Fencers who deliver many blows without any measure or tempo may indeed reach the opponent with one of their attacks; but this will not redeem them of their bad form, being the fruit of chance rather than skill. Instead we call gravi & appostati those who seek to attack their opponent with tempo and elegance.

—Manciolino, Main Rules or Explanations on the Valiant Art of Arms ; Leoni, pg. 112

To deliver the attack or not to deliver the attack that is the question…

The art of Bolognese fencing has two predicates for safely executing an attack—provocation and riposte—and one objective, tempo. In order to immerse ourselves in the complexity of the underlying theory behind these two terms, we’ll first have to define a number of principles.

Tempo: Any movement of the sword or the body.1

Provocation: Cutting or thrusting to entice the opponent to depart their fixed guard.2

Advantage: You or the opponent are in advantage when3…

Disadvantage: You or the opponent are in disadvantage when…

You are not fixed in guard or have your point off-line in the presence of the opponent.

Are greater than a full step from your opponent; i.e., it would require a step and another motion of the feet to strike them.

Are performing a passing step to strike, or are lifting your sword to strike.

Invitation: Encouraging the opponent to attack you by creating the perception of disadvantage, or giving them the feeling they are in advantage.

Determining Your Role:

The onset of every fencing bout is a race to advantage. This can be simulated by the tiered circles of the segno, where the first fencer to attain the center circle holds advantage. Alas, as Camillo Palladini points out, one can't use a compass in disputes.7 So how do we determine our role in a four-dimensional environment?

One can cut this Gordian knot by defaulting to fencing with advantage; i.e., assuming the role of the defender foremost, and only attacking when the opponent also attempts to fence with advantage.8 By doing so, you won't find yourself attacking when you should be defending.

Moving forward I will categorize who is in advantage versus who is in disadvantage by simply calling the fencer in advantage the defender and the fencer in disadvantage the attacker. This is a gross oversimplification, but it will serve to simplify the roles of each fencer before we broaden the tactical scope.

The Role of the Attacker:

The role of the attacker can be defined rather simply, but the metaphysics that underlie the principle have the potential to become infinitely complex. As such I'm going give the simple definition first, along with the supporting text, followed by some general guidelines, and then we’ll dive into the principles that substantiate the metaphysics.

The role of the attacker is to continuously seek openings until they have achieved an advantageous (strong) position or have gained enough tempo that they can safely strike the person of the defender without recourse.

All of the Bolognese authors advise that at the onset of the fight your eyes should be fixed on your opponent’s sword hand. This advice comes with a number of advantages:

It allows you to perceive how your opponent wants to proceed9: i.e., guards on the left are defensive, guards on the right are offensive (offensiva, difensiva: Viggiani), point on-line can cut and thrust, point off-line can cut (perfecto; imperfecto: Viggiani).10

As the defender, you can use your knowledge of the opponent’s guard position to act quickly in accordance with the perceived attack.11

As the attacker, you will use the motion or lack of motion of your opponent’s sword hand as an indication as to how you should continue your attack.

As the attacker, you are generally advised to change guard frequently before entering measure to disguise the nature of your attack.12 Note that these guard changes should be performed out of measure, and only as a means to conceal your intended attack or as an invitation; this is defined as an embellishment.13

Once you have assumed the guard you wish to attack in, and you are within measure to threaten an opening, then you should begin your attack. A way to visualize available targets is to imagine the body of the opponent passing through a plane.

As the distance between you and your opponent narrows, more targets become available—which is true for both you and your opponent. This is where getting too close to an opponent who is in advantage becomes dangerous. On account of their stillness, they may act in the tempo of your approach, and deliver an attack. The closer you are to an advantaged fencer (the defender), the more openings you afford them to attack in tempo.

The first rule of attacking is that in the course of an attack which threatens a deep target, your sword must cover that of your opponent. That is, you must first be in a position of strength before you extend to strike, thereby weakening yourself.14

This strong position can be simply defined as a crossing. In Viggiani, this is outlined as advantage of guard, where your point is on-line and takes your opponent’s point off-line, though there is some complexity here that needs to be explained. In Altoni, this is simply referred to as a counter posture. In many of the later rapier fencing manuals, this is an obligare.

Putting the terminology aside for a moment, let's discuss how to achieve a crossing, and ensure our attacks attain a strong position. In order to do this effectively we must define some terms:

Mechanical advantage: You are in mechanical advantage when the strong of the sword (middle of the blade to the hilt) is on the weak of the opponent’s (middle of the blade to the point), or your edge is on your opponent’s flat.

Biomechanical advantage: Simply put, a fencer has biomechanical advantage when they use larger muscle groups (hips, back, shoulders) to overcome smaller muscle groups (hand, wrist, forearm).

Strengthening: Coming to a place of mechanical or biomechanical advantage—preferably both.

Weakening: Forming a weak guard to redirect the opponent’s sword away, or leaving a disadvantageous bind; cutting to a new opening or disengaging around the blade (sfalsata or cavazione)

This ingenious art of the sword consists above all of a half turn of the hand or a full turn of the hand; and this half turn or full turn of the hand needs to accompany a half blow or a full blow; and this half blow or full blow needs to be accompanied by a half turn of the body; and this half turn of the body needs to be accompanied by a half or full step; and this half or full step has a great need to be accompanied by a half or full tempo; and this half or full tempo needs agility and skill; and this agility and skill requires courage, and this courage must be accompanied by judgment, and this judgment one cannot have without experience, the mother of all education, and this education we will give you.

Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg 60.

The sword and the body must work together—always. This begins by connecting the sword hand to the arm, the arm to the shoulder, and the shoulders to the hips, which will make the back foot the rudder of your ship.15 This is a portion of what Manciolino calls this Gravi and Appostati: being well-composed in the right posture.

In a modern, sports science framework, we would call this chaining your actions; i.e., allowing different muscle groups to perform subsequent actions in a sequence.

An exercise that will help illustrate this follows: assume Coda Lunga Stretta, with the back heel raised and the back toe pointed toward the opponent, the profile of the hips facing toward the opponent. Then, without moving the sword hand or sword arm, only the heel of the back foot, transition between Coda Lunga Stretta and Porta di Ferro Stretta, by closing the back foot; i.e., bring the heel down so the feet form a 90° angle. The goal is to not move the sword hand at all, only the hips. (Note: your point will drift outside, and that's okay)

Now that you’re comfortable with that, try the same exercise with a partner. Have your partner stand in front of you with their sword in a low, but extended position toward you. Standing in Coda Lunga Stretta, transition to Porta di Ferro Stretta, only moving the back foot, and find your opponents sword. Congratulations, you have now found your opponent with both mechanical and biomechanical advantage. Better yet, you have initiated your attack with only one third of the available biomechanical chain.

"You need to make thrusts with control. Do not fling them forward as most men do. When you fling your thrust out then you will lack control, and it loses its virtù and becomes less certain. When your sword hand makes the thrust so that that the point remains always in control, you will be able to place it where you wish. If the need arises to pull it back or to put it into a guard so that you may stringere the opponent, you can do this most aptly and without discomfiture."

—Altoni, Monomachia; Fratus, pg. 24

The same exercise can be replicated with a cut. From Coda Lunga Stretta, raise the sword hand to a Guardia Alicorno or Beca Cesa position, and when you want to deliver your blow, close the back foot, and pull the pommel of you sword into your hip. With a half turn of the hand—palm out—accompanied by a turn of the foot; and thereby the hips, you'll pull back into a position to deliver another cut.

A way that this is often communicated is that an attack should target the opposite shoulder of the opponent; i.e., an attack originating from your right side should target your opponent’s right shoulder, and an attack originating from your left side should target the opponent’s left shoulder. This is advice that’s more appropriate for cuts than thrusts.

For a thrust, the point should directed past the outside of the shoulder over the opponent’s sword. Then, when a strong position is achieved—i.e., you’ve performed a half turn with the body by turning on the ball of the back foot—you can make a half turn of the hand from a palm-in to a palm-up position as you extend forwards with a half step and a hinge of the hips, bringing the lead shoulder forward.

Because this is Bolognese fencing16, the inverse of this; i.e., a find to the outside, will lead with the false edge of the sword. This can be done with structure, by simply raising the sword arm from Porta di Ferro to shoulder height (x axis), and allowing the hips to pull the sword across the y axis; utilizing a turn of the back foot to move the hips. The resulting guard position will be Guardia di Faccia; thus a falso that does not go past Guardia di Faccia. This can be visualized in the following way:

From this position, you can make a half turn of the hand, from a palm-up to a palm-down position, and your point will go from an off-line position, to an on-line position. It’s advised that you complete your motion to a position of strength (i.e., Guardia di Faccia) before making the mezza volta (half turn) of the hand.

From this position of strength, any extension of the sword away from the body with a thrust or a cut that intends to reach the opponent will be inherently weak—even with mechanical advantage. This is primarily due to the support of smaller muscle groups; i.e., moving down the chain. When the hands are close to the body, they're more connected to larger muscle groups in the back, shoulders, and core. When you extend the sword away, then the sword is supported by the shoulders, back (specifically the latissimus dorsi), and forearms. Due to your extension toward the person of the opponent, the opponent’s parry is more likely to involve larger muscle groups; i.e., they will be drawing their weapon in, and they will naturally have more biomechanical advantage.

Understanding this relationship will help you make a judicious decision about when to extend forward with an attack. If you are in a weak position, or haven't fully strengthened; i.e., completed your guard change, then you will be weakening from a place of neutrality or, worse, a position of weakness, which will allow the opponent to quickly overpower your attack.

Moving to place of strength at the outset of each attack will achieve two goals:

It will limit the opponent’s contratempo opportunities—ending neutral most of the time.

It will oblige the opponent to strengthen to neutralize the threat or weaken to attain a more advantageous position; wherein you may act in tempo.

The Branches of Trees are Rooted in if

If your opponent allows you to achieve a strong position in your initial find, then you can extend forward and attack the person of your opponent.

If they strengthen while you are weakening; i.e., extending to strike, then:

You can weaken further (with purpose, redirecting their strength away from you) and perform a mezza spada action.

You can weaken (cut to a new opening, sfalsata, etc.) and seek a new opening.

If your opponent starts to strengthen in the tempo of your find (your strengthening); you should weaken and seek a new opening, maintaining Frequens Motus, until a strong position is achieved, whereby you may extend forward and deliver an attack (weakening), thus starting the cycle over again.

If your opponent starts to weaken (sfalsata, cuts to a new line, wrenches, or attacks) in the tempo of your find (your strengthening); you should perform a beat on their sword or move to a strong position that intercepts or controls their weapon. In effect this is a role reversal, and you’ll have to work to regain control of the opponents weapon before proceeding with any attacks.

Frequens Motus, at its core, is continuously threatening new openings until the opponent makes a mistake, and allows you to gain advantage—a position of strength. But it's more than that. At the beginning, we established that all of the Bolognese authors advise watching the opponent’s sword hand. This continues past the onset, until you're close enough to your opponent where the left hand becomes the most prominent threat.

When you see that the opponent starts to parry (strengthen), you should seek a new opening in the tempo of their parry (weaken); as they move to parry this new attack (strengthen), you should seek the next opening in the tempo of their parry, until you can achieve a strong position.17 The objective here is moving before the opponent finishes their strengthening action. In theory, each subsequent attack will gain tempo until you're far enough ahead of your opponent that a strong position is achieved, and you may extend forward with your attack.

Marozzo describes this phenomenon like this:

“You should hold it to be a certain factor that no one who is attacked when raising out of a guard, or in falling from a guard, can perform any counter except for an instinctive response as if he knew nothing…But if perchance you were to attack him when he was neither rising nor falling, be advised that he could interrupt your intention with a variety of blows. So if you wish for honor, be attentive, and look to attack him as he rises or falls from his guard with his counters.”

—Marozzo, Capitolo 171; Swanger, pg. 256

Marozzo insinuates that you want to catch your opponent in the tempo of them raising to or lowering from their guard position, with the objective of not allowing the opponent to become fixed in a guard position. This is Frequens Motus.

This is the core tenet of provocation.

Therefore, a provocation should start by moving to achieve a strong position: using both forms of structure, keeping the eyes on the sword hand of the opponent, and reacting in accord to their movement or lack of movement. This loops back to our tree of ifs outlined above. The cycle perpetuates until the opponent is so discommoded that you’ve achieved a strong position from which you may attack their person. Or, if you catch them in tempo, they're slow to react, or just don't see the attack, then you may proceed with your attack at the outset.

Manciolino outlines a similar framework, advising:

“Since no blow can be reasonably performed without ending in a guard, the virtue of a fencer is to be found in the raising and lowering of the guards. In consequence of this principle, he who renews his attack before settling in guard will be more apt to win. This is because it is easier to attack an opponent whose action is interrupted.”

—Manciolino, Main Rules or Explanations on the Valiant Art of Arms ; Leoni, pg. 112

Manciolino echoes Marozzo’s sentiment of catching the opponent in the tempo of their raising to or lowering into guard. Note the added clarification, he who renews his attack before settling in guard. This is keen advice, which further emphasizes this notion of Frequens Motus. That is, you don't want give up the pursuit of position until you're guaranteed of success.

We can reduce this in a number of different ways: manipulating the opponent out of position, creating a tempo, climbing the opponent’s sword, or forcing them into an instinctual response. Fabris defines this as putting the opponent in obedience.

This method of fencing creates beautiful conversational fencing. It will help you prevent unnecessary doubles, and have more control of what happens in a bout. Sandro Francesco Altoni describes it like this:

In fighting with the unaccompanied sword, the key is getting control over the opponent’s sword. Then you can raise it and lower it with perfect rapidity and can also defend yourself against any blows your opponent will make by setting your sword across the enemy’s cuts and thrusts. Do this until an opportunity arises for a better action. The one who has gained control of the opponent’s sword will make small feints trying to fool his opponent. If possible, you will make one turn after another, and seek that place where you can sheath your sword, remembering to push your sword, and bury it in your enemy up to the cross. This is a beautiful way of attacking and defending.

—Altoni, Monomachia; Fratus pg. 64

The beautiful thing about this theoretical framework of attack is that it's inherently simple—it just takes practice and patience. Your attacks should be simple: mandritto, roverso, stocatta. The complexity of your attack is predicated on the tempo and movement of your opponent, and the relationship of strength and weakness.

Developing an understanding of these principles will also enlighten the more complex attacking actions found in the Bolognese corpus, and bring often overlooked nuance to bear. Take for example the Falso Impuntato: this attack with often originates as a mandritto that seeks to gain a position of strength (Coda Lunga Stretta to Cinghiara Porta di Ferro), meets the strength of the opponent, and weakens amidst their strengthening to snap the false edge toward their temple; as the opponent carries their defense further afield, you can abandon this high-line assault to seek a new opening with a Roverso tondo (Marozzo: sword alone) or a cut to the leg (Marozzo: due spada, sword and large buckler).

The cadence of this attacking theory has its roots in dance. You are both leading the engagement, and following the cues of your dance partner. If you fail to follow the cues of your opponent, and take your eyes off of their sword hand, you’ll lose the plot and act injudiciously. Similarly, if you allow them to complete their strengthening and achieve their desired guard, you've forfeited the lead in the engagement, and now you must change your role.

And so, in combats a man should accustom himself not to hit, but to conquer.

—Altoni, Counter Postures; Fratus, pg. 20

The Role of the Defender:

Now that we’ve defined the role of the attacker, it's time to do the same for the defender. Ready?

Gain control of the attackers sword.

That's it, done and dusted. Finito.

As simple as the principle of defense is, it is also the most artful and complicated. There is a reason why an author like Manciolino spills so much ink on the art of defense, and lauds the artfulness of defensive fencing. It's hard.

The objective is simple, but the means of effectively executing a successful defensive action are infinitely more complex than the objective they seek to achieve. At a base metaphysical level, we can simply define this as interrupting the opponent’s Frequens Motus.

Fortunately we have pages upon pages of materials to work from, but rather than rehashing countless anecdotes, I'm going to sum it up in a number of key responses (i.e., guard positions) and well thought out principles propounded by the authors themselves.

The first key: watch the opponent’s sword hand. While the Anonimo says that the number of guards are infinite and innumerable, and Marozzo surely does his best to validate that notion, we have an erudite exemplar of keen tactical reason in Angelo Viggiani to guide our way. This was briefly mentioned above, but it bears repeating, and for good measure we’ll add some poignant advice from Antonio Manciolino:

Point on-line (perfect): Can both cut and thrust.

Point off-line (imperfect): Can cut.

Guards on the right: offensive

Guards on the left: defensive

Guards that are low: The natural attack is a thrust; and are inherently defensive. (Parry first, then strike)

Guards that are high: Are inherently offensive. (Strike first; then parry)

Having foreknowledge of the potential of the opponent’s guard position will give you some insight as to how they intend to proceed. This is a keen tactical advantage for the defender. It’s also instructive for how you should proceed in the role of the defender. If you are stationary in guard, inviting the opponent to attack, and remain fixed in advantage, holding a high, wide or inherently offensive guard, then this choice of position comes with a certain amount of risk and needs to be considered in how you react to your opponents movement into measure. Knowing what may come, and what advantages or disadvantages your guard positions holds, will help you choose the correct guard for your parry in order to interrupt the opponents attack and reclaim the initiative, but to do this artfully we need to examine the guards that will help us achieve that objective.

Flipping the Script

Just as you should not strike without parrying, you should not parry without striking—always observing the correct tempi. If you were to always parry without striking, you would make your timidity plain to your adversary, unless you were to push the opponent back with your parry, in which case you would show your valor. Correct parries, in fact, are performed going forward and not backward; in this manner, you can not only reach your opponent, but you will also attenuate his blow against you, as from close by the opponent can only strike you with the part of the sword from mid-blade to the hilt; much worse it would be if he were to reach you with the other half of the sword.

—Manciolino, Main Rules or Explanations on the Valiant Art of Arm; Leoni, pg. 111

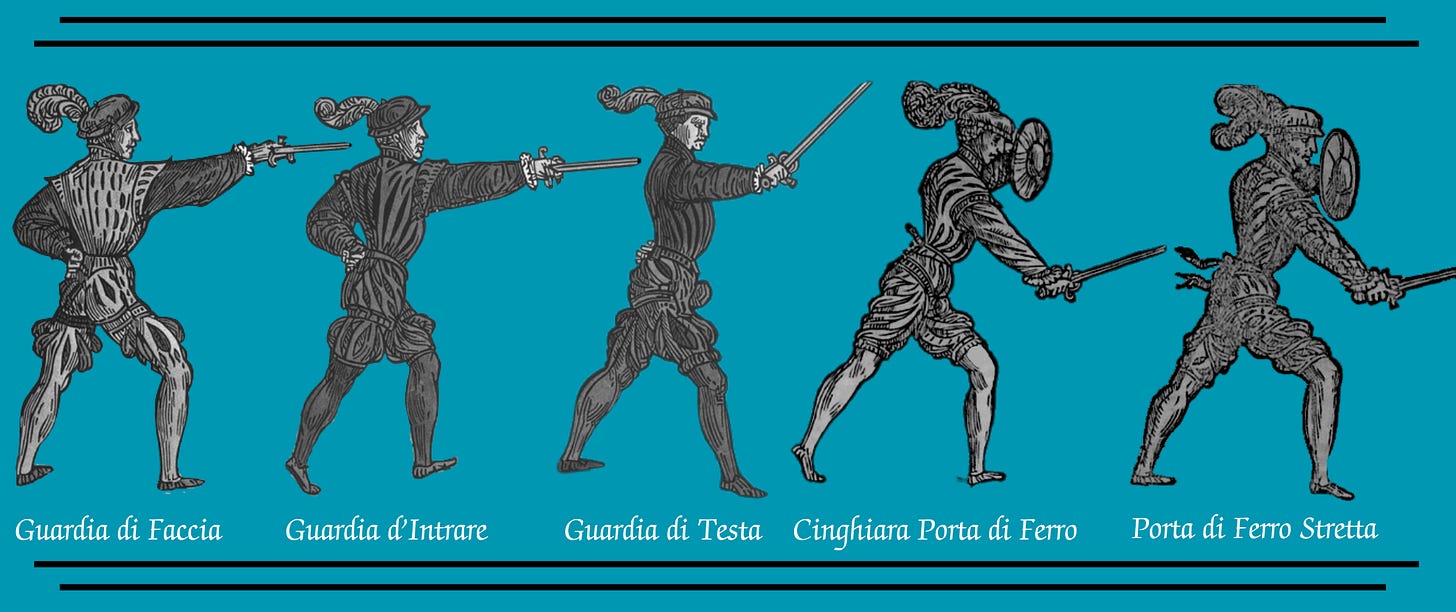

There are a few recurring principal guards that the Bolognese authors prefer to interrupt the opponent’s attack, and they are: Guardia di Faccia, Guardia d’Intrare, Porta di Ferro, and Guardia di Testa. Of these principal guards, there are variations of each:

Porta di Ferro:

Porta di Ferro Stretta or Lunga (right foot forward)

Cinghiara Porta di Ferro (left foot forward)

Guardia di Faccia: the direction of the point will be affected by the orientation of the hips. You can try the previously illustrated exercise with the hand in Guardia di Faccia, and see who a turn of the back foot re-orients the sword and covers the line on the inside and outside based on the direction of the hips.

Right foot forward, hips forward (parries the outside line)

Right foot forward, hips profiled (parries the inside line)

Guardia d’Intrare: Similar to Guardia di Faccia, the orientation of the hips determines the line that the guard covers.

Left foot forward, hips forward (parries the inside line)

Left foot forward, hips profiled (parries the outside line)

Guardia di Testa: Is almost always directing the opponent’s weapon toward the outside line—except dall’Agocchie’s hanging di Testa, which takes the opponent’s weapon to the inside.

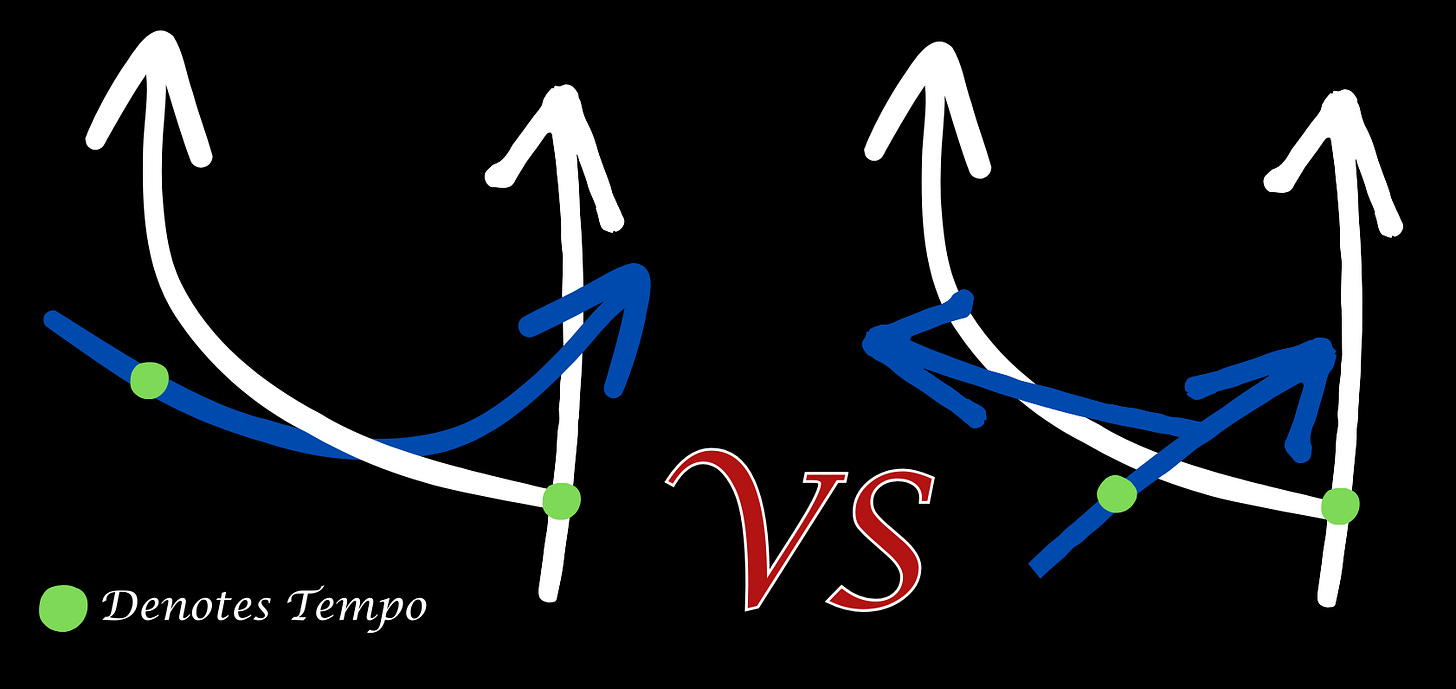

This triangle of defense is sufficient to cover the upper half of the body, but there is more to it than that, and it's the hidden nuance that really brings the art to light. Each of these guard transitions, when accompanied with a step or a turn of the hips, has the capability of catching the opponent’s sword and giving the defender the ability to turn their defense into offense. Better yet, keeping your defensive actions within this triangle will allow you to gain tempo on the attacker, by forcing bigger motions from the attacker with each subsequent attack, while forming reliable defense with half (mezza) tempo actions.

The common actions that utilize these guard transitions are omnipresent in the Bolognese corpus: perform a falso that does not go past Guardia di Faccia, execute a mezzo mandritto that goes into Cinghiara Porta di Ferro, parry in Guardia di Testa, so on and do forth.

Returning to the advice of Manciolino at the heading of this section, a common trait shared by these guard positions is the arm being well extended18, going forward. This driving, aggressive defense will often rob the attacker of their initiative, and force a passage of play that will allow the defender to go on the attack.

Now, these defenses have tempos of their own, if you’re reading Viggiani. This is when the opponent is in disadvantage and you are in advantage, if you're reading Giovanni dall’Agocchie. These are the five tempos of attack19.

This is will strike many readers as an odd statement at first, but allow me to explain.

The Five Tempos of Attack:

Once you’ve parried your enemy’s blow.

When their blow has passed outside your body.

When they raise their sword to harm you.

As they injudiciously move from one guard to another.

When the enemy is fixed in guard, and he raises or moves his forward foot in order to change pace or approach you.

All five of Giovanni dall'Agocchie's tempos of attack can be analyzed through this metaphysical model and Viggiani’s advantages, to render an underlying bias toward defense. This is intentional, and will be further substantiated below. But, for now, let’s view them in their purely defensive connotation.

When you’ve parried your enemy’s blow: Note that with the framework we’ve established, this is predicated on when you’ve halted the momentum of the enemy’s attack. Simply counterattacking when the opponent may have proceeded to another line is not the answer; you’ve made your defense when the Frequens Motus of the attacker has been interrupted. Put more concisely, this is when you have forced a bind. From a metaphysical standpoint, any attack coming forward will be weak, and if you can complete a strengthening action, and overtake the weakness of the attack, then you are obliged to reply with an attack (weakening action) of your own.

When their blow has passed outside your body: This is often perceived from the standpoint of the opponent’s attack missing, or the defender voiding the blow of the attacker, but I would like to add a third, more Bolognese, explanation to this list: when you’ve performed a beat. The droves of praise heaped on the false edge parry, and the devilish delight of driving the opponents weapon toward the ground are a stark reminder of one of the core tenants of the Bolognese fencing. The great 20th century courtier Michael Jackson, whose poetry and fine dancing dazzled the world, perhaps said it best—just beat it. Falsos to Guardia Faccia, and the tendency of Guardia di Testa to help an opponents attack along its desired path, create lots of counterattacking opportunities.

When they raise their sword to harm you: Returning to an earlier quote from Antonio Manciolino on the nature of the guards, where he says, the only natural attack from the low guards is a thrust, we can deduce a number of key things about this tempo of attack. If the opponent is in a low guard and attempts to cut, they will have to raise their hand in some fashion, this can be more of an elbow cut, or a full shoulder cut, and even a wrist cut (though the point usually lowers with a wrist cut). In the time of the opponent’s preparation, you can begin your strengthening action—usually Guardia di Faccia—and interrupt the opponent’s attack; i.e., or when one parries and attacks in one instant, as dall’Agocchie puts it.

The next two certainly have their offensive inclinations, with a potential defender rendering advantage by changing guard in measure or moving forward from a fixed position to follow an attacker, but I’m going to show how these also fit within the framework of defensive tempos to reclaim initiative.

An injudicious guard change: This has two facets that need to be covered. First, if an attacker is approaching the defender, and changes their guard in measure, then the fencer in advantage (the defender) may come forward with an attack in the tempo of the guard change. Second, if an attacker has initiated their attack and strengthens; i.e., changes guard (as the endpoint of every motion is a guard; Viggiani) when they should be weakening, then this is a tempo for the defender to attack. Similarly, if the attacker weakens when they should be strengthening, then this is a tempo to attack. Both examples highlighting an injudicious guard change, or a misread of leverage in the course of an exchange.

When the enemy is fixed in guard, and he raises or moves his forward foot in order to change pace or approach you: If the opponent recognizes your desire to fence with advantage, and they are in a position of advantage (i.e., fixed in guard), then their movement toward you to initiate an attack, or to gain measure so they can begin an attack, is a tempo to leave your position of advantage and attack. This concept is illustrated quite nicely in Capoferro’s Gran Simulacro.

Overall, this concept of fencing with advantage is propounded by a number of authors in the Bolognese corpus, with exemplars like Manciolino, Viggiani, dall’Agochie, and at times Marozzo all lauding the advantage of this defensive style of fencing. It is, as mentioned, the safest way to approach a fight until you have a firm grasp on how your opponent wishes to fence.

If the opponent wishes to attack you while you’re in advantage, then you can use your smaller guard transitions to strengthen and halt the momentum of the opponent’s attack in tempo, whereupon you may then weaken and come forward with an attack of your own. At this point, the roles are reversed, and now you are on the attack, looking to establish frequens motus, and the opponent should be looking to reclaim the advantage by forming quick decisive defensive positions until they have halted the momentum of your attack, whereupon they may resume their attack. If this occurs, the resulting exchange will become conversational, and beautiful.

Like any good conversation, the key to understanding when to speak and when to listen is to be attentive to the cadence of the conversation. If one begins to talk over the other; i.e., goes on attack when it’s not their role to be attacking, or fails to recognize when their offensive momentum is spent, then doubles will often result. A good exercise to reinforce this is to break down each exchange with your fencing partner, and determine whose role was the attacker and whose was the defender during the course of a bout. Then determine whether they were acting within their role when a touch occurred, and use this a constructive mechanism to coach one another during a training session.

Full gear sparring, but you stop after every touch, and talk about what happened using the terminology discussed in this article.

Determine after every exchange:

From the onset, who was the attacker and who was the defender?

If attacker: Were you successful? Why or why not? Did you maintain Frequens Motus?

If defender: Were you successful? why or why not? Did you try to interrupt your opponent’s attack?

If it's a double, then who failed to correctly assess their role? Was it at the onset, or was it after a change in roles in the exchange?

Rotate partners as much as possible.

Three General Rules:

1. Watch the opponent’s sword hand

2. If attacking: try to maintain Frequens Motus.

3. If defending: interrupt your opponent’s intention to reclaim initiative.

Third Tier Tactics:

Once you’ve become sufficiently proficient in the two second tier roles, then the tactical complexity of the Bolognese fencing system will open its petals and begin to flower. From there, you can begin to explore the tier three concepts illustrated throughout the corpus.

Provocation as an Invitation

This is best defined as provoking to encourage a counterattack. The reason for this being a higher tier of fencing is simple: if the opponent doesn't understand the concepts outlined above, especially in the role of the defender, then it's not necessary to elicit a counter-attack.

To the contrary, if they're actively trying to interrupt your attack to establish a strong position, so they can counterattack, then using a provocation to lure the opponent into a weak position as they counterattack is an effective tactic. In order to do this effectively you need to have some knowledge of how the opponent is going deliver their follow-up attack.

Now having understood how tempi are born from attacks, you will understand that attacks are born from tempi in this way. For it is of great necessity to every person to first recognize the tempo in which you make your attack. Because if you stir or throw an attack without recognizing the tempo, you will not do it well. And though the tempi are born from an attack, nevertheless it is necessary to recognize the situation of the tempo, in particular the situation where you are throwing an attack. Because if you wish to throw some attack without knowing the tempo, you will do so blindly and will be unable to make it well, insofar as it is necessary to first know the tempo and then to make the attack, if you wish to proceed artfully.

—Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 64

This knowledge, as the Anonymous author and Manciolino love to say, is born from experience, as experience is the mother of wisdom. In order to enjoy the fruits of wisdom, you must first gain the experience of fencing in both roles. Both the role of the attacker and the defender will render an understanding of how the other should proceed.

From the standpoint of the attacker, you will come to realize how a defender can best interrupt your attack; i.e., you'll understand the tempo you're giving.

From the role of the defender you will learn how to interrupt various attacks and the most appropriate counterattack once that position of strength in achieved.

Having this foreknowledge or wisdom will afford you the ability to devise a counter to the counterattack you're receiving.

For those familiar with the Swiss-born fencing master Joachim Meyer, the cadence of this assault will read similar to his famed Provoker, Taker, Hitter. This framework isn't unique to the Marozzo-inspired late KdF master however; Manciolino propounds a similar ideology. In the quote referenced above, about defending going forward, Manciolino advises that every defense should be followed with an offense, and every offense with a defense.

When we take that advice and apply it to this theoretical model, an attacker would provoke with their strike, then defend the counterattack, whereupon they could come forward with their intended attack (provoke, take, hit), chaining the series of advised progressions together. Similarly, an advantaged fencer may defend, then counterattack, whereupon they'll have to defend (strengthen) from their weak position if the attack does not land, and the cycle continues.

Viggiani calls this back-and-forth, turn-based style, Germanic fencing.

CON: When I think over that which you have said to me just now, I find a clear example in the Germans, who, coming to an armed brawl, deliver a blow per man, and delivering the blow, stop in guard in order to wait for their companion to deliver his, and withhold theirs, and then redouble; behold the two rests with a motion in the middle.”

—Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 28

This observation isn't derogatory; both Marozzo and Manciolino had deep ties to the German University in Bologna. One could argue that many of the suppositions proposed of these methods are integration, and some of the techniques that seem to counter them are answers to questions being asked in the process.

Of course, these tactics undoubtedly show up quite a bit with Achille Marozzo in his sword and dagger and two sword sections, which tactically makes sense with the dominance of the dagger and a second sword sword as defensive sidearms. Whereas with the sword alone, and in his sword and buckler/targa sections, we see a more driving offensive style underpinned by keen defensive fencing that seeks to reclaim a dominant position. One trait that the aforementioned chapters of Marozzo's Opera Nova share is a hefty dose of invitation through disadvantageous position.

Invitation of Disadvantage: It's a Trap!

A fencer confident in their skills will often invite an attack by holding a disadvantageous position. A guard like Porta di Ferro Larga is a perfect exemple. The challenge of attacking a point off-line position like Porta di Ferro Larga is outlined by the anonymous author:

Also, you must know that if you find your enemy in a wide guard, then you will use your art to bring his sword into presence. If he has his sword in presence, then you must, by means of feinting, make him put his sword into a wide guard that allows you to control the line, such that his sword will point away from your person and off to the side of your body, and so you will then be able to perform whatever action you wish.

—Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 75

This is one of the most succinct pieces of advice for how to attack. However, the reader should note the inverse progression of this quote. When the opponent’s point is on-line you must, by means of feinting, take their point off-line so you can strike them (strong position); if their point is off-line, you must use your art to bring it on-line—so you can take it offline and strike them.

The advantage of wide guards, and thereby wide play, is that the attacker has to work an extra tempo to create a predictable situation. As the attacker, utilizing wide play in your entry denies many of the direct in-tempo attacks an advantaged fencer has at their disposal. The reason is that their first attack must be a threat to draw the attacker’s point on-line before proceeding with any sort of resolution—unless they're suicidal.

With that in mind, an attacker may lure an advantaged fencer into a provocation to get them to relinquish their advantage, and use their own defensive actions to create a complex attack. Some great examples of this can be seen in the entry into mezza spada actions in Manciolino’s sword and small buckler assalti (Book 2), Marozzo’s book two of sword and small buckler (wide play into narrow play), and Marozzo’s sword alone section.

Contratempo:

If the opponent is too capable of contending with these tactics or seems to divine your well-laid traps, then Antonio Manciolino gives some fairly pointed advice on how to deal with them:

If you and your opponent are of equal knowledge of the Art and neither can safely deliver an attack to the other, I advise that you take a chance in your hope for victory. You can either rely on your reflexes and attack in the same tempo as your opponent, or you can strike him wherever you can and immediately spring against him and put your arms around him. By doing this, everyone will judge you the victor.

—Manciolino, Main Rules or Explanations on the Valiant Art of Arm; Leoni, pg. 112

Contratempo actions, defined earlier as coming to a defensive position that both parries the opponent’s blow and attacks them in the same tempo, are often characterized as bold fencing actions. Manciolino doesn't shy away from defining similar stakes, stating that you should, take a chance and hope for victory, when resolving to come forward with contratempo actions.

While guards like Guardia di Faccia are notorious for their contratempo capability, the risk that Manciolino is outlining comes more from the timing of the encounter. Here he is specifically talking about a skilled fencer, who is keying on your movement in tempo to alter their line of attack, as outlined above. Therefore, there must be some belief that the strike will land, and by consequence some patience from the defender in letting the strike develop for the attacker to commit.

It's worth pointing out that contratempo actions are fairly easy tactics to employ against unskilled fencers who are too committed in their attacks, but this can easily lead to false confidence that can be exploited by the attacking principles outlined in this article.

The timing required to catch a more astute fencer in contratempo is incredibly minute, and requires a fair amount of risk and confidence. Therefore, they should only be employed as a last resort. While Guardia di Faccia is sure to become a staple in your defensive repertoire, the prudent approach of getting the timing just right is what needs to be tempered until the moment of realization that all of your other tools have been exhausted.

A clearer explanation of this might be found by saying, it’s better to start your motion in a time that will keep you safe and give you time to react if the opponent changes the line of attack, than it would be to risk their attack coming to completion or departing the line when you're in the process of coming forward.

The follow-up to any contratempo counter should be mezza spada, and here Manciolino caps this statement off by advising that, even if this counter fails, you'll be able to quickly employ a grapple of some sort, whereupon you'll be judged the victor.

Mezza spada, or a crossing at or below the middle of the sword to the hilt, is the ultimate objective, and the final destination of many of the above-highlighted actions. Marozzo outlines this nicely in Capitolo 35 of his Opera Nova, where he states:

When you’re at the true edge, or the false edge, there are many prese of the sword that you can do, and many feints, and turns of the pommel, as you know. You can feint riversi but throw mandritti, or feint mandritti but throw riversi, and even feint riversi and throw riversi, and more kinds, and also you can feint riversi but throw falsi. Given all this, it should come as no surprise that when you come to the aforesaid two modes of the half-sword there are a great number of things that can be done. Yet I tell you that there are few people who display clarity when they’re at the half-sword, whereas those who understand and know how to enter into and exit from those two modes of the half-sword are excellent and perfect fencers, who are familiar with tempi; whereas those who don’t know how to perform the aforesaid art can’t recognize tempi, nor mezzi tempi, so they cannot be perfect fencers. God may will that when they fence against other fencers they sometimes make a touch on them, but they don’t make the touch through their knowledge, but rather through luck, and this is because they are not well-founded in the art of the half-sword.

—Achille Marozzo (Swanger; pg. 111)

Now that we’ve discussed the various ways and means of fencing that will lead us to our mezza spada techniques—measure, tempo, and attacking and defending theory—it's time to discuss the art of fencing at the half sword. If you'd like to follow along, take a moment and subscribe. It's free unless you'd like to contribute financially.

If you liked this article, and you want to support our work through means other than a recurring paid subscription, checkout our webstore, and the featured shirt for this article, Just Beat It! Show your friends in the fencing ring who the real the real king of pop is when you drop the beat on their weak responses. he—he!

You can also go pick up a copy of Stephen Fratus’ translation of Sandro Francesco Altoni’s Monomachia: Here

Attribution:

This article is the fruit of hours of practice and patience on behalf of my students, and many more hours lovingly discussing the metaphysics of fencing with my good friend James Reilly, whose influence has had a tremendous impact on my perception of the rules that govern fencing.

Works Cited:

Fratus, Stephen. “With Malice and Cunning: Anonymous 16th Century Manuscript on Bolognese Swordsmanship.” Lulu Press. 18 February 2020. Print.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Duel, or the Flower of Arms for Single Combat, Both Offensive and Defensive, by Achille Marozzo.” Lulu Press. 22 April 2018. Print.

Leoni, Tom. “The Complete Renaissance Swordsman: Antonio Manciolino's Opera Nova (1531)” Freelance Academy Press. 27 May 2015. Print.

Swanger, Jherek. Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Dell’Arte di Scrimia, “The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation”, lulu press, May 5, 2018. Digital.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Schermo of Angelo Viggiani dal Montone of Bologna.” 2002. Digital.

Swanger, Jherek. “How to Fight and Defend with Arms of Every Kind, by Antonio Manciolino.” Lulu Press. 4 February 2021. Print.

Fratus, Stephen. “The Monomachia: The Fencing System of Francesco Altoni.” Art of Arms Press. 1 September 2024. Print.

Termiello, Piermarco & Pendragon, Joshua. “The Art of Fencing; The Discourse of Camillo Palladini.” The Royal Armories. October 2019. Print.

“(I)t is the movement of the sword that creates a tempo, and these tempi come from the attacks of the sword. Thus, as soon as you move your sword you will give birth to the tempo it creates.” (Anonimo; Fratus; pg. 64)

“Said provocations, so that you understand better, are performed for two reasons. One is in order to make the enemy depart from his guard and incite him to strike, so that one can attack him more safely (as I’ve said). The other is because from the said provocations arise attacks which one can then perform with greater advantage, because if you proceed to attack determinedly and without judgment when your enemy is fixed in guard, you’ll proceed with significant disadvantage, since he’ll be able to perform [24verso] many counters.” (dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 27)

“You have to know, Conte, the advantage now can be considered to be in settling yourself in guard, in the striking, and in the stepping.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 24)

“Accordingly it may be said that you settle yourself in guard with advantage when the point of your enemy’s sword is outside your body and not aimed at you, and when the point of your sword is aimed at the body of your enemy in order to offend him, so that you may, in such fashion, easily offend him, and it will be difficult for him to defend himself from you; consequently you will be able to strike him in little time, and in order to defend himself, he will require more time; and conversely, he will find it difficult to offend you, and you will be able to easily [61R] defend yourself from him for the selfsame reason, he having need of much, and you of little time.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 24)

“Therefore, Conte, from your perspective you have the advantage in the strike when you can hit in one step, or half of one; and from the perspective of your enemy, when he would try some blow without being able to reach you, or being able to reach you in more steps, because he, in disconcertedly attempting his blow, or in the elevation of his sword, will give to you time in which to strike him, and similarly, when he, not having regarded the point of your sword, will give to you occasion to offend him.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 25)

“Briefly I tell you that when the enemy, in stepping, lifts his left foot in order to move a step, that he is then a bit discommoded, and then you can strike him with ease, and again change guard without fear, because he is intent on the other; and this is from the perspective of the enemy. From your perspective, then, when you are stepping, approaching the enemy, and go closing the step, then you have much advantage; for as much closer as you are with your feet, you will have that much more force in your blows, and in your self defense, and otherwise accordingly will you be able to close with your enemy in less time.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 25)

“Knowing that you cannot attack your enemy with technique and advantage without knowledge of measure, I undertake to explain what I understand of it, insofar as I am able.

The reader should therefore be aware that I want you, having drawn your sword from it’s scabbard at some distance from your enemy, to move to meet him gallantly and with heart, as such endeavors demand. Having advanced to within two or three steps of him, remaining sufficiently covered against any attack he might attempt, you can then exercise your judgement to determine the spot where you may attack. You should approach until you see that by extending your arm and stepping with your right foot you may wound him, either with the point or the cut, depending on the opportunity or situation.” Anonimo

This is termed the misura di ferire, and you must practice this measure many times in order to seize it when needed, since you cannot use a compass against your enemies in disputes. Neither do any deride this method, since it is the means of attacking securely, which you will see through practice. If however you do not observe this method, you risk a response from your enemy’s sword.” (Camillo Palladini; Terminiello, pg. 69)

“Therefore I want to advise you that you mustn’t be the first to attack determinedly for any reason, waiting instead for the tempi. Rather, fix yourself in your guards with subtle discernment, always keeping your eyes on your enemy’s hand more so than on the rest of him.” (dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 27)

“So that the art will become clear to you, I'll add that if you face an armed opponent, you should make a point of keeping your eyes on his weapon hand rather than on his face. His face may deceive you, but by watching the movements of his sword hand, you may deduce all his designs, whereas looking upon his face may deceive and unreasonably intimidate you.” (Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 71)

“ROD: Don’t you see whether the sword is hindered in the way it is advanced toward the enemy, that to offend him it is very close? “Offensiva” it is, then, through being on the right side, from whence (as I have told you many times) are born all the offensive guards and blows.

CON: The Most Excellent Francesco Maria, Duca di Urbino, of his age a man of valor, knowledge, and prudence (according to a few), praised beyond measure this final guard of yours, and placed it before nearly all others. But let’s return all over again, please, Illustrious Rodomonte, and do these seven guards, as an epilogue, telling along with them the origin of each one.

ROD: I am happy to do this, and every other thing for you, Conte. The first guard is “difensiva, imperfetta”, generated from girding the sword at the hip, and it is a tempo, or motion, defensive and imperfect. The second is “guardia alta, offensiva, perfetta”, made from the rovescio, which is done in the drawing forth of the sword to on high, a full, defensive blow. The third is “guardia alta, offensiva, imperfetta”, made from the same full rovescio. The fourth is called “guardia difensiva, imperfetta, larga”, born from the full punta sopramano perfetta, or alternately from the mandritto sopramano, descendent down to the ground, and full. The fifth is called “guardia difensiva, perfetta, stretta”, formed from the incomplete punta sopramano, or alternately from the mezo mandritto sopramano, descendent down only as far as the right knee. The sixth is called “guardia offensiva” k, born from the second full rovescio difensivo. The seventh and last is called “guardia offensiva stretta, perfetta”, formed from the mezo rovescio difensivo. Behold each in order, according to how we have done them. You see now, Conte, how each [76V] blow, or motion lies in between two guards, or rests, and each guard in between two blows?” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 46)

“This way when you find yourself against an enemy, you can immediately identify how the swords are placed, for the attacks one may make with the sword are infinite and innumerable, and so too are the ways in which the swords may be found; yet from one guard or another, not all attacks will be suitable, and by being shrewd, and also being illuminated with the knowledge of your enemy's placement, you will make effective attacks, in the correct tempo, using your sword and your body; and by making attacks in this manner you will remain secure from harm.” (Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 66)

“While you and your opponent are studying each-other, never stop in a particular guard, but change immediately from one guard to the next. This will make it harder to judge your intentions.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 110)

“But if it should happen that you do not attack him in his rising or in his falling, I warn you that he can disrupt your intention with more blows, so when you want honor, be careful and watch to attack him in his falling or in his rising of the guards, with his opposites. But note that if you find one whom you have not gone as I have told you, make sure that you embellish the play, so that he comes to move, making you understand that he cannot move without going to some guard, and you then find him with his opposite, and in this way you will have honor. Again I want to teach you, that no one will ever be able to find you in any of the ways I have mentioned, if you make sure to never stand still in any guard, that is, be certain that when one guard is finished the other is started, and in this way he will never be able to catch you in rising or in falling.” (Marozzo; Wiest, Capitolo 171)

"You need to make thrusts with control. Do not fling them forward as most men do. When you fling your thrust out then you will lack control, and it loses its virtù and becomes less certain. When your sword hand makes the thrust so that that the point remains always in control, you will be able to place it where you wish. If the need arises to pull it back or to put it into a guard so that you may stringere the opponent, you can do this most aptly and without discomfiture." (Altoni, Monomachia; Fratus, pg. 24)

A number of quotes to emphasize the movement of the sword and the body together:

“Making all of those turns of the body, the hand, and the feet, of which I taught you in the other guard.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 34)

“(U)ntil it comes forward as far as it can come, and then, turn there the true edge of the sword toward the left side, and from here you descend finally to the ground, and it is necessary that you make a half turn with your body at the same time that the blow is traveling, so that your right shoulder is somewhat lower than your left, and that it faces my chest; and the right foot trailing behind somewhat, bring yourself to rest again in good stride, and settle your feet, which are on the diagonal, and bend your knees a bit, and cause your sword hand to be located halfway between your knees, and your left arm to lower from high to low during that tempo in which the point will travel, and it will go back and by the outside with the left leg somewhat extended.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 36)

“…(D)o all those turns of the body, of the hands, and of the feet, that I told to you…” (Viggiani; Swanger pg. 41)

“Wishing, Conte, from some defensive guard, either stretta or larga, to make the 91same rovescio with all of those turns (still with the right foot forward) of the body, the hands, and the feet, as you know; it will be necessary for your sword hand in descending to not pass lower than your knee, but that you stop it outside and a span forward thereof, and that the point of your sword aim toward my chest (you see how I do it?) and this blow will be a mezo rovescio, not having made other than half the path of an entire rovescio, and it will frame you in a guardia stretta, offensiva, which will be our seventh.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 44)

“(N)ot forgetting to do all those turns of the body, of the hand, and of the feet mentioned above.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 52)

“Always teach your students how to walk from guard to guard—forward, backward, and sideways, obliquely and in any other possible manner. Do this especially with sharp weapons—that is, with targa, rotella, large buckler, single sword, and cape, sword and dagger, and two swords. Teach them to let their hand be in agreement with their feet and vice-versa, or else your instruction will be defective.” (Marozzo; Leoni, pg. 10-11)

Although it is undoubtedly useful and beneficial to walk with one or the other foot (depending on the tempo or the occasion) as you fence, I personally think that it is preferable to always walk even-footed, since doing so will allow you to extend forward and get back without disordering your body. Also, let me add that walking in this manner will keep you stronger than doing so in any other fashion. When I say “evenfooted” I mean in such a way that the feet are never more than half an arm’s length apart, and that the foot and the hand always accompany each other. (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 113)

“Those who learn how to parry the opponent’s blows with the false edge of the sword will become good fencers, since there can be no better or stronger parry than the ones performed in this manner.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 113)

“If you want to strike your opponent in his upper body, you should begin your action below; similarly, if you want to strike him below, you should begin your operations above. This is because as one defends the parts being attacked, he necessarily creates openings elsewhere.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 112)

“As you parry on whichever side, always keep your arms well-extended. By doing so, you not only push the opponent’s attacks away from your person, but you are also stronger and quicker in striking him.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 112)

“Gio. Since you give me an occasion to speak of tempo, I’ll tell you. {The tempo for attacking is recognized in five ways.} There are five ways of recognizing this tempo of attacking. The first one is that once you’ve parried your enemy’s blow, then it’s a tempo to attack. The second, when his blow has passed outside your body, that’s a tempo to follow it with the most convenient response. The third, when he raises his sword to harm you: while he raises his hand, that’s the tempo to attack. The fourth, as he injudiciously moves from one guard to go into another, before he’s fixed in that one, then it’s a tempo to harm him. The fifth and last, when the enemy is fixed in guard, and he raises or moves his forward foot in order to change pace or approach you, while he raises his foot, that’s a tempo for attacking him, because he can’t harm you as a result of being unsettled.” (Giovanni dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 32)

"Fencers who deliver many blows without any measure or tempo may indeed reach the opponent with one of their attacks; but this will not redeem them of their bad form, being the fruit of chance rather than skill." —Manciolino, Main Rules or Explanations on the Valiant Art of Arms ; Leoni, pg. 112

Manciolino was right. That's how I feel right now. My resolution is to try and stick to the manuscripts, and learn how to do things right. When people start HEMA, just swinging the sword at an opponent is fun (and encouraged as a first experience to hook people in from what I saw), learning basic guards and attacks is fun, and performing basic drills is fun. But after a while, if they keep going, people will either move towards a sport approach centred around a weapon, or try to deepen their understanding of particular old works. I'll go with the latter.

I plan to do seasons... that is, 3 months of focusing on one manuscript and one weapon, and then move on. This way, there is a structure to the study such that I can advance while satisfying the drive to experience more.

This is nice to see it all written down and defined. I'm happy to see my understanding of offense is in acordance with the article.

I liked the relation to dance because during the attack the opponent is following my lead and I'm just double checking cues to ensure their following me. If they're not then I have to abandon my lead and start to follow to maintain the beautiful show and more importantly to avoid getting hit. It's just like the conversation, someone has to give or else it's just two people yelling at eachother.

The defense section is definitely more complex and I'm not quite there yet in my journey but I understand the basics of parrying and counter attacking from guard. But just like masters said, it's only through experience that you'll come to understand the correct tempi. I feel like the hard part is seamlessly transitioning between the different aspects of the fight.

One of the counters that I absolutely love although it is fairly simple comes from Manciolino's book 1.

The attacker

Standing in PdFL presents a drilled thrust then turns a Strammazone

The defender

Standing in PdFL as well, raises into GdF to parry the thrust, at the turn of the strammazonne throw your own with a left foot step and strike thier sword arm.

The strammazzone vs strammazone is seen a few places but I love it because the prep phase of turning the blow clears their strike and the finishing phase delivers the wound on the Fendente line inbetween the sword and buckler to the sword arm. It captures the essence of interrupting Frequens Motus and seamlessly transitions from defense to offense by capitalizing on Giovanni's tempos to attack safely.

I'm eager to learn more about mezza spada. I haven't dedicated a lot of time to that section yet but I know it vital.

Great work! Looking forward to future articles! ⚔️