The Soldier and The Philosopher

How Angelo Viggiani Used Aristotle to Sculpt his Schermo

Introduction:

Many theories have been postulated as to why Angelo Viggiani del Montone decided to rename the guards of the Bolognese fencing tradition in his 1551 work, lo Schermo. I’ve argued for a number of them myself, ranging from Viggiani being a heretic to writing for a multicultural audience to simply being a reformer, looking to modernize the tradition. In this article I intend to dispel the first, address the second, and validate the third with a deeper look at the philosophical backbone of his innovative schermo.

First an acknowledgement, and an address as to how I came upon this new line of reasoning.

This journey to uncover why Viggiani approached his schermo the way he did came to me rather organically. Like many scholars of Bolognese fencing I enjoyed the thoroughness of Viggiani's explanations, his descriptions of body mechanics, and his discussions on tempo and advantages. Despite this, my perspective on his guards ranged from satirical condemnation to genuine curiosity. However, it wasn't until I started to view Bolognese fencing with a Renaissance mindset that I truly began to appreciate the masterful nature of his work.

The first person to show me the cavernous tunnel that would produce this rabbit hole was Rob Runacres, whose 2022 paper, The Bolognese Tradition: Ancient Tradition or Modern Myth, introduced me to Giovanni Filoteo Achillini. Through a series of corresponding private conversations, Rob encouraged me to pursue information pertaining to Giovanni’s brother, Alessandro, and it was upon this quest that the flood gates began to open.

In my subsequent pursuit to understand the influence of the Università’s influence on Bolognese fencing I produced a paper titled Marozzo’s Razor. Then, in the summer of 2024, I put together a lecture called Who Are We? Scholasticism in Fencing for WMAW. The objective of this lecture was to layout a landscape of various fencing authors who inundated their work with scholastic ideas, with the hope that curious observers would explore the subject on their own. In the process of constructing this lecture I was introduced to Bob Powers by James Reilly. Bob is a PhD candidate in Philosophy at Marquette University and an adjunct professor at Concordia University in Wisconsin.

Bob was incredibly generous with his time. After reviewing my lecture, and discussing the subject matter with me—over the course of a three hour phone call—he encouraged me to continue to pursue this vein of research. This paper is the result of that encouragement, and many of the papers cited in this article were shared with me by Mr. Powers. I’m eternally in his debt.

Background and Historical Context:

Unfortunately we don’t know a lot about Angelo Viggiani’s life. We know that he was Bolognese in origin and born sometime in the late 15th to early 16th century. It’s possible that he and his brother Battista were the son’s of Giasone Viggiani.1 The Viggiani family {Vizzani} were one of the oldest noble families in Bologna, and through much of the 14th-15th century were associated with the ruling Bentivogleschi faction. However, in 1449 they participated in a coup, led by the Fantuzzi and Pepoli families, and were exiled from the city. Later, in 1506 after Pope Julius II overthrew the Bentivoglio family, many of the exiled patricians were given an opportunity to return to the city; including members of the Viggiani family.

Among the notable members of ancient Vizzani lineage, probably the most resplendent is Melchiore Vizzani: famed knight, diplomat, and politician. In 1445 Spezza Vizzani stood shoulder to shoulder with Bologna’s greatest patrician, Galeazzo Marescotti d’Calvi, and defeated a number of Caneschi marauders with sword and targone. Nanne Vizzani, the son of Melchiore, was the member of the lineage who made the fateful decision to align the family with the Pepoli and Fantuzzi in 1449.

Returning to our subject: upon being repatriated to Bologna, Angelo followed in the Ghibelline heritage of his ancestors and became a cavalry captain in the Imperial Army. He served the distinguished commander Ferrante Gonzaga, who was, “{Charles V’s} foremost general and personal friend,” (Armstrong, pg. 271) and seems to have taken part in the siege of Florence in 1529.2 It is likely through Angelo Viggiani’s relationship with Ferrante that he became acquainted with his muse, Luigi Rodomonte Gonzaga, and the Holy Roman Emperor, his future patron.

In 1530, when Charles V was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII in Bologna, Angelo Viggiani del Montone was a member of the Imperial retinue. Charles V was quite fond of Bologna, and returned to the city in 1533 after defeating an Ottoman army in Hungary. While in Bologna, he was delighted to take part in the annual Carnivale festivities, and competed with his dear friend Don Ferrante Gonzaga in combat at the barrier with spear and sword.

When the time of Carnival arrived, numerous games and festivities were organized throughout the City to entertain the Lords and gentlemen of the Court. Notably, some tournaments took place in the palace, one of which featured Emperor Charles, who wished to engage in combat with Don Ferrante Gonzaga using a pike and a stucco. In this contest, both participants, clad in shining armor, displayed remarkable skill and boldness, much to the delight of the Princes and the other attendees.

—Vizzani, pg. 6 (1533)

In his personal life, the emperor was a patron of numerous fencing guilds and shooting clubs, and enjoyed participating in their sanctioned events whenever time would allow. Among his courtiers were a number of prominent and notable figures in fencing history, and two of Viggiani’s eventual muses, including: Albrecht Dürer, Don Luis Fernández de Córdoba y Zúñiga (Manciolino’s patron), Luigi ‘Rodomonte’ Gonzaga (Viggiani’s muse), and Johann IV Count of Egmont (Viggiani’s muse).

Unto Viggiani’s third voice in his dialogue, Ludovico Boccadiferro, we can ascribe a fairly similar story. Angelo and Ludovico were certainly contemporaries, unfortunately it's hard to tell where exactly they may have met—if at all—or what influence they had on one another without more biographical detail. That said, there’s a tangled web of threads where both men’s lives overlap, and it is beneath this warp that we can find plenty of opportunity for their acquaintance.

Boccadiferro was one of the great lecturers in Philosophy at the Università di Bologna. He was also a contemporary and acquaintance to many of the members of the Academia del Viridario, of which Viggiani may have been a member. This scholarly society was founded by Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, whose brother, Alessandro Achillini, was Boccadiferro's greatest influence and principal instructor in Philosophy and Medicine. Both Giovanni Filoteo and Alessandro were courtiers in the Bentivoglio court, and if not Marozzo, certainly spent time with his patron Guido II Rangoni; one of Viggiani’s stalwarts of fencing. Giovanni, in his 1504/1513 work, Viridario, included sword and small buckler fencing, at the mezza spada (half sword), as one of the key facets of his ‘garden of the mind'.

It’s my belief that Viggiani’s lo Schermo is a product of his time in the Academia del Viridario, whose principle aim was a recreation of the fertile grounds that produced so many great Bentivogleschi courtiers, by combining scholasticism with the principles of chivalry—a theme in books one and two of Viggiani’s work, and the core tenant of Achillini’s epic poem. Unfortunately no concrete evidence of this has come to light.

Of the scholarly Academies that arose in the early 16th century, Ludovico Boccadiferro was notably a member of the Accademia Bocchiana along with Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, Alessandro Manzoli, Claudio Lambertini, Leonardo Alberti, it’s founder Achille Bocchi, and Romolo Amaseo; many of whom were also members of the Academia del Viridario.3

Beyond the court life of Bologna, Ludovico Boccadiferro was a close friend of Cardinal Pirro Gonzaga, the younger brother of Luigi Rodomonte Gonzaga. Pirro encouraged Boccadiferro to come to Rome and teach at the university of Sapienza, in 1525 after the professor had a dispute with Alessandro Achillini’s replacement at the Università di Bologna and rival philosopher, Pietro Pompanazzi.4 Ludovico would remain in Rome until the great sack in 1527, which saw wanton destruction by a rogue army of Charles V; an event instigated by Manciolino’s patron Don Luis Fernández de Córdoba y Zúñiga and Luigi Rodomonte Gonzaga’s in-laws the Colonna. During the chaos, Luigi Rodomonte Gonzaga would go on to save the life of Clement VII, and in kind the Pope made his brother—only 22 at the time—a Cardinal of the Holy Mother Church.

Another exemplar of fencing heralded by Viggiani is Conte Ugo Pepoli, who’s Palazzo provides the setting for Viggiani’s dialogue. Despite Ugo and the Pepoli family’s predilection toward the Guelf faction; representing those who aligned themselves with the kingdom of France in this time period5, Rodomonte—a staunch Ghibelline—holds a fondness and deep respect for the storied captain. This is likely Viggiani justifying his own feelings on the matter, and incorporating an appreciation for his families ancestral allies despite their political differences. It’s worth noting that Viggiani’s third voice in the dialogue, Conte de Agomonte (Johann IV Count of Egmont), is staying with Emilio Malvezzi; the most powerful Ghibelline family in Bologna. This is Boccadiferro and Rodomonte discussing the matter:

BOC. Where are you staying, Sir?

ROD. In the house of Count Ugo de' Pepoli

BOC. I would have rather believed, that you would be staying in the house of one of these illustrious Lords Malvezzi, since you are so Imperial, and maintain, and favor the same Imperial party in this City.

ROD. Even though I am a servant of the Empire, nevertheless I hold friendship with all the honored Knights, and I am rather in the house of Count Ugo because of the close friendship we have together.

BOC. And if I believe I can do this without offending the Count, and if I hope to obtain this from my Lord Rodomonte, I would try to force you with entreaties to make me gracious enough to stay with me, with whom you would have lodgings if not worthy of you, at least as loving as any other.

ROD. I thank you (Doctor) and it would not be honest to leave Count Ugo. I would like a favor from you, and that is that you show me your study.

—Viggiani pg. 26-27

Conte Ugo Pepoli and Conte Guido II Rangoni fought a duel in Mantua beneath the walls of Castello Gonzaga in 1516. The young, impressionable Rodomonte was 16 years-old at the time, and was a few years away from joining, the future Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V’s retinue as a courtier alongside Johann IV Count of Egmont, and Don Luis Fernández de Córdoba y Zúñiga.

Before his journey, Baldassare Castiglione, the author of the Book of the Courtier, gifted Luigi a hunting dog; a symbolic start that would see its ends fulfilled. Luigi was a model courtier, and earned his nickname Rodomonte, by defeating a giant Moor in a wrestling match. After Charles’s assent as the King of Spain, Rodomonte and Don Luis, would join the sovereign on a voyage to England to treat with Henry VIII, to subvert an alliance between France and England set to take place at the famed Field of Cloth and Gold.

On this trip, Rodomonte so impressed Henry VIII and Charles V with his hunting acumen and courtly manner, that he earned an embrace from both sovereigns. A matter that would tragically overshadow the life of Don Luis Fernández de Córdoba y Zúñiga.

Angelo Viggiani would finish his treatise titled lo Schermo in 1551; and dedicated it to Charles V, but wouldn’t live to see his work published; dying shortly thereafter. 15 years later in 1567, acting on Angelo’s will, his brother Battista would finish the publication, and rededicate the work to Charles’ successor, Maximillian II.

One of the prevailing themes throughout Angelo Viggiani’s lo Schermo is the path of the Philosopher and the path of the Soldier, where Luigi ‘Rodomonte’ Gonzaga represents the consummate soldier and Ludovico Boccadiferro represents the wizened old philosopher. Angelo Viggiani likely saw the entirety of the work—his masterpiece—as a harmony of both. Incidentally, his nephew, Enea; the son of Battista, would chose the path of the philosopher and become a lecturer at the Università di Bologna in 1576, after graduating with degrees in Philosophy and Medicine in 1572 (the two primary courses dominated by Achillini and Boccadiferro), and continued in the vocation until his death in 1602.6

Of the later notable members of the Vizzani family, few are as transcendent as the great Bolognese Chronicler, Pompeo Vizzani (1540-1607). He composed 12 books over the course of his storied life, beginning in 1578 with a retelling of the immaculate Carnivale tournament put on by the Knights of Viola in honor of his dear friend Ugo Boncompagni upon his assumption of St. Peter’s throne as Gregory XIII.

Pompeo Vizzani was a consummate statesman, serving as console in the Bolognese Government in 1558 wherein he was elevated to Gonfaloniere del Popolo, then later served as Tribuno della Plebe in 1585. Vizzani, like his forebearer, committed his life to a scholastic exploration of the classics, math, science, cosmology, and moral philosophy, while also pursuing excellence in gymnastics, fencing, and horsemanship.7 This later pursuit brought him into accord with the founders of the legacy organization of the Academia del Viridario, the Cavalieri della Viola or Desti; the famed Knights of Viola—of which Pompeo became a member after it’s inception in 1563.

Among the notable members of the Knights of Viola were Conte Pirro III Malvezzi, Marchese Ugo II Pepoli; great nephew of Conte Ugo and cousin of Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s patron Fabio Pepoli, and Pirro Boccadiferro; Ludovico’s nephew, among others. Pirro III Malvezzi, one of the founders of the Academia, had a reprint of Viggiani’s lo Schermo dedicated to him in 1588, by Zacharia Cavalcabo.

This publication was produced and redistributed by the Bolognese printer Giovanni Rossi8, who printed many of the Knights of Viola’s works, and a number of Pompeo Vizzani’s publications.

Speculative Aside: In looking into Viggiani’s family further, I’m beginning to suspect that Angelo and his brother Giovanni Battista were bastard or natural sons of Giasone Vizzani. Neither Angelo or Giovanni Battista are recorded as ‘official’ members of the Vizzani family, but Enea, Giovanni Battista’s son is; despite his father’s exclusion, and this is likely because he completed his doctorate and was recognized as noble (If this proves true it's also an indication Angelo never got his golden spurs). Contemporarily, it wasn’t uncommon for bastards to take the family name. Luigi ‘Alessio’ Pepoli was the bastard son of Guido Pepoli, and was adopted in the loving memory of his late father Guido by his uncle Giovanni Pepoli in the 1550’s. When Luigi got in trouble for trying to murder a senator of Bologna, Giovanni had to testify that—while the Pepoli let him use their name, he was not a Pepoli.

If Angelo and Battista are the bastard sons of Giasone di Domenico Vizzani, then they would be the ‘natural’ brothers of Camillo di Giasone di Domenico Vizzani, the father of Pompeo Vizzani. This relationship could explain the addition of del Montone as a moniker of extramarital progenity.

Viggiani’s Schermo: Why?

Oh, by your faith, Conte, don’t give me these bizarre names of guards of yours, please abandon calling them your code lunghe distese, your falconi, porte de ferro larghe, o strette, and such strange fantasies…

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of the philosophical underpinnings of Viggiani’s schermo, let’s look at why Viggiani decided to reimagine fencing and more importantly guard conventions in the mid-16th century:

ROD: I can; rather there are an infinity of guards, Conte, as there can be an infinity of settlements and positions; and it is true that each increment of space that you move the sword from high to low, or from low to high, from the forward to the rear, and the contrary, and from the right side to the left, and the contrary, and each little bit that you retire your foot from place to place, and in sum every infinitesimal movement forms diverse guards, which movements are without number or end. These Masters have, rather, placed names to those more necessary in order to have a way to be able to teach to their disciples with more facility, and having taken such names from some similarity or effect, from which whomever has well considered the semblances of the animals perhaps may have been able more appropriately to say “guard of the Unicorn”, “guard of the Lion”, and other such; but I, who am not a Master of a school, to you, who are not now my disciple, do not intend to give you to understand today all our exercises entirely for practice, but I will select only a schermo (as I said) with which, coming to blows with your enemy, or assaulted by him, or assaulting him, you can perfectly and preparedly strike him mortal wounds, and make a most secure defense from his. (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 23)

The biggest takeaway from this explanation is that Viggiani understood the necessity of naming guards based on their utility or effect, but disagreed with the use of colloquial and zoomorphic conventions and derided the infinitesimal volume of potential guards rendered by every minute variation, as they respectively tended to ring hollow to someone unacquainted with or developed within the system and overcomplicated the art. He wanted a way to teach fencing that clearly expressed the principles therein—we can call this the soldiers paradigm. This wasn’t a novel complaint. The anonymous author of MSS Ravenna M-345/M-346, states:

And so because we have taught and given the knowledge of the gallant guards that pertain to this ingenious art of defense, because there is no other thing in this art that you may need to understand as much, so that when you find yourself against an enemy, you can immediately identify how he keeps his sword, the placement being from the infinite and innumerable ends of the various attacks and modes that vary from that guard to another; and so you will know what is suitable because being very shrewd and illuminated with the knowledge of his placement you will make effective attacks, with tempo, and with the sword, and the body; and doing them in such a manner that you will remain secure from harm.

Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus, pg. 6

What the anonymous author is purporting here, is exactly what Viggiani wishes to solve. A statement of importance; because there is no other thing in this art that you may need to understand as much, followed by an objective; you {should} immediately identify how he keeps his sword, a problem; the placement being from the infinite and innumerable, and a solution; know what it is suitable because being very shrewd and illuminated with the knowledge of his placement you will make effective attacks, with tempo, and with the sword, and the body; and doing them in such a manner that you will remain secure from harm.

To actualize this and reduce the guards, cuts and thrusts down to their base principles—to garner the knowledge to make effective attacks—Viggiani renamed them. To further understand how he decided on the specifics of his new naming convention, we have to start at the end.

BOC: If our Aristotle entirely reduces the ten {predicamenta}9 under two headings, “substance” and “accident”, or, we wish to say better, under “action” and under “potentiality”, as each thing will be either an action or a potentiality, similarly does the unvanquished Rodomonte reduce under these two headings all his art: that is, under “offense”, which is action, and under “defense”, or “guard”, which is potentiality; and in taking the most perfect action and the most perfect potentiality, has therein enclosed every other inferior action, and every other inferior potentiality. (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 55)

Aristotle’s ten predicamenta that Boccadiferro is referring to here are outlined in his work, Categories, they are: 1.) Substance; 2.) Quantity; 3.) Quality; 4.) Relatives; 5.) Somewhere; 6.) Sometime: 7.) Being in a Position; 8.) Having; 9.) Acting; and 10.) Being Acted Upon. (Studtmann; Aristotles Categories) These are his ten highest kinds, or categories; as they are indefinable, and within each of these kinds there are subsets of genus and species with varying degrees of diferentia. Let’s define these terms.10

Genus (Family): A broad category that contains species, a proximate group.

Differentia: The essential defining trait; difference.

Species: A type of thing. Defined by genus and differentia.11

To illustrate this methodology, let's look at one of Aristotle’s most famous examples—man. Humans are Animals (genus) and the differentia that separates them from other animals is that they are rational, therefore the species of man is rational animal. Note that there are a number of other differentia and genus that separate man from other animals; they're bipedal, they're mamalian, etc., but the most unique differentia, the highest kind, that separates man from his fellow animals is rationality.

Through the miracles of modern science we can poke a number of holes in this rational delineation, but that wouldn't serve us in the purpose of understanding Viggiani’s work, or how he viewed Aristotle's systema. Take this as a warning to clear your mind of your biases as we move forward. What we’ve just highlighted loosely satisfies the category of substance. Now we need to discuss our accidents; ‘action’ and ‘potential’.

The Oxford reference definition of an accident is, “In Aristotelian metaphysics an accident is a property of a thing which is no part of the essence of the thing: something it could lose or have added without ceasing to be the same thing or the same substance. The accidents divide into categories: quantity, action (i.e. place in the causal order, or ability to affect things or be affected by them), quality, space, time, and relation.”

Now that we have a base understanding of the key concepts, let’s dive into Viggiani’s lo Schermo.

Logic of Viggiani’s Guards:

First we must define, what a guard is? Viggiani explains:

CON: …What do you mean by “guard”? Do you want perhaps to mean that which is meant by others?

ROD: Know you well, that lying calm and settled in some form with arms, either in order to offend or defend, that settlement, and that position, and that composition of the body in that guise, in that form, I call “guard”.

In his discussion of tempo, Viggiani also gives us a physics based definition that will be important for understanding later portions of this discussion.

ROD: I see that the Conte does not understand well; and therefore in order to give it to him perhaps to understand, speaking chivalrically: you see, Conte, the philosophers have proven that prior to a body moving itself it will remain at rest, and ceasing its motion again remains at rest; so that a motion (provided that it be single) will lie in the middle of two rests.

BOC: In the Seventh and Eighth Physics Aristotle proved it; Rodomonte speaks the truth.

…

ROD: All right, it suffices that each motion that is single and continuous lies between the preceding and subsequent rest; look, then, Conte: before you throw a mandritto, a rovescio, or a punta, you are in some guard; having finished the blow, you find yourself in another guard; that motion of throwing the blow is a tempo, because that blow is a continuous motion; thus the tempo that it accompanies is a single tempo; when you rest in guard, having finished that motion, you find yourself once again at rest; it is therefore a tempo, a motion, which instead of calling a “motion”, we call a “tempo”, because the one does not abandon the other; and the guard is the rest and the repose in some place and form. In conclusion it is as much to say “tempo” and “guard”, as it is to say “motion” and “rest”. (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 27-28)

Therefore, a guard is a point of rest {that being a point where motion ceases}, either before or after a motion. In combining these two observations we can define a guard as a settled position of rest with the potential to either offend our enemy or defend against them.

Viggiani’s logic for renaming the guards follows:

(H)ence I set only seven guards, and these in order to name them conveniently are placed according to the form and the purpose of the guard.

—Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 23

Form and purpose. A form can simply be defined as: the external shape, appearance, or configuration of an object.12 Purpose is more of an abstract concept. Dr. Michael Augros observes, “{what} Aristotle calls a σκοπός {purpose}, a mark to aim at, a goal.”13 This mark or aim would be either offense or defense as Viggiani himself explains:

I will select only a schermo (as I said) with which, coming to blows with your enemy, or assaulted by him, or assaulting him, you can perfectly and preparedly strike him mortal wounds, and make a most secure defense from his.

—Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 23

Thus our purpose (σκοπός) is to strike mortal wounds {attack; offensiva} or to make a secure defense against the same {defense; difensiva}. Viggiani confirms this by stating, “I designate offensive or difensive, according to the purpose.” (Swanger, pg. 24)

What differentiates the purpose of the guard, whether it is offensive or defensive is the guard’s position. If it is on the right, then it is offensive, if it's on the left it’s defensive.

ROD: I will tell it to you: every guard formed on the left side will be called “difensiva”, and all of those on the right side will have the name “offensiva”; accordingly any time that the sword will be found on the left side (with the right foot in front, nonetheless, which we always assume, as much in guardia larga, as in stretta), still, whether the arm be found higher, or less narrow, or lower than it between the stretta, and the larga, that will be understood as a defensive guard, and will be for defense; and all the times in which the sword will be found by the right side (also with the right foot forward) both in guardia alta perfetta and in imperfetta, both in guardia stretta and in larga, either were it then among the alta, and the stretta, or between the stretta, and the larga, provided that the sword should be by the right side, such a guard will always be understood as offensive, and will be in order to offend. This will be our rule, and hold it fixed in your memory. (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 33)

This sense of purpose informs its substance, and can therefore be further categorized as its most essential genus. It is the highest kind in Viggiani's Schermo. That means that further diferentia or genus of the guard—the accidentals—will not change the purpose or the substance.

This speciation has two more key genera, they are perfetta and imperfetta. Simply defined a perfect guard has its point on-line and an imperfect guard has its point off-line. While these two categories are accidental and don't change the purpose of the guard, they have their own subset of differentia, and are therefore a genus.

Viggiani differentiates between the two based on their potentiality. We’ve already defined a guard as a position of rest; calm and settled, with the potential to either attack or defend. What comes from said guard or position of rest is motion. As such, one can reason that it’s quality is defined by it’s potential motion or it’s Dunamis (δύναμις).

Regarding perfecta, Viggiani says:

CON: Why is it called “perfetta”?

ROD: Oh, didn’t I tell you that you need to turn the point of your sword toward my chest? Look, because it engenders the thrust, one calls it “perfetta”; but if indeed it principally engenders the thrust, nonetheless from it is easily born the {cut}…

Regarding imperfetta, Viggiani says:

CON: Why is it called “imperfetta”?

ROD: Because it does not give rise to a thrust, but only a cut, and therefore is of less offense, and I will avoid it more easily

The differentia between the two qualities are: can thrust, cannot thrust, can cut. A guard that is perfetta can both thrust and cut, while a guard that is imperfetta cannot thrust and can cut. These outcomes—derived from the potentiality of the guard—when actualized are the kinēsis (κίνησις).

To some these differentiations will seem absurd, they'll reasonably argue that from x or y point off-line guard they can still thrust. While that can be true and Viggiani acknowledges this, it lacks proper cause. That is, Aristotle differentiates between potentiality and possibility. Possibilities are predicated on a series of actions coming together to create the potentiality, where potentialities already have the necessary materials in place. To relate this back to our guards, a point on-line position has already satisfied the prerequisites for delivering a thrust, while point off-line position would require some motion of the edge (cut) to bring the point on target. Therefore, point position is the coincident, or necessary condition for the thrust.

The word that Viggiani uses here is ‘partorisce’ or ‘partorirà’, this generally translates as: to give birth to, or to be prepared to labor, or to be in the throws of childbirth, it is the potentiality not the possibility, as all the prerequisites of child rearing, term and conception have been satisfied.14 It can also be translated as: to produce in an intellectual manner—a well conceived thought—in a sardonic manner. This again satisfies the potentiality; with the prerequisite of intellectually acting as the coincidental. In modern translations of Viggiani it’s often rendered as ‘engenders’ or ‘gives rise to’ by Swanger, Leoni, Chidester, et al.

Furthermore, Viggiani clarifies that point off-line and wide guard positions; notably guardia defensiva imperfetta larga (porta di ferro larga), while being capable of the thrust, leaves the fencer too exposed, and is therefore imperfect beyond it’s potential, it’s imperfect in it’s purpose.

ROD: …Now we go to the defensive guards; either they give rise to a thrust, or a cut; if a thrust, they are called “perfect”, and have a single type which we call “difensiva, perfetta, stretta”. If they give rise to a cut, it will either be wide, or less wide; if quite wide, it will be holding the sword girded at the side, and we say that it is “guardia difensiva, imperfetta”. If it is less wide, we call it “difensiva, imperfetta, larga”.

CON: Won’t this last guard give rise to a thrust? Why do you therefore want to call it “imperfetta”?

ROD: You are correct; but we call it “imperfetta” because you uncover your body too much to the enemy, and through being very wide, you can use it in other ways than in delivering a thrust.

One doesn’t need to look far in the Bolognese corpus to understand what Viggiani is referring to when he says, “in other ways than in delivering the thrust.” Achille Marozzo, Antonio Manciolino, and Giovanni dall’Agocchie all use the rising false edge from Porta di Ferro as a key function of their fencing system(s).

To conclude, the presence of the prerequisites, the coincidentals required for full potentiality and purpose, inform the perfection and imperfection of the position.

The final differentia is characteristic of form and belongs in the category of relativity. This will have a more familiar ring for the student of Bolognese fencing: Alta; high, stretta; narrow/low, larga; wide. Viggiani asserts the following, “larghe, strette, or alte, according to the form.” One could reduce these to higher than, narrow/low, and lower than or wider than. This notion, in a sense, satisfies part of Boccadiferro's observation that Rodomonte’s Schermo addresses both the most perfect potentiality and every other inferior potentiality, where a potentiality is a guard, and perfect and inferior represent the infantesimal possibilities inbetween. As differentia, these variations of position are also accidental, in that one could change the relation of the guard; alta, stretta, larga, and not change the purpose of the guard.

Thus we have a full taxonomy of seven guards: substance; offensive or defensive, genus; perfect or imperfect, and a characteristic set of differentia: alte, stretta, and larga. When combined they form seven species of guards.

ROD: The first is called “guardia difensiva, imperfetta”;

The second, “guardia alta, perfetta, offensiva”;

The third, “guardia alta, imperfetta, offensiva”;

The fourth, “guardia larga, imperfetta, difensiva”;

The fifth, “guardia stretta, perfetta, difensiva”;

The sixth, “guardia larga, imperfetta, offensiva”;

The seventh, “guardia stretta, offensiva, perfetta”

What Angelo Viggiani has accomplished with this logical erudition addresses the first half of the statement from the anonymous author, quoted above, “{S}o that when you find yourself against an enemy, you can immediately identify how he keeps his sword, the placement being from the infinite and innumerable ends of the various attacks and modes that vary from that guard to another…,” which was echoed in Rodomonte’s explanation to Conte de Agomonte that, “there can be an infinity of settlements and positions(.)”

The objective is to give the fencer a quick read on what is being communicated by their opponents guard position, while also giving them knowledge of the potentiality of the guard they hold. This account solves the problem of infinitesimal variation, by identifying the pertinent characteristics and reducing them down to their base potential. Viggiani concludes:

ROD: Behold: a man can have his arms either on the right side, or on the left side. If on the right side, it will be called an offensive guard; if on the left side, it will be called an defensive guard. The guardia offensiva, perfetta gives rise to a thrust or a cut; if it gives rise to a thrust, it will be called “offensiva perfetta”; if a cut, “offensiva imperfetta”. The guardia offensiva perfetta will either be done high or low. If it is done high, it is said to be “offensiva perfetta, alta”; if it is done low, “offensiva, perfetta, stretta”. The offensiva imperfetta will either be done high or low. If it is done high it will be called “offensiva, imperfetta, alta”; if low, “offensiva imperfetta larga”. Now we go to the defensive guards; either they give rise to a thrust, or a cut; if a thrust, they are called “perfect”, and have a single type which we call “difensiva, perfetta, stretta”. If they give rise to a cut, it will either be wide, or less wide; if quite wide, it will be holding the sword girded at the side, and we say that it is “guardia difensiva, imperfetta”. If it is less wide, we call it “difensiva, imperfetta, larga”.

Now, let’s explore how he reduces the actualization of each guards potential.

Logic of Viggiani’s kinēsis (κίνησις):

{T}he unvanquished Rodomonte reduce{d} under these two headings all his art: that is, under “offense”, which is action, and under “defense”, or “guard”, which is potentiality; and in taking the most perfect action and the most perfect potentiality, has therein enclosed every other inferior action, and every other inferior potentiality.

—Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 55

In the process of reducing the guards down to their potential to construct his schermo, Viggiani also reduced the actualization of their potential, and gave what he deemed to be the best actions from each guard position. To better understand this logical digression we first have define action:

BOC: It could additionally be said that each action is between two potentialities, and each potentiality is between two actions, because the strike, while it is being a guard, is not yet an action, it is a potentiality; then, once the blow is actually thrown, it is an action.

This is Aristotle's kinēsis. Mohan defines this in the following way, “In Aristotle’s system (Physics III 1-3), a kinēsis is an agent-initiated change that has well-defined starting and ending termini,” furthermore he states, “Kinēsis always has an agent and a patient (or thing acted upon).”

The efficacy of this agent-initiated change is determined by the form and purpose of the guard. As outlined above, Viggiani determines that point-online guard can thrust and cut, and a point off-line guard can cut. Let's take a look at how Viggiani defines his cuts and thrusts.

Of the principle attacks, Viggiani—like his predecessors Marozzo and Manciolino—reduces them down to three, they are: a mandritto; from the right, rovescio; from the left, and punta; a thrust. In the text Rodomonte and Conte de Agomonte proceed to argue in some length about this sense of nominalism. Rodomonte concedes that there are various differentia based on edge; true or false, angulation: fendente, montante, squalimbrato, tondo, and ridoppio {ascendente}, and an infinitesimal number of variations in-between, but concludes that all attacks can be reduced to those three. This should sound familiar.

After applying the same logic to the falso and fendente, the conversation continues to thrusts as well: a thrust originating from the left being a punta rovescia and a thrust coming from the right a punta dritta, low to high or high to low; punta ascendente and discendente respectively, while he defines a stocatta as starting straight and terminating either left or right, and the punta ferma as not terminating at all.

In the end he concludes that there are two families of strike; two genera: thrust and cut. The second genera is with what edge the blow is performed; false or true. The true edge cuts have differentia of angulation based on the three division of space (rising, falling, and in-between: rising; ascendente, high to low at an angle (ie. left to right or right to left); squalimbrato, left to right or right to left; tondo, and simply high to low; descendente. The family of falso follow the same logic, but add falso to their name to differentiate them. While the trust have two genera, starting with direction: left; rovescia, right; dritta, and middle stocatta; which has its own differentia: terminates either left or right or doesn't terminate at all; being ferma. The second family is based on rising; ascendente or falling; descendente. To which Rodomonte adds:

However, if you mix together these types, there are born thereof other imperfect blows, made up of these, such as mezi mandritti, tramazzoni, false feints, jabs, and plenty of other blows, reducible nonetheless to this Tree, which I now present to you for your gratification.

If that seems like a lot—it is. Conte takes this deluge of information and concedes to Rodomonte’s reduction, but rhetorically quips that by his logic there are but two strikes, a thrust and a cut; as they are the highest kind. However, Rodomonte is adamant that there are three; mandritto, rovescio, and punta. This is deceptively a key point. So let's take a moment to examine it.

The presentation of this article doesn't follow the same progression of Viggiani’s text, he demonstrates his Schermo by discussing the cuts and thrusts, advantage, tempo, guards, and concludes by presenting his Schermo. I've started with the guards, and discussed the cuts, with the express intent of highlighting something that I touched on in my previous article, nominalism in defense. Understanding the logic of Viggiani’s guards empowers the reader to understand the potentiality; Dunamis (δύναμις), purpose (σκοπός), and form of the guards. With that in mind, when we view the actualization of that and purpose—the kinēsis (κίνησις)—we better perceive an interesting determination about the expected realization of that purpose. That is, guards on the left are more apt to produce a roverso and guards on the right are more apt to produce a mandritto, just like our guards that are perfetta; point on-line, are imbued with the requisite coincidentals to actualize a thrust.

Akin to this, rovescio are attributed as defensive blows; because they originate on the left, and mandritto are attributed as offensive blows; because they originate on the right.

ROD: …“defensive”, because the rovescio is a defensive blow, originating from the left side. (pg. 42)

And…

ROD: …“Offensiva” it is, then, through being on the right side, from whence (as I have told you many times) are born all the offensive guards and blows.

What Viggiani has done is taken the universal form of the guards and their particulars, and added the predictive value of potential. In this sense it deconstructs the previously argued Okhamist nominalism; present in Marozzo eg., in order to justify its conclusion. That is, it identifies the particulars that instantiate the universals, by means of speciation, and assigns value based on potential and purpose, thus rendering a purposeful change (frequens motus), with the aim of entelechy (ἐντελέχεια); which can be defined as: to have completed the potential of or to have made perfect. Where perfection would be the satisfaction of purpose and potential.

Viggiani explores this potentiality, and assigns entelechies to each of the guards. To Prima guardia difensiva imperfetta (with the sword in the scabbard) he assigns the rovescio ascendente. His justification for this is that when drawing the sword from the scabbard, a rising rovescio will cover and the point will aim at the chest of the adversary.

From there you will have formed guardia alta, offensiva perfetta {guardia di alicorno}. It’s perfect blow is the punta sopramano offensiva; either complete or incomplete.15 There is a bit of snappy dialogue between Rodomonte and Boccadiferro that’s too juicy to pass up:

ROD: With the very same rovescio I would beat aside the blow of his sword toward the air, and toward my right side, and then settling into the said guardia alta, perfetta, et offensiva, I would thrust the readied point into his chest.

BOC: If you were quick, and he slow.

ROD: If one has understanding, then there is no need for him to already be asleep.

He advocates for this punta sopramano because it instills fear; with the point at the level of the enemies eyes, it’s fast, it can be done in one tempo, and because Vegetius said that thrusts are the best.

Similarly, one could form Guardia alta imperfetta {guardia alta}, which gives rise to a full mandritto that ends in guardia larga, difensiva, imperfetta {porta di ferro larga}. From there you should do a rovescio ritondo, which fulfills it’s purpose as a defensive blow and ends back in guardia offensiva perfetta. Then you could throw an imbroccata sopramano offensiva; which has the same turns of the body as the punta sopramano offensiva, but it ends in guardia stretta, difensiva, perfetta {porta di ferro stretta}, and he adds that a mezzo mandritto, offensivo, imperfetto from guardia alta imperfetta is another means of forming daid guard. From here Viggiani’s ideal blow is a mezo rovescio tondo; as this cut is ideal for executing his schermo, but he also discusses the punta rovescia ascendente. Due to the nature of the perfect schermo, he only mentions guardia stretta, offensiva, perfetta (coda lunga stretta) and guardia larga, offensiva, imperfetta (coda lunga larga), as the endpoint of a rovescio, and says from both guards a fencer is best suited to reset into guardia alta, offfensiva, perfetta, though they have the potential of delivering every offensive action.

Guardia Difensiva Imperfetta: rovescio ascendente

Guardia Alta Perfetta Offensiva: punta sopramano offensiva; complete -or- incomplete

Guardia Alta Imperfetta, Offensiva: full mandritto -or- mezo mandritto

Guardia Larga Imperfetta Difensiva: rovescio ritondo

Guardia Stretta Perfetta Difensiva: mezo rovescio; which ends in guardia stretta offensiva perfetta, -or- rovescio; which ends in guardia larga imperfetta offensiva, -or- punta rovescia ascendente

The Perfect Schermo

To achieve the highest kind of fencing Angelo Viggiani reduces all of the guards and cuts we’ve discussed so far down to an ideal form—his perfect schermo. Two guards, and two cuts.

To begin, Rodomonte and Conte discuss whether it is better to attack or defend, to which Rodomonte concludes that it is more noble to attack. Note, that this isn’t attacking in the sense of provocation that’s common from authors like Marozzo or Giovanni dall’Agocchie, but more akin to seizing the misura di ferire; ala Manciolino’s stringere of space, dall’Agocchie's defenses, and Capo Ferro’s seeking measure. In that, the goal is to assume and settle in your position of potential, and attack the opponent in their approach when they are most disadvantaged; due to the necessity of discommoding oneself in the process of seeking measure and the likelihood of rendering tempos of attack in said pursuit.

As this is the tactical paradigm that Viggiani perceives to be the highest order of fencing, his Perfect Schermo is adept at satisfying both an offensive and defensive potential from a position of advantage.

ROD: …I tell you that this is my schermo, composed of the most perfect offense, and of the most perfect guards that there are, namely the guardia alta, offensiva, perfetta, and the punta sopramano, offensiva, perfettissima. There you have also the rovescio tondo, a good defensive blow, and the guardia difensiva larga.

Notice that there is a disparity of hierarchy. You have a perfect guard; guardia alta offensiva perfetta, and the perfect blow; punta sopramano offensiva perfettissima, but you have an imperfect terminal guard; guardia difensiva larga, and a “good” defensive cut; rovescio tondo. Because of his established hierarchy, the rovescio tondo from guardia difensiva larga is elevated among the others, because it best facilitates a return to guardia alta offensiva perfetta and the potential punta sopramano offensiva perfettissima.

Conte challenges Rodomonte with a number of scenarios that he addresses by describing the versatility of guardia alta offensiva perfetta, and advises the incorporation of guardia stretta difensiva perfetta instead of its larga variant when you expect to be attacked.

Overall his reduction of the position to maximize it's potential; Dunamis (δύναμις), can best be perceived through the realization of that potential; kinēsis (κίνησις), and it's perfect completion; entelechy (ἐντελέχεια). Thus the focus is facilitating the punta sopramano offensiva perfettissima, which is born from the rovescio tondo, and in Viggiani’s estimation can be done in one fluid tempo. The resulting terminal, be it stretta or larga, is determined by the position or reaction of the opponent, but as accidentals don't change the purpose of the greater schermo.

Thus we can reduce his perfect shcermo in the following way:

Guardia alta offensiva perfetta > Punta sopramano offensiva (perfect/imperfect) > Guardia (larga/stretta) difensiva (imperfetta/perfetta)> Rovescio Tondo (ritondo) > Guardia alata offensiva perfetta

Conclusion: The Soldier and the Philosopher

The presentation of Viggiani’s dialogue through the voice of Ludovico Boccadiferro; a paragon of the great Bentovoglio sponsored Bolognese Philosophers, Luigi Rodomonte Gonzaga; a stalwart Italian courtier and captain, and Conte de Agomonte; a renowned Burgundian knight and member of the Order of the Golden Fleece, demonstrates the purpose of the authors work. His schermo is a union of the hardened reality of a battlefield veteran, with the scholastic logia of the philosopher, and his audience are the courtiers of the ever expansive and powerful Habsburg-led Holy Roman Empire; encompassing Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, Hungary, northern and southern Italy, and swaths of the Mediterranean.

Lo Schermo tackled the challenge of communicating a local tradition to a broader international audience. To accomplish this, Viggiani utilized the philosophical principles of Aristotle to communicate form, purpose, potential, tempo, and advantage; the core tenants that he understood instantiated the milu of fencing in a common language. His work is a masterpiece—a proof of his knowledge of scholastic wisdom, and Bolognese martial arts.

While his perfect schermo reduces the logia of the ancient art fostered by Filippo Dardi, Guido Antonio di Luca, Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, Antonio Manciolino, and Achille Marozzo before him, down to its base principles and categories, and is at times critical of its proclivities, it is a representation of the art, albeit reduced and categorized with layers of Aristotelian, Averröist, Okhamist, and Brabantian philosophical underpinnings.

To some this can be viewed as a departure. Where a work delicately modified to meet the shifting landscape present in the fencing of the day like Giovanni dall’Agocchie's, Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre, is more sentimental and pure. But even dall’Agocchie couldn’t resist co-opting Viggiani’s perfect schermo in his section titled, How to Prepare a Man for a Point of Honor in a Short Time.16

This is likely due to the respect shown for Angelo Viggiani’s masterpiece by the Knights of Viola; who purchased, reprinted, and recirculated his work in 1588, with a new dedication to one of their principles members and founders Pirro III Malvezzi; himself a stalwart Ghibelline and distinguished patrician among the noble Bolognese houses.

The philosophical underpinnings of the work are themselves a recognition of the endeavors of Alessandro Achillini, his brother Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, Ludovico Boccadiferro, and Achille Bocchi. It is, in many ways, a satisfaction of Giovanni Filoteo Achillini’s Viridario, or garden of the mind. A combination of rhetoric, philosophy, martial excellence, and chivalric ideologies. The values of the Bentivoglio court he wished to reinvent in the wake of the collapse of the Bentivoglio signoria.

Thus, in spite of its revolutionary reinvention, it is a love letter to the fertile grounds that rendered it's component parts. It's a satisfaction of the expectation of a Renaissance courtier in the form of a Perfect Schermo. A masterpiece composed by a consummate soldier and philosopher.

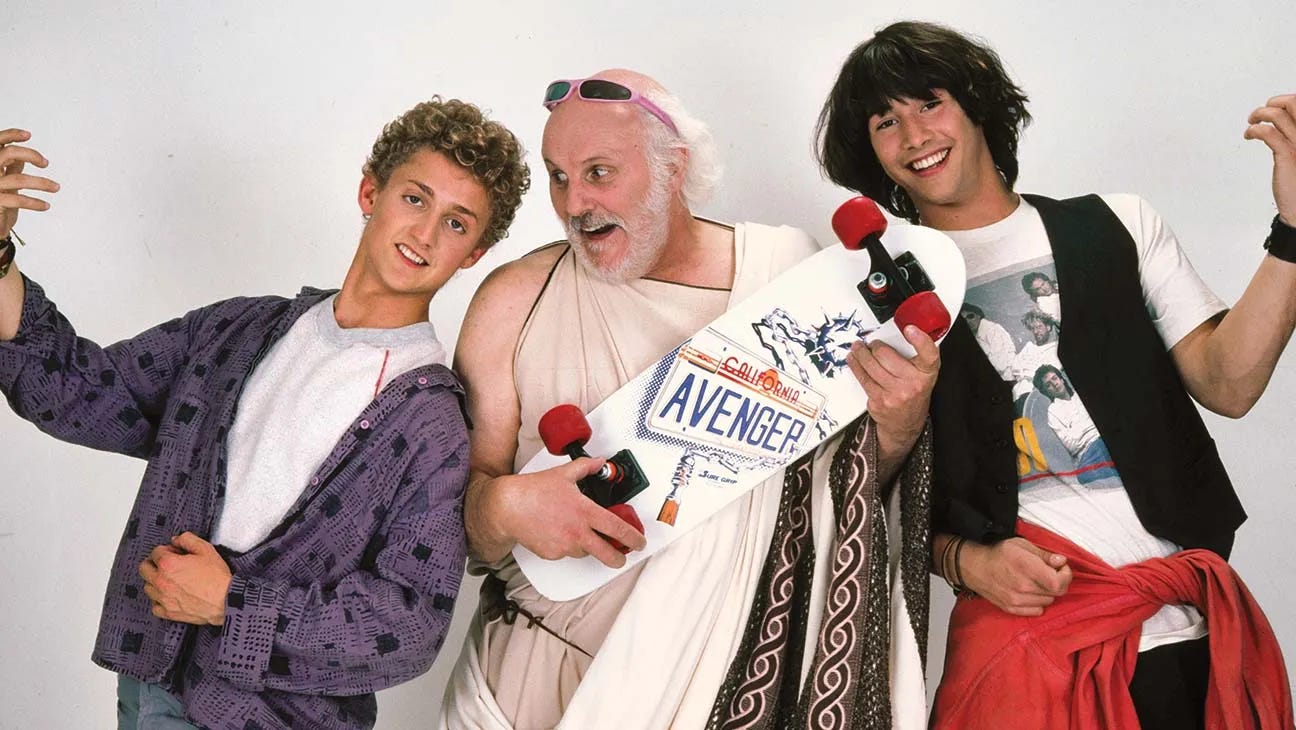

If you enjoyed this content, and would like to receive notification when new articles like this one are posted, be sure to subscribe. If you’d like to support our work with a financial contribution, you should consider a paid subscription, or click HERE, to check out our Art of Arms merch. This week we’re featuring our Angelo Viggiani collection with the masters portrait, his attack and guard trees, and the lo Schermo t-shirt; featuring Ludovico Boccadiferro and Luigi Rodomonte Gonzaga on a backdrop of Palazzo Pepoli (the location of the dialogues) with the title font from the title page of the work.

Works Cited:

Swanger, Jherek. “The Schermo of Angelo Viggiani dal Montone of Bologna.” 2002. Digital.

Fratus, Stephen. “With Malice and Cunning: Anonymous 16th Century Manuscript on Bolognese Swordsmanship.” Lulu Press. 18 February 2020. Print.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Duel, or the Flower of Arms for Single Combat, Both Offensive and Defensive, by Achille Marozzo.” Lulu Press. 22 April 2018. Print.

Leoni, Tom. “The Complete Renaissance Swordsman: Antonio Manciolino's Opera Nova (1531)” Freelance Academy Press. 27 May 2015. Print.

Swanger, Jherek. Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Dell’Arte di Scrimia, “The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation”, lulu press, May 5, 2018. Digital.

Swanger, Jherek. “How to Fight and Defend with Arms of Every Kind, by Antonio Manciolino.” Lulu Press. 4 February 2021. Print.

Fratus, Stephen. “The Monomachia: The Fencing System of Francesco Altoni.” Art of Arms Press. 1 September 2024. Print.

Termiello, Piermarco & Pendragon, Joshua. “The Art of Fencing; The Discourse of Camillo Palladini.” The Royal Armories. October 2019. Print.

Vizzani, Pompeo. Historie di Bologna: I due ultimi libri delle historie della sua patria, Volume 2. Italy, Rossi, 1608.

Giordani, Gaetano. Della venuta e dimora in Bologna del sommo Pontifice Clemente VII. per la coronazione di Carlo V. Imperatore: celebrata l'anno 1800 cronaca. Italy, Alla Volpe, 1842.

Armstrong, Edward. The Emperor Charles V. Contributor, Robarts - University of Toronto. vol. 1. London: Macmillan, 1910.

Guidicini, Giuseppe. Cose notabili della città di Bologna: ossia Storia cronologica de' suoi stabili. Italy, Tip. di G. Vitali, 1869. Digital.

Augros, Michael. ‘The Opening Line Of Aristotle’s Metaphysics.’” Thomas Aquinas College, January 26th, 2022. www.thomasaquinas.edu/news/dr-michael-augros-opening-line-aristotles-metaphysics. Accessed 3/5/2025.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Form | Definition, Nature and Examples.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 July 1998, www.britannica.com/topic/form-philosophy.

Studtmann, Paul. "Aristotle’s Categories", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2024 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2024/entries/aristotle-categories/>.

Boylan, Michael. Aristotle: Biology. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Marymount University. https://iep.utm.edu/aristotle-biology/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CHuman%E2%80%9D%20is%20the%20species%2C,between%20various%20types%20of%20animals.

Matthen, Mohan (2014). Aristotle's Theory of Potentiality. In John P. Lizza, Potentiality: Metaphysical and Bioethical Dimensions. Baltimore: Jhu Press. pp. 29-48.

Smith, Robin, "Aristotle’s Logic", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2022/entries/aristotle-logic/>

Gill, Mary Louise. Definitions in Greek Philosophy; Division and Definition in Plato’s Sophist and Statesman. Oxford Scholarship Online, September 2010.

Rotondò, Antonio. BOCCADIFERRO, Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 11 (1969). Treccani.it. Web.

Niccoli, Ottavia. VIZZANI, Pompeo; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 100 (2020). Treccani.it. Web.

Tamalio, Raffaele. GONZAGA, Luigi; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 57 (2001). Treccani.it. Web.

Mazzetti, Serafino. Repertory of all the ancient and modern Professors of the famous University, and of the famous Institute of Sciences of Bologna. St Thomas Aquinas Press, 1847. Digitized 8/31/2018. Digital. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=JO65z7Al_uYC&pg=GBS.PA322&hl=en_GB

Guidicini; Origine Bologa, Casette di Sant’Andrea degli Ansaldi.

1549 6 aprile. Luigi del fu Cesare Asinelli o Zannoni vende a Giovanni Battista del fu Jasone Vizzani una casa sotto S. Andrea degli Ansaldi presso via pubblica a mezzodì, altra strada a settentrione, Fantuzzi a sera e a mattina, per lire 2000. Rogito Francesco Coltelli. Deve essere presso la casa Gavazzi.

Giordani, pg. 64

The religious ceremonies at the onset of the new year were succeeded by various experiments and demonstrations of martial valor. In the grand square and beyond the walls of Bologna, the illustrious Dukes, either under the banner of Charles V or in the service of Clement VII, were frequently observed showcasing their bravery through vigorous combats and chivalric deeds. This provided a most captivating spectacle for the citizens of Bologna, who had always excelled in martial prowess. During this period, many of our men undoubtedly proved to be valiant soldiers, including Andrea Bovi, who served as lieutenant to Ferrante Gonzaga during the siege of Florence. Also fighting valiantly were Ercole Bentivoglio, son of Annibale II, who, during his country's exile, sought refuge in Ferrara and gained renown as a cultivator of letters and poetry. Teodoro Poeti was likewise a distinguished leader of the Emperor's cavalry and infantry in numerous military encounters, as were imperial captains Bartolomeo Campeggi, the knight Alberto Augelelli, Angel Vizzani del Montone, and Colonel Sforza Marescotti. A lengthy discourse could be dedicated to the illustrious Francesco de' Marchi, who, during those times of warfare, not only distinguished himself as a courageous captain but also earned acclaim in the mechanical arts and military architecture, surpassing the notable reputations of Lauro Gorgieri from Sant'Angelo in Vado, Francesco Luci from Castel Durante, Francesco Ferretti from Ancona, and Frauceschino Marchetti degli Angelini from Sinigaglia. Undoubtedly, the aforementioned warriors and others from our city who distinguished themselves during that era could be compared to many renowned figures from foreign lands, although they did not attain the level of fame that their glorious actions undoubtedly warranted.

Rotondò; Ludovico Boccadiferro, Treccani.it

Amico di Achille Bocchi, partecipava autorevolmente alle libere discussioni che si svolgevano nella cerchia di dotti che più tardi costituiranno l'"Accademia Bocchiana": Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, Alessandro Manzoli., Claudio Lambertini, Leandro Alberti, Romolo Amaseo.

Rotondò; Ludovico Boccadiferro, Treccani.it

Con molta probabilità il B. cedette alle insistenze dell'amico Pirro Gonzaga.A Roma insegnò filosofia alla Sapienza fino al 1527, con un successo che oltrepassava i confini dello Studio e gli guadagnava stima e ammirazione di prelati e dello stesso pontefice. A questi anni romani risalgono i vincoli di devozione che più tardi lo legheranno a Clemente VII e a Paolo III. Nel 1527, in seguito al sacco e all'occupazione della città, ritornò a Bologna, dove riprese l'insegnamento di filosofia ordinaria, che tenne ininterrottamente fino al 1545.

Armstrong, pg. 133

The foreign invasions had given a new meaning and a fresh violence to these long-lived factions. The Guelphs were now the French, the Ghibelline the Spanish or Imperial party. The survival of these factions intensified the dissension, not only of Italy, but of her several states and towns, for all local or family quarrels became sooner or later merged therein. The history of most towns in the Papal states during the first half of the century proves how much of the energy of the population was exhausted in this feud, which was a source of weakness even in cities under the stronger rule of Milan and Venice. Every Italian theoretically wished for the expulsion of the foreigner; the barbarian dominion, in Machiavelli's words, stank in the nostrils of all.

Mazzetti, pg. 322.

3140. VIZZANI Enea figlio di Gio . Battista , Nobile di Bologna , laureato in Filosofia , e Medicina li 5 Febbraro 1572 , e non nel 1575 come accenna il Conte Fantuzzi , ed ascritto ai Col- legii di amendue quelle facoltà li 29 Novembre 1576 Nell ' Anno 1574 ebbe una Lettura di Logica , che tenne sino al 1576 , in cui passò a leggere la Filo- sofia sino al 1578 , nel qual Anno venne fatto Professore di Medicina Teorica , indi di Medicina Pratica , ed in ultimo tornò ad insegnare la Medicina teorica sino al 4 Ottobre 1602 , epoca di sua morte avvenuta in Bologna . Fu sog- getto rinomatissimo , ed in grandissima stima de ' Letterati del suo tempo . = Fantuzzi Tom . VIII , p . 199

Niccoli; Pompeo Vizzani, Treccani.it

Morto il padre già nel 1541, fu affidato alle cure della madre, e si avviò agli studi delle lingue classiche e di quelle moderne (spagnolo e francese), delle scienze matematiche, della cosmografia e della filosofia morale, senza trascurare gli esercizi ginnici, la scherma e l’equitazione, in funzione di una formazione degna di un gentiluomo.

Giovanni Rossi was originally from Venice but moved to Bologna in 1559.

This is perhaps better translated as predicate, given the context, but I have reverted it back to its native Latin, to avoid any unnecessary editorializing.

Boylan, Subheading 6.

According to Aristotle, the best way to create a definition is to find the proximate group in which the type of thing resides. For example, humans are a type of thing (species) and their proximate group is animal (or blooded animal). The proximate group is called thegenus. Thus the genus is a larger group of which the species is merely one proper subset. What marks off that particular species as unique? This is the differentia or the essential defining trait.

Studtmann; 2.1 General Discussion

In fact, the essence of any species, according to Aristotle, consists in its genus and the differentia that together with that genus defines the species.

Encyclopedia Britannica: Form

(F)orm, the external shape, appearance, or configuration of an object, in contradistinction to the matter of which it is composed; in Aristotelian metaphysics, the active, determining principle of a thing as distinguished from matter, the potential principle.

Augros; Aristotle’s Metaphysics, digital.

Well, then, what sorts of things does the human soul naturally need to hear in a first introduction to a new part of philosophy? Since reason acts for an end, it needs to know first of all what it is aiming at in its learning, which means grasping at the outset the general nature of that part of philosophy it is about to learn, and how it differs from other parts. To do this is to give the learner what Aristotle calls a σκοπός, a mark to aim at, a goal. In particular, then, it is the main business of a first introduction to wisdom to give listeners or readers a preliminary grasp of the nature of wisdom, one sufficient to enable students to follow the teacher into wisdom. Accordingly, Aristotle devotes the first two chapters of his Metaphysics to explaining in a preliminary manner the nature of wisdom, and ends Chapter 2 saying “We have stated, then, what is the nature of the science we are seeking, and what is the goal which our investigation and our entire methodical inquiry must reach.”

https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/partorire/

Complete denotes that the thrust is fully extended, then pulled through to guardia difensiva imperfetta larga (porta di ferro larga), while incomplete indicates that the withdraw of the thrust ends with the guard at the knee in guardia difensiva perfetta stretta (porta di ferro stretta).

Giovanni dall’Agocchie; Swanger, pg. 36-37

Lep. I believe it, because when one loses spirit, one consequently loses art as well. But tell me, if there were someone who had to settle a point of honor and owing to shortnessof time couldn’t acquire full knowledge of the art, what course would you hold to be good?

Gio. I would train him in only one guard, and would make him always parry with the true edge of the sword and strike with a thrust.

Lep. And what guard would you train him in?

Gio. In porta di ferro stretta, followed then by guardia d’alicorno with the right foot forward; because even as all blows have their beginning in a guard, and then finish in another, this couldn’t be done without doing so either, given that one can’t throw an overhand thrust that doesn’t begin in the said guard and end in porta di ferro; and for this reason that one’s necessary, as well.

Lep. Why have you chosen porta di ferro?

Gio. For two reasons: one is that you almost never have to defend except on your right side. The other is that from this guard arise a great defense and a great offense, since one can defend oneself with a riverso from every blow that the enemy can throw, and harm him with an overhand thrust. And just as the parry with a riverso is stronger and easier, so is wounding with an overhand thrust deadlier and harder to defend against. And these are the reasons why I selected this guard.