blessing, the ambassadors were given space to plea their case, Renghiera gave the oration, and explained the situation in grave detail, then asked the pope to observe the charters as they were agreed. Long tense silence followed. Then, their plight and the steps they had taken to secure peace were confirmed by the governor, Andrea Giovanni Baglioni, Bishop of the Archdiocese of Perugia.

Silence.

Then Nicolas nodded, and asked for some time to pray, and dwell upon the fate of Bologna.

After a number of suspenseful days of reflection and deliberation the Pope finally rendered a verdict. He would agree to adhere to the terms of the charters as long as the Bolognese people accepted Cardinal Bessarion as Papal legate in the city, and promised to abstain from violence. 79

When Bessarion arrived in Bologna, he issued an official decree that the rebel faction needed to vacate the solemn territories of the church, and scattered the remaining resistance to the wind.

The territory of Bologna was also troubled by the exiles and every day they made some news, always keeping the regiment under suspicion, so that the senate asked the legate to take care of them, so that the city would not live in such trouble; wherefore on the 13th of September, on Sunday, he had the following banished from the territory of Bologna: Romeo, Giacomo, Oppizzo, Antonio, Giovanni and Battista Pepoli, Giovanni, Antonio, Pietro and Jacomo Fantucci, Nani Viggiani and Francesco his brother, Alberto di Pietro Musotto and Nicolò his brother, commanding them that within eight days they should leave the territory of Bologna and pass over 60 miles under the penalty of confiscation of their goods and apply themselves to the Room ; they soon left and moved on to Imola, and in the meantime the senate regained the possessions of the countryside.

—Ghirardacci Book III, Pg. 136-137

The Carpi Conspiracy (Round 2)

Not ones to take the blessed word of the pope or his subjects with any kernel of sincerity, the Canetoli quickly started working on their next big coup. Factionally, the Bentivoglio were weak, and their list of enemies was growing long.

Of the remaining families in the Bentivoglesci faction, there were:

The Bentivoglio, Malvezzi, Bianchetti, Bianchi, Poeti, Marescotti, Guidotti, Bargellini, Caccialupi, Ingrati, Volti, Manfredi, Sanuti, and Caccinemici.80

In contrast, the list of families in exile, supporting the rebel faction, was massive and still growing:

The Canetoli, Ghislieri, Pepoli, Fantuzzi, Isolani, Linani, Ramponi, Viggiani, Correggie, Anticonti, Usbeti, Felicini, Albergati, Conti da Panigo, Musotti, Sala, Mezzovilliani, da Argile, Montini, Olivieri, Buonfigli, Cazzani, Campeggi, Ostesani, Meterlini, Mozzarelli, Gombrudi, Boccadiferri, Fusana, Dall’Abbaco, Caretti, Mussolini, Mastelacci, da Villonova, de Piazzani, Giovanetti, Panzarasi, Abrosini, Bambasi, da Cauno, Beroi, Henoch, Albertini, Vasselli, Zontini, Terzi, Cortellini, Piatesi, dalla Palmiera, Romanzi, dalle Fritte o Frutte, Monteceneri, Gustavilliani, de Copoli, Conti, dal Giogno, Garfagnini, Livrotti, dal Dottore, and Zazzarini.81

In the wake of the official banishment of the rebel families by Cardinal Bessarion, the Canetoli faction, led by our old friend Battista Canetoli, forged an alliance with the lord Carpi, Alberto Pio; the sovereign with the sick beard. The agreement afforded the exiles the money and troops they needed to raise an army and capture Bologna. When word of this alliance reached Bologna, the Anziani declared a state of emergency and rang the bells of the city to call the citizens to arms. Yet, no threat materialized on the horizon as they had anticipated, so they dismissed the militias, and turned a watchful eye to the west.82

Inevitably, it wouldn’t be a daunting barrage against the fortified walls of Bologna that brought the conspirators to bear upon the Bentivogleschi, instead it was a pair of low-born citizens—smugglers—scorned by the heightened suspicion of one of the twelve Gonfaloniere of the districts.

It so happened, that while Francesco Guidotto, Gonfaloniere of the district of Porta San Pietro, was doing his rounds on the night of 16 April, he happened upon two brothers, Cristoforo and Antonio di Biagio, carrying a sack of flour. He stopped them, and asked to see the contents of their sack. Unnerved by the encounter, the brothers threw the sack to the ground and fled to their home. Guidotto gave chase, and when he rounded onto the street where the brothers were living, found both culprits armed and waiting for him. A brief intense fight ensued, but the brothers di Biagio got the better of Guidotto and cut him down in the street.83

As Guidotto’s blood flowed into the canal, the Biagio brothers fled to Modena. They knew of a secret passage (smugglers port) into the city through the grate of the Reno canal, and used this esoteric route to escape. Now—safe in the company of the exiles— they shared the knowledge of this secret passageways existence with Alberto Pio, Battista Canetoli, and Romeo Pepoli.84

On the 7th of June 1451, 4,000 soldiers led by Alberto Pio, and the exiled cohort {making up around 3,000 of that number—for a full list see footnote85} set camp at Borgo Panigale, 5.1 km (3.1 miles) from the city.86 The twelve Gonfaloniere of the districts called their militias to arms and fortified the walls and gates of Bologna, while the core of the Bentivogleschi faction guarded the Piazza Maggiore.87 A detachment of the Carpesian-Exile army approached the city at the Arcoveggio pass, over the Reno River, near the Galleria gate that night. 60 of the men, led by Cristoforo and Antonio di Biagio, quietly slipped into the river, and swam to the grate. They emerged through the passageway into the city, and moved to the market just outside the purview of the Porta Galleria. There, they took ambush positions and waited for the militia patrol led by Dionisio di Castello. When their target came into view they attacked, shouting, “Church, Church, Flesh, Flesh!”88

Dionisio di Castello, frightened by the appearance of enemy soldiers in the city, tucked tail, and ran. Then, the forward team turned their ire on the gate militia, led by Dionisio di Castello’s son, Bartolomeo. They made quick work of the 30 man company and barred the doors of the gate’s fortifications so the Porta Galleria garrison, led by Gherardo dalle Giavarine and his three companies, couldn’t interfere with their business. They threw down the rastello (rake/iron latticed gate) and let Gasparo Canetoli, Francesco Ghisilieri, and Angelo Pio son of Alberto, into the city with 300 cavalry and 300 infantry. The exiles quickly started unloading bombards and crossbows, and staged their assault at the Church of San Gioseffo (later Santa Maria Maddalena).89

When the civic councilors of the Anziani and Sedici heard about this they fled, making their way to San Mamolo and Stra Castiglioni, where they made a pitiful show of themselves, as they hastily tried to escape by lowering themselves down from the walls with ropes.90 Sante, having been informed of the attack, and the regimento’s fearful flight, gathered together the leaders of the Bentivogleschi faction. Together, with Gasparo and Virgilio Malvezzi, Ercole and Ludovico Bentivoglio, and Giacomo dal Lino, they donned armor, and marched on the Piazza Maggiore, with a command of 400 well armed men.91

Sante, proved his cunning when he had the Bentivogleschi shout, “Sega, Sega, Astorre, Astorre!”, as the addition of Astorre to the traditional Bentivoglio war call of Sega, confused the exiles, and made them think that Astorre Manfredi’s mercenary company was in the city, when in fact he and his company were in Faenza celebrating Easter and Pentecost with their families.92 This sent the forward detachments of the exile forces reeling back to their staging point. Sante’s forces pressed on, and started to make contact with the enemy, Sante himself was singled out in the historical accounts for his valor, while Virgilio Malvezzi was mentioned for his exceptional courage as he cut through swaths of the fleeing rebels with his mighty sword.93

As more of the exiles turned and fled from the blades of the Bentivogleschi, the defenders picked up momentum, and drove them harder-and-harder like pitiful cattle, until finally they reached the gates of Porta Galleria. There, Angelo Pio, the son of Alberto, the lord of Carpi, was guarding the gate. Upon seeing his fleeing troops and the triumphant Bentivogleschi hot on their heels, he decided to take fate into his own hands—to inspire his men’s faltering courage with his own strength and valor, and charged at Sante Bentivoglio and Virgilio Malvezzi. Alas, a fated polearm arose from the crowd of fleeing men and hellbent Bentivogleschi, and caught Angelio mid-stride, flinging him from his saddle. He fell to the ground, unconscious, and was trampled beneath the feet of his frenzied cohort and the heels of their victorious pursuers.94

The exiles melted into the Emilian countryside, while the Carpesian host returned home to mourn the son of their aged and defeated lord.95 The next few years would be comparatively peaceful for Bologna. The now pervasive factional bloodshed wouldn’t heat up again until 1454, when another failed conspiracy engineered by Romeo Pepoli led to the extra-judicial execution of the plot’s chief conspirator Battista Mangiolo, a long time friend of the Condottiere—Iacopo Piccinino.

The ‘Peace’ of Lodi

Peace. A time for reconciliation, rebuilding, and if you’re an Italian Condottiere—retribution. For Iacopo Piccinino, there was only one apple worthy of his ire, and that was Bologna. His first solo-gig as a captain in his fathers mid-Italian proto-empire was acting as governor pro tempore for the city of towers at the age of 17.96 Once his term was up, he handed his oldest brother Francesco the reigns, and went back to Naples with his old-man Niccolò to battle the families vaunted rival Francesco Sforza97—that’s when the city was taken from them by Annibale Bentivoglio and his cronies, the Marrescotti.

After his father’s death, in 1444, he stuck around in the pay of the Milanese until Francesco Sforza assumed control of the dukedom in August of 1447; after the death of Fillipo Maria Visconti. In the wake of this set-back, he and his brother partnered up with Venice to forestall any advances of the blossoming Sforzesca dynasty in Lombardy.98 Then, after a brief stint holding his nose as a captain for Sforza in 1449, he went right back to Venice where he could continue his vendetta against his old rival, but after the peace of Lodi brought reconciliation between the Florentines, Venetians, Milanese, Bolognese, and the Holy See, he found himself unemployed, without any remaining family, and nowhere to turn but his own self-aggrandized ambitions—Bologna.

When Iacopo’s condotta with the Venetians was officially terminated, and his intentions became clear to the host of dejected Bolognese exiles strewn across northern Italy—intentions secretly conveyed yet again by Pope Nicholas V—they implored him to act on his impetus.99 26 April 1454, he did just that, gathering an army in Brescia, where he was joined by a host of diasporic Bolognese rebels and exiles who traveled to the region to join him. 100

The first order of business was to send official inquiries to the Pope, imploring him to bless their cause and to send the remaining troops and gold necessary to root the Bentivoglio from Bologna.101

Nicolas V, at this time was thoroughly annoyed with the Bentivogleschi faction; after their mistreatment of della Spada, and the disturbing reports from his Crusader Captain Pepoli, which resulted in his brief reconciliation with the Bentivogleschi in 1450, he saw his efforts toward an amicable peace inevitably devolve into evermore factional violence in the territory of Bologna—whether it was instigated by the Bentivoglio or not—the city and it's leaders seemed inept at following his orders.

That said, the real kicker came in 1452 when the Pope started to meddle in the conflict between Venice and Milan on behalf of the Venetians, which eventually ended with the aforementioned Peace of Lodi. Bologna had no choice but to defy his holiness when he asked for their support, and ended up remaining neutral, on behalf of her allies Florence and Milan.102 Remember this; “Should the lords of Anziani and the Sedici wish to send any embassy to the pontiff or the lordship of Venice or the Florentine lords, they may do so as much as seems appropriate and necessary to them, and this should be done by common counsel”?

Unfortunately for Sante and the Bolognese, this section of the charter didn’t say anything about Milan, who at the time of their writing were under the rule of the Visconti and posed a threat to Bolognese sovereignty, but Sante’s great mentor in the prevailing years between the ratification of the charters and the war, was Francesco Sforza, the new Duke of Milan, a relationship fostered by Galeazzo Marescotti and Cosimo di Medici.103 In due course he swore to uphold a mutual defense treaty that was signed between the three northern Italian powers; Florence, Milan, and Bologna—as both Francesco and Sante owed their respective roles to Cosimo di Medici. It was a deal that provided legitimacy to the Bentivogleschi rule in Bologna, and all but guaranteed her liberty, but Papa Nicholas didn’t care, in his mind he had already afforded them that grant of indemnity. Thus, this was a bridge to far for his holiness to abide—a betrayal, and as such, he decided it was best to unburden his Beatitudes of the Bentivoglio once and for all.

War Games

When word that Francesco Piccinino’s army had started to mobilize reached Bologna on 26 April 1454, Sante sent emissaries to Florence (Ludovico Caccialupi), Milan (Nicolo Poeta), and Venice (Virgilio Malvezzi) asking them what he should do. The young Signoria was busy, he was planning his wedding to his child bride, Ginerva Sforza, niece of Francesco Sforza. His allies simply told him not to worry, that Iacopo was penniless and hapless—so, Sante listened.104 News followed with the official ratification of the Peace of Lodi by the King of Naples, that September, which was cause for further celebration—affairs in Bologna seemed to be settling after years of tumult.

Then, on the 6th of February 1455 the Reno Valley was rocked by a massive earthquake, and in the wake of this disaster, on the 14th of February, Iacopo Piccinino’s army swarmed into the Emilia region, crossing the Po on its way toward Bologna.105 Bologna’s allies, and her scouts had vastly underestimated the purchasing power of Iacopo Piccinino, his 4,000 strong contingent {3,000 cavalry and 1,000 infantry} stipend by the Pope and the exiles proved an insurmountable task for the reeling Bolognese.106 On account of the plague and the devastation wrought by the factional infighting in the city, Sante was unable to muster a sizable army to contend with Iacopo, he would have to rely on the good will of his allies, there would be no fated battle at San Giorgio, like his predecessor Annibale; Bologna was helpless.

Ludovico Caccialupi thundered out of the Galleria Gate toward Lombardy the moment the news of Piccinino’s army arrived. He dismounted in Milan on the 19th, and immediately went into a private council with Francesco Sforza. Caccialupi made it clear to the duke that Iacopo was not acting alone in this endeavor, that intel indicated that the Pope, Nicholas V, had facilitated the Condottiere’s actions, and had designs on not just conquering Bologna but the fiefdoms held by the duke in the Romagna and the Marche—like his homeland Cotignola.107

Francesco called his captains together, and dispatched an army of 4,500 men (4,000 cavalry; 500 infantry) led by his most trusted lieutenant Roberto da San Severino. Sforza, was a man who had known war his entire life, and he understood that men who were fighting for something they loved—for their homeland—fought harder than those who had nothing to lose, so his junior captains accompanying Roberto were all Romagnol and Emilian descendants; namely, Corrado da Cortignola, Evangelista Savelli, Cristoforo Torello, Giacomo de Russi da Parma, Saramoro da Parma, and Amerigo da San Severino among others.108

The army departed Milan on the 19th of March, and arrived in Bologna a few days later. Roberto stayed in the city, while his army camped just outside. Once they were settled, he dispatched Sir Corrado da Cortignola with 1,000 cavalry to reconnoiter Iacopo Piccinino’s location, and get a clearer picture of his intentions.109

Meanwhile, the Anziani and Sedici decided they needed to send an ambassador to the Pope to seek a diplomatic resolution before things got too complicated. After a few days of deliberation they concluded that the only man who could sway his holiness into acting with reason and justice was—Ludovico Bentivoglio. He set out immediately with a retinue of ten men and the weight of the fate of his beloved city on his shoulders.110

Pope Nicholas (Round 2):

After Ludovico had rendered the proper platitudes to his holiness, and prostrated himself accordingly, the Pope welcomed Ludovico Bentivoglio like an old friend. Nicolas had him approach the dais of his throne, and bade him to sit beside him. There, they reminisced about simpler times when the Pope was still a young man attending university in Bologna. Ludovico had inspired him with his virtuous works, paternal kindness, and love for the city he once called home.111

Nicolas paused, touched Ludovico’s shoulder and said, “Tell me, O Ludovico, where does it come from that my dear citizens of Bologna don't want me, since I love them as blessed children?"112

Ludovico nodded and looked Nicolas in the eye, as he said, “Alas, holy Father, what do I hear from the lips of your Beatitude? In truth the regiment and the whole city love him as their most merciful father and benign lord, as I do myself, even risking offending God’s grace as I tell his holiness the truth. Please, Most Holy Father, may it be permissible for me to say this to you: what does your Holiness have to complain about in Bologna? Perhaps that it is not governed with honor and does not laud the Apostolic Chair?”113

Ludovico’ expression became stern, “Of course it does. If your Beatitude is being told of ‘the evils of the Bolognese regiment’ and is given to the notion that it would be an eternal honor for his Holiness to freely have Bologna offered to him like it was some good to be purchased—then, as you know, anyone who believes this is deceived, and these are vain thoughts that are being fed to your Holiness, because these notions do not come from the love they bear for you, but from envy that afflicts them inside their hearts, of their desire to be greater than others or because they always like to see "new" things and crave changes of State.”114

“In truth, these people, who wish to annul the freedom of our state for any of these two parts, cannot truly be called excellent citizens and I leave all this to the discretion of your Holiness to judge.” Ludovico continued, “Allow me to be clear, having Bologna in the hands of those whom with such ardent desire have offered it to your Holiness, who it is to be believed will not achieve an execution of such measures without wanting to be made great in the city or without being endowed with great gifts. I will say that their desire is insatiable, it would happen to him as to the one who warms the snake in his bosom, when the frozen winds blow: he is the first bitten by the snake, and I feel that his Holiness would then see these people so sublimated near his Beatitude, one day wanting to be near of her greatness, and then the next—they would usurp the dominion of the city for themselves with little honor for her and for the Holy Church."115

Shaking his head, Ludovico said in a quiet voice, “And for this reason I am not a little surprised that these things are not thought of, since the Bentivoglio state is governed together faithfully with your most revered legate {Baldasare Cossa}, with the honored title of Holy Church. Who does not want to approach these unjust resolutions? I humbly and devoutly beseech your Clemency to disparage these thoughts, and become aware that every thought and intention of theirs which is harmful to our state pleases them in part, as a salutary conversion. Invest us with your foremost grace as your children and most faithful servants of the Holy Church, to which, and to you, it will be unto God and the world more honor and praise. As in our beloved city of Bologna, to make any change, were it so, it would not be without great bloodshed and incomparable damage to all the people. Then in short, fatal dissent in Bologna would make for itself a new movement with little honor for our most Holy Church, to which it will then reign in infamy; and I say this to my great sorrow—she has long been faithful to the Holy Church—yet it seems every year that the state of Bologna is taken away from her.”116

In a bold voice he proclaimed, “But now, by divine virtue and by the valor of my magnificent regiment, it is not so, because the regiment is a tender lover of the Holy Church and is a most loyal son to her, and desires to suffer every trouble and danger to preserve her state. For which reason, Most Clement Holy Father and our Lord, my regiment has confidently elected me ambassador—although unworthy—and sent me to beg at your feet not to impede our state. A state which now seems to be in danger on the account of some perceived past injustices purported by Count Iacopo Piccinino, who has done great damage to our territory, and seeks to extort some 40,000 ducats for the damages he claims his brother received in Bologna—which in the past we know that the count wouldn’t have done on his own volition, nor would he dare to molest the lands of the Holy Church; that is, not without your understanding and without the persuasion of some of our citizen enemies.”117

Lodovico fell silent, then looked up, and said, “To which danger do you bow your benign head? As a faithful shepherd of Christians, to obviate, for the common good and peace of a maligned Italy, one where the said count is forced to pass without any harm to us on his journey, deserving unto God, if ever HE were gracious towards anyone, give us help in words and money, so that the count, wanting to offend us without your blessing, will afford us the chance to defend ourselves better, and therefore as your dear children, prostrate on the ground, we humbly and dearly ask you, free us from the ailments and dangers that arise from this affront.”118

The Pope was enamored with Ludovico’s impassioned speech, but he took a moment to dwell on his words before forming a response and somewhere in his contemplation his expression changed as he looked up, and said, “My beloved son, if your regime is so eager, as you say, to suffer every worry and toil for the sake of the state, of the Church, why do they not wish to give me Bologna, a city whose inhabitants are so loved by me, because of the great virtues I acquired there? If your regiment were to do this, we would insure it from every danger and all of you would live in perpetual tranquility as blessed children of the Apostolic chair, to whom I will always be dearest, Most Holy Father?”119

Ludovico smiled. “This couldn’t happen until the greater security of our citizens is guaranteed, for fear of being offended by their enemies thirsting for their blood and also for the number of corrupt rectors of the Holy Church who have governed in Bologna. As His Beatitude can well recall, the great damage the whole city experienced not once but several times, being in a lesser degree in Bologna at the time when the cardinal of Spain {Daniele Bishop of Concordia}, our legate, whose ambitions were not in an ecclesiastical way, but in those of the devil, who went about with armed guards, and clashed with the noble citizens, who they attacked and insulted out of contempt, in addition to the many rapes, violence, and murders committed in the city—when we were forced to live with those disgusting customs. Which was also something worthy of great compassion, considering that Bologna can be counted among other excellent cities of Italy.”120

Ludovico’s expression saddened as he said. “What can I say, most clement Father, of the vituperative death which befell Antonio Galeazzo Bentivoglio, the flower of our illustrious Italy, whose virtues—the more one wants to talk about them, the more they can’t stop talking about them? Please be content then with the excellent government of our regiment, and allow, as I humbly beseech you, to set aside the advice of those who are more eager for the ruin and deaths of the virtuous, than they are enemies of iniquity. Holy Father, here I am supplicant at your holy feet; grant us the grace that I ask of you and do not allow the hope of my citizens to be in vain, as upon my departure from Bologna I guaranteed them that all my pity and kindness would be at their disposal.” 121

Nicolas, who had been attentive to Lodovico's words, was already moved. As a tear rolled down his cheek, he said, “Know, O Lodovico, that through your words I recognize the wickedness of those evil men; this is enough for now; go to your room and be happy that you will leave me consoled, and on Thursday I'll wait for you to have dinner with us.”122

Lodovico stood, and departed with the upmost modesty and reverence. When Thursday came, he returned to the palace where he found pope Nicholas admiring some opulent buildings that he had recently commissioned. Unfortunately, as he waited to be attended by his Holiness, the Pope’s gout flared up and left him in a crippled, bedridden state. The pontiff’s handlers informed Ludovico that they weren’t able to continue their discussions today, that they would call for him when the pope’s condition improved. That evening, while Nicholas was convalescing, his Holiness had the bishop of Perugia, Pietro di Nosetto dine with Ludovico in his stead.123

Fifteen days went by with no word from the Pope or his officials. As the days turned into weeks, Ludovico was greeted with little more than the constant stack of incessant letters arriving from Bologna begging him for updates. He had nothing to offer them—until one day while he waited outside of the Popes chambers—it struck him. After weeks of pleading with the clerics, scribes and bishops circling the popes bed like a committee of famished vultures, he happened to spot his Beatitudes doctors leaving his chambers, two gentlemen by the name of Bernardo de’ Garzoni and Baviera de’ Bonetti; he would never get a word through the corrupt bureaucratic blowhards fighting for scraps at his Holiness’ table, but he might be able to get close to his doctors.124

Ludovico set out to make friends with the Popes physicians, first he introduced himself—asked them if they needed a hand. Then he would greet them daily—walk with them, invite them to dinner; placate—schmooze them, until finally he asked them for a simple request, to beseech his holiness for an audience on his behalf.125

The next day when Bernardo and Baviera were finished bleeding his Beatitudes, they acquiesced to Ludovico’s request. Nicholas was amused and responded, “Who better than you to bear witness of the illness that afflicts me, and prevents me from giving Ludovico an audience as I’d like, tell him that I remember him and we will not give an audience to any cardinal or embassy before him, no matter their self-aggrandized position or esteem.”126

When Nicolas’ condition improved, he followed through on that promise. Ludovico was the first to be called to his bedside before all of the cantankerous Cardinals and highfalutin philanderers trying to beat down the popes door. When Ludovico entered his Beatitudes bedchamber, he graciously wished his Holiness well, and knelt beside his sickbed. After a brief recantation of his key talking-points from their last conversation, he begged the pope to to preserve Bologna from the evils that threatened her liberty. To which Nicolas responded, “Ludovico, we are happy to do whatever you ask for your regiment in Bologna.”127

Ludovico felt his heart skip a beat. Tears started to roll down his cheeks as Nicolas continued in a strained tepid voice, “But before we move on to something else, to show the people of Bologna how much your virtue and value have become known to us, and the esteem for which I hold you, we want to adorn you, by our blessed hands—giving you and your children a most sacred gift, by making you a knight of the Golden Order.”128

Ludovico started to weep and laid prostrate before Nicholas as he said, “I thank God, oh Holy Father, who until now has enlightened me to preserve myself, that I may be spared the honor by other pontiffs, emperors, marquises, and notable lords, because he wanted to reserve this honor for your Beatitudes. I willingly accept this honor from his great kindness, even though I am unworthy, and let it be known that I am happy to serve his paternal will.”129

Nicholas nodded, and asked his aids to fetch Bishop Pietro da Nosetto and his secretaries. When they arrived he said to them, “Bring our sword here without any delay.” There was a pause—his servants were clearly confused, “You ignorant fools, tell me, is there not our sword that we keep above the altar on Christmas night, when we celebrate Holy Mass?”130

“Yes Holy Father”, the bishop replied.

“Good, now bring it to me.”

One of the secretaries stepped forward, and piqued, “Holy Father, we didn’t believe you meant that one, because it was intended for the Duke of Burgundy {Charles the Bold}, the nephew of his Majesty the King of France, and other worthy princes have asked you for it in the past and you’ve denied them.”

Nicholas started wagging his finger, “Although these people you’ve mentioned are worthy of a similar gift, they were not, however, worthy of this one like our dear Ludovico Bentivoglio is, who due to his singular prudence and great virtue is worthy of every supreme honor and reward, as his virtue has hereunto exceeded that of every man of noble blood and vast estate.”131

The aids left the room at once to fetch the vestments. When they returned, Bishop Pietro da Nosetto, a count and a knight, started the ceremony by placing spurs of fine gold upon Ludovico’s feet, then the Pope gave him the Holy Sword and Hat, and created him, his sons, and the sons of his sons Counts of the Lateran Palace, and said, “Pray Knight, to God who grants us health, that as much as we have done, it is never our will to do so, because our intention here is to do something towards you that will bestow honor and glory not just to you, but to the whole of the Bentivoglio family, and their status in Italy.”132

Victory!

Ludovico had secured the Pope’s support against Iacopo Piccinino and the exiles, to which his Holiness added a large sum of money so the Bolognese government could hire troops to defend their lands, a holy sword and hat, and a noble title. When Ludovico emerged from the Popes rooms and walked out into the streets of Rome, to his surprise, they were alight with celebration. He didn’t stay long to take part in the revalries, and instead departed for Bologna as soon as he could, arriving home on March 9th, a Sunday. The Saragozza gate, the triumphal gate of the city, used by kings and Popes, was teeming with excited citizens, jostling to get a look at the Holy Sword, and the native champion that left the city as a common man, and returned as a christened knight, count, and wielder of a sacred vestment.133

Ludovico rode through the gate holding the bare blade of the holy sword aloft in the air. The crowd pressed in and chanted, “Sega, Sega, Sega!”. Cardinal Bessarion was waiting for him on a beautifully crafted dias, with all of the knights, doctors, and nobles of the city.134