Introduction:

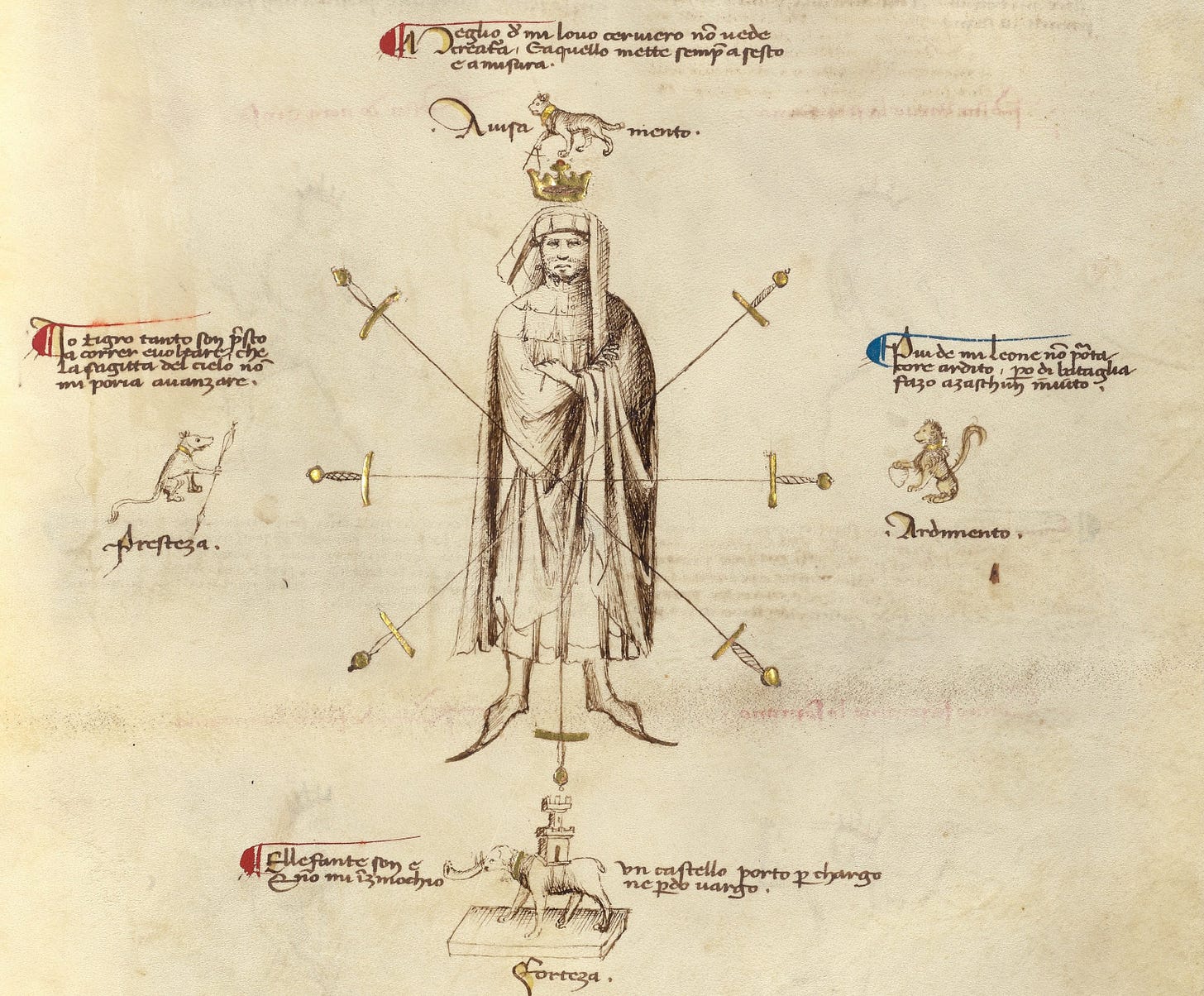

Prudence, Celerity, Fortitude, Audacity.

Those are the four principle virtues purported by the Friulian fencing master Fiore dei Liberi, in his Flower of Battle or Flos Duellatorum.

He declares, “the four animals signify {the} four virtues, that is prudence, celerity, fortitude, and audacity. And whoever wants to be good in this art should have part in these virtues.” (Fiore; Chidester, Wiktenauer)

Prudence/Wisdom

No creature sees better than me, the Lynx.

And I always set things in order with compass and measure.Celerity/Speed

I, the tiger, am so swift to run and to wheel

That even the bolt from the sky cannot overtake me.Audacity/Daring

None carries a bolder heart than me, the lion,

But to everyone I make an invitation to battle.Fortitude/Strength

I am the elephant and I carry a castle as cargo,

And I do not kneel nor lose my footing.

Medieval and Renaissance Sword fighting manuals are full of allusions to virtue, be they personal or martial, thus its worth examining the origins of virtue to define what they are, and explore the contextual framework from which they came, so we can better understand how they relate to fencing and see how they complement a greater martial ethic.

In the modern secular world, the principles of virtue have—to a degree—lost their relevance and luster, they’re often relegated to religious practice or seen as a relic of classical ‘westernism’. Some of the virtues we’ll cover in this article have even come to take on negative connotations—like audacity and prudence—so it’s fairly reasonable to presume that the lessons of the virtues embedded in historical texts can be or are often overlooked or misunderstood. Alas, they’re important—they in-and-of themselves carry significant contextual information which can illuminate the strategic vision of a given fencing author and deserve to be studied.

Unfortunately, the challenge of relating the concept of the moral or ethical virtues to the practice of fencing is that they are in essence cooperative standards, and fencing by its nature is an individualistic expression of art. That is, the individual standards of virtue are designed to ground and better the individual for the benefit of the whole society. So, how can this sense of self-improvement and self-regulation co-mingle with the ideas of self-preservation? While many of the authors covered in this article will argue effectively in the affirmative, one author in particular, the anonymous author of MSS Ravenna M-345 and 346, will argue for a different approach—taking a more classical or even Machiavellian view.

This trend toward cooperation, is further exacerbated by the great Theologians of the first millennia. As such, it's possible that many of our contextual renderings of the martial virtues have been misconstrued or miscalculated due to an over reliance on the theological philosophers, when the real focus should be on their secular counterparts. To thoroughly examine this claim, we’ll review a few of the writings of those secular authors from the 14th and 16th centuries, and see how their concepts of virtues stack up against their theological and martial counterparts.

The objective of this article is to explore virtue from its origins to its contemporary expression in the age of the fencing authors and construct a vehicle for virtuous understanding that can benefit the development of the modern martial arts practitioner. An analysis that may challenge your fundamental understanding of what a virtue is and provide insight for future translations and interpretations.

The Origin of Western Virtue:

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, virtue is associated with aretḗ in Greek (ἀρετή), which is a derivative noun of Ares (the Greek god of war) and etymologically builds its roots from aristos and aner, meaning—essentially—best and man, sometimes derived as manliness or andreia—we can reimagine this as a complete person.1

Alternatively, the venerable PhD Classicist David Stifler notes that this is incorrect, that, “ἀρετή comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *h₂reh₁-, which meant something like "to think, to reason, to arrange" and is found in other Greek words such as ἀραρίσκω, meaning "to join, to fasten, to equip, to fit, to make pleasing, to make suitable," etc. and ἀρέσκω, which means "to satisfy, to please, to make amends" etc.” He continues, “What's perhaps even more interesting is that the same PIE root h₂reh₁- also lies behind the Latin verb reor, "to think, to deem," from which is derived the noun ratio — which (…) means "reasoning, plan, view, advice, doctrine" etc.”

Doctor Stifler’s etymological analysis fits better with the classical expression of virtue, as we’re about to see. Notably the etymological root reor and it’s derivative ratio.

The four cardinal virtues; or chief categories of virtue, were first recorded by Plato in his Republic, sometime between 370-380 BC.2 They are Prudence (φρόνησις), Justice (δικαιοσύνη), Courage (ἀνδρεία) and Temperance (σωφροσύνη). To Plato, these were principles that were indicative of the health of a polis, and were often exemplified by certain classes within the community, e.g. wisdom unto the rulers, courage unto the soldiers, moderation for all; so they may agree on proper governance, and justice which he rendered as, “doing one’s own work, and not meddling with what is not one’s own.” (McLeer)

Moreover, just as the divisions of virtue enrich the polis, so too are they manifest within the soul. That is, in order to achieve ones highest existence one must cultivate a balance of all four virtues within themselves.

These cardinal virtues would be further expounded upon and expanded by Aristotle in his, Nicomachean Ethics, sometime between 335-322 BC, and brought within a more moral and individualistic framework.

Aristotle postulated that knowledge of the virtues was attained by observing virtuous exemplars and through experience. They were essential traits for a person to achieve Eudaimonia (εὐδαιμονία) or self-fulfillment and happiness. To Aristotle, the virtues were a characteristic mean flanked by vices of extreme—this is known as his golden ratio. For example, the deficiency of courage is cowardice, and the excess of courage is recklessness, therefore a positive expression of courage rests between these two vices. If one were to charge headlong into a phalanx alone—that would be reckless, if one were to avoid battle at the risk of the wellbeing of their peers or community then that would be cowardice, but courage would be standing shoulder to shoulder with their fellow hoplites and facing danger head-on even at the cost of ones life.

Aristotle lists 12 key virtues, they are: temperance, courage, magnificence, magnanimity, justice, friendliness, truthfulness, wittiness, prudence, modesty, and shame.

In Aristotelian ethical philosophy the pursuit of eudaimonia is a lifelong journey of self-improvement. The Virtues were guideposts to strive for, and through rationality; an exercise of the golden mean, and experience these inexplicable formative standards would come to be realized.

Wisdom of Solomon 8:7

7 And if anyone loves righteousness, her labors are virtues; for she teaches self-control and prudence, justice and courage; nothing in life is more profitable for mortals than these.

The Cardinal Virtues would appear in the Abrahamic tradition—together—in the first century BC in the Wisdom of Solomon; a part of the Septuagint and would later be adopted by the early Christian Church as the seven virtues and vices by the 4th Century Theologian, Ambrose.3

In the Christian tradition the heavenly virtues are charity, temperance, chastity, diligence, patience, and kindness. The vices contemptuous to or deficient of these virtues are pride, greed, envy, wrath, lust, gluttony, and sloth.

In the 13th Century, St. Thomas Aquinas argued that a good life hinged upon the four cardinal virtues—prudence, justice, temperance, and fortitude—and that these critical traits were ensconced in the Godly virtues of faith, hope and love. Aquinas derived these standards from the reflections of St. Augustine, Boethius, and Anselm, and merged Aristotle's Eudaimonia with the contemporary ecclesiastical reflections.4

Of course, through the 12th century these virtues were also adopted-into and coalesced-with the moral exemplars of the Arthurian and Carolingian epics and co-opted into the temporal landscape of knightly or martial virtues: courage, justice, mercy, generosity, nobility, hope, and humility; among others. For example, the five virtues that Gawain was challenged to embody were: fellowship, purity, courtesy, pity, and franchise,5 while those portrayed by Roland in the wildly influential epic, the Song of Roland, were: valor, loyalty, piety, self-sacrifice, and a strong sense of duty to his lord and faith.

The necessity of these epics among the emerging class of chevalerie was—in large part—due to the fact that the martial reality of the emerging Medieval world often came into conflict with the ecclesiastical reimagining of the pagan philosophers and canonical ethic. It was at this inevitable crossroads that the Germanic and Celtic lore provided a certain je ne sais quoi for the virtue ethic of the warrior class. While the Celtic legend of Arthur was retroactively imbued with the theological guidelines of the Christian faith, much like Beowulf, it's incorporation as such was—in a sense—a compromise between the extant pagan warrior ethic and the moral standards of the emerging Christian world. A notion made further evident in the Carolingian Epic, the Song of Roland, which—while deeply Christian in it’s conception and composition—struggles to shed it's themes of Germanic paganism. It was through the commingling of these worlds that the ideals of Chivalry were born.

This history, while brief, stands to highlight a core tenant of this article, the difficulty of separating the pagan (Roman, Greek, Celtic, and Germanic) from the Christian forms of virtue—especially martial virtue. While the contemporary theological expressions of virtue were inspired by their pagan ancestors, it was the theologians who were more equipped to promulgate a virtuous standard and as such tipped the scale. Alas, the reality of the post-Roman world, and the amalgamation of Christian, Roman, Celtic and Germanic cultures required some sense of compromise to construct a functional polis. Thus, we can view a slight diversion between the moral mean of the serf, citizen, nobility (in some areas) and clergy, and their dedicated martial peers.

Defining the Virtues:

(O)ne who will possess these said qualities will fill his art with glory and honor, because in the discipline of these martial arts they demonstrate the erudition and intelligence which are the principles to the adornment that are the self-evident fruits of the workings of those principles. (T)hose principles being courage, cunning, strength and skill; and from these come the roots which give the delightful fruits; the glory of courage is to have cunning and wanting to enrich this cunning with a crown of pure gold, we will accompany it with a fortress; and wanting to embellish this fortress and give to it the fountain of life we will accompany it with a faithful escort of intelligent skill of such art that its ornament is salvation.

—Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 13

While Aristotle alludes to the fact that the virtues are undefinable, as they are relational and best learned through practice and observation, it will aid our discussion of the virtues of fencing if we have some sense of what they are. To do this, let’s examine the four most common virtues (For a full list of virtues by author see, Appendix: list of virtues by author). They are {unsurprisingly} Prudence, Celerity, Fortitude and Audacity. Note, that the challenge of defining a virtue, is that their meaning has a tendency to change over time, so it’s best to create or derive a definition that is local to the authors virtuous epoch. Yet, even this approach is imperfect, as experience—the mother of all wisdom (to quote Manciolino), allows for a high degree of emphasis and deviation.

Fortitude:

This is the moral virtue of courage. However, there is a fair amount of depth embedded in the Latin root fortitudo. Thus, in order to create a workable definition, we’ll have to examine both the spiritual and temporal expressions of Fortitude and explore how they were understood and where they differ.

Plato defines fortitude as, “the principle of not fleeing danger, but meeting it.”

In Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Book I, Chapter 9, he states, “Courage is the virtue that disposes man to do noble deeds in situations of danger, in accordance with the law and in obedience to its commands.” In Nicomachean Ethics he states, “Hence someone is called {fortuitous} if he is intrepid in facing a fine death and the immediate dangers that bring death.” (Eth. Nic., III, 6; Irwin)

Aristotle argues for a number of different characteristics of courage predicated on the type of fear present and the response’s relation to the mean of fortitude. Aquinas takes these and gives four key divisions; Audacia (Audacity) and Timor (Fear), Agreddi (Attack) and Sustinere (Sustain/Endure), and concludes, principalior actus fortitudinis est sustinere, immobiliter sistere in periculis, quam aggredi (The more important act of fortitude is to endure, to stand immobile in dangers, than to attack). (Rickaby; pg. 3)6

His reason for this conclusion is, “the act of endurance rests only with the reason per se.” (Rickaby; pg. 3) This justification is in part a descent of Aristotle's supposition that anger can be used as a tool in the virtue of fortitude, speaking of the battle rage which Aristotle believed could be harnessed and wielded for the greater good; what Aquinas terms the irascible passion. Notably, something the Roman thinker Seneca also takes exception to, relating that sense of audacia implied here to the vice of recklessness.

There is an important distinction drawn by Aquinas in his observation of the tangential manifestations of Fortitude that bears some further examination—that is, agreddi and sustinere. To attack and defend. To further understand this, we should first examine the thoughts of our first secular thinker.

The best example of a temporal scholar contemporary to Fiore’s time is Giovanni di Legnano, a professor at the Università di Bologna who was a renowned lawyer and jurist in the late 14th century. Legnano’s works like, Tractatus de bello, de represaliis et de duello (d. 1383), we're so widely known that he was mentioned in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. In Tracatus de Bello he states:

But as it has been said that fortitude and arms are the chief foundations of war, and as in law the nature of fortitude is not explicitly discussed, it is desirable that its nature should to some extent be explained. And I ask, first, whether fortitude is a moral virtue ; and it appears that it is not…

But four extremes are opposed to fortitude, namely, fearlessness and timidity or fear, and audacity and deficiency in audacity, which has no proper name, as the text shows in Ethics, book iii. The Philosopher proves the opposite in Ethics, book iii. For the solution of the question we must observe that the meaning of “ fortitude " is equivocal ; it may refer either to the fortitude which is the same thing as strength of body, or to the fortitude which is moral virtue. The first is a power which enables one to move a thing, as the Philosopher proves in Rhetoric, book i ; and both kinds are required in war ; and so when I said that fortitude, or strength, and arms are the foundations of war, I used the word generally, since both kinds are required . But as to the first, which is the strength of the body, there is no doubt that it is not moral virtue, for the reasons given above ; but as to the second, the question must be continued ; and it is the virtue which makes us behave aright in the matter of fear and audacity in the dangers of war. Let us pursue this kind of fortitude, for the first is plain to the blear-eyed and to barbers. Now for the understanding of the fortitude of the soul, we must observe that, in the matter of daring and fearing, one may exceed or fall short ; and in either case one acts wrongly. One may also keep oneself to the mean, and so act virtuously.

Audacity, however, differs from fear ; for audacity is a feeling of the irascible appetite, inclining us to attack what is terrible. Fear inclines us to flee, as any one may experience in himself. But either may be a good or a bad act ; for if a man were to see ten armed men and attack them alone, that would be a bad act ; and if he were not to flee , it would be a bad act, bad as regards the attacking, and also bad as regards fear. So, again, a man may exceed in fearing ; as, for instance, if there are a hundred men in a fortified place, and they see only a hundred men against them and flee—that is a bad act. So, too, by not attacking ; as if they see a city being spoiled and do not attack—that is a bad act. So you have illustrations of excess in not fearing when fear is expedient, in fearing when fear is not expedient, in attacking when attack is not expedient, and in not attacking when attack is expedient ; and so you have the extreme vices, audacity and fear, and degree in each case, as above"

—Legnano; Brierly and Holland, pg.238

Here we have a insightful delineation between the moral and physical expressions of fortitude, as they relate to the conduct of warfare. The fortezza or strength of body to endure and withstand the risks and rigors of combat, and the moral courage to forfeit ones own life in the pursuit of a noble cause. Legnano argues that the virtù of fortitude as it relates to war should not be conflated with the moral virtue of fortitude, because a strict adherence to the mean between fearfulness and audacity is a detriment when faced with the complexity of the conduct of war. Aristotle, in concert with this acknowledges that professional soldiers (ie. mercenaries) are inclined to this ambiguous nature, and that it is the local militias who are more attuned to the necessity of fortitude’s virtuous mean on account of their role in protecting the homeland.7

Philippe Contamine, in his seminal work, La guerre au Moyen Age, argues that contemporarily it was understood that the ‘physical’ acts as a wellspring for the ‘moral’, stating, “Among the 4 cardinal virtues inherited from Antiquity, force (fortitudo) covers the notion of courage. Force gives both fearlessness and bravery in war.”

This is an interesting observation that aligns nicely with Legnano and Aristotle, but draws some contention with the Saints of the Holy Mother Church. While they agree on the notion that Fortitude is the the ability to endure hardship and physically overcome the risks of death, it’s in the proper conduct born from the potentiality of fortitude where they differ. Contamine, Aristotle and Legnano seem to believe that fortitude allows one to be bold, audacious, and brave, but also to regress to the mean of the virtue—with temperance and prudence—when necessary. Where Aquinas believed that, “fortitude is about fear and daring, as curbing fear and moderating daring.” (Aquinas; Question 123; Article 3)

This is where Aquinas’s observation that there is a modal reality to fortitude—agreddi and sustinere; attacking and defending—could lend some insight into the inclusion of the virtuous extreme of audacia (boldness) as a martial virtue in concert with the moral and physical mean of fortitude. In that, fortitude is about holding ground, and enduring or sustaining—defending—rather than taking risk.

One could argue that this is precisely what Fiore dei Liberi was illustrating with his segno, where fortitude is attributed to the lower half of his idealized fencer, as it's the foundation or the root bed from which courage, strength and endurance of both body and soul will emerge. He attributes both fortitudo and fortezza to the symbol of the elephant, and says, “I am the elephant and I carry a castle as cargo, And I do not kneel nor lose my footing.” (Chidester; Wiktenauer) The inability or refusal to kneel or bend a knee is moral courage, and the strength to not lose ones footing aligns with the physical strength and endurance attributed to the temporal expressions of fortitude. It also implies not giving ground—Sustinere.

Building upon this notion, Antonio Manciolino also identifies fortezza and fortissimo as key attributes of a fencer at mezza spada8, and embeds their more tempered expressions in his, Gravi and Appostati.

Fencers who deliver many blows without any measure or tempo may indeed reach the opponent with one of their attacks; but this will not redeem them of their bad form, being the fruit of chance rather than skill. Instead we call gravi & appostati those who seek to attack their opponent with tempo and elegance.

—Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 112

As Tom Leoni notes, in his Complete Renaissance Swordsman, “Grave means, in this case, composed in his control and mature in his actions. Appostato means consciously observing the right posture and tempo.” More adroitly, Doctor Stifler highlights the etymology of Appostare’s military root, which is a post or a station9, and derives a contextual meaning of “serious and on point.” Which lends further credence to this supposition of sustinere.

Viggiani, expounds upon this notion in his book one dialogue between the philosopher Boccadiferro and the soldier Rodomonte. When attributing the virtues of a fencer to parts of the body Boccadiferro states, “Finally, the foot stands for self-control, balance, and good timing. If the foot is controlled by anger and moves without thinking, without measure or restraint, then it would act like a venomous snake or a lion. A smart enemy could easily take advantage and defeat someone like that.” (Viggiani; Book I, Fratus)

Notice the moral mean of fortitude in both Manciolino’s maturity and composure and Viggiani’s control and restraint, as well as their focus on the physical necessity of balance and posture. Viggiani explicitly derides the virtuous extreme of audacity—(i)f the foot is controlled by anger and moves without thinking, without measure or restraint—a trait he attributes to the characteristic ‘boldness’ of a lion.

This is not to say this fortuitous approach can be done without courage—to the contrary, Boccadiferro continues:

“RODO: That’s true, but I also think a good soldier needs to be strong, tall, healthy, fast, and have other good physical traits—not just the inner ones you mentioned.

BOC: Of course, you’re right. And while you do have those qualities, not everyone is lucky enough to be born with them. But many of these physical traits—like strength and agility—can also be developed through training and practice, not just from nature. Still, those three basic things we talked about—the eye, hand, and foot—are the most important for the job.

Think about it: what good is a big, strong man if he’s a coward? What would you think of someone who was fast and strong but who lacked courage and wisdom? And what use is someone who’s large, strong, handsome or healthy but who lacked the self-restraint imposed by reason? No matter how healthy or handsome he is, he can be dangerous or useless. The truth is, a person’s mind and wisdom are what make him better than wild animals. That’s why a good soldier must have courage, knowledge, and self-control.

Plato explained this well in his book The Republic. He said that a true soldier needs three things: anger to fight the enemy; gentleness for friends and fellow soldiers; and philosophy, that is wisdom, to tell the difference between right and wrong, friend and enemy, and what helps or harms.”

—Viggiani; Book I, Fratus

Here we have the necessity of physical and moral fortitude in harmony with traits characteristic of the other virtues. It is both strong (fortezza) and enduring (sustinere), but also courageous in the face of danger, neither fearful nor audacious, but inclined to the mean through temperance and good judgement. It's the foundation of a well composed fencer. Through its exercise a fortuitous fencer will neither be inclined to flee nor bend the knee, but to stand resolute and strong—courageous in the face of death and whatever ills are imposed upon them.

The dangers of death which occur in battle come to man directly on account of some good, because, to wit, he is defending the common good by a just fight. Now a just fight is of two kinds. First, there is the general combat, for instance, of those who fight in battle; secondly, there is the private combat, as when a judge even private individual does not refrain from giving a just judgement through fear of the impending sword, or any other danger though it threaten death. Hence it belongs to fortitude to strengthen the mind against dangers of death, not only such as arise in general battle, but also such as occur in singular combat, which may be called by the general name of battle. Accordingly, it must be granted that fortitude is properly about dangers of death in battle.

—St. Thomas Aquinas, Question 123. Fortitude

Audacity:

(F)rom Medieval Latin audacitas, from Latin audax (“bold”), from audeō (“I am bold, I dare”).

—Etymology of Audacity; Wiktionary

If fortitude is the mean and the standard of courageous virtue, then how can we rectify another expression of courage, especially it's extreme—audacity or boldness?

The dichotomous distinction of Audacia that is common in modern nomenclature is inherently Roman. Cicero, who laid the foundation for much of the rhetorical and legal framing constructed during the 12th-16th century, saw Audacia as both a vice and a virtue, dividing it’s qualities between the vice of impudence—often characterized as a criminal or atrocious quality—and that of the battlefield, relating audacia to courage, boldness or valor.10 Seneca the younger, in his Epistulae Morales, associates audacia to the vice of recklessness, but similar to Cicero, denotes that audacia is a corporal virtue, stating, “Does not boldness (audacia) drive us ahead? Bravery (fortitudo) spur us on, and give us momentum?”11

So what is this contentious wellspring of courage, boldness and valor that drives us ahead, and yet—in the wrong setting—can be impudent and reckless? It’s the irascible passion that Aquinas derides, what Aristotle terms Thymos (θυμός), or a spiritedness, which he determines is, “an agency to be used by the rational will within due limits.” (Rickaby, pg. 3)

The soul in its own rational nature (for our present purpose we fuse together the two terms psyche and nous, distinguished by Aristotle, into one — the soul) is simple: man is compound, and, being conflictingly compounded, he has to drive a pair of steeds in his body, one ignoble — the concupiscences — the other relatively noble — the spiritual element, in which is "go", "dash", "onslaught", "pluck", "endurance". Upon the latter element is based fortitude, but the animal spirit needs to be taken up and guided by the rational soul in order to become the virtue. It is in the breast that ho thymos, to thymoeides (courage, passion) dwells, midway between reason in the head and concupiscence in the abdomen.

—Rickaby; The Catholic Encyclopedia

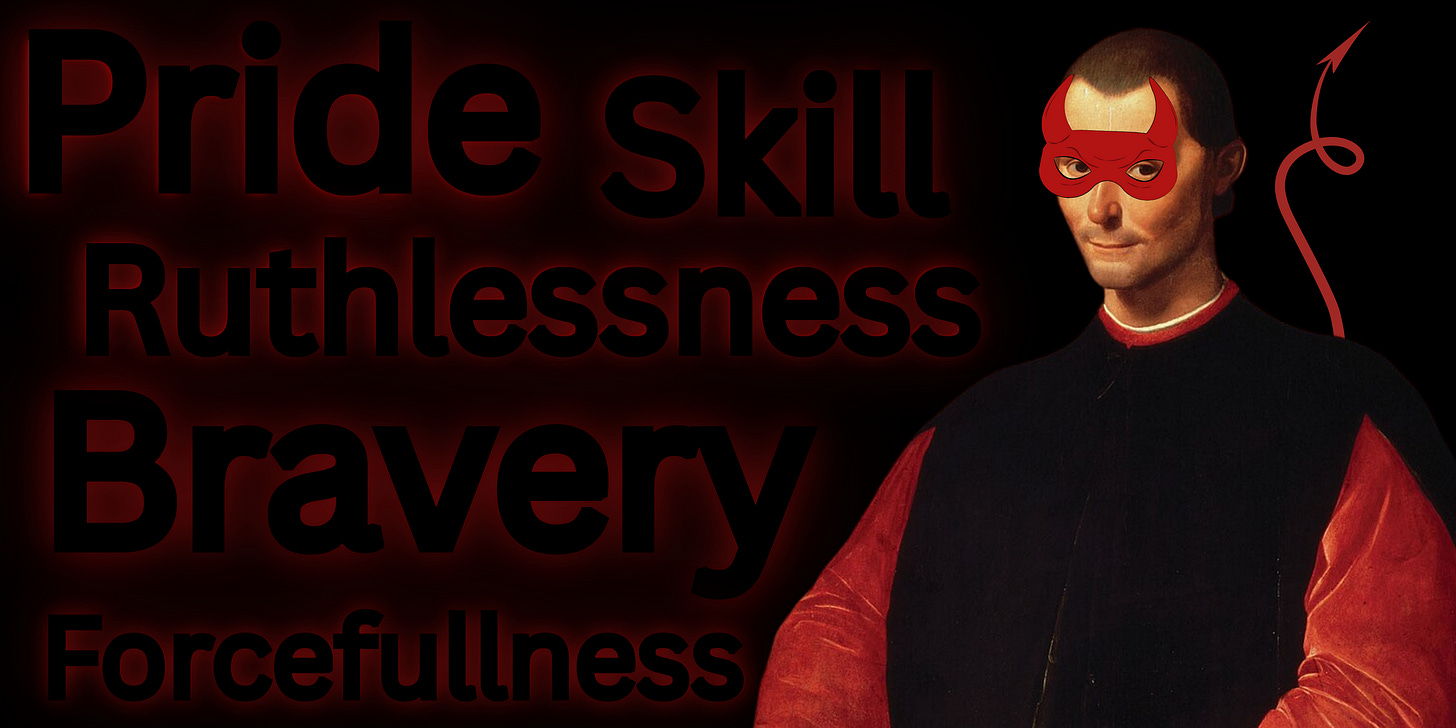

The contentious political theorist, Niccolò Machiavelli, postulated his own set of martial and stately virtues, notably, “pride, bravery, skill, forcefulness, and an ability to harness ruthlessness when necessary.” (Virtú; Wikipedia) To the keen observer, the lack of justice, prudence, and temperance will stand out, especially in regards to the conduct of the state. The virtue of prudence, which we will discuss later in this article, was of particular interest to Machiavelli. He believed that prudence was lashed to the mean of morality, thus inhibiting the effective rule of a prospective prince. Instead, he postulated that the virtue should be enriched with a spiritedness, he called animo—which, as Mansfield notes, is Aristotle’s thymos.

To act on prudence one must have animo, an animated spirit. Animo is Machiavelli's version of the Greek thymos, the spirit of self-defense that paradoxically can lead to the risking of one's life for the sake of saving one's life. Cool reason will not suffice to carry out a prudent action on its own but needs the-rationally dubious-assistance of a fiery temperament. That temperament ex- acts a price of unreason that Machiavelli is willing to pay. Unlike his successors he does not use the concept of necessity to dampen conflict and bring peace, because he sees the connection between animo and virtue. Hobbes, with his right of self-preservation, cannot show why a soldier in the field should not run from danger. But for Machiavelli, animo is the raw material of virtue. Animo is brutish and uncultivated; it is subhuman and below manliness. If those who look for Machiavelli's virtue in manliness would pay attention to animo, they could preserve the spiritedness they rightly discern in Machiavelli's recommendations.

—Mansfield, pg. 40

Because Machiavelli specifically targets prudence as the governor of temperament, we can effectively see it as the same quality as the martial virtue of Audacity. It's an extreme position, beyond the rational limits of Aristotle, and in direct contention with the disparity of irascible passion purported by Aquinas. The question we have to answer is, why? And is this of any relevance?

As a theorist and generally sub-par historian, Machiavelli observed that it was an overabundance of cautiousness and a lack of killer-instinct that generally inhibited the effective rule of a prince. Furthermore, it was an acute deficiency of animo that made the Condottiere of the early to mid-15th century ineffective and listless on the battlefield. His prescribed virtú were an attempt to correct this course. This is precisely where the theologians, and philosophers come into contention with the reality of martial necessity. Where the need for Germanic and Celtic pagan ideals of boldness came to rule the warrior ethic of Chivalry, as the pagans—especially the northern pagan traditions—lauded audacity or boldness {the extremes of courage} as an essential trait of a well-adjusted man within their tribe; their warrior class. It was necessary for the function of ‘their’ polis.

So how does this animo translate to fencing?

“The proper feeling for this art is one that knows no humility, caring displays, nor mercy, niceties, inanity or laziness. If you were to keep any of these alive in you and persevered in niceties and loving meekness, you would lose honor and gain shame to a high degree. So, you must first rid yourself of fearful thoughts and actions, or other traces of what produces anxiety. These thoughts and action do not contain the virtues required in a manly and formidable fight, since you become a slave to these feelings, you are like the dew in the sun or like a fable with no moral.”

“All should regard this art as not needing the feelings I have just mentioned, which is quite the opposite from the virtues that normally embellish a person as precious stones are mounted on unmixed gold. Likewise, in fencing, you must be virgin-pure from any hint or whiff of fear, and of any negative mental image. The true virtue of this art consists in being intimidating, and in possessing such ferocity as to appear to be on fire, with fierceness and absolute mercilessness in your countenance. Every slightest motion you make must exude a craving for delivering cruel blows; when you approach the opponent with such fierceness, you will completely wipe out his self-possession.”

“Move in such a way as to give him the impression that every gesture from you carries the potential for inflicting a crippling wound. Make your attacks so cruel and violent that even the slightest blow is enough to fill the opponent with dread. In this art, you need to act and have the countenance of the cruelest of lions or the angriest of bears. Actually it wouldn't be a bad thing if you could make yourself look like a great devil and act like you wanted to whisk away his soul.”

So much is this ingenious art of defense based upon four principal factors more important than any others: courage, cunning, strength and skill; and he that will adopt these qualities will never have shame, because should you have adopted these qualities and encounter an opponent who is lacking one, so shall you never need to worry of being able to have victory; and moreover should you encounter one who does possess all of these virtues, he will not last long in a fight, so long as you surpass him in one or more of these virtues; and so one who will possess these said qualities will fill his art with glory and honor, because in the discipline of these martial arts they demonstrate the erudition and intelligence which are the principles to the adornment that are the self-evident fruits of the workings of those principles, those principles being courage, cunning, strength and skill; and from these come the roots which give the delightful fruits; the glory of courage is to have cunning and wanting to enrich this cunning with a crown of pure gold, we will accompany it with a fortress; and wanting to embellish this fortress and give to it the fountain of life we will accompany it with a faithful escort of intelligent skill of such art that its ornament is salvation.

—Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 12

This exposition on the arts true recourse would probably make Saint Thomas Aquinas blush, but our friends Aristotle and Machiavelli would see it a bit differently. Many a master has wrestled with the notion of the irascible passion—the battle rage that inspires acts of great heroism—and tried to harness its utility through an application of virtue. In the anonymous author’s prologue we see it outlined beautifully. The absolute necessity of virtuous undertaking to enliven the skill and excellence of a martial practitioner, bookended with the harsh reality of its ultimate execution—the irascible passion in harmony with virtue.

While the anonymous author is quite direct in the allusion of dominance—Every slightest motion you make must exude a craving for delivering cruel blows; when you approach the opponent with such fierceness, you will completely wipe out his self-possession—he’s not alone. According to Jess Finley, the KdF tradition is full of hunting analogies, even the word leger; used for the four principle guards of the tradition, means lair, and was co-opted as a type of hunt in which one would drive an animal from its den—denoting an offensive bias of those guard positions. Similarly, the verb cacciare used by Marozzo to describe his seminal thrust in many of his abatimenti and combattare, means to drive out, to hunt, or to chase. This neatly coincides with the notion that the refinement of martial practice was not performed in the salle alone, but in the hunt—the act of driving fauna into the inescapable clutches of death.

It’s worth restating, that this is not to say that the extreme of the animo/thymos/audacia should rule a martial practitioner alone, or act as an underlying motivation as Machiavelli prescribes. As Giovanni Legnano noted, “Audacity, however, differs from fear ; for audacity is a feeling of the irascible appetite, inclining us to attack what is terrible…But either may be a good or a bad act.” Plato addresses this concern and the proper role and demeanor of a soldier in the Republic, as Boccadiferro notes in dialogue with Rodomonte, in book one of Viggiani’s, lo Schermo:

BOC: Plato explained this well in his book The Republic. He said that a true soldier needs three things: anger to fight the enemy; gentleness for friends and fellow soldiers; and philosophy, that is widsom, to tell the difference between right and wrong, friend and enemy, and what helps or harms.

He even compared a good soldier to a smart dog. A good dog is gentle with its family and friends, but fierce with strangers. It knows who belongs and who doesn’t. This is true even if it has never been hurt by a stranger or helped by a family member. It just knows, by nature and instinct—and that’s the kind of balance a soldier should have too.

RODO: So now, as a joke, you want to compare a great captain to a dog. That might be fine in another setting, but here it is insulting – it seems like you are deliberately insulting the captain.

BOC: Not at all. This idea actually comes from the great philosopher Plato. And it shouldn’t seem strange, because many human strengths and weaknesses can be compared to animals. And the word “dog” shouldn’t be seen as an insult. Among all the irrational animals that can’t speak, the dog is one of the few that is suitable for training and that also possesses discipline.

RODO: But it sounds to me like Your Excellency is contradicting yourself. Earlier you said a soldier shouldn’t act out of anger. Now you’re quoting Plato, who says a good warrior should have anger.

BOC: I don’t think I’ve contradicted myself, my lord. Having anger doesn’t mean being wild or out of control. Plato meant a kind of strong spirit or courage, not a blind rage. Anger should be balanced and stay within reason. When he speaks of “anger, gentleness, and philosophy” we should understand heart, wisdom and a controlled anger. That matches the hand, eye, and foot we talked about earlier.

This is the thymos governed rationally. To the anonymous author the vices of audacity are humility, caring displays, mercy, niceties, inanity or laziness, which stand to undermine the martial virtues of courage (Fortitudo), cunning (Prudence), strength (Fortezza) and skill (Celerity). The reason he lists these qualities, is he believes these are the origins of fear and anxiety, the antithesis of Audacity, which is bold and fearless.

“None carries a bolder heart than me, the lion,

But to everyone I make an invitation to battle.”

— (Fiore; Chidester, Wiktenauer)

Now, how do we put this together? How do we utilize the virtues to corral and rule the spiritedness of a bold and audacious heart? Where do we find the rationality to tame the animo?

This spiritedness finds it’s wellspring in the form of physical and moral fortitude, as illustrated by Contamine, “Force gives both fearlessness and bravery in war.” Fearlessness being the defining characteristic of boldness; which is, “fearless{ness} before danger” according to Websters Dictionary. We can see an analogous expression in the Davidic ethic as well, Proverbs 28:1 says, "The wicked flee when no one pursues, but the righteous are as bold as lions"—a statement that reads like Plato’s definition of fortitude imbued with the emblematic boldness of audacity.

This draws an interesting correlation between the ‘grounded’ fortitude at the base, and the audacity or boldness to go forward and attack with the hands; the positional qualities illustrated in Fiore’s segno of the seven swords. Greg Mele asserts that the elemental perception of the Medieval mind is paramount to the polar placement of Fiore's virtues. That is, fortitude is given unto the earth and is the bedrock and strength of the Vitruvian figure, the virtue of celerity is on the right denoting water; like the speed of a rushing river (pour one out for Muzio), prudence is above—denoting air—akin to the ethereal wisdom of the eternal soul, and audacia is placed on the left, which denotes the fire and passion of the heart, and an inescapable association with the holy land.

Symbolically, the elephant with the castle upon its back was also a symbol of the holy land—more specifically for crusaders and pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem—often depicted in crusader maps or representing the Jewish diaspora living in Italy, and perhaps stands to reason that the symbolic representation of fortitude is the path or source of the boldness which comes from the heart—that is a passion born from and measured by the tempered mean of courage. Following this line of progression, it’s symbolic representation as a lion, has meaning beyond the characteristic boldness, courage or bravery we often associate with the animal. The lion was the symbol of the Tribe of Judah, and Christ himself is deemed the Lion of Judah in the book of Revelation12, fulfilling the prophecy of Jacob in the book of Genesis.13 Thus the lion is the holy land, and the elephant the means with which to get there.

To expound upon this further and relate the virtue to the body and fencing specifically, Viggiani determines that the nature of a person's heart is made evident by how they use their hands:

BOC: Let me explain. The hand shows what kind of spirit or heart a person has, depending on how it moves—quickly or carefully. The heart controls the hand, whether it’s used to strike wisely or to defend bravely.

—Viggiani, Book I; Fratus

Without—God forbid—wading too far into the mire of George Silver’s true times, the tempo of the hand is faster than the feet. Thus the the hands have a greater opportunity to take risk, be bold, and recover than an overcommitment of the feet. Audacity is best served as a ferocious swipe of a lions paw, or the sudden lash of a coiled viper. This is our agreddi. Yet, even these zoomorphic exemplars—when observed in nature—are heavily rooted a in coiled base or a powerful well grounded body. Our sustinere.

We could define this union of fortitude and audacity; sustinere and agreddi, as valor.

“Fortuitous outcomes are directly proportional to fortune and inversely proportional to art. A fortuitous outcome is more likely in a battle than in a duel. There is therefore more art in the latter than in the former. The more the art, the more the excellence. Therefore, since it is more excellent to fight a duel one against one than to fight a battle (countless against countless), it takes more valor to graduate from a battle to the duel than the other way around.”

Giovanni Battista Pigna, Il Duello, 1560; Leoni

Valor. A word that Marriam-Webster defines as, “Middle English valour "worth, worthiness, bravery," borrowed from Anglo-French valor, valur, inherited or borrowed from early Medieval Latin valor, from Latin val- (stem of validus "in good health, robust, having legal authority," valēre "to be well, have strength(.)” It’s a word that also shares the same PIE root "*wal-" with the word wield; as in to wield a blade, and means to be strong, to govern.14 Perhaps it's symbolic that the natural disposition of untrained person with a sword is to attack recklessly or violently (aggredi/audacia) like a peasant or a villano, but the art of fencing—the schermo—is rationally conveyed as defense (sustinere/fortitude) and calculated methodical forms of attack.

Other sources define Valor as, “boldness or determination in facing great danger, especially in battle; heroic courage; bravery..” It’s a word that encompasses it’s etymological ancestor of strength (fortezza), and the virtuous expressions of courage (fortitudo) and boldness (audacia). A satisfaction of ἀραρίσκω/ararískō, to join, to fasten, to equip, to fit, to make pleasing, to make suitable. Thus it is the prudence of the mind and the courage—resolute defense—of our feet, that allows us to act with the irascable passion and animo of the heart.

“If you cultivate or follow the highly-ingenious art of fence (or art of arms) you must make sure that as you acquire the aforementioned virtues, you are totally devoid of fear. It is quite obvious that the fearful will never win a battle or be crowned in victorious triumph. The roots of trees that produce unjust, poisonous branches and fruits never yield good refreshment.”

—Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 12

Prudence:

In a modern context prudence, is often misconstrued as meekness, narrow mindedness or being risk averse. These are mischaracterizations aligned more with the extreme than the mean of prudence—though Machiavelli would certainly approve of this assesment. C.S. Lewis, in Mere Christianity, summarizes prudence simply as common sense or practical wisdom, deriding the notion that the virtue is tied to innocence when Christ himself compels his followers to be as shrewd as vipers.

In conjunction with this, Proverbs 22:3 states, “A prudent person foresees danger and takes precautions. The simpleton goes blindly on and suffers the consequences.” This notion of wisdom and awareness, being able to foresee rather than to proceed blindly, is evident in Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s proclamation that Prudence is the chief virtue of a soldier, and draws a nice comparison to our sustinere definition of fortitudo, and the unhinged recklessness of the animo or aggredi when not guided by prudentia or its fortuitous precursor:

Now, those who defend themselves against their enemies, simultaneously beating aside their insolence instead with art and mastery, are properly said to be protecting themselves when it comes to pass that they utterly save themselves and the republic.

And in this action prudence holds the chief place. While on the contrary, whoever faces his enemy’s fury without art or mastery, always ending up rashly overcome, finds himself not defended, but rather derided for it. Accordingly, if you do not grant prudence a place of honor, rather holding it in no esteem, then this art, which is founded and based on prudence, will usually be seen to hold little value for you.

—Giovanni dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 5

The martial virtue of prudence is more than just wisdom, born from experience and knowledge, it’s an acuity—a sense of awareness—and an ability to see and foresee what your opponent plans to do. As Fiore says, in the Pisani Dossi, “No creature sees better than me, the Lynx. And I always set things in order with compass and measure.” (Fiore; Chidester, Wiktenauer) and the Latin, Morgan copy states, “Everything born under the sky will be discerned with [my] eyes; I, the lynx, I conquer [by] measurement whatever it pleases [me] to attempt.”

Prudence is often linked with the sense of sight or cognition; as in Fiore ‘no creature sees better than I the Lynx’, and the Psalms; ‘A prudent person foresees danger’, ‘the simpleton goes blindly’. Symbolically, the beastial myth of the Lynx was believed to have two magical powers: it’s urine could form solid amber (ligurius), and it had a sort-of x-ray vision and a sense of clairvoyance. That is, it could see the unseen, or look through an object to see what was underneath—often to reveal a hidden truth, as well as the power to look into the future.15 From a fencing perspective, that is similar to the characteristic of foresight imbued by the virtue of prudence, eg. when a fencer can see the guard or placement of their opponent and perceive what will happen next.

And so, we have taught and given the knowledge of the gallant guards that pertain to this ingenious art of defense, for there is no thing in this art that you need to understand more readily. This way when you find yourself against an enemy, you can immediately identify how the swords are placed, for the attacks one may make with the sword are infinite and innumerable, and so too are the ways in which the swords may be found; yet from one guard or another, not all attacks will be suitable, and by being shrewd, and also being illuminated with the knowledge of your enemy's placement, you will make effective attacks, in the correct tempo, using your sword and your body; and by making attacks in this manner you will remain secure from harm.

Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 59

Setting aside the symbolic and mystical for a temporal perspective, sight is one of the two primary senses that informs fencing—the other being touch or feel. Following this narrative of acuity, Viggiani notes:

“The eye watches and helps the mind make decisions more than any other sense. Sight is the most important sense for understanding and reacting—more useful than hearing & smell, and certainly of far greater importance than taste or touch. We trust what we see the most. So when the eye sees an enemy’s attack, it tells the mind how to respond quickly and wisely. Or when the eye spots an opening, it helps find the best way to strike.”

—Viggiani, Book I; Fratus

Alas, without experience and wisdom—that sense of foresight—and our virtues of audacity and fortitude, the eyes can be a weakness. For many of the authors the heart and the eyes work in tandem with one another and are inseparable:

“(B)ecause my heart and my eyes are never focused anywhere other than upon taking away your dagger quickly and without delay.” (Fiore, 5th Master of the Dagger; Chidester, Wiktenauer)

“Delivering attacks from the waist up causes more danger in the opponent than doing so from the waist down, since the eyes (and consequently the heart) of the not-so-brave are easily conquered by such flashes.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 115)

The dangers that you see and perceive will test the courage of your heart. Thus, the eyes and the heart must be of one accord. Therefore, it is through our knowledge and wisdom that we can be bold and audacious under duress or in pursuit.

…(T)empo needs agility and skill; and this agility and skill requires courage, and this courage must be accompanied by judgment, and this judgment one cannot have without experience, the mother of all education, and this education we will give you.

—Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 60

To further highlight the interconnectedness of the virtues, prudence is acquired through fortitude—by enduring the rigors of training, toil, and study. As the anonymous author details:

“I'll say that if you aim for the honor of expertise in this art, you need to prepare yourself in the way I describe. First you need to adopt a high degree of attention to detail and perseverance. Attention to detail and perseverance must come with much toil. Toil must come with a good deal of patience. Patience must come with love of the art, which cannot materialize without understanding. Understanding requires grasping the reason behind the art, and these require support which in turn requires intellect and prudence. Prudence must come with knowledge. Once you attain this prudence and knowledge, your judgment will be that of an expert.”

Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 12

Knowledge, perception and experience are the roots from which Prudence grows, but the fertile soil in which it's sown must be enriched with the courage to endure and audacity to act on what you see and perceive, and it’s through this cycle of growth that a new virtue will emerge.

Celerity:

Just as perseverance in continuing this most refined art of fencing shall quickly instill agility and skill, and so does the virtù in them shine brightly. And the greater is one's devotion and perseverance, the greater shall burn the light of their perfection.

Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 74

Celerity is speed, but speed is inherently the biproduct of two factors: skill and agility. As the anonymous author illustrated in the quote above, refinement through constance and perseverance breeds both attributes. Just as there were sub-virtues and sub-vices of the aforementioned martial virtues, we can assign similar extremes to Celerity, and define the mean. If skill and agility are the desired traits: the deficiency of agility could be clumsiness and the extreme could be avoidance; ie. continuous movement without progress toward an end, while the extreme of skill could be form without function and it's deficiency could simply be a deficiency of form.

I am the Tiger, and I am so quick to run and turn, that even the thunderbolt from heaven cannot catch me.

—Chidester; Wiktenauer

Speed that lacks form is inherently useless, ie. performing sword actions as quickly as possible without the requisite skill to put the point or edge on target serves little purpose in the ultimate objective of a fencing bout. Similarly, an over emphasis on form can create a rigidity and lack of flow that renders one vulnerable or even slow. Agility or nimbleness, is also paramount; a lack of of agility, or clumsiness, leaves one vulnerable when they commit to a strike through over-extending or over-committing and an excessive emphasis on control can leave many opportunities to strike orphaned for the sake of that perfect opportunity or set-up.

The symbolic representation of the tiger in Fiore is quite interesting. According to the contemporary mythological representations of the tiger, the fearsome animal could be warded off with a mirror. Contextually, this could be a warning not to match the speed of an opponent that is beyond your skill and ability. While a fascinating alternative, suggested by Harry Hupman, is that the best way to beat speed and aggression is through deception, as the reflection of the tiger in the mirror will trigger the tigress’ deep maternal instinct—confusing it's reflection for a cub—which can buy you just enough time to get away, or land that fatal blow.

As you are at the strette of the half sword with your opponent, and you are to be the agent, you need to be very quick with your hands; if you are slow and lazy, you will always end up being the patient.

—Antonio Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 153

Among the Bolognese authors it should come as no surprise that the virtue of speed is embodied through tempo—time. The sub-virtue—skill—of which is knowing when and how to make contra, half and full tempo actions. This is born from experience and practice:

Now he that that will work in this art will be most quick and vigilant and mindful of the great secrets of the execution of the discipline, and will be secure in his operation and know well what his enemy will be able to do, and know all those things he may try in his tempo. For once you understand the tempi you will find confirmation of their virtue as you use them; and from there you need have little fear of obtaining good results. As he on the day of battle who is thoughtful and deliberate and proceeds with in ingenious artfulness in order to preserve his life and honor, he shall never need to fear; rather he will make himself happy in its workings for the manliness of his resounding fame which stands above all other things because the virtue of the honored lifts itself over all other glories and so is wonderful in the faith of the fruits of the ingenious art of defense.

—Anonimo Bolognese

Skill, agility and deception are all qualities paramount to execution of celerity.

Conclusion:

Because many components are looked for in a good fencer, and far more so in one who conducts himself to combat, such as: reason, boldness, strength, dexterity, knowledge, judgment, and experience.

—Giovanni dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 6

The Virtues are meant to represent the pillars of ones practice, a foundation upon which you can build your ideal form. Prudence, fortitude, celerity, and audacity are almost universally discussed from the Medieval texts of Fiore dei Liberi to the later Bolognese authors like Giovanni dall’Agocchie.

The virtues must harmonize with one another. Fortitude, audacity, and celerity are listless with out the keen awareness of prudence. While prudence, celerity, and audacity must have their foundation in the enduring courage of fortitude. Similarly, one may be fortuitous, prudent and audacious, but find themselves overwhelmed if their skill and agility have not come to render celerity. And what are prudence, fortitude, and celerity without the boldness to act on what one sees, endures, or skillfully attains.

There is a cyclical nature to the relation of the virtues. A perpetual revolution of conduct and deficiency that illuminates the incomparable reality of success and avenues for self improvement in the danse macabre.

So, what are the virtues in the end? They are a roadmap to mastery. A mastery of mindset and person—beyond the plays, devices, and glosses of the various masters. A refinement of the ultimate weapon. You.

Appendix:

List of Virtues by Author:

Fiore dei Liberi:16

Prudence

Celerity

Fortitude

Audacity

MS. 3227a:17

Braveness

Celerity

Cautiousness

Cunning

Prudence

Paulus Kal:18

Eyes like a hawk

Heart of a Lion

Feet of a Hind (Deer)

Filippo Vadi:19

Prudence

Providence/Foresight

Firmness

Quickness

Measure

Antonio Manciolino:

Gravi

Apostati

Gracefulness

Quickness

Strength

Fortitude

Anonimo Bolognese:

Courage

Cunning

Strength

Agility

Attention to Detail

Perseverance

Prudence

Knowledge

Judgement

Angelo Viggiani:

Discipline

Courage

Knowledge

Giovanni Legnano:

KdF Virtues:

Works Cited:

McAleer, Sean. Plato's Republic: An Introduction. United Kingdom, Open Book Publishers, 2020.

Floyd, Shawn. Aquinas: Moral Philosophy | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (n.d.). https://iep.utm.edu/thomasaquinas-moral-philosophy/

The Five Knightly Virtues in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. (2020, Apr 13). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-five-knightly-virtues-in-sir-gawain-and-the-green-knight/

Contamine, Philippe. La guerra nel Medioevo. Italy, Il Mulino, 2014.

Irwin, Terence. Aristotle; Nicomachean Ethics, 2nd Edition. Hackett Publishing Co., Indianapolis, 1999. Print.

Mansfield, Harvey C.. Machiavelli's Virtue. Germany, University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Rickaby, John. "Fortitude." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06147a.htm>.

Kleinau, Jens P. Talhoffer, V. a. P. B. (2017, February 15). The virtues of fighting – The Liechtenauer manuscript GMN 3227a. Hans Talhoffer. https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2011/07/12/the-virtues-of-fighting-the-liechtenauer-manuscript-gmn-3227a/

Paulus Kal ~ Wiktenauer, the world’s largest library of HEMA books and manuscripts ~ Insquequo omnes gratuiti fiant. (n.d.). https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Paulus_Kal

Fiore de’i Liberi ~ Wiktenauer, the world’s largest library of HEMA books and manuscripts ~ Insquequo omnes gratuiti fiant. (n.d.). https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Fiore_de%27i_Liberi

appostare - Wiktionary, the free dictionary. (n.d.). Wiktionary. https://en.m.wiktionary.org/wiki/appostare

Wikipedia contributors. (2025, April 10). Virtù. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virt%C3%B9#:~:text=Virt%C3%B9%20is%20a%20concept%20theorized,came%20to%20mean%20an%20object

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, November 1). Lynx (mythology). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lynx_(mythology)

Hursthouse, Rosalind and Glen Pettigrove, "Virtue Ethics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/ethics-virtue/>.

Smith, J. Warren. Christian Grace and Pagan Virtue: The Theological Foundation of Ambrose's Ethics. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Bragova, Arina. Caliniuc, S. (2018, December 19). Cicero on vices. Studia Antiqua Et Archaeologica. http://saa.uaic.ro/cicero-on-vices/

Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales: With an English Translation. United Kingdom, W. Heinemann, 1917.

Sfetcu, Nicolae (2022). "Plato: The Republic", in Telework, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.21273.90723, URL = https://www.telework.ro/en/plato-the-republic/

Lt. Col. Vineyard, James. Army University Press. (n.d.). Cardinal virtues as warrior virtues. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/Online-Exclusive/2025-OLE/Cardinal-Virtues/

Catholic Encyclopedia: Fortitude

Manliness is etymologically what is meant by the Latin word virtus and by the Greek andreia, with which we may compare arete (virtue), aristos (best), and aner (man). Mas (male) stands to Mars, the god of war, as arsen (male) to the corresponding Greek deity Ares.

Sfetcu, pg. 1

The Republic was written approximately between 380 and 370 BC. The title Republic is derived from Latin, being attributed to Cicero, who called the book De re publica (About public affairs), or even as De republica, thus creating confusion as to its true meaning.

Smith, Synopsis

Ambrose of Milan (340-397) was the first Christian bishop to write a systematic account of Christian ethics, in the treatise De Officiis, variously translated as "on duties" or "on responsibilities."

Smith, Pg. XII

Ambrose's ethics are largely derived from pagan philosophical sources , then they cannot be viewed as an outgrowth of his theology.

Floyd; 1. Metaethics

Aquinas’s metaethical views are indebted to the writings of several Christian thinkers, particularly Augustine’s Confessions, Boethius’s De hebdomadibus, and perhaps Anselm’s Monologium. Due to the constraints of space, the present section will only consider Augustine’s influence on Aquinas’s views.

The Five Knightly Virtues of Gawain.

In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain, the youngest knight, departs on a perilous adventure, where he must maintain the “five knightly virtues” (Champion, 421). These virtues are: fellowship, purity, courtesy, pity, and franchise (Champion, 421). On New Year’s Day in King Arthur’s court, a knight dressed in green arrives and proposes a challenge. Gawain accepts this challenge, and then he must leave several months later to complete it.

Rickaby, John. "Fortitude."

Although Aristotle makes animal courage only the basis of fortitude — the will is courageous, but the animal spirit co-operates (ho de thymos synergei) — he has not a similar contempt for the body, and speaks more honourably of courage when it has for its prime object the conquest of bodily fear before the face of death in battle. Aristotle likes to narrow the scope of his virtues as Plato likes to enlarge his scope. He will not with his predecessor (Lackes, 191, D, E) extend fortitude to cover all the firmness or stability which is needful for every virtue, consequently Kant was able to say: "Virtue is the moral strength of the will in obeying the dictates of duty" (Anthropol., sect. 10, a). The Platonic Socrates took another limited view when he said that courage was the episteme ton deinon kai me (Laches, 199); hence he inferred that it could be taught. Given that in themselves a man prefers virtue to vice, then we may say that for him every act of vice is a failure of fortitude. Aristotle would have admitted this too; nevertheless he chose his definition: "Fortitude is the virtue of the man who, being confronted with a noble occasion of encountering the danger of death, meets it fearlessly" (Eth. Nic., III, 6). Such a spirit has to be formed as a habit upon data more or less favourable; and therein it resembles other virtues of the moral kind. Aristotle would have controverted Kant's description of moral stability in all virtue as not being a quality cultivatable into a habit: "Virtue is the moral strength of the will in obeying the dictates of duty, never developing into a custom but always springing freshly and directly from the mind" (Anthropol., I, 10, a). Not every sort of danger to life satisfies Aristotle's condition for true fortitude: there must be present some noble display of prowess — alke kai kalon. He may not quite positively exclude the passive endurance of martyrdom, but St. Thomas seems to be silently protesting against such an exclusion when he maintains that courage is rather in endurance than in onset.

Rickaby

Aristotle says that mercenaries, who have not a high appreciation of the value of their own lives, may very well expose their lives with more readiness than could be found in the virtuous man who understands the worth of his own life, and who regards death as the peras — the end of his own individual existence (phoberotaton d' ho thanatos peras gar). Some have admired Russian nihilists going to certain death with no hope for themselves, here or hereafter, but with a hope for future generations of Russians. It is in the hope for the end that Aristotle places the stimulus for the brave act which of itself brings pain. Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ("It is sweet and noble to die for one's native land" — Horace, Odes, III, ii, 13): the nobility is in the act, the sweetness chiefly in the anticipated consequences, excepting so far as there is a strongly felt nobility (Aristotle, Eth. Nic., III, 5-9) in the self-sacrifice.

Reich; Manciolino, Wiktenauer.

aSsai piu che li nostri schermitori assalti sono felici quelli nelle uergate carte, che li scarmigliati satiri alle uenatrici nimphe fanno. Percio, che cotali si dilicata alli scrittori paranno la materia, che da se le soaui parole si compongono sotto uno continouo & dolciato stilo, mentre le lanose membra de gli semicapri iddii, olle cornute loro fronti, o gli lasciui mouimenti, olli loro sempli ci & rusticani aguati componer si parecchiano, non scriuendo, ma depinte mostrando le affannate dee nel lungo corso, alcune leuantisi gli purpurei panni sopra il candido Ginocchio con le bionde ciocche de gli ricaduti capelli sopra le morbide spalle, ouero con quelli sparti & da soaue orizzamento uentilati, altre git- [30v] tatesi nelli chiarissimi & correnti fiumi, cosi istimando gli insidiatori delle loro uerginitati a Diana consegrate, fuggire, & alcune da grande lassezza uinte star dietro alle folte macchie nascose, tali nelli uisi quali le matutine rose nel apparir del sole ueggiamo souente & quelle per uitreati sudori giocciolanti ansiando con le sottili dita delle mani bianchissime render asciutti. Ma non essendo il soggetto a me di ueruna cotale leggiadria proposto, …appo gli intendenti lettori meritarono perdono percio, che non recando altro seco, che mandritti, riuersi, falsi, punte & simili uoci lequali (uogliendo essere nella arte intenduto) non possono in altri nomi cangiarsi, come fara la significatione del passare, che di continuo nella scriuente penna mi corre, mentre cosi spesse fiate auiene dire, chel giocatore passi con il manco, o con il destro pie de, conciosiacosa che dir possi, passare, uarcare, ualicare, scorrere, scorgere, guidare, o condurre il piede, & doue dice destro, dicemo talhora in uece soa dritto, o forte, o ualido, perche ha l’huomo piu fortezza nelle destre parti, che nelle sinistre naturalmente, & parimente, quando sinistro, quando manco, o debole, per fuggir il tedioso rincrescimento, non essendo cosa piu odiosa che la frequente repetitione di una medesima uoce, …

Wiktionary: appostare

appostàre (first-person singular present appòsto, first-person singular past historic appostài, past participle appostàto, auxiliary avére)

(transitive, military) to post, to station

Bragova, pg. 262

The next term is audacia. We have found 350 examples of its use in Cicero’s writings (including its derivatives audax and audacter/audaciter). The major part of the cases (more than a half) appears in his speeches, whereas a smaller part — in his correspondence (18 cases). It should be noted that the target group of the meanings of audacia, audax, audac(i)ter does not include their positive meanings connected with the semantic field of “courage” and “valour”91 as well as the use of audacius in the meaning of “more courageously” with the verbs deferre, dicere, disputare, expromere, exsultare, ingredi, inquam, scribere, transferre.92 Audacia and its derivatives, if Cicero assumes the negative meaning of “impudence” or “audacity”, are linked in the context with the words, which also have a negative connotation and denote defects or negative phenomena of social and political life. Audacia is often employed with the words denoting crime or atrocity: scelus (81 cases), crimen (36), facinus (29), nefarium (27), flagitium (14), maleficium (12), caedes (10), insidiae (10), parricidium (10), and the following punishment: supplicium (12 cases of use). Audacia is, of course, a vice for Cicero (vitium is used together with audacia 11 times).

Seneca; W. Heinemann, pg. 220-221

Non audacia inpellit? Non fortitudo inmittit et impetum dat?

Does not boldness drive us ahead? Bravery spur us on, and give us momentum?

Revelation 5: 5-6

And one of the elders said to me, “Weep no more; behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, has conquered, so that he can open the scroll and its seven seals.”

6) And between the throne and the four living creatures and among the elders I saw a Lamb standing, as though it had been slain, with seven horns and with seven eyes, which are the seven spirits of God sent out into all the earth.

Genesis 49: 8-12

8) “Judah, your brothers shall praise you;

your hand shall be on the neck of your enemies;

your father’s sons shall bow down before you.

9) Judah is a lion’s cub;

from the prey, my son, you have gone up.

He stooped down; he crouched as a lion

and as a lioness; who dares rouse him?

10) The scepter shall not depart from Judah,

nor the ruler’s staff from between his feet,

until tribute comes to him;

and to him shall be the obedience of the peoples.

11) Binding his foal to the vine

and his donkey’s colt to the choice vine,

he has washed his garments in wine

and his vesture in the blood of grapes.

12) His eyes are darker than wine,

and his teeth whiter than milk.

Etymology Online:

*wal-

Proto-Indo-European root meaning "to be strong."

It might form all or part of: ambivalence; Arnold; avail; bivalent; convalesce; countervail; Donald; equivalent; evaluation; Gerald; Harold; invalid (adj.1) "not strong, infirm;" invalid (adj.2) "of no legal force;" Isold; multivalent; polyvalent; prevalent; prevail; Reynold; Ronald; valediction; valence; Valerie; valetudinarian; valiance; valiant; valid; valor; value; Vladimir; Walter; wield.

It might also be the source of: Latin valere "be strong, be well, be worth;" Old Church Slavonic vlasti "to rule over;" Lithuanian valdyti "to have power;" Celtic *walos- "ruler," Old Irish flaith "dominion," Welsh gallu "to be able;" Old English wealdan "to rule," Old High German -walt, -wald "power" (in personal names), Old Norse valdr "ruler."

Wikipedia: Lynx (Mythology)

It is also believed to have supernatural eyesight, capable of seeing even through solid objects.[2] As a result, it often symbolizes the unravelling of hidden truths, and the psychic power of clairvoyance.[3]

Chidester, Fiore dei L

Chidester, Fiore dei Liberi; Wiktenauer

Prudence/Wisdom

No creature sees better than me, the Lynx.And I always set things in order with compass and measure.

No creature sees better than I the Lynx, and I proceed always with careful calculation.

Celerity/Speed

I, the tiger, am so swift to run and to wheelThat even the bolt from the sky cannot overtake me.

I am the Tiger, and I am so quick to run and turn, that even the thunderbolt from heaven cannot catch me.

Audacity/Daring

None carries a bolder heart than me, the lion,But to everyone I make an invitation to battle.

No one has a more courageous heart than I, the Lion, for I welcome all to meet me in battle.

Fortitude/Strength

I am the elephant and I carry a castle as cargo,And I do not kneel nor lose my footing.

I am the Elephant and I carry a castle in my care, and I neither fall to my knees nor lose my footing.

Kleinau, The “cardinal virtues” of the GMN 3227a.

The cardinal and knightly virtues had great influence on the educated, and from these well educated men and very few women we can learn the aspects of the virtues in the art of fighting. The first mentioning of the virtues in a martial arts treatise that still exists is the naming of “Kunheit / Rischeit / Vorsichtikeit / list / vnd klukheit” – “braveness, celerity, cautioness, cunning, and prudence” in the manuscript GMN 3227a currently dated to 1389 from an unknown author.

Paulus Kal; Wiktenauer:

I have eyes like a hawk, so you do not deceive me.

I have a heart like a lion, so I strive forward.

I have feet like a hind, so I can spring to and fro.