What is Viridario, who was Achillini?

How Giovanni Filoteo Achillini Could Potentially Be the Puzzle Piece We've Been Waiting For!

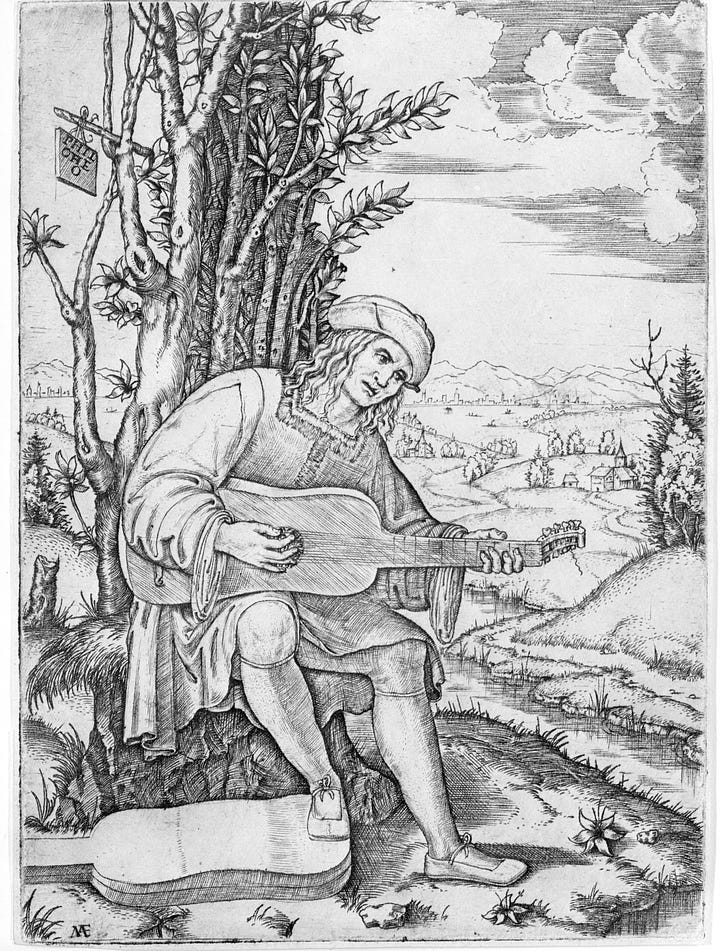

Wow! Thanks to Rob Runacres’ extensive efforts, we have an awesome academic paper to mull over and a new poem about fencing to dissect for time immemorial. It’s HEMA Christmas. What better way to celebrate than with our old friend from Manciolino’s Opera Nova, St. Nicolas —look at him, holding his Holy Falcon Balls! I think that’s what you would call ammunition for a falconet blessed by a saint, right? Holy Falcon Balls.

Either way, Let’s talk about Achilini. Robs paper was great, but I wanted to add a few key historical details, and a really important connection that needs to be discussed. So, let’s hop into our time machine and head on back to Bologna, 2 November 1506.

Amidst the steady barrage of cannonade from the French batteries under the command of Chaumont, the Bentivoleschi hurriedly loaded every available wagon with the family’s invaluable possessions and prepared to flee the city. Pope Julius II’s Bull and Interdict on Bologna was a sweeping indictment of Giovanni II Bentivoglio’s conduct in the previous two decades. After eliminating the Malvezzi and Marescotti families from the Bolognese political landscape, one would assume that Giovanni’s tyranny would’ve been absolute, but all he really managed to accomplish was to undermine his own authority and force an untenable and brash alliance with the French King Louis XII to the tune of 40,000 ducats. This alliance would be the ultimate cause for Julius II’s demand for reclamation, and given the marked presence of Louis’ Captain, Chaumont, at the siege of the city, would represent an alliance that did little but prolong the family’s political downfall and only added the bitter taste of French betrayal—Going way back: Giovanni had allied himself with Milan against France in 1496 when Louis XII’s predecessor, Charles VIII, invaded the peninsula which left a bad taste in the mouth of Charles and his successors. So, fast-forwarding here, Louis’ guarantee of protection, made on account of a desperate plea by Giovanni II Bentivoglio to ward off the forces of Caesare Borgia in 1501, was negotiated at the behest of the French Kings convenience; and now in 1506, it just so happened that this protection agreement had become inconvenient under the reign of of the new Pope, Julius II.

This was the last time the Bentivoglio family would exercise power in a real or meaningful way in the city of Bologna—full stop. True, Annibale Bentivoglio, under the auspice of Louis XII, and the commander of his Italian forces, Gaston de Foix—Oooohhh Gaston—would regain control of the city between June of 1511 and June of 1512, however his brief patronage would prove rather meaningless, and his rule incomplete; he managed to survive a siege, and once again murder a handful of his political opponents, namely the Marescotti, but this proxy was a flash in the pan and was never sustained due to the complete French withdraw from Italy after the death of de Foix at the battle of Ravenna. For five years Annibale had tried, and failed to retake his birthright, and after his brief moment in 1511 became immaterial, he would continue to do so until 1527—but he would never succeed in his efforts. No, from 1506 the Bentivoglio family would represent nothing more than political pawns or war-bands of despotic voyeurs who did nothing but provide a further threat of instability and violence to a city already tired of war.

This may sound harsh, but Annibale tried seven times; the initial attempt in 1507, followed by a failed coup in 1508, then the Venetians gave him purchase to act as a decoy in the Romagna in 1509, the failure of which led him to switch sides and join the French who managed to briefly put him in power in 1511, then in 1513 he begged the new Pope Leo X to reinstate him—which was denied, followed by an attempted insurrection in 1522, and finally a failed assault in 1527 which was thwarted by Ugo Pepoli. Annibale believed that history would repeat itself, that the Bolognese people would welcome him back as a hero, like his great-grandfather Giovanni I, or his Grandfather Annibale I—the Hero of Bologna, or his Cousin Sante Bentivoglio. However, the missing piece that undermined his efforts time-and-again was the tangible spine of Bentivoglio power, it was their allies who were there to save them every step of the way; the hero’s that climbed castle walls to assault tower dungeons, who shouted, “Sega, Sega, Sega!” as they crossed the rushing waters of the Reno, the Malvezzi and the Marescotti—and we can see through Annibale’s actions in 1511 that despite his lack of success, he failed to learn this lesson yet again.

While the Bentivoglio were never fully welcomed back into Bolognese society, some of those courtiers who responded to the Pope’s initial interdict and series of excommunications, who fled the city with the Bentivoglio family, were. One important character of note in the sad cavalcade of exiles trundling through St. Felix’s gate was Alessandro Achillini, the brother of our famed poet Giovanni Filoteo Achillini—the true subject of this piece. Alessandro is an important subject because of his considerable fame, to contemporary scholars he was known as the second Aristotle. As such, we have a lot of data to work with about Alessandro’s life, more-so than we do for Giovanni Filoteo. For example, the University of Bologna’s Famous People and Alumni page gives us some wildly useful information:

His role as a renowned humanist intertwined with that of an indispensable courtier of the Bentivoglio court and a great supporter of the Università degli Artisti, in which Achilini was enrolled. This inevitably led to his escape when, in 1506, Pope Julius II regained possession of the city, sending not only Giovanni II and his family into exile, but also nobles and intellectuals who had been their supporters.

Achillini thus fled to Padua, where he was offered the professorship of Natural Philosophy, previously held by Pietro Pomponazzi.1

Now, let’s add to this the fact that after the failed 1507 assault on the city of Bologna, that Annibale and Ermes Bentivoglio fled to Mantua, until their presence brought interdicts down on their Gonzaga family members, and they were forced to relocate, settling down in the Verona-Padua area; not far from their friend Alessandro. It’s just really hard to draw correlations here, isn’t it? Its not—not by any means, in fact the web of connections is getting so tangled that it’s starting to become suffocating. Allow me to lay this out for you, so we can untangle this a bit—then I'll draw you to a hypothesis that fits the historical narrative, hows that?

1496 Annibale Bentivoglio has a building constructed which he deemed il Casino, it was built for his pleasure, and that of his friends, so that they could practice with weapons and exercise, and do similar things—Giradacchi, A History of Bologna2

The name Guido Antonio di Luca first appears in Bologna in a census conducted 1496, his residence is in via Saragozza, under the parish of Santa Maria della Muratelle. He dies in 1514. According to Marozzo, di Luca had more students than warriors that came from the belly of the Trojan Horse. Jacopo Gelli, who is not always a reliable source specifically mentions Guido Antonio di Luca as, “Being under the the protection of the Bentivoglio”.3

1504 Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, brother of Alessandro Achillini; a Bentivoglio courtier, completes Viradario, which is a poem with mythological stanzas followed by a list of exemplary citizens who possess the virtues of the allegories within—including one, Guido Rangoni. Check it out!

Guido Rangone questi carmi uale, Come e ne gli atti delicati stanno, Non ha leta sua giovenerto equale, Lieto e quiui infudato in dolce affanno, Hora contermo quel dritto morale…4

The bulk of the poem is comprised of a passage about Sword and Buckler Fencing, the core pedagogical tool for teaching fencing in what we can recognize as Guido Antonio di Luca’s Schermo, and we know that Guido Rangoni and Achille Marozzo were both students of di Luca.

In the same year, 1504, Giovanni Filoteo Achillini was working as an editor for Caligula Bazalieri, on the works of Serafino Aquilano; which notably was the first time we see Niccolo ‘lo Zoppino’ Aristotile d’Rossi listed as ‘impressor and seller of books’. d’Rossi was an apprentice of Bazalieri, and would eventually print Antonio Manciolino’s Opera Nova in 1531.

Guido Rangoni was the grandson of Giovanni II Bentivoglio, and was given a humanist education in the city of Bologna and learned the art of swordsmanship from Guido Antonio di Luca. He earned his first condota, or contract, with the Bentivoglio in 1500, and remained loyal to the family until 1509 when he re-entered Venetian service while his uncles allied themselves with France.5

In 1506 the Bentivoglio Family was forcibly removed from Bologna. Six-hundred loyal Bentivoleschi fled the city with them, including Alessandro Achillini, and members of the dall’Agocchie family.

1508 Alessandro Achillini returns to Bologna and begins teaching Philosophy and Medicine at the University of Bologna, where he takes on Lodovico Boccadiferro—one of Viggiani’s muses in his lo Schermo—as a student in both disciplines until his death in 1512. This is the same character that relates Aristotle's physics to us as a way of describing tempo in fencing. 6

Despite having finished his work in 1504, Giovanni Filoteo Achillini publishes his work Viradario in 1514. The book is published by the Bazalieri family.

It’s believed that between 1522-1523 Antonio Manciolino publishes the first edition of his work, Opera Nova. However he signed a contract with Stefano Guillery, in Rome, for a print run of 1000 copies of a book on the Gladitorial Arts in 1519. No copies of this early run are known to exist.

1531 Manciolino republishes his work with Niccolo ‘lo Zoppino’ Aristotile di Rossi. In the same year, Achille Marozzo is given a permit to purchase a mill in the city of Bologna, which is a significant event as it essentially raises him from the popolani to the divites populares.7

1536 Achille Marozzo publishes his Opera Nova.

So, what do the Achillini brothers bring to the table that we didn’t have before? The breadth and depth of Bentivoglio loyalty. Reasonably I can state that they were peers of Annibale II Bentivoglio; Alessandro was born three years prior, and Giovanni Filoteo was the same age, both grew up in Bologna, and came from the Bolognese elite. Alessandro would go on to become a famous philosopher and anatomist, while his younger brother took on the role of Renaissance man; singer, poet, philosopher, writer, editor, ect. He was by all of the known contemporary standards just a well trained courtier, was he not? We praise—whelp, Charles V and Viggiani praise—Luigi ‘Rodomonte’ Gonzaga, for his excellent skills as a courtier, he perfected the art to such a degree that he won the affection of Kings and Emperors, and became the first knight in Italy in the minds of those in power. Baldassare Castiglione, who wrote the Book of the Courtier, was friends with Rodomonte—he gave him a hunting dog before he left for Spain—was Giovanni Filoteo’s youthful enterprise any different than Gonzaga, does he too not fit Baldassare’s mold? Shitty poet—perhaps, but skilled courtier—more-like. Giovanni Filoteo would reinvent himself or perhaps just self-actualize in the wake of the Bentivoglio collapse and his brothers death in 1512. He would go on to serve diligently in the municipal government as a member of the Anziani in the years; 1513, 1516, 1522 and 1524, then he would reach the highest civilian office in Bologna in 1527 when he became Gonfalonieri del popolo, and would conclude his political career in 1537 serving one last term as a member of the Anziani. Perhaps we don’t know enough about our shitty poet to ascribe him such a demonstrable epitaph—

What we do know is that Giovanni Filoteo and Alessandro Achillini were privileged to the inner circles of the Bentivoglio family. Inner circles that may have allowed Giovanni Filoteo to observe a nineteen year-old Guido Rangoni practicing sword and Buckler in Guido Antonio di Luca’s salle. His youth has no equal life, Happy and here engulfed in sweet anguish. What does Viridario represent to me? The closest we’ve ever gotten to visualizing this art in practice. My hypothesis: Bolognese Fencing is not dead, it’s never been more alive! Giovanni Filoteo Achillini is not a dagger in the colloquial paradigm, it’s another puzzle piece that brings together a Bentivogleschi system of fencing, and there is no Bentivoglio without Bologna. The historical narrative surrounding the characters, paradigms, and scions of Bolognese fencing are made more clear and transparent by the existence of this poem.

Now, the burden of proof is never on the cynic or the critic, it’s always on the defender of the established position, is it not? Mission accepted—and to you dear reader, I hope you’ll join us on this journey. There is still so much to explore here.

Holy Falcon Balls!

One last note before I go. This is the second time this month I’ve encountered historiographical evidence that gives us a clearer picture of the background of these authors, or their analogous direction(s), all in identified treatises that weren’t mentioned because either the author(s) didn’t have time to examine the whole document outside of the fencing portion, or in their estimation found the totality of the document to not measure up to the effort. For you young up-and-coming translators out there, there is ample opportunity to bring us closer to these characters, even in the extant treatises we have on hand, so—go forth! Help us better understand the H in HEMA, so we aren’t perpetually misdirected by only focusing on the MA.

Alessandro Achillini: https://www.unibo.it/en/university/who-we-are/our-history/famous-people-and-students/alessandro-achillini-1

Ms. Codex 1462 - Ghirardacci, Cherubino 1519-1598 - Historia di vari successi d'Italia e particolarmente della città di Bologna: Link

by Jacopo GELLI - Nedo NADI - * - Italian Encyclopedia (1936) https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/scherma_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/

Achillini, Giovanni Filoteo. Viridario de Gioanne Philotheo Achillino bolognese. N.p., n.p, 1513.

Guido Rangoni: https://condottieridiventura.it/guido-rangoni/

Ludovico Boccadiferro: https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ludovico-boccadiferro_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Achille_Marozzo