The Great Escape: Part 1

The Tale of Bologna's Greatest Knight: Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi

The Origins of the Marescotti de’ Calvi

The Marescotti were one of the oldest and most powerful families in Bologna. Legend has it that in 800CE, Marius Scoto, brother of William, Earl of Douglas, born in Galloway Scotland, laid down the families roots in the Romagna when he was invested as the count of Bagnacavallo.1 Prior to this grant, in 773, the Frankish King Charlemagne decided to invade Lombardy after the lords in the region reneged on a deal with his son, Pepin the Short, to render some lands that were promised to the church. The emperor asked the King of Dál Riata—or West Scotland—Eochaid IV to commit troops to his campaign.2 Eochaid acquiesced, and tasked his vassal, Count William Douglas, to raise an army of 4,000 men to satisfy his Frankish ally’s request. The Earl started the endeavor, but trouble back home forced him return, and he left his brother Marius, who was described as courageous, tall, and strong, with a reddish beard, to the lead the Dál Riata clans—first to France, then to Italy.3

When the Franco-Scottish army crossed the alps they bivouacked in the valley of Dora Riparia, in the area of modern-day Turin, at the Benedictine Abbey of Noalesa, where they awaited the approach of their Lombard opponents.4 Naturally, Marius started poking around in the hills—killing time—where he managed to find a goat path leading through the bluffs into a nearby forest, and took his highlanders to see where it led.5 After a three-day trek they found themselves at the rear of the Lombard army and sent word to the Frankish king. Charlemagne’s famed cavalry spurred into battle and pinned the Lombards down with a mighty charge while the Scotts, hearing the blaring of horns beget the din of battle, rushed in from the rear to shove it up their arse.6

After this daring defeat of the Lombard lords, Marius became a close advisor and military counselor to the future emperor, and distinguished himself further in campaigns against the Iberians, and the Saxons, before retiring in 799.7 Preferring the food, weather, and women of Italy, he settled down in Rome, and started a family. While enjoying the finery of the eternal city, Marius, a staunch Catholic, became close friends with Pope Leo III, and was given the title defender of the faith. When his holiness was vicar-napped in April of 799, Marius lived up to the billing, after he managed to track the pillaged papa down and saved his tiara.8 As an atta-boy he was given the title, Count of Bagnacavallo, and the right to adorn his family crest with three fleur-de-lis, reserved for French royalty.9 From then on, the scions of Marius Douglas said to hell with the Douglas-bit, we’re the offspring of the great man the Italians call Marius the Scott—thus the Marescotti came to be.

Galeazzo Marescotti de’ Calvi: Early Life

Over the course of the presiding half millennia the Marescotti family slowly moved from their remote county of Bagnacavallo, in the Romagna, to leave an imprint of their legacy on Bologna, Faenza and Imola. It was a natural migration for the family as Charlemagne—after being crowned Holy Roman Emperor—had given land grants in the Bolognese contado to his soldiers as a gift for their loyal service, which meant the sons and daughters of one of the emperors most renowned captains would’ve had some serious political clout with the people who were beginning to settle in the region.10

In 1120 the family added a monument of their occupancy and influence to the skyline of Bologna, when they erected Torre Marescotto in the heart of the sprawling metropolis.11 Then, in 1179, 1227, 1281, and 1290 members of the Marescotti assumed key roles in various levels of city’s civic authority ranging from captain general of the Bolognese army, to podesta, and consul, further entrenching themselves as key figures in the cities nobility.12 The family’s business wasn’t all power games and politics however, they were also members of the Drappieri, or cloth merchant’s guild, as well as prodigious purveyors of lard, and were active in the academic space too, sporting a number of doctors in law and lecturers at the Alma mater Studiorum Uiversità di Bologna.

The proactive progeny of Marius the Scott became mainstays in the City Where YAHWEH Was Staying, but one man in particular stands out above the rest, Galeazzo Marescotti. He was born in 1406 to Lodovico Marescotti, a Doctor of Law, politician, and lecturer at the Università di Bologna, and Costanza da Cuzzano.13 For those of you who have been following our series on Giovanni Bentivoglio and Lancillotto Beccaria, you know this was a turbulent time to open your eyes in the world, and Lodovico found himself at the center of much of the chaos that came in the wake of the Visconti and papal occupations in Bologna.

After supporting a failed uprising in 1413, where he supplied weapons to conspirators trying to overthrow the Papal legate, which led to the murder of the Maltraversi leader, Gaspare Manzolino, Lodovico put his talents to the use for Anton Galeazzo Bentivoglio in 1416, when the Bentivoglio and Canetoli factions united to drive the legate out of the city for good, and again in 1420 when the Bentivoglio took control of the government by wresting power from their Canetoli allies. In 1422, after power was restored to the Pope by Braccio del Montone, the Marescotti were banished from Bologna along with the other supporters of the Bentivoglio faction for causing trouble with the reinstated Caneschi faction—Lodovico was a busy man.

Perhaps due in large part to his father’s proclivities, Galeazzo was sent to apprentice in the art of war with the mercenary company of Francesco Attendolo Sforza at an early age.14 The date, 1422, when the Marescotti were exiled along side the other Bentivogleschi from Bologna for picking fights with the Canetoli, is the most reasonable date for our young Galeazzo to be sent abroad to join a venture company while things cooled-off back home. Not a lot was written about his formative years, the next solid biographical hallmark comes when Galeazzo marries Caterina Degli Anzi Formagliari in 1440, and that’s accompanied by note that he spent a long time in the pursuit of his military career, so we can assume that this means he continued to operate as a soldier of fortune until this time, or shortly before this time.15 This coincides nicely with Annibale Bentivoglio’s return to Bologna in 1438. It’s worth mentioning that there is no record of the birth of Galeazzo’s oldest son Agamennone in Bologna (1434)16, while there are records for his second son Ercole (1438), and the Bolognese government was keen on keeping records.17

We must now turn our attention to Annibale Bentivoglio, who at the age of 11, followed his father into exile from Castel Bolognese to Florence in 1424, and became a mercenary captain at the tender age of 13, leading twenty lances into battle for the first time in 1426.15 You can read more about his early exploits in our article, Dardi Deeds? Done Dirt Cheap, where we discuss the matter in greater detail. What’s important to note here is that Annibale would eventually take up arms in the mercenary company of Micheletto Attendolo in 1431 with his father,16 and continued in this pursuit well after his father was allowed to return to Bologna—where he was subsequently murdered at the behest of Danielle Bishop of Concordia in 1435. Notably, the companies of Francesco Sforza and Micheletto Attendolo often worked in conjunction with one another as they forged a path that would later lead to the establishment of the Sforza dynasty in Milan. It’s likely, though not yet confirmed {more research is needed}, that Galeazzo eventually switched from the service of Sforza to that of Attendolo, to take part in the venture companies with Annibale Bentivloglio.

Before we explore this connection further, let’s take a brief look at Francesco Sforza, the captain we know Galeazzo served under. He was born on 23 July 1401 (three days before the disastrous battle of Casalecchio) in San Miniato al Tedesco to Muzio Attendolo Sforza and Lucia Torsciano.17 Due to his father’s rather harrowing profession, Francesco was fostered in the court of Ferrara by the Marquis Niccolò III d’Este.18 He would remain there until he came of age in 1412, when his father hailed him, and asked him to join his outfit in Perugia.19 This very well could mean that Francesco’s first formative education in the knightly art of combat was taught through the lens of the Friulian fencing master Fiore de’i Liberi’s manuscripts, or even by the fencing master himself.20 Fiore never claims him as one of his famous students, but by the time Fiore completed the Paris Manuscript in 1420, Francesco hadn’t accomplished anything of note, other than being knighted (given his plaque belt and golden spurs) by his father in 1417 for his distinguished service in Naples, which wasn’t exceptional by any means.21

It was likely around this time, that the young Galeazzo Marescotti de’ Calvi showed up in Muzio Attendolo’s camp. {For the sake of brevity} The action picks up in 1420, when Louis III of Anjou and Alfonso of Aragon go head-to-head over the succession of Queen Joanna II, in Naples.22 The pope, Martin V, backed the French prince, and to bolster his claim hired Micheletto and Muzio Attendolo to act as his military muscle in the Neapolitan campaign (we’ll leave it at—they had some scores to settle in Naples), while Queen Joanna had already designated Alfonso of Aragon as her heir, and she hired Sforza’s venerable rival Braccio del Montone to protect his claim.23

From their winter quarters in Aversa, Louis and Muzio laid the groundwork for the campaign to come. First, they sent Francesco and his company—which had distinguished itself time-and-again under the incredibly capable teenager—to Calabria with the fresh title of Viceroy.24 Then, while his son and brother were campaigning in the south, Muzio tried to pin Braccio del Montone down in the north and force him into battle, but the wily captain, known to prefer sweeping maneuvers and small engagements, avoided Sforza at every turn. As a decisive battle proved too elusive, in the winter of 1421, both sides decided to seek peace; Sforza and Braccio reconciled and reminisced about the good ol’ days when they were still pups under da Barbiano, and after some backslapping, the buttered-up Sforza begrudgingly agreed to make amends with Joanna.25

The peace between the two captains wouldn’t last however, they were destined to contend with one another, and when, in 1424, Braccio was besieging the city of l’Aquila, Sforza was called to rally his banners and challenge his vaunted rival once again.26 It was in this pursuit that Muzio’s company came to the river Pescara. Francesco and Muzio took the vanguard across the river and established a bridgehead after a brutal fight with the Bracceschi squadrons guarding the opposite bank.27 Muzio tried to bring the rest of his men into the action, crossing again to lead his more timid soldiers by example, but the river became engorged, as a harrowing wind picked-up from the Adriatic which made fording the swollen waters nearly impossible.28 Recognizing the danger his son and the vanguard were now in, Sforza once-more tried to find a passage across the torrid currents. It was on this ultimate approach that Sforza’s page started to lose his footing, and the great captain—one of Italy’s greatest horsemen—leaned from his saddle to save his life, but in the attempt to preserve his charge, Sforza’s mount slipped and spilled him into the water kitted in full armor.29 The legendary captain drowned beneath in the perilous currents, sources say that twice his greaves breached the water clasped in prayer before he disappeared entirely, confirming his Christmas day vision of being taken to a watery grave by St. Christopher.30

After retreating from the Pescara River, Francesco did what he could to preserve his father’s command and called all the banners of the company together to ask them for their loyalty. Sforza’s troops, known for their honor and discipline, knew how capable and competent the young captain was, and they gave him their oath.31 Rather than continuing the fight with Braccio in Abruzzi however, Francesco had some business he needed take care of at home, and pulled back to Campagna to take possession of his father’s holdings and ensure his titles were passed to his name.32 Once he’d accomplished this, he was directed to attack Naples by Joanna and Louis of Anjou (who was now the claimant to the Neopolitan crown), which had been taken by Don Pietro of Aragon and one of Braccio’s more accomplished lieutenants, Jacopo Caldora. Francesco was aided in his assault by a Visconti fleet under the cunning captain Guido Torelli, who managed to flip Caldora, and sealed the deal by arranging a marriage between Jacopo’s daughter Maria and Francesco. Soon after Jacopo’s defection Naples capitulated.33 Then, the papal army under Ludovico Colonna arrived in theater to help the Neapolitan army take down Braccio del Montone once and for all—it was payback time.34

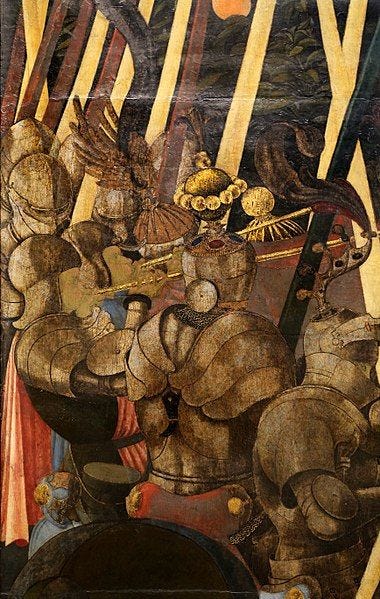

The Battle of L’Aquila

Caldora was given the title Constable of the Neapolitan Army by Joanna, and command of the combined companies of Lodovico Colonna, Francesco Sforza and Micheletto Attendolo as they set off across the Ocre Mountain toward Albruzzi. Braccio del Monotone was still in the process of laying siege to the city of L’Aquila, just west of Rome, and was in a vulnerable spot—the foxlike captain was moored in a fixed position at last.

When Braccio’s scouts spotted the Neapolitan banners, he gathered his captains around a campaign table and discussed what needed to be done. Braccio was convinced that his cohesive force, stocked with loyal Umbrian veterans well trained in his caracal style of cavalry combat that he'd made famous throughout Italy, could handle the Sforza pup, his beleaguered uncle Micheletto, and his old protégé Caldora, without breaking the siege of l’Aquila, but his captains—specifically Niccolò Piccinino—pushed back, and urged him to cut the enemy companies off as they took the St. Larrent pass.35 Braccio’s fear was that pulling away from the city would release the Aquilani garrison and allow the nearly 5,000 infantry combatants to either join forces with the Neapolitan army, or worse harry their rear while they were trying to pin Caldora’s men in the mountains. In the end it was Braccio’s decision, and he opted to stay put.36 The field was set.

It’s worth visiting Braccio del Montone’s innovative strategic and tactical approach as we discuss his dispositions, as both Jacopo Caldora and Niccolò Piccinino will play important roles in later developments of Bolognese history, and both of them were heavily influenced by their time as Braccesci captains. While many condottieri in the later 14th and 15th century had adopted the campaign strategy and heavy cavalry tactics of Alberigo da Barbiano, Braccio del Montone devised a different way to conduct his operations, a way that is very reminiscent of or perhaps better stated as a precursor to Napoleon Bonaparte’s manoeuvre sur les derrie`res, which won the French general so much acclaim. In this manner of warfare, an army is divided into smaller corps, or in Braccio’s case squadrons, which fan out across a campaign objective, controlling sectors, and when it's desired to do so, try to lure a large force into combat so the other squadrons can descend on their flanks or cut their supply lines.

From a tactical standpoint Braccio maintained his small unit command structure and conducted set-piece battles in a similar manner, dividing his army into smaller squadrons that would rotate in-and-out of engagements like the Roman maniple system, or perhaps more akin to the famed Shogunate tactician Uesigi Kenshin’s winding wheel tactic that he deployed to much acclaim at the battle of Kawanakajima nearly a century and a half later.37 The objective was to keep your troops as fresh as possible during the course of the battle, and to wear down the opponents with successive waves, rather than relying on one bludgeoning assault after another, by committing lines to combat.

Braccio was both an innovative tactician and strategist, and a formidable opponent, but his disadvantage at l’Aquila was that Jacopo Caldora knew his tactics, he was in a fixed position, and his opponents significantly outnumbered him. To counter his mentor, Caldora set up his dispositions like this; his Albruzzi company, well versed in the Bracchesci style of cavalry combat, lined up on the left side of the field, opposite of Braccio’s command, while Francesco Sforza and Micheletto Attendolo assumed control of the right flank, and Lodovico Colonna occupied the center with a bulk of the infantry.38 Braccio del Montone’s dispositions were as follows, sixteen squadrons, likely divided into three groups of five, with one held in reserve under Niccolò Piccinino (who had been wounded at the onset of the siege; crossbow bolt in the thigh), to make sure the garrison of l’Aquila didn’t lead a sortie into their rear. His goal was to hold the Sforzesca in check on the right, while his more experienced troops broke the center and left, under Caldora and Colonna.39 The army’s took the field underneath the walls of l’Aquilla near the small hamlet of Bazzano on June 2nd, 1424.

Braccio del Montone’s first wave charged into Caldora’s first platoon, and caused serious casualties, only to peel off for the second wave to strike and break their lances on the beleaguered men-at-arms reeling from the first assault, but before the second line could reach their weary prey, Caldora’s first line pulled away, and his second platoon entered the fray, checking Montone’s momentum.40 As the two companies committed line-after-line they spun themselves into a stalemate. Braccio’s designs of quickly routing the Neapolitan right to roll-up the center, were beaten into a meringue by the competency of Caldora’s captains, welding their rivals art.41

On the left flank Braccio’s captains were facing a different battle all together, rather than the characteristic standoff of two fighters with expert distance and measure trading jabs and checking punches, the fleet footed platoons of the Bracceschi right were pinned against the ropes by two captains expertly trained in the Sforzesca school of hard knocks, which aimed to deliver the pulverizing haymakers and devastating body blows of da Barbiano.42 Muzio may have not been on the field in person, but he was there in spirit, Francesco and Micheletto no-doubt would’ve had countless conversations with the great captain over the years about what how they would handle the Bracceschi tactics in pitched battle, and what they would do when they finally lured the sly fox into a worthy snare. Now they could bring it all to bear, and mourn the loss of the great scion of the house Sforza with the tools he used to lay the foundation of their legacy.

Niccolò Piccinino seeing his great tutors right stall and his left wobble decided that he had no choice but to risk the companies possessions in camp to the frenzied Albruzzi garrison baying for blood at L’Aquila’s gates, and charged the Sforza flank.43 Piccinino’s forlorn assault did little to stymie the emotional vindication of the Sforzesca companies. Thus, as the liberated Aquilani spilled into the Bracceschi camp, and it became clear that Picconino’s gambit had not paid off, the tide of the battle turned from a heavyweight showdown to a route.44 The five thousand strong Aquilani militia, bedecked with riches, found their discipline and formed ranks in the rear of del Montone’s center.45

After seven hours of fighting, on the wheeling left, Caldora had been unhorsed twice, once by Braccio himself, but both times managed to find the safety of his men, and a fresh mount from one of his pages.46 Braccio del Montone, for his part, had fought with the stubbornness of the ram that was emblazoned on his crest, but the successive rutting advances of the great captain’s caracals cost him greatly, and he was grievously wounded in the head or neck in one of his later plunges, and was taken prisoner by one of Francesco’s knights after the young Sforza set off in pursuit of his father’s rival, when his company broke the Bracceschi left.47 As the field collapsed, Francesco had cut a striking figure, and drew the remark, “Who is that man with the black cockade whom I behold wherever I turn my eyes?” from Braccio del Montone prior to being taken captive, to which Francesco is said to have replied, “A worthy son of the great Sforza!” (Pollard, pg. 212). Alas, as the Aquilani garrison tipped the scales and their master’s banner could no longer been seen in the tumult, Bracchio’s veteran companies could endure the field no-longer and fled.

Legend has it that while a camp physician was tending to the captured captain, Braccio del Montone, he found that his skull was fractured, and decided that surgery was necessary to remove bone fragments from his wound. Francesco Sforza was standing-by during the operation, and either out of mercy or spite, pushed the surgeon’s hand, and drove his tool into del Montone’s brain, thus ending the great captain’s life. Other accounts point the finger, for Braccio’s murder, at Armaleone Brancaleoni, Ludovico and Lionello Michelotti, or even Jacopo Caldora himself.48

Regardless of Braccio’s sorted fate, it was important to highlight this seminal event in Francesco Sforza’s career as a condottiere because this was likely the field where our vaunted protagonist, Galeazzo Marescotti, cut his teeth, and learned to ply the trade of the art of arms. We’ve already covered some of the exploits of Micheletto Attendolo in Tuscany with a young Annibale Bentivoglio in tow, in our aforementioned piece called Dardi Deeds? Done Dirt Cheap, and we’ll highlight the remainder of his time in Attendolo’s company in part two of that series in the near future. The big takeaway, whether you read that series or not, is that Niccolò Piccinino, in particular, had some deep seated resentment for the Sforzesca (both Francesco and Micheletto) and every captain that fought under their banners, and in the wake of Braccio’s death at l’Aquila it was his lieutenant, Piccinino, who took up the command of del Montone’s company—the Bracceschi. Now, let's turn to the subject of this piece.

Works Cited:

Marescotti, Galeazzo. Cronaca di Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi. Poemetto latino di Tommaso Seneca e versi di Tribraco Modenese. Inventario dei manoscritti della biblioteca Comunale dell'Archiginnasio di Bologna (serie B), a cura di Lodovico Barbieri, III, Firenze-Roma, Leo S. Olschki, 1945 (Inventari dei manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia, a cura di Albano Sorbelli, LXXV), p. 112-113. https://www.originebologna.com/luoghi-famiglie-persone-avvenimenti/avvenimenti/racconto-di-galeazzo-marescotti-sulla-liberazione-di-annibale-bentivoglio-dalla-prigionia-di-varano-sulla-uccisione-dello-stesso-annibale-e-dei-fatti-che-ne-seguirono//. Accessed 01/05/2024.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009.

Prescott, Orville. Princes of the Renaissance. United Kingdom, Random House, 1969.

Fabio Belsanti. Homes and arms of the Magnificent Lord Messer Michele de li Attendoli di Contti di Cotignola. History, stories, songs and battles of a Company of Ventura in Renaissance Italy. Academia.edu.

The Douglas Archives: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

Chidester, Michael. Fiore de'i Liberi. https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Fiore_de%27i_Liberi. Wiktenauer.com. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Antonelli, Armando. MARESCOTTI DE' CALVI, Galeazzo; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marescotti-de-calvi-galeazzo_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Banti, Ottavio. BENTIVOGLIO, Hannibal; Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 8 (1966). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/annibale-bentivoglio_res-c1afef09-87e7-11dc-8e9d-0016357eee51_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Antonelli, Armando. MARESCOTTI DE' CALVI, Agamennone; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marescotti-de-calvi-agamennone_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Antonelli, Armando. MARESCOTTI DE' CALVI, Ercole; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marescotti-de-calvi-ercole_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Pieri, Piero. ATTENDOLO, Muzio (Giacomuccio), detto Sforza-Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 4 (1962). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/attendolo-muzio-detto-sforza_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 01/02/2024.

Damiani, Roberto. FRANCESCO SFORZA: THE POWER AND PRESTIGE OF A RENAISSANCE DUKE. Condottiereventura.it. https://condottieridiventura.it/francesco-sforza-the-power-and-prestige-of-a-renaissance-duke/. Updated 10/16/2023. Accessed 12/28/2023.

Damiani, Roberto. THE SWORD AND STRATEGY: NICCOLÒ PICCININO’S RISE TO COMMANDING HEIGHTS. Condottieriventura.it. https://condottieridiventura.it/niccolo-piccinino-life/. Upadated 11/29/2023. Accessed 12/28/2023.

Unknown. Battle of l’Aquila June 2, 1424. Ars Bellica: The Great Battles of History. http://www.arsbellica.it/pagine/battaglie_in_sintesi/L%27Aquila_eng.html. Accessed 01/03/2024.

Banti, Ottavio. BENTIVOGLIO, Hannibal—Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 8 (1966). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/annibale-bentivoglio_res-c1afef09-87e7-11dc-8e9d-0016357eee51_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 1/4/2024.

Tamba, Giorgio. FANTUZZI, Giovanni—Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 44 (1994). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovanni-fantuzzi_res-e4c04692-87ec-11dc-8e9d-0016357eee51_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 01/04/2024.

Vitozzi, Elvira. MALVEZZI, Ludovico—Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 68 (2007). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ludovico-malvezzi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 01/04/2024.

Tamba, Giorgio. MALVEZZI, Gaspare—Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 68 (2007). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/gaspare-malvezzi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 01/04/2024.

Tamba, Giorgio. GOZZADINI, Tommaso—Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 58 (2002). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/tommaso-gozzadini_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 01/05/2024

Angiolini, Enrico. GRATI, Giacomo—Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 58 (2002). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giacomo-grati_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 01/04/2024.

Unknown. Origine di Bologa: Foscarari. originebologna.com. https://www.originebologna.com/torri/foscarari/. Accessed 01/05/2024.

Gilbert, Felix. "1. Machiavelli: The Renaissance of the Art of War". Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, edited by Peter Paret, Gordon A. Craig and Felix Gilbert, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986, pp. 11-31. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400835461-003

Ferente, Serena. PICCININO, Niccolò—Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 83 (2015). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/niccolo-piccinino_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 01/01/2024.

Damiani, Roberto. FRANCESCO PICCININO. Condottieriventura.it. https://condottieridiventura.it/francesco-piccinino-di-perugia/. Updated 11/27/2012. Accessed 01/08/2024.

The Douglas Archives: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

In the year 773 king Charlemagne started a military campaign against the Lombards in Italy, because they were not respecting an agreement made with Pepin the Short to give part of their land to the state of the Church. He asked for help from king of Dál Riata (Western Scotland) Eochaid IV.[5]

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

The latter asked his cousin Count William of Douglas to recruit and bring to France a brigade of 4,000 men, which he did. But soon thereafter he had to return to Scotland to govern the family clan, leaving his command to his younger brother Marius Douglas, who at the time was described as courageous, tall, strong and with a reddish beard.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

The army of the Franks crossed the Alps and took base in the Benedictine Abbey of Novalesa, in the high valley of Dora Riparia.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

Mario Scoto, as he was known in Italy, discovered a small path through forests between the mountains which was absolutely unusable by the army, but perfect for the Scottish highlanders.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

After walking quietly for three days along the path, Mario Scoto and his men attacked the Lombards by surprise from the back, while king Charlemagne attacked with the cavalry from the front. It was a major victory for the Franks which marked the decline of the Lombards in Italy.

The Douglas Archives: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

He became an appreciated military advisor and distinguished himself in the Spanish campaign and in the battle against the Saxons at the confluence of the Weser with the Aller in which of the 5,000 Saxons, only the 500 who chose to be baptized were spared their lives.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

Towards the end of the century Mario Scoto retired from the army, married an Italian noblewoman called Marozia and, for his devotion to the pope, settled in Rome where he was granted the honor to escort the pope. He was therefore present when in April 799 Pope Leo III was assaulted and kidnapped near the church of San Lorenzo in Lucina. Mario Scoto was able to find the pope in a monastery on the Aventine Hill and rescued him and returned him to his throne at the Holy See.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

On Christmas Day 800 Mario Scoto was invested Count of Bagnacavallo in Romagna and was granted the privilege to adorn his family crest, which already had the rampant leopard (sic) of Scotland, with the three fleur-de-lis, characteristic symbol of the French kings.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

Charlemagne had received vast lands in the Bologna area and had later distributed them, as was the custom in those days, to the veterans of his army.

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

Ermes, Massimiliano and Oddo Marescotti (Mariscotti) were Consuls of Orvieto respectively in 1035, 1091 e 1099. Carbone - in 1120 build a tower in Bologna. Marescotto - Consul of Imola nel 1140

The Douglas Archive: A Collection of Historical and Genealogical Records. The Marescotti origins (douglashistory.co.uk). Updated 10/4/2023. Accessed 12/16/2023.

Marescotto - Consul of Bologna e Captain general of Bologna in the war against Imola in 1179. Pietro de' Calvi Marescotti - Podestà of Faenza in 1185. Marescotto Consul of Bologna 1227 Guglielmo - Podestà di Siena nel 1232, his son Corrado was Chancellor of Emperor Frederick II in 1249. Alberto Marescotti son of Ugolino was Consul of Bologna, Captain general of the infantry of Bologna, then took Faenza in 1281 and regained Imola in 1290.

Antonelli, Armando. MARESCOTTI DE' CALVI, Galeazzo; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marescotti-de-calvi-galeazzo_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Nacque a Bologna nel 1406 da Ludovico, dottore in legge e uomo politico, e da Costanza da Cuzzano, di antica e nobile famiglia del contado.

Antonelli, Armando. MARESCOTTI DE' CALVI, Galeazzo; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marescotti-de-calvi-galeazzo_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Poco è noto della sua formazione; alcuni dati autobiografici estrapolabili dalla sua cronaca cittadina informano su un lungo tirocinio militare al servizio di Francesco Sforza, che mise poi a profitto al servizio dei Bentivoglio.

Banti, Ottavio. BENTIVOGLIO, Hannibal; Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 8 (1966). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/annibale-bentivoglio_res-c1afef09-87e7-11dc-8e9d-0016357eee51_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Più tardi, per i buoni uffici di Rinaldo degli Albizzi e di Cosimo de' Medici, Antonio poté riconciliarsi col papa e passare al suo servizio: per quanto giovanissimo, anche il B. seguì l'esempio del padre mettendosi al servizio della Chiesa, nel cui esercito militò a capo di 20 lance (1426).

Fabio Belsanti. Homes and arms of the Magnificent Lord Messer Michele de li Attendoli di Contti di Cotignola. History, stories, songs and battles of a Company of Ventura in Renaissance Italy. Academia.edu. pg. 124

Homeni et Armi, 1431186 Gentti d'Arme: Lance in tow:

Aniballo di Misser Anttonio de Bentivoglio da Bologna 21+2/3

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Nacque a San Miniato (allora San Miniato al Tedesco), tra Firenze e Pisa, il 23 luglio del 1401, dalla relazione tra il condottiero Muzio Attendolo, più noto come Sforza, e Lucia di Torsciano.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Poco si sa della sua prima infanzia, parte della quale vissuta con la madre (che Muzio aveva fatto sposare all'amico Marco da Fogliano) a Ferrara sotto la protezione del signore della città, il marchese Niccolò (III) d'Este.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Nel 1412 il padre lo chiamò a sé, prima a Perugia, dove si trovava al servizio del papa Giovanni XXIII, e quindi a Napoli, dove il condottiero si recò, al soldo di re Ladislao d'Angiò-Durazzo.

Chidester, Michael. Fiore de'i Liberi. https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Fiore_de%27i_Liberi. Wiktenauer.com. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. Francesco Novati and Luigi Zanutto both assume that some time before 1409 he accepted an appointment as court fencing master to Niccolò Ⅲ d’Este, Marquis of Ferrara, Modena, and Parma; presumably he would have made this change when Milan fell into disarray in 1402, though Zanutto went so far as to speculate that he trained Niccolò for his 1399 passage at arms.[28] However, while the records of the d’Este library indicate the presence of two versions of "the Flower of Battle", it seems more likely that the manuscripts were written as a diplomatic gift to Ferrara from Milan when they made peace in 1404.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Quando Muzio nel luglio 1417 lasciò Napoli al comando delle truppe inviate al soccorso del papa, insidiato da Andrea Fortebracci, detto Braccio da Montone, il sedicenne Francesco seguì il padre, che lo premiò per le prove di valore offerte conferendogli il cingolo militare e gli speroni d'oro, e nominandolo capitano per meriti di guerra.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009. Pg. 68.

Sforza was far less successful as a politician, and in Naples after the death of Ladislas he inevitably became involved in politics. During these years he was twice imprisoned and was only saved by the steadfastness of his family and his troops, who were able to exert military pressure to gain his release.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

La scena politica e militare si animò in quegli anni per la questione della successione alla regina Giovanna II. Si trovarono a contendere Luigi d'Angiò, designato quale erede al Regno dal pontefice Martino V, e Alfonso d'Aragona che Giovanna II aveva prontamente nominato, in risposta all'iniziativa papale, proprio figlio adottivo e successore. Muzio si schierò con il pontefice e con l'Angiò, e intervenne nella contesa nel giugno 1420 incaricando Francesco e Micheletto Attendolo di occupare Acerra, mentre lui stesso si impadroniva di Aversa.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

Muzio si schierò con il pontefice e con l'Angiò, e intervenne nella contesa nel giugno 1420 incaricando F. e Micheletto Attendolo di occupare Acerra, mentre lui stesso si impadroniva di Aversa.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015. Pg. 194-197

The most graphic descriptions have been preserved to us of the first meeting and reconciliation of the two great captains who had so often been enemies and friends. The first overture was made by Sforza, who entered the camp of Braccio attended by only fifteen unarmed followers. There he represented to his adversary the futility of carrying on a war by which neither could gain much, but both might suffer considerable losses…In reply to these observations, Sforza is said to have reminded him, in a jocular manner, of the different devices by which, when they were in the camp of Alberic, their colors were distinguished…Having concluded these explinations, they are said to have remained a considerable time in private conversation, in the course of which it was agreed Braccio should dispatch letters to the Queen of Naples, entreating her to take Sforza into her favor again.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

On the field of battle he usually found himself opposed by Braccio del Montone against whose fire and brilliance he tended to be at a slight disadvantage. His role in these events was always that of commander of the troops of one or the other political faction in Naples, and he never seemed to be interested in winning an independent state for himself. It was as Great Constable of Joanna II, the successor of Ladislas, that he marched northwards early in 1424, hoping to settle scores with Braccio who was besieging Aquila.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015. Pg. 206.

Five of the best-mounted men in the army dashed into the stream, trusting to the strength of their heavy armor to defend them against the javelins and cross-bows of the enemy: after them came young Francesco Sforza, followed by his father.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015. pg. 206-207

In the moment of his exultation, the elder Sforza beckoned to his followers on the southern bank to lose not time in crossing the river to assist in following up their success; and impatient of delay, he dashed into the water, determined to return again to the other side and lead the way for the timid and doubtful.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015. pg. 207.

The waves which it continued to raise met the flow of the river with redoubled violence; the heavy armour of the warrior and the increased conflict of the waters were too much for the horse, which had already ahd some hours of exercise. Sforza, while in the middle of the passage stooped forward to extend his hand to one of his soldiers, who, being dismounted, seemed to be in danger of being carried off by the current; the animal lost his balance, slipped behind, and precipitated his steel-clad rider into the dangerous eddy. The horse, freed from his burden swam to the bank.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015.

The warrior was unable to struggle with the billows. Twice were his steel-clad hands seen raised above the waters, clasped in together, as if he were imploring assistance…his body was never afterwards found.

Prescott, Orville. Princes of the Renaissance. United Kingdom, Random House, 1969. pg. 91

When the first great Sforza drowned in the Pescara River, his son Francesco immediately appealed to his father’s troops for their loyalty, promised them a glorious future if they would be faithful to him. He was twenty-three years old. He had been a soldier since he was tweleve, had fought in his first battle at fifteen and had already won twenty-two battles.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015. pg. 208-209.

After this he lost no time in marching at the head of his troops to Benevento, which he regarded as the most important of the fiefs of his father, and afterwards visited in the same manner nearly all the other cities that had at different times been allotted to him. Having thus secured himself the allegiance of his troops and his subjects, he proceeded to Aversa, and there made tender of his services to the queen.

Ippolito, Antonio Menniti. FRANCESCO I Sforza, duca di Milano; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 50 (1998). https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/francesco-i-sforza-duca-di-milano_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Treccani.it. Accessed 12/19/2023.

La città di Napoli, controllata dagli Aragonesi, era già assediata dalla flotta viscontea. Il tradimento di Giacomo Caldora, che nell'aprile 1424, incoraggiato da F., aprì le porte del Castelnuovo al nemico, assicurò al giovanissimo condottiero il suo primo vero successo. L'assedio, ora condotto da più favorevoli posizioni interne alla città, determinò l'abbandono aragonese della capitale nel successivo agosto. In quello stesso 1424, riporta il Decembrio, F. sposò una figlia di Caldora, che però abbandonò subito dopo le nozze, in seguito annullate da papa Martino V.

Damiani, Roberto. FRANCESCO SFORZA: THE POWER AND PRESTIGE OF A RENAISSANCE DUKE. Condottiereventura.it. https://condottieridiventura.it/francesco-sforza-the-power-and-prestige-of-a-renaissance-duke/. Updated 10/16/2023. Accessed 12/28/2023.

May 1424: He allies with the papal forces led by Ludovico Colonna.

Damiani, Roberto. FRANCESCO SFORZA: THE POWER AND PRESTIGE OF A RENAISSANCE DUKE. Condottiereventura.it. https://condottieridiventura.it/francesco-sforza-the-power-and-prestige-of-a-renaissance-duke/. Updated 10/16/2023. Accessed 12/28/2023.

Montone allows him to descend from Mount Ocre against the advice of Niccolò Piccinino and other commanders who wanted to attack him on the heights.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015.

So confident was he on this occasion, that, although he knew the forces of his adversaries to be three times as numerous as his own, he sent word to the enemy that, if they would come and attack him in the plains in front of Aquila, he would not oppose their passage through the mountain passes of St. Larrent.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009. pg. 71-72

Braccio believed in diving his army into a number of small squadrons and comitting them to battle piecemeal. In this way he found it not only easier to maintain personal control over the battle, but was able to use his squadrons in rotation and thus rest them during the battle. The effect of this was that they fought fiercely for short spells and then fell back to be replaced by a refreshed squadron.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009. pg. 73.

The tactics of Caldora and Francesco Sforza were inevitably a combination of two schools of warfare. The army was divided into large squadrons and Caldora employed the Braccesco method of constantly rotating the squadrons, so that he always had fresh troops in reserve.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009. pg. 73.

Braccio, with a much smaller army, planned to hold the disciplined impetus of the Sforzeschi in check on his right while he broke Caldora in the centre and on the left.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015.

At the beginning of the battle this expectation seemed likely to be fulfilled. The troops of Caldora, fatigued by the labours of the morning, and unnerved by the perilous situation in which they had been so long exposed, gave way at the first onset. Victory seemed almost in his hands; but the troops of Braccio had in the eagerness of pursuit, come upon an unbroken body of infantry of Sforza: many horses of the former were killed, and a great number driven back in confusion.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009. pg. 73

But he had underestimated Caldora’s mastery of his own tactics and found that, although he gained an initial advantage against him, in the end it was Caldora who had the greater reserve strength to counter attack with devastating effect.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009.

Meanwhile Braccio’s right was also unable to hold the Sforzeschi who began to break through.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009.

As a last resort Braccio’s chief liutenant, Niccolo Piccinino, who had been detailed to guard the rear against an outbreak from the besieged city of Aquila, left his post in an attempt to restore balance in the main battle.

Mallett, Michael. Mercenaries and Their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy. United Kingdom, Pen & Sword Military, 2009.

However, he (Piccinino) not only failed to do this, but also left the rear exposed to a determined rush from the Aquilani, who began to sack the Braccesco camp.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015.

Niccolo Piccinino, one of Braccio’s most promising pupils, anxious to restore the battle to its former success, brought his men from the post where they had been placed by their commander-in-chief to prevent the egress of the inhabitants of Aquila; and the citizens immediately profited by the advantage thus given them, to sally forth upon the rear of the army that besieged them for so long.

Unknown. Battle of l’Aquila June 2, 1424. Ars Bellica: The Great Battles of History. http://www.arsbellica.it/pagine/battaglie_in_sintesi/L%27Aquila_eng.html. Accessed 01/03/2024.

Caldora, who participated directly in the infighting, seems to have been thrown down from his horse twice (and the second time by the hands of same Braccio), luckily escaped the capture just before regaining control of the battle.

Urquhart, William Pollard. Life and Times of Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, with a Preliminary Sketch of the History of Italy Volume 1. United States, BiblioBazaar, 2015.

Young Francesco at the close of the engagement, eagerly pursued the old rival of his father, as if anxious to have the honour of capturing him himself. The latter had cast away his helmet, to prevent his being identified, and met with his death-wound from one of Sforza’s knights, who afterwards took him prisoner.

Unknown. Battle of l’Aquila June 2, 1424. Ars Bellica: The Great Battles of History. http://www.arsbellica.it/pagine/battaglie_in_sintesi/L%27Aquila_eng.html. Accessed 01/03/2024.

According to some sources Francesco Sforza, that he may die soon, would have moved the hand of a surgeon who was operating the Braccio's head. Others told us that to kill him was Andreasso Castelli who wanted revenge because Braccio had killed his family. In Perugia, however, people told that Caldora had killed Braccio because, as prisoner, refused to answer his questions.