The helmet atop young Hugo Pepoli’s head was pitted and scarred. It had been struck, scored and marked hundreds of times from strong blows of the foil or fencing sword. It fit him awkwardly and bounced as he went to take his place in the piazza. Despite himself the boy felt sick in the stomach and weak in the knees. He was afraid, but not of his opponent -- that little runt Guido Rangoni did not frighten Hugo at all. What Hugo feared was embarassment, humiliation. Shame.

Outside the brick façade of the great Palazzo of the Bentivoglio stood Hugo’s father and mother as well as Giovanni Bentivoglio, the lord of Bologna. They were surrounded by courtiers, hangers-on, honored guests as well as an army of servants. All were braving the blustery cold of a December day to watch him cross swords with his cousin Guido. Papa Pepoli had made the error of boasting of Hugo’s skills in the saddle and with the sword and now Uncle Giovanni wanted to see how he compared to the Bentivoglio’s own future general, little Guido Rangoni.

Hugo took a few swings again at the air with the foil – a quadrangular sword simulator tipped with a leather ball. It lacked an edge though the corners of the sword could lacerate the skin. He banged it softly against his buckler to get a feel for their weight together. Then he turned to address his opponent.

Guido’s fencing master was serving as the master of the fight. In a clipped Tuscan accent he declared, “Salute.”

Hugo drew himself up to his full height with his back straight – as he had been trained to do so many times before. He turned his foot towards Uncle Giovanni, placed his buckler over his ribs and let the point of his sword fall down and to the right. He inclined his head slightly as a signal of honor.

The master declared, “Fight.”

As he had practiced so many times before, Hugo took a big step forward and struck the face of his buckler with his fencing sword, a blow that turned the face of his little shield towards him, like he were looking into a small metal mirror. Then he banged the pommel of his sword into the buckler and stepped forward again raising the sword so that it covered his head. He now threw a number of other flashy, eye-pleasing cuts and made other swashing actions into his buckler as he drew closer to fighting distance. Young Guido made similar beating actions into his own buckler and the sound of their bucklers mingled and made for a rhythmic tattoo that echoed and reverberated in the confines of the small piazza.

The sound pleased the audience, both with its music and with the expectancy that it brought to the moment of their clash.

In keeping with the style of the time both young fencers came to fighting distance, or at least fighting distance for the taller Hugo Pepoli. They both stood with their swords high and their bucklers extended at full arms before them. In this position they had all the grace of dancers and yet stared at one another with the savagery of angry tigers.

Young Hugo was the first to strike. He took a long gliding step forward, his foot moving in a straight line so close to the paving stones of the piazza it could have knocked over a coin lying on the bricks. As he stepped he threw a descending right blow with his sword towards Guido’s face, letting his hand move behind the cover of the buckler to keep Guido from striking it.

Ever aggressive, Young Guido threw up his buckler to block the strike to his head while simultaneously stepping forward and throwing a strong blow at Hugo’s legs.

Hugo was prepared, he had in fact trained for this exact action many times. Before his sword even touched Guido’s buckler, he pulled in toward his body and brought the sword towards his body and then over his elbow. At the same time he brought back his front foot and pulled it beside his left foot, so that Guido’s blow to his legs passed by harmlessly.

Then as Guido’s sword was still moving towards Hugo’s right side, young Hugo stepped straight at Guido with a reverse cut to Guido’s face. Rather than pull this blow from left to right, Hugo pushed the blow forward almost as if he were making a thrust.

At the same time Guido had followed his own right cut to the legs with a strong reverse blow to the head of Hugo Pepoli, but the angle of Hugo’s pushed roverso set aside Guido’s strong blow while putting the point of Hugo’s sword in Guido’s face.

To keep himself safe Guido put the buckler between Hugo’s sword and his own face, momentarily blinding himself while at the same he threw a horizontal right blow at Hugo’s head, trying to cut under his buckler.

With perfect timing young Hugo Pepoli made a thrust under his buckler while making a powerful turn of his body, joining his two hands together as he sent the leather ball at the tip of his foil into Guido’s face and binding their swords together. Feeling the danger of the thrust Guido shoved Hugo’s sword away, still covering his hand with his little buckler. This exposed the left side of Guido’s head.

Now Hugo uncorked two of the spinning cuts called ‘tramazzoni.’ These were rapid, circular cuts that spun in place like the wheel of a windmill. The tramazzoni flew so fast that the eyes of the audience could could barely discern the movement. Through some instinct, Guido managed to escape these blows, leaning away and throwing up his buckler. The second one of these made a scratching noise as it scraped alongside the rim of Guido’s buckler.

Once the second blow no longer presented any threat, Guido lurched forward with a strong vertical cut to Hugo’s head.

But Hugo knew what was coming and was already moving to intercept this blow. He brought his sword and buckler together into a defense they called the Guard of the Head, lifting his sword so that it caught Guido’s blow near the cross of Hugo’s sword. Hugo now had mechanical leverage over Guido’s sword, since the the tip was the mechanically weak part of Guido’s blade and it lay against the base or strong part of Hugo’s sword.

Now Hugo turned his sword to trap Guido’s sword against his own and then rotated his body to make a strong right cut at Guido’s leg. With remarkable dexterity Guido withdrew his leg away while extricating his blade away from Hugo’s sword. Hugo reached forward to try and cover the distance to Guido’s leg but he was too slow.

In reaching forward to get Guido’s leg, Hugo had let his head stray forward and down so that it was exposed. At the same time Hugo’s cut now moved under his arm so that the point was directed completely away from Guido. The way was now open to strike Hugo’s head and Guido spun a reverse blow from his elbow towards the right side of Hugo’s head.

But Hugo knew it was coming. Before Guido’s sword was even en route, he drew his head back away from Guido, so that his body moved into a standing upright position while at the same time he brought a strong reverse cut from an underarm position. Hugo’s blow landed over the top of Guido’s sword, sending it downward. Guido’s momentum had brought him forward for the attack. But now Hugo’s sword was between Guido’s face and Guido’s own sword. Guido now lurched backward to avoid Hugo’s attack, bringing his buckler in front of his face to protect his eyes.

Hugo was not seeking to attack Guido’s eyes. He was going to hit Guido where it really hurt – in the pride. He brought the tip of his sword around Guido’s buckler, in front of his face, and then up to the brim of Guido’s helmet. With a slight flourish Hugo brought the tip of his sword on the back edge side of the slide along Guido’s face and then upwards until he flicked the helmet off of Guido’s head and sent it falling to the ground. It landed against the paving stones with a resounding clang as if it were a drum.

Growing red-faced with shame and anger Guido hurled himself at Hugo, desperate to avenge this insult. But Hugo was now stepping backwards with a powerful downward cut into his buckler that knocked down Guido’s sword and then Hugo swashed his buckler and put it into Guido’s face.

Then the master was there and put his staff between the two fighters.

“Point, Pepoli,” the master declared.[1] Then he looked at young Guido, shook his head and made disapproving clicking sounds, disappointed with Guido’s performance.

Hugo Pepoli walked back to his side. The sour feeling in his stomach and the weakness in his knees were gone now, he couldn’t wait for another chance to whack ‘the runt’…[2]

In the late 1400s, the city of Bologna, in Northern Italy was enjoying a period of peace and prosperity long unheard of in its bloody history. The moderate rule of the Bentivoglio family over Bologna governed with a firm enough hand to keep the peace without being so tyranical as to incite people to violence—a most delicate tightrope act in Renaissance Italy.[3] These Bentivoglio were popular enough that the ruler of the city could go about its streets with only the smallest guard or sometimes alone, in disguise.[4]

In the summer of 1485 the Lord of Bologna had even more cause to celebrate: his first two grandsons were born. The younger of these two boys was named Guido Rangoni, the fruit of Grandpa Bentivoglio’s eldest daughter and the leader of his army. Though born with the surname Rangoni, the first quarter of Guido’s life would revolve around the fortunes and vissicitudes of the Bentivoglio family.

In that same year the Pepoli family of Bologna also welcomed a new edition to the family, a baby boy named Hugo Pepoli.[5]

The boys were doubly second cousins, sharing two great-grandfathers. Since they were the two most promising warriors of their generation in Bologna, they would have been rivals even if their families were not the first- and second-most powerful in Bologna. The Bentivoglio (the more powerful of the two families) and the Pepoli had a complicated relationship. Grandpa Pepoli had tried to kill Guido’s Great Uncle. In return, Guido’s great uncle had had Grandpa Pepoli murdered.[6]

When Guido and Hugo were kids that all seemed like so much water under the bridge.

Between Granpda Bentivoglio and Hugo’s father all seemed to be well. Papa Pepoli accompanied the Lord of Bologna on pilgrimages, escorted his children to destinations outside of the city, and acted as a general representative of Grandpa Bentivoglio.[7] He was less a warrior and more a gentlemen of good manners and intelligence beloved by all.[8]

Grandpa and Grandma Bentivoglio had eleven surviving children, but only four sons to protect and promote the family fortunes. In a world where violence was the ultimate arbiter of justice they essentially acquired more sons by marrying off two of their daughters to some of the leading mercenary captains or condottieri and then giving those condottieri jobs and lands around Bologna, essentially tying them into the family fortune. This is how Guido’s father came to live, work and keep his family in Bologna. When Bologna made Guido’s father the Captain General of all Bolognese forces, Grandpa Bentivoglio offered him his eldest daughter in marriage.[9] It was a good match. Bianca Bentivoglio Rangoni was a woman of considerable wisdom and force who—as we will eventually see—was instrumental in improving the fortunes of her many children.

As Papa Rangoni’s eldest son, it naturally fell to Guido Rangoni to become the military leader of his family. The first thing that a future warrior like he or Hugo Pepoli had to learn was the art of horsemanship. For a knight a horse was more than just a way to get around, a well-trained horse was also a weapon. The ability to handle the horse was the first mark of the noble warrior. The boys had to learn to sit with their bodies, “inclined just right, corresponding and harmonizing [with their horse’s movements] no less than if it were music.”[10]

Along with proper posture and balance throughout their bodies,[11] they also had to learn how to handle their horses without fear, with the goal of all their training being that, “The horse should perceive you as part of itself, sharing the same body, sense, and will.”[12] A mounted warrior need to do more than just ride straight at the enemy. He needed to lead his horse over all sorts of broken terrain that challenged the balance of the horse. He needed to stay perfectly balanced as his mount wheeled first this way and then that way. Finally he needed to lead it into battle and the training with the horses involved extensive repetition of simulating battle of charging, “toward the enemies with the lance, and then, drawing out the sword, to enter and exit from the charges in the midst of them.”[13]

Here was one place for the rivalry between Guido and Hugo to play out when they were kids. The emphasis on riding with good form, with perfect balance and the ability to sit a horse perfectly would have been one easy source of comparison.

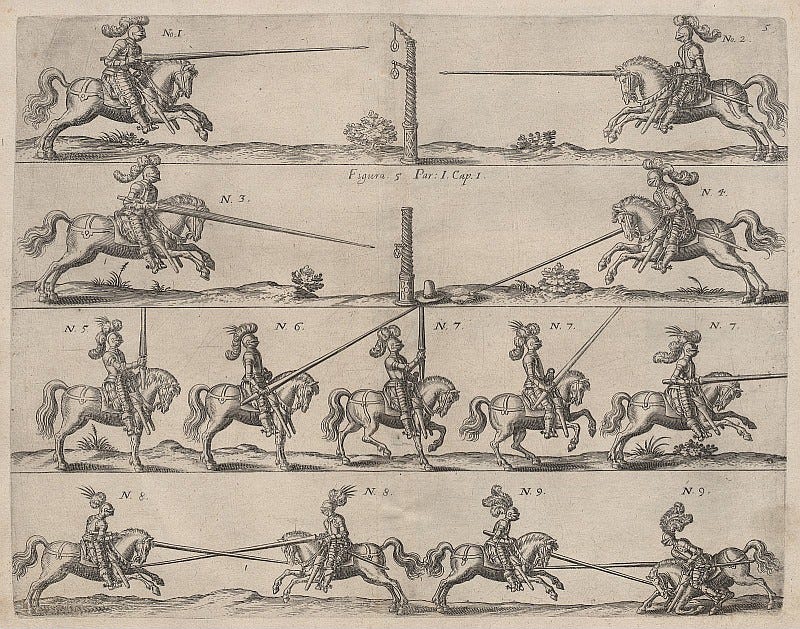

Once the boys could arrange themselves straight upon their horse, carrying their weight mostly in the stirrups and not in the saddle, while staying balanced and being able to carefully vary the pressure against the girth of their mount with their spurs, then they were ready to learn to tilt.[14]

Tilting, the use of the lance for a joust, was both a sport and preparation for war. The lance was the signature weapon of the knight and the charge of a group of armored cavalry still considered the most important part of any battle. The boys needed to learn to use the lance as they would do in a joust. In this period the base of the lance was usually retained in a pouch – a piece of metal or leather attached to the saddle or armor.[15] From there the common practice was to lift the lance and place it up against the lance rest on the outside of their cuirass. This would allow them to keep the lance secure against their body while also keeping the muscles of their arm relaxed—a practice that improved control of over the point.[16] This more effectively allowed the tilter to channel the full power of their charging horse into the tip of the weapon.[17] Alternatively the young knights-to-be needed to be able to couch the lance under their arm.

To master the lance the boys would use light lances on foot, charging at a quintain or at some kind of wooden man.[18] Once that was complete they would practice on horseback, leading their horses to charge forward at a slight angle towards the quintain, trying to strike a tiny target from the back of a charging horse.

Here too was another area of rivalry, and we can easily imagine Papa Pepoli and Grandpa Bentivoglio pitting them against one another. This would have been not just for parental bragging rights, but to help hone the boys for the future they would face, since few things spur greatness like vigorous competition. Here they would have developed their own style for jousting. The biggest individual difference in jousting technique was whether to immediately emplace the lance against the its rest on the cuirass and then charge, or to lower it so that it came down into place right before it struck the enemy. The advantage of the latter technique is that gave no time for the lance to bob left or right, but the downside was that it represented a tough piece of timing.

The famous master of arms Pietro Monte had strong words against this technique. “Those who believe that they can predetermine in the beginning how far to carry the spear across or straight are generally mistaken. We should constantly direct our spear [lance] at our opponent.”[19] But as we will soon see, for little Guido Rangoni, there were serious real-world advantages to learning to attack with a spear not pointed at the enemy.

The final place for the rivalry between the two young cousins to play out was in the fencing hall. No one recorded the friendly bouts of boys, but the martial practice of Bologna emphasized acquiring experience by “practicing with a variety of partners.”[20] The key to fencing in the Bolognese style, or in any style, was the mastery of timing, of recognizing the opportunities to strike, or better yet, stealing opportunities to strike.[21] For this exercise the boys learned to fence with the spada da gioco a kind of light practice sword used in one hand, probably featuring a quadrangular blade with sharp corners,[22] and mostly likely tipped with a ball of some sort.

The term “fencing hall” brings to mind a large and spacious room, purpose-built for fencing. These fencing halls were likely anything but spacious.[23] Teaching was a big part of the business in Bologna, home of the first University in Europe.[24] Rather than having a campus, in that time teaching was often done in the houses of the professor, and fencing schools probably worked on the same basis. Thus the “fencing halls” were probably nothing more than an extra spaces in the house of the maestro. In 1497 Guido Rangoni’s uncle Hannibal bucked the trend and built a grand new palazzo near the family’s palace, a building he dedicated to the practice of arms. He called this building the casino. Here Guido' must have learned some of the art of fencing from the master at arms Maestro di Luca.1

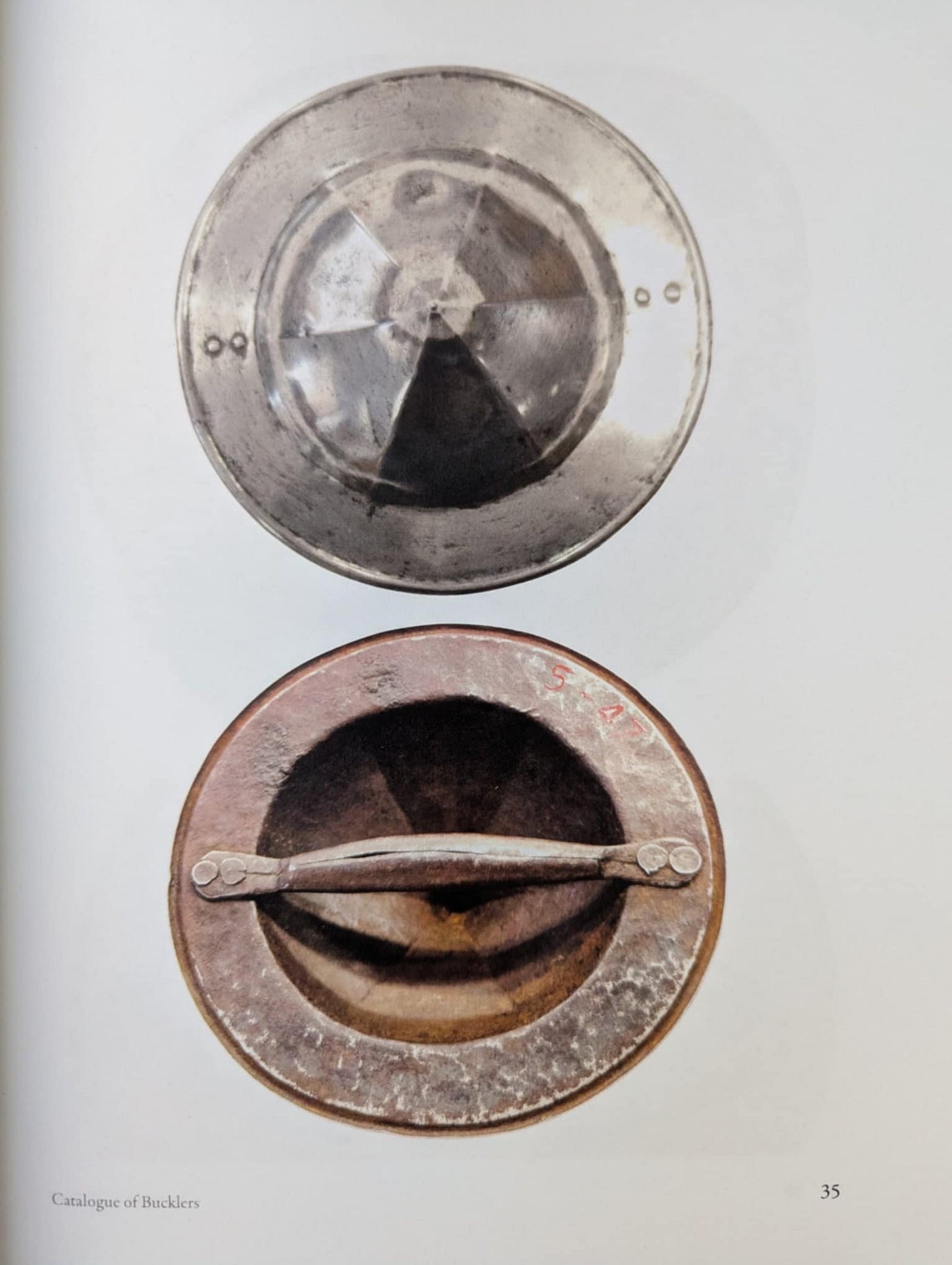

The practice of fencing was done with the practice sword and the small buckler, a diminutive shield used for fencing.[25] These bucklers could be as small as 175mm or seven inches in diameter. They were the preferred arms for teaching the art of the sword, since the little buckler kept a fencer’s hands safe but still forced them to use the sword to defend themselves. For decades at least the city of Bologna had paid professional fencing masters to help its youth learn to fight.[27] As befit a University city like Bologna, the putative founder of the local method of fencing was a Professsor of Astrology and Geometry named Filippo Dardi, who was put on the city payroll as payback for helping put the Bentivoglio in power.[28] This fencing master and other Bolognese masters developed a sport of fencing for their students based on the sword and buckler.[29] This sport was not just for fun and not just to keep idle youth busy but also, “for the utility of the young men of this city, and for the honor of the state.”[30]

In this Bolognese game, strikes to different parts of the body offered varying amounts of points, but the head was the most valuable target.[31] For a taller fencer like Hugo Pepoli, powerful downward strikes to the opponent’s head were a natural attack. Hugo Pepoli’s maestro would have told him to keep his blade free and in constant motion, the style of fighting the Bolognese called, “wide play.” For a shorter fencer like Guido Rangoni the game was trickier. Being shorter meant he lacked reach in comparison to Hugo Pepoli. Rangoni’s teacher Maestro di Luca would have taught Guido to cross his weapon with his opponent's weapon and control it so that he could enter into striking distance. The masters called this “close play.”[32]

Getting close was dangerous for both of them. This “friendly” fencing without sharp swords also involved punching an opponent in the shin or face with the buckler; it also featured kicks to the groin, as well as throwing an opponent bodily to the ground.[33] There were no weight classes, so a bigger and stronger fencer also held a distinct advantage in these wrestling actions.

Thus Hugo Pepoli probably got the better of Guido Rangoni in these youthful matches. Guido Rangoni got the better education, though. He learned how to fight at a disadvantage, a lesson that would serve him well in the real world after the boys became men. He particularly learned that by carefully controlling the distance between the two of them, and by aggressively pursuing the proper times to strike, he could at times overcome Pepoli’s physical advantages. This kind of education would serve him well on the battlefield.

Here then was the real purpose of all the sword practice, to teach the boys to be clever and savage and above all to control their fear. As the Renaissance fencing master Francesco Altoni noted, a fencer only needed to, “practice to see the harm that fear does them, and so in this way a person can learn to regulate themselves bit by bit.”[34]

Opportunities for the two young men to cross swords became fewer as the years passed. Hugo Pepoli’s father grew increasingly distrustful of Grandpa Bentivoglio and as Hugo grew older his father sent his sons away from Bologna.[35]

Guido Rangoni seems to have remained in Bologna, learning his craft there, and learning from his father his core creed: man makes his own luck.[36]

This debate; was a man’s success driven by fortune or by his own virtue, was a frequent argument. Guido’s father was a passionate believer in the the power of virtue over fortune. One hot summer day Guido’s father even got into a passionate argument on this very topic with Guido’s uncle Hannibal Bentivoglio.[37] Hannibal claimed that fortune held greater sway over a man’s destiny than action. To settle the matter Grandpa Bentivoglio held a great joust in Bologna where the forces of Fortune did battle with the forces of Virtue.

Alas, Team Virtue lost on that day to the power (and luck) of Team Fortune.

This would prove the last of the great tournaments in Bologna, at least for a few generations. In 1495, when Guido Rangoni was ten years old, the great gathering storm finally broke over Italy. In one of history’s bigger unforced errors, the Duke of Milan[38] invited a French army into Italy to solve some disputes the Duke was having with the King of Naples in Southern Italy. The French army swept through Italy like a veritable blitzkrieg, with “no more trouble than to mark their lodgings with chalk,” as then Pope Alexander VI described it.[39] Grandpa Bentivoglio was forced to give the French passage, and it fell upon Guido’s father to shadow the French army and keep them from causing too much mayhem in the Bolognese countryside.

After the French made short work of the army of the King of Naples, the other Italian powers, particularly Venice and Milan, everyone quickly recognized the danger of the French presence in Italy. They hastily assembled an army that included thousands of Bolognese infantry as well as a battalion of armored cavalry under the command of Guido’s uncle Hannibal. This army under the leadership of the Marquis of Mantua beat the French at the Battle of Fornovo and drove the French out of Italy and back over the Alps.[40]

Still the French invasion had disrupted the careful balance that had maintained peace in Italy and the next three or four years were consumed with constant war—a contest largely played out between former allies Milan and Venice.

Thus while young Guido was fencing with sword and buckler or droving his horse forward to ram a lance into his quintain around Bologna, his father was far off, fighting on behalf of the Bentivoglio and their patrons in Milan.[41]

In 1499 the Republic of Venice then decided to one-up the Duke of Milan and made an even bigger unforced error than had the Duke. Over the objections of their own leader, the Venetian council made an alliance with the King of France against Milan. Once again the French came over the Alps, and once again their powerful army made short work of their Italian opponent. The Duke of Milan surrendered his capitol without a fight and ran away from the mighty French legions. In exchange for their help and the mortal danger they made to their state, Venice received one small city (Crema) and a handful of French ships to help Venice in its fight against the Turks. As we will see Venice’s choice here would prove to be ruinous and deadly.

With the descent of the French army into Italy there came a man who was destined to cause all manner of trouble for Bologna and the Bentivoglio: a 24-year old stone cold psychopath named Cesare Borgia.

See Bibliography for More Details

[1] According to the Bolognese fencing master Antonio Manciolino blows to the head were worth three points, the foot worth two and the rest of the body worth one. What is not know is whether these values were accumulative between exchanges or whether the difference in value was used to adjudicate double hits (i.e. you hit me in the head, I hit you in the leg, you win because the head is more valuable.) Other masters describing sword and buckler fencing do not talk about relative values, but the face and head are generally the primary targets.

[2] This is a blow-for-blow recreation of Part I of Marozzo’s First Assault for the Sword and Small Buckler. Based on Marozzo’s work we can infer that this is one way that people fought with the sword and buckler. Based on the reasons given in this section we can also infer that Guido and Hugo did cross swords with the sword and buckler. However, we cannot say how it went when they fought so this fictional recreation is simply an educated guess made to illustrate this style of combat. For Part I of the First Assault see The Duel, Swanger pp. 85-86.

[3] Calling them the ruling family is a gross oversimplification. It goes beyond the scope of this work to describe the complex crypto-lordship of the Bentivoglio family in Bologna, which ties into the long traditions of Bolognese independence, and also the history of the Republic of Bologna and finally into the relationship of the Church to the Bentivoglio.

[4] Ghiradacci, p.248

[5] We can fix Guido Rangoni’s birthdate with certainty. For Hugo Pepoli there is less information. The birthdate of 1485 is coming from Wikipedia. Admittedly this is inadequate, but nothing about this birthdate is incosistent with his life and the effort of finding a better source does not seem worth the effort at this time. Guido was born in Spilamberto about twenty-five miles from Bologna and Hugo, presumably in Castiglione dei Pepoli, in the Bolognese contada some seventy-five miles or so from the city itself.

[6] See www.treccani.it entry for “Romeo Pepoli.”

[7] For pilgrimage see Ghiradacci, p. 244. He also escorted Francesca Bentivoglio to Faenza to meet her husband (Ghiradacci, p.223) as well as escorting Giovanni Bentivoglio’s heir to Ferrara to visit his betrothed (Ghiradacci, p.219)

[8] See Ghiradacci, p.339.

[9] Ghiradacci, p.220

[10] Grisoni, p. 12. Note that Grisoni is writing sometime after our time period when the means of training and riding horses had changed. Nevertheless, the need for proper body positioning in time with the movements of the horse was likely a constant.

[11] Grisoni, p.15

[12] Grisoni, p.11.

[13] Grisoni, p.36.

[14] Dall’Agocchie by Swanger, p.75.

[15] See Swanger p.77. Note that in Dall’Agocchie’s time the use of the pouch had been deprecated, but at the time when Pietro Monte wrote his Collecteana, the pouch was still very much in use.

[16] See Pietro Monte’s Collecteana, Translation by Jeffrey Forgent, p. 230. For simplicity’s sake a lance here will be a spear meant to be use on horseback, while a spear will represent a simple thrusting weapon meant to be used on foot.

[17] Dall’Agocchie by Swanger, p. 77-78.

[18] Ibid, p.81.

[19] Forgeng, p.229

[20] Art of Defense, Swanger, p. 43

[21] Francesco Altoni, Monomachia, translation by Fratus. p. 131. Note that the Monomachia is not Bolognese in origin, but geographically and temporally close to the Bolognese masters. Also his statement on the matter accords

[22] Manciolino has an action in his spada da gioco material that appears to cut the opponent’s face by turning this quadrangular blade against an opponent’s face. See Complete Renaissance Swordsman, p.99 for more on the Spada da Gioco.

[23] Marozzo, a successful merchant, seems to envisage a hall about twenty feet on a side, judging by the number of steps he takes to to put you in striking distance of the enemy (six) in his fencing material; the less successful master Antonio Manciolino envisages a hall somewhat smaller, where he needs only five steps to be in position to strike the enemy.

[24] Girolamo Arnaldi, Giosue Carducci's speech for the eighth (virtual) centenary of the University of Bologna , 3rd ed., Società Editrice Il Mulino, 2008, pp. 405-424, DOI : 10.1403/28351 . Citation from Wikipedia.

[25] The bucklers for fighting with sharp swords tended to be large and could be as wide as 24 in diameter, but those for fencing in Bologna were small. For more see Catalogue of European Bucklers by Herbert Schmidt.

[26] This would be about the minimum width required to keep one’s hands safe while performing all the fencing actions described in the texts of the Bolognese masters.

[27] “Earnings of a Fencing Master in XV and early XVI Century,” Battistini Alessandro & Corradetti Niki. Translation by Luca Dazi.

[28] For more on this see See theartofarms.substack.com/p/dardi-deeds & theartofarms.substack.com/p/dardi-deeds-done-dirt-cheap-part?

[29] Earnings of a Fencing Master in XV and early XVI Century,” Battistini Alessandro & Corradetti Niki. Translation by Luca Dazi.

[30] “… for the utility of the young men of this city, and for the honour of the state, and for your own profit” From Stokes translation.

[31] See Complete Renaissance Swordsman {?}

[32] For more on wide play and narrow play see With Malice and Cunning, p.41.

[33] Complete Renaissance Swordsman: p.110, p.115;The Duel, p.99, p. 105

[34] Altoni, translation by Fratus, p.19

[35] Ghiradacci, p.339.

[36] Ghiradacci, pp. 256-257.

[37] Also with Gilberto Pio. However for sake of simplicity we will just focus on Hannibal and Niccolo Maria (Guido’s father) here.

[38] Technically Ludovico Il Moro was not the Duke of Milan, but effectively he was, and the relationship between the Duchy, Ludovico, and Duke Giangaleazzo Sforza is beyond the scope of Death before Dishonor.

[39] See Sabatini, The Life of Cesare Borgia “The French Invasion.”

[40] Who won Fornovo is up for debate but the Italians achieved their strategic goal in this campaign. See Shaw & Mallett The Italian Wars pp.12-35 for a description of the campaign.

See Dedication in Marozzo.