During the Renaissance, there were moments when the condottieri became true masters of their own destinies—times when they fought personal battles for gold, glory, or vengeance; when their names echoed loudly in the chronicles and stories whispered from one town to another. Yet, there were also times when these warriors found themselves caught in history's immense and merciless currents, tossed helplessly by waves of fortune and misfortune. In these moments, individual heroics faded like single voices lost in a chorus, and life or death became a gamble ruled as much by luck as skill.

Such was the fate that carried Guido Rangoni into the city of Padua on August 24th, 1509. His arrival owed as much to fortune as to his skill, for Padua and its surroundings swarmed with enemies—the enemies of Venice, and thus now Guido's own enemies.

In that summer of 1509, vast armies from Germany, France, Spain, and the Papal States descended upon the Republic of Venice. It was perhaps the largest military force seen in Italy since the Roman Empire, with estimates soaring as high as sixty thousand troops. Historical records document at least 10,000 cavalrymen alone. All these forces converged on Padua, a fortified city situated just 20 miles (35 km) from Venice itself. Capturing Padua would mean opening the path to attack the floating city of Venice itself and to the almost certain destruction of the Republic.

Venice understood the stakes clearly. Reeling from a disastrous defeat mere months earlier, the Republic hastily rebuilt its army, pouring every available soldier into Padua. The Doge of Venice, head of state, even sent his two sons to defend the city.

Venice was going all in.

Meticulous records of the time enumerate the garrison defending the city:

555 Men-at-Arms

822 Mounted Crossbowmen (including Guido Rangoni’s company)

952 Strattioti (Greek and Albanian Light Cavalry)

5,600 Venetian infantry under arms (Civilian Volunteers)

5,100 mercenary infantry (non-Venetian)

2,000 new recruits (mostly mainland Venetian citizens, including those from Padua itself)

Padua’s fortified walls stretched a formidable 6.7 miles (11 km.) Through extraordinary effort and frantic recruitment, Venice provided enough manpower to guard these extensive defenses. True, many defenders were inexperienced—fresh recruits—unaccustomed to the brutal trials of combat. Yet, with walls beneath their feet and no room for retreat, even untrained civilians could be transformed into useful, if not formidable warriors.

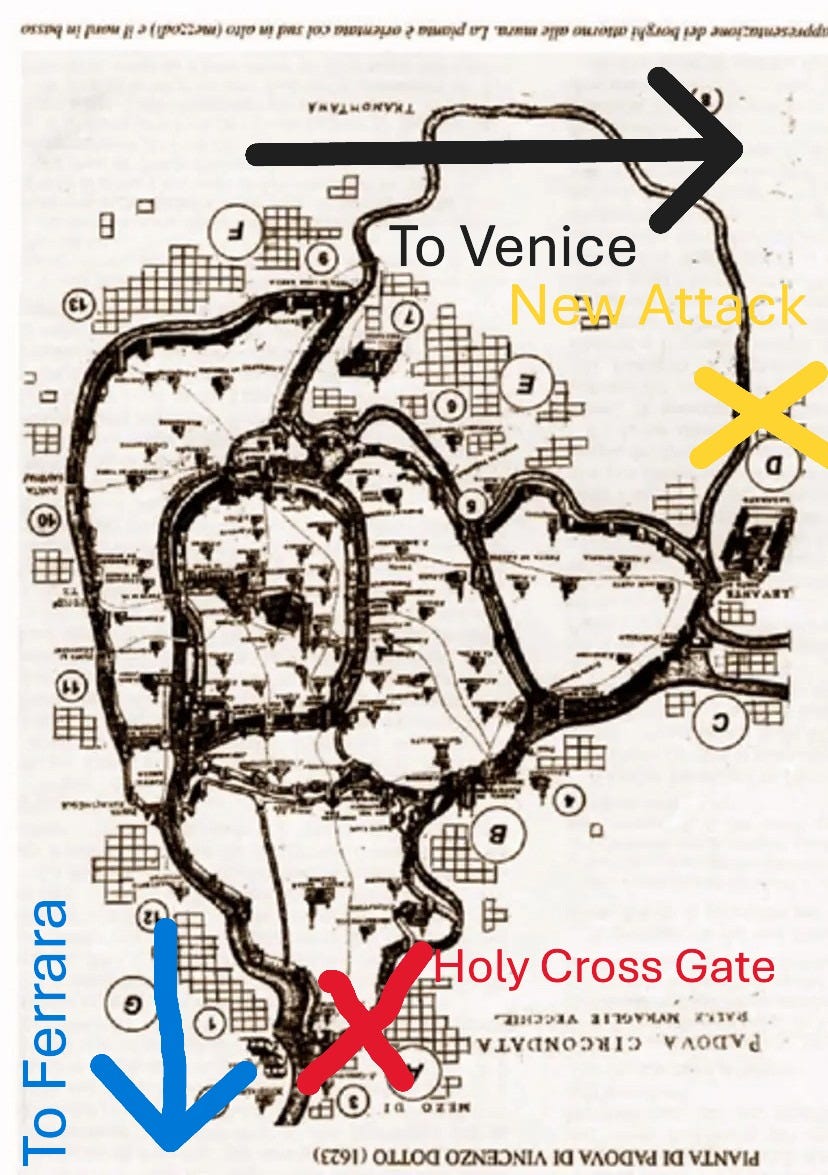

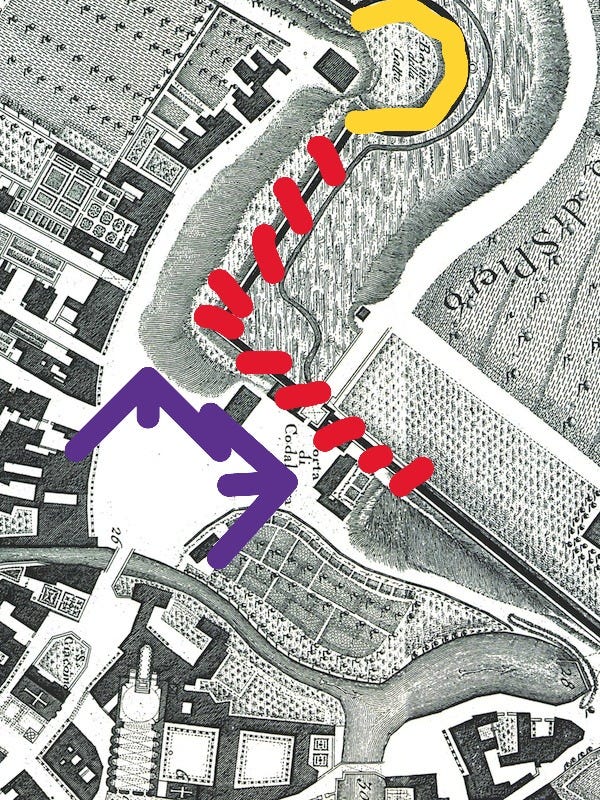

Guido Rangoni’s company of mounted crossbowmen took their station at the Prato del Valle, Padua’s expansive open ground known for hosting jousts and celebrations. From there, Guido was strategically positioned to reinforce actions near the Holy Cross gate, destined to become a fierce focal point in the early days of battle.

The morning following Guido’s arrival, the Prato del Valle hosted an inspiring display as all infantry and their artillery assembled to boost morale. The Venetians eagerly anticipated that “...it will be a splendid sight, as we have about 10,000 infantry in total, according to the muster rolls.” [1]

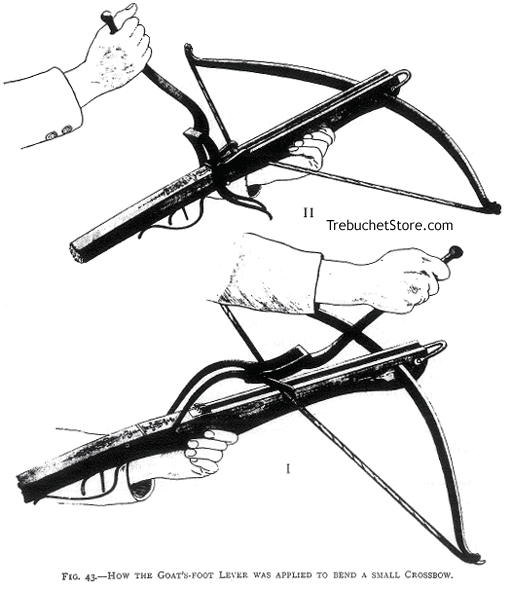

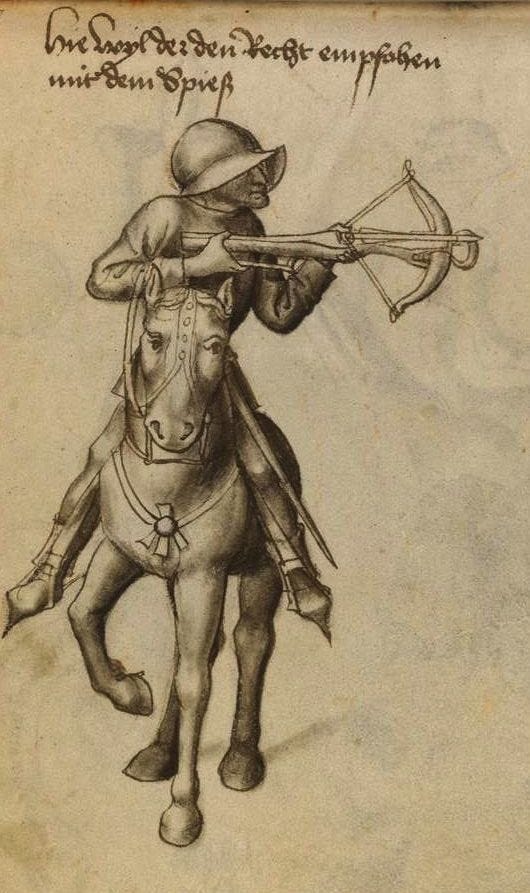

With his company hastily assembled, Guido found in this spacious terrain the necessary room for rigorous drills. Crucially, mounted crossbowmen required intensive practice—not merely to ride and shoot, but to reload crossbows from the unstable perch of a bouncing saddle. Among various crossbow designs of the Sixteenth Century, the goat’s foot lever crossbow stood out prominently. This particular type "was carried by the mounted crossbowmen in preference to any other kind of lever."[2] The goat’s foot was easy to use and easy to reload in a saddle and simple to maintain. Its only drawback was its limited power.

A more powerful but less common alternative was the Cranequin crossbow, with its intricate ratchet mechanism. This weapon could match infantry crossbows in power, was often sufficient to penetrate heavy armor at safe distances and could be reloaded in a saddle, if slowly. These were expensive and could require the work of a specialist to maintain. [3] To pierce armor reliably, crossbowmen required carefully designed bolts with four pointed corners, onstensibly to prevent the armor's curves from deflecting the shot. Historical accounts mention several bolt varieties: “common,” “large,” “olive leaf,” “half-moon,” “pointed,” and “spiked.” [4] Guido had to ensure his men were proficient with their weapons that he had the various types of bolts that would be needed.

The position of his company on the Prato del Valle put them in position to support the Venetian defenses on the south side of the city – right where the Emperor planned to make his main attack.

Big Guns

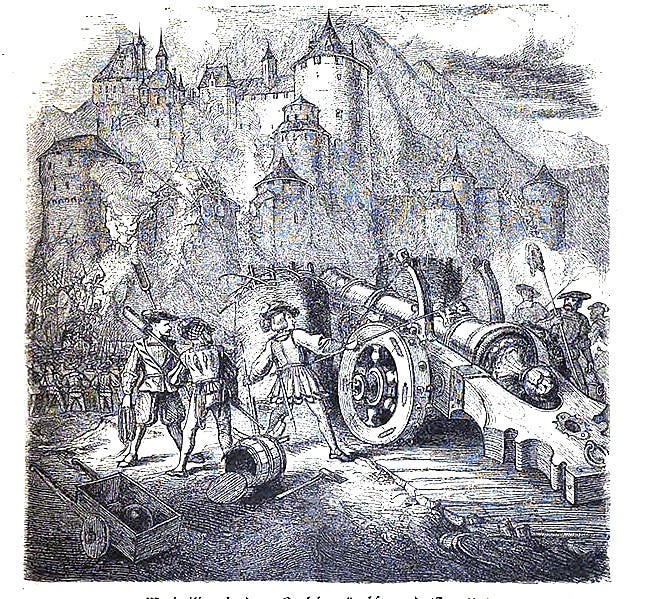

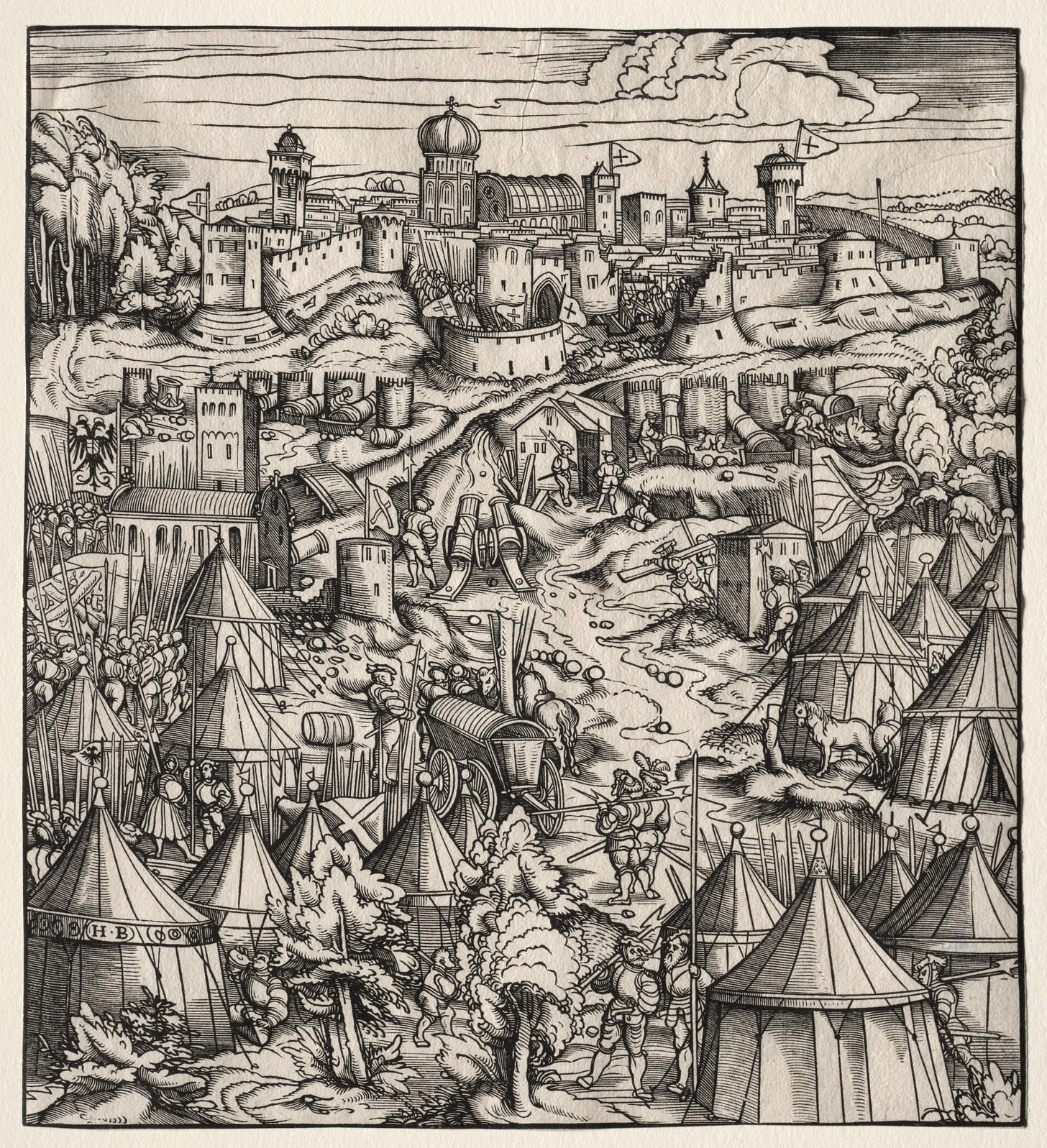

The story of warfare is a relentless struggle, a fierce ebb and flow between offense and defense. By 1509, offense had decisively seized the advantage. Ever since the French thundered into Italy with their revolutionary siege artillery, ancient walls and impregnable castles had been reduced to rubble. For centuries, towering walls, deep moats, and interlocking fortresses had safeguarded Italian cities, turning them into fortresses seemingly immune to assault. But now, the roar of cannons shattered defenses that had stood for generations. Where once sieges dragged painfully on for months, even years, these monstrous new cannons could reduce fortifications to ruin within mere days, sometimes hours.

Emperor Maximilian harbored a particular passion for these devastating guns. He commissioned German foundries to produce some of the mightiest artillery the world had yet seen, even immortalizing them in lavishly illustrated volumes—a veritable homage to his obsession with their destructive beauty.[5] But now, as Maximilian laid siege to the proud city of Padua, he would put his formidable arsenal to a more direct and violent use.

Determined to pulverize Padua's walls into dust, "No Money Max," as he was mockingly known by foes, marched a hundred of his monstrous guns across the Alps. Among them were titans like the “Main Gun Leo,” whose barrel stretched an astonishing 600 millimeters wide, capable of hurling stone balls with earth-shattering force. Equally terrifying were cannons firing iron balls—bearing grimly poetic names like "Wake Up Call" and "Purlepaus."[6]

These guns fired with such force that their report could be heard in Venice some 25 miles (40 km) away.

Recognizing the mortal threat posed by Maximilian's artillery, the Venetians struck swiftly. Just two days after Guido's arrival in the city, the Venetian garrison dispatched Johnny the Greek, a seasoned warrior, tasked with neutralizing the deadly artillery. Fierce combat erupted as the Venetians clashed with the cannon's extensive German escort. Despite capturing and defeating many escort troops, the Venetians could not seize the cannons themselves, which were withdrawn safely.[7] But the precious delay allowed Padua's defenders vital days to strengthen their fortifications.[8]

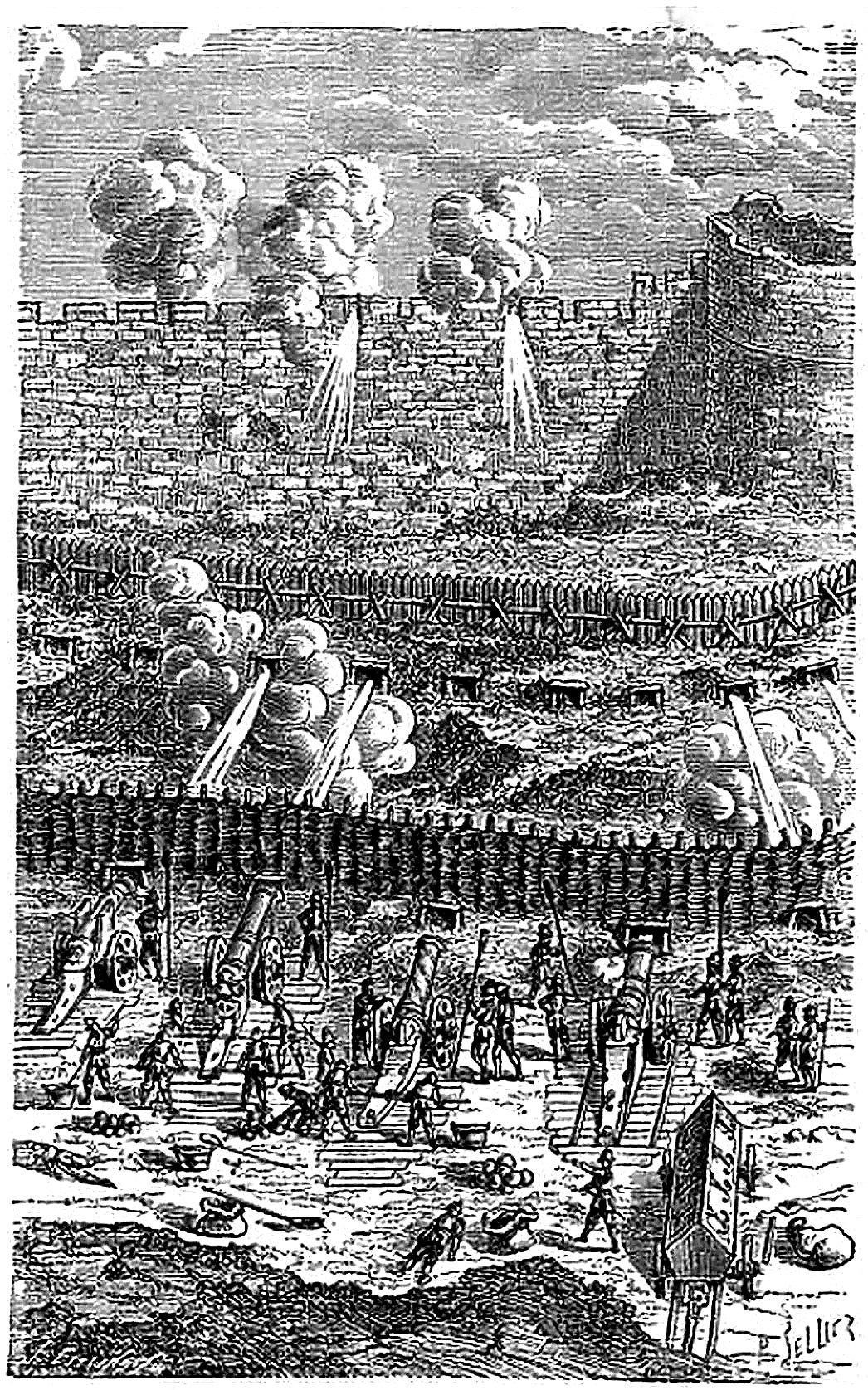

Undeterred, Maximilian regrouped, assembling an overwhelming force—2,000 cavalry and 4,000 infantry—to finally deploy his cannons south of Padua near the Holy Cross gate. This would be the focal point of his decisive assault.[9]

Near the gate stood the Venetian commander Guido's men, stationed at the strategic Prato del Valle. Initially tasked with harassing raids and as a reserve, they were rapidly thrust into combat as enemy forces surged toward the city, crossbows hissing through the air.

Maximilian planned to position his artillery among the ruined outskirts south of the gate, hoping the wreckage would shelter his precious cannons from Venetian counter-fire. But the Venetians anticipated this and hastily erected formidable barriers to blunt the imperial advance.

To carve a path for his cannons, Maximilian summoned his French allies into the fiery breach. Under the relentless blaze of the midday sun and the furious barrage of Paduan artillery, the French surged forward. A contemporary French soldier vividly described the chaos:

“At noon, beneath a blazing sun, along a causeway swept by Paduan artillery, Bayard advanced with both infantry and cavalry... crossbow bolts rained down mercilessly as they seized the first and second barricades. The third fell without a fight. But the fourth barrier, manned by twelve hundred men and four formidable cannons, stubbornly halted their momentum. An hour-long melee erupted—pikes clashed, halberds hacked, and men grappled in desperation.”

Reinforcements poured in for the defenders, and the barricade stood defiant. Recognizing a decisive push was required, Bayard rallied his noblemen with passionate fury: “Gentlemen, these defenders delay us too long; we’ll dismount and storm that barrier!”

Forty armored knights, led by Bayard and the Prince of Anhalt, dismounted, visors raised, eyes blazing with resolve. Like a relentless wave of steel, they crashed upon the enemy lines. Yet the defenders, ranks deep, repulsed them again. Amid the desperate struggle, Bayard thundered: “My lords, they'll hold us here forever if we don't strike now! Trumpeters, sound the charge!”

Summoning every ounce of strength, the attackers thrust the defenders back just enough. “Forward, companions!” Bayard roared, and with astonishing vigor, vaulted the barricade despite the crushing weight of his armor. A triumphant shout arose—“France! Empire!”—as inspired soldiers surged forward behind him. The barrier shattered, resistance collapsed, and by nightfall, Maximilian’s dreaded cannons were entrenched, ready to unleash their devastating power upon Padua’s besieged walls.[10]

To raise the spirits of his own men and to demonstrate to the garrison of Padua just how futile resistance was, Maximillian ordered a review of his massive army, while “ “dressed in full armor … his horse clad in head and breast cuirass with a black silk caparison embroidered in gold. The emperor didn’t wear his helmet, but a black French bonnet with a long white feather and gold ornaments. The young horsemen following the emperor brandished a hughe white flag bearing the image of St. George, and with a black eagle set in the tall plumes of his helmet also provoked admiring comments.” 1

Under the Guns

The relentless thunder of cannon fire echoed over Padua, but even this savage symphony had its Achilles' heel—ammunition. In the siege warfare of the 16th century, gunpowder was devoured with insatiable hunger, and Emperor Maximilian’s monstrous artillery consumed it faster than it could be supplied. This insatiable need dictated the emperor’s strategy: positioning his guns on the southern flank of Padua, near the crucial lifeline stretching to Ferrara—a city renowned for producing potent gunpowder and formidable cannons.

Yet Venice refused to sit quietly, watching their enemies replenish. The Venetians unleashed their cavalry, striking violently at the supply convoys threading their vulnerable path from Ferrara to Padua. The fierce resistance of these Venetian horsemen owed much to the countryside’s silent heroes—peasants whose loyalty provided critical intelligence and, on occasion, erupted into raw brutality. When enemy cavalry arrogantly rejected surrender, these peasants rose from hiding to "cut them to pieces,"[11] their vengeance swift and merciless.

The townspeople proved equally defiant. When German invaders arrogantly demanded the surrender of the small town of Montagnana, near Padua, its citizens cunningly opened their gates, welcoming a detachment of some thirty knights “glittering in gold.” Once trapped inside, the portcullis slammed shut with grim finality, and the invaders were slaughtered or captured—a brutal warning to all who dared threaten Venetian soil.[12] Towns like Montagnana became vital linchpins, dominating the surrounding countryside and securing Venice’s network of castles, whose lofty battlements granted unparalleled surveillance and sanctuary to Venetian cavalry caught in peril.

Yet the German and French forces pressed forward relentlessly, bombarding Padua’s Holy Cross gate daily, hurling massive stone balls against ancient masonry, while their infantry assaulted the fortresses to the south. On August 27th, Monselice fell under a storm of ruthless violence. Chronicles recall the conquerors as merciless, "worse than infidels," ravaging and desecrating everything in their path. A contingent of 500 soldiers branded as "Jewish" amplified the horror, accused of committing acts of unspeakable cruelty—slaughtering innocent children, spreading terror with chilling efficiency.[13]

Fear, as ever, proved effective. Terrified by the fate of Monselice, the fortress of Montagnana swiftly surrendered, purchasing mercy for 3,000 ducats.[14] With these fortresses crushed and the countryside pacified through brutality, Emperor Maximilian was free to unleash the full fury of his artillery against Padua itself.

The early siege became a grim duel between the colossal German cannons firing massive rounds to stave in the walls, and the nimble Venetian artillery trying to pick off the guns. Predicting the Germans’ supply line vulnerability, Venice had long anticipated the main attack would strike near the Holy Cross gate, closest to Ferrara. Their fortifications stood ready, and in those initial bloody exchanges, the Venetians gained the upper hand. Imperial bombardments achieved embarrassingly little—"knocking down a few merlons," "blasting a chimney," but failing to breach the defenses.

Even in hand-to-hand combat, the Germans fared poorly. Soldiers on both sides, driven by pride and rivalry, frequently skirmished individually or in small groups despite orders forbidding it. Eventually, German commanders, frustrated by constant losses, resorted to severe punishment. They declared that any man caught engaging in unauthorized duels with Venetians would face hanging, as the outcomes were always humiliating: “Every time they skirmish, they suffer the worst."[15]

So far the German plan was not working. The walls were holding up. The garrison’s courage was holding up … Venice was even able to row ships with fresh supplies right up to the city.

The Emperor would have to try a new tactic. Meanwhile, the siege ground on—bloody, brutal, and unresolved.

Attack on the East Side

Ten days into the grinding siege, Emperor Maximilian abruptly shifted his assault from the resilient southern walls to the more vulnerable eastern flank facing Venice itself. His strategy hinged on breaching the weaker fortifications swiftly, exploiting their fragility to crush Padua’s resistance.

But Venice was forewarned. Around September 10th, intelligence arrived in the form “a trustworthy person who left the camp came to tell them that they want to come towards Ponte Corbo and the Portello that night [gates on the east side of the city], and they want to come lightly armed to make an assault … the friend returned to the camp and will be able to tell the truth of everything better [16]

Forced to abandon their previous position in haste, the emperor's forces left behind ample supplies: grain, wine, beans, carts. The following day, starving peasants from the countryside, desperate for supplies, swarmed the abandoned camp, only to be brutally ambushed by 500 enemy cavalrymen—a merciless slaughter of innocents ensued.

Into this chaos thundered Guido Rangoni, leading his cavalry on their first major sortie from the Holy Cross gate. Bolts from his men’s crossbows rained death upon the enemy cavalry, throwing them into disarray. Amid the turmoil, his trusted lieutenant, Jimmy Manzino—a battle-hardened cousin of the slain Bentivoglio ally, Mancino da Bologna—helped coordinate a relentless assault.[17] Enemy knights struggled vainly to form ranks, their horses and armor pierced mercilessly by crossbow bolts. Soon, recognizing their imminent defeat, they retreated under the cry of trumpets. For a moment Guido made to pursue them, but the feigned retreat was a bread and butter cavalry tactic to lead an aggressive commander into an ambush, so Guido halted his eager men, gathered prisoners, and returned triumphantly to Padua with one French and one German men-at-arms as prisoners.[18]

Word spread over Guido’s attack. Casper Scappi, a former Bentivoglio rebel, now a disgruntled officer in the enemy camp, recognized this moment as his chance to change sides.[19] When Johnny the Greek led another Venetian raid, Scappi attempted surrender, mistaking them for Guido’s cavalry. But in the confusion, he was struck down, his helmet crushed by a mace. Gravely wounded yet alive, he was brought into Padua as a prisoner and informant. He was taken to see Guido and the Venetians. There he revealed critical information: Maximilian’s next move would target Padua’s poorly defended northern and northeastern walls, hoping their frailty would finally grant him victory.

Though Scappi recovered from his wounds, fate decreed his survival short-lived; two years later, he would meet his end in the a fight in Udine.[20]

Back Against the Wall

The siege had entered its critical phase. Emperor Maximilian’s forces positioned themselves strategically between Venice and Padua, severing crucial lines of supply and communication. Messengers risked their lives traveling at night, battling enemy patrols, to deliver precious information. The vital dispatch from Scappi reached Venice only after three days, the courier having “fought with enemies” to get them the message.

Venice itself trembled under threat. Enemy raids targeted their vital water supply at Lisafusina, narrowly repelled by the heroic captain Achilles from Bologna and his band of thirty courageous soldiers.[21] Anxiety spread as communication dwindled—letters stopped arriving, and the distant roar of cannon fire fell silent, prompting fearful speculation that Padua had finally succumbed.

Enemy cavalry ravaged the countryside, spreading terror and seizing hostages for ransom, even poor peasants.[22] The Venetian cavalry, now organized into larger, formidable units, fought relentlessly, intercepting convoys laden with bread and iron cannonballs bound for the enemy camp. But despite these daring efforts, the massive imperial force—some say sixty thousand strong—remained entrenched, defiant despite dwindling resources and hunger gnawing at their ranks.

Conditions inside Padua worsened. Supplies dwindled, tensions rose, and desperate pleas for money became increasingly frantic. The respectful tones previously shown by Venetian soldiers faded. Now “…they demanded money and more money, threatening harm otherwise. Those from the surrounding areas who came here [into Padua] were very insolent.”[23]

Scappi’s dire prediction proved true—the enemy discovered Padua’s weakest point, the fragile northern and northeastern walls near the Coda Lunga Gate. The Germans pounded these walls relentlessly, each thunderous strike bringing the city closer to catastrophe. Here was also the greatest concentration of Bolognese soldiers, including members of the Bentivoglio faction like Sebastian Manzino and “the mighty” Spinazzo da Bologna as well as the fiercely-named Attila da Bologna.2 They were there with over four hundred battle-hardened Bolognese infantry prepared for a desperate defense.

As German artillery battered the compromised fortifications, Venetian guns fiercely responded—one cannonball striking perilously close to the Emperor himself, forcing him to relocate his command post.[24]

Finally, the Germans concentrated their fury on a pivotal bastion near the Coda Lunga gate. After a devastating artillery assault silenced its guns, Maximilian unleashed five thousand elite Spanish infantry, promising glory and reward for victory.[25]

But Venetian commander Zitolo was ready. Under cover of darkness, he withdrew his men from the bastion, placing them instead in trenches before the bastion. As the Spanish approached, illuminated ominously by flashing cannon fire, Zitolo activated hidden firebombs. The night erupted into chaos—flames engulfed the attackers, turning their advance into a nightmare. Seizing their moment, Venetian troops surged from the trenches, swords and pikes cutting through the disoriented and terrified Spaniards.

The Spanish soldiers, brave but broken, fled in terror, leaving two hundred of their dead and dying on Padua's battered battlefield.[26]

Padua stood battered but unbowed as the siege neared its brutal climax.

Here Comes the Cavalry

Emperor Maximilian refused to relent, his determination as fierce as ever. He ordered twenty massive cannons and numerous smaller ones to unleash relentless fury upon Padua's battered walls near the Coda Lunga Gate. Behind the deafening roar of artillery, the emperor assembled the siege’s mightiest force—six thousand French and German knights, poised to storm through a jagged breach blasted twenty-five feet wide by the devastating cannonade.

Inside Padua, morale teetered dangerously near collapse. The countryside lay ravaged, the peasants unwilling to risk their lives, even with the generous offer of eight soldi per day.[27] Instead of their defiant battle cries of “Marco! Marco!”, the garrison's soldiers now bitterly shouted, “Money! Money!” [28] The urgent need for money now overshadowed everything; Venice scraped desperately, even resorting to imprisoning debtors to gather the necessary gold, some forty thousand ducats. [29]

Yet, collecting the money was merely the first hurdle. Delivering it safely across twenty perilous miles of enemy-held land seemed nearly impossible. The Venetians entrusted the daring condottiere Lucio Malvezzi, a battle-hardened warrior already famed for his audacious raids, with the critical mission. But his exploits had made him notorious among the enemy, particularly the celebrated French knight Bayard, who vowed personally to capture Malvezzi.[30]

When the treasure reached the mainland, Malvezzi boldly led a hundred men-at-arms supported by six hundred swift strattioti launching a sudden charge through weaker enemy positions west of Padua. They swiftly broke through, racing with desperate speed toward the precious gold.

In our modern era this might seem like a suicide mission, taking a large force behind enemy lines. But in a world without radios and where the closest thing to sattelite surveillance was a guy standing on the tallest tower in a castle, a large group of men on horse moving with a purpose was basically unstoppable.

Unless you knew where they were going…

The Emperor did have such a spy and soon sent his cavalry hot on Malvezzi's trail.[31]

As the Venetian cavalry commander Luigi Da Porto noted in a letter, “… he [Malvezzi] fell into a large ambush of enemy forces, who attacked with great uproar. This gave rise to a terrible skirmish between the forces, the largest that had occurred during the present siege. The enemy forces consisted of Germans and Italians, while the Venetians’ forces were Italians and Greeks.[32] Great efforts were made to protect the money, to the point where Messere Lucio himself was wounded in the face.”

“The situation turned in such a way that they found themselves surrounded by the enemy, and the fighting was so fierce on both sides that many were killed.”[33] Both sides charging with lances, the French and the Strattioti using maces in the close fight while the Venetian knights used a sword to try and cut the enemy’s reins or pierce a chink in the armor. “When the two sides clashed, both the Venetians and French charged with great force, raising so much dust that they could not distinguish each other in the midst of the battle.”[34] But the whole game was in doubt.

Even Lucius Malvezzi himself was near to being surrounded and captured.[35]

But now came—the cavalry.

Once the Venetian garrison saw the French leave they dispatched a group of mounted crossbowmen to shadow the French cavalry and make sure that Malvezzi could fulfill his mission, including Guido Rangoni’s large company.[36]

Surrounded and outnumbered, the Venetians fought fiercely but seemed on the brink of disaster. Amid the chaos, both sides charged fiercely, maces smashing against armor, swords flashing desperately as warriors fought to survive. Blinded by swirling dust and deafened by war cries, victory balanced on a razor's edge.

Just as defeat loomed, Guido Rangoni and his disciplined mounted crossbowmen thundered onto the battlefield—a timely rescue worthy of legend. Like heroic cavalry in a desperate tale, Guido’s organized volleys of crossbow bolts rained mercilessly upon the French knights, shielding Malvezzi and the Venetians as they discarded their mule train and made a desperate dash to safety.

French knights who dared to chase them met the disciplined fire of the crossbowmen. The surviving Venetians rallied behind Guido's protective barrage, retreating toward Padua, while the enemy's attention turned greedily to the abandoned mules. Yet their triumph quickly soured as they discovered Malvezzi’s cunning deception. Instead of sachels full of golden ducats—all they found were bags filled with worthless sand. The true treasure had already been carefully distributed among trusted Venetian cavalry commanders.

Thus, on September 25th, Padua triumphantly received the gold, the city’s defenders dubbing it their "Victory Funds." With renewed morale and spirits buoyed, the garrison prepared for the siege's climactic and deadliest confrontation, destined to unfold around the shattered Coda Lunga Gate.

Bastion of the Cat

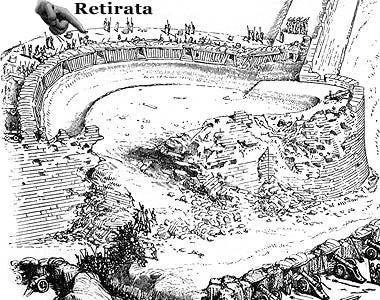

By late September, the besieging army had managed to knock down a section of the walls nearly a hundred feet in length, creating an enormous breach in the north wall. Though frenetic work by the Venetians allowed them to create a defense behind the destroyed section of wall, an earthen rampart called a “retirata.”[37]

The enemy assaulted into this area with little success. To effect a breach, they had to mass men in front of the walls of Padua. This provided an ideal target for flanking fire from the bastion which could fire lanes of death through the packed ranks before the walls.

One single cannon shot from an enemy cannon mounted on the flanks of the attack turned forty enemies into casualties.[38]

The emperor brought his attention back to the conquest of this ruined bastion.

The Venetians were aware that this was the critical part of the fight. This bastion had now become known as the “Bastion of the Cat,” because the Venetian had lacked enough banners with the Venetian lion on it to put on the bastion. The men made their own banner, but the poorly drawn figure looked like a cat instead of a lion.

This made them the subject of derision in Padua, but after the stubborn resistance of the Bastion no one was laughing at them now—the cat was now a point of pride.

The enemy now directed an enormous bombardment at the bastion striking it with 1500 projectiles in a single day and completely ruining the bastion. Many of the garrison of the bastion were decapitated by these cannonballs; heads “blown clean off.”[39] On September 26th the Emperor sent the Spanish forward again in the middle of the night. Overwhelmed by the enemy, the Spanish assault pushed back the Venetian forces away from the bastion after a short but bitter fight.

One Spanish soldier snatched the banner with the cat.

With control of the bastion the whole city was in peril. Emperor Maximilian readied a cavalry charge to take the city come the light of day.

But the commander of the bastion had one last nasty trick up his sleeve. He had prepared a fuse in the powder magazine and as the Venetians retreated, he lit it. Moments later the remains of the Bastion of the Cat exploded in a great gush of flame that killed or burned hundreds. The Venetians then sallied back towards the bastion and retook it.[40]

Now suffused with combat spirit, the Venetians surged forward from their defenses and chased the enemy back to their guns, spiked many of them and destroyed their powder.

Daybreak found the Venetians in control of the bastion once again. Since they no longer had a flag, they improvised. To taunt the enemy, they occasionally roused the cat into crying and then sang long enough for the enemy to hear:

“Up up up, who wants the cat? Come to the bastion and get it! Where she stays tied to the spear, there you see her waiting for you. Up up up who wants the cat?”[41]

While this seems cruel to us now, in a world where people were being burned alive, those without a touch of cruelty were bound to go mad.

The Landsknechts and Spaniards in the enemy camp did not want the cat anymore. They had enough of this siege.

A Supreme Effort

After a month of siege, outnumbered and battered, Padua still stood. The Lion of Venice still fluttered in the breeze over the city; beyond which, the besiegers were short on food, short on wine and short on motivation.

Still Emperor Maximilian was convinced one last supreme effort could take the city.

Had his cannons not done their job? Was his army not superior to the garrison? On the 29th of September, he called a war council with the French.

There he declared that Padua was ready to be taken. That with the great breach in the wall, that with the enemy holding the bastions and the comparatively weak retirata, only determination and skill was required to carry the city. The morale and effectiveness of his Landsknechts had waned. But the knights of France, the best and most determined fighters in the group, could tip the scales back toward the allies.

They need only needed to fight on foot beside his Landsknechts, to scramble over broken palisades and ruined bits of wall. With their courage and his Landsknechts, Padua would surely fall.

The response of the French knights came from the famous Chevalier Bayard:

“The king has no soldiers in his ordinance companies who are not gentlemen. To mix them with the foot-soldiers, who are of a lower social status would be threatening them unworthily? Does the emperor think it fitting to put so much noblesse in risk and peril by the side of conscripts, who are cobblers, blacksmiths, bankers, and laborers, and who do not hold their honor in like esteem as gentlemen?”[42]

In other words, “We’re too noble to fight amongst common foot soldiers.”

But the French were willing to be reasonable. Since they were attacking Padua for the German Emperor, if his German nobles were willing to fight on foot side by side with the French, then the French would attack into the breach.

Unfortunately for Emperor Maximilian his nobles refused to fight on foot like common soldiers.[43]

The final attack ordered by the Emperor ended in failure, to the surprise of no one. The emboldened Venetian garrison then surged forward and spiked one of the Emperor’s big mortars.[44] By this point the Emperor’s allies were leaving the camp, which had started to develop a terrible odor.[45]

Three days later Emperor Maximilian decided that the Padua was impregnable. On October 2nd, the Imperial army folded their tents, packed their gear and started a retreat from Padua and headed off for the city of Vicenza some fifteen miles away.

Venice was victorious and for once Guido Rangoni had chosen the winning side.

Editors Note

By: Joshua Wiest

The Siege of Padua was in many ways the death of Chivalry. The sportive feats of arms documented in Bayard’s biography during the siege would see their near conclusion after the final refusal of the French gendarme and German nobles to sully themselves beside the Landsknechts at the breach in the Coda Lunga gate. Both regents; Maximilian I and Louis XII, were so embarrassed by the ineffectual reality of their beholden gentry that they were forced to further reorganize their military structures.

Emperor Maximilian became more committed to the development of the Landsknechts and fraternal organizations like the famed Marxbrüder guild, while Louis XII doubled down on a controversial edict that forced his gendarme to take command of companies of conscripted and levied French infantry—a decision that would have harrowing consequences to come.

Meanwhile, in Venice the heroes of Padua were enshrined with statues and monuments; many of which can still be seen today, while Andrea Gritti became a lock to assume the role of Doge after Leonardo Loridan; a title which he assumed in 1523, and in the city of Padua—in what can only be described as some of the most epic shit talking in history—the Venetians erected a number of statues of cats high up above the streets around the Coda Lunga gate to commemorate their victory.

The world of European warfare changed after the siege of Padua. Lighter more maneuverable cannon took the field in droves, pike blocks ruled the battlespace, and light cavalry became all the rage. Amidst this tectonic landscape captains who’d cut their teeth on the opening salvos of the Italian Wars were just now coming into their own. Some of them would make their mark on history like a lighting bolt, while others would withstand the trials of these uncharted killing fields to forge a storied legacy—only for the steady procession of time to bury all of their hard-won glory beneath the trodden heels of progress.

If you want to follow our work, make sure to subscribe. It's free!

If you want to support our research financially, we’re eternally grateful, however, if a monthly subscription isn't your thing, you can also check out our webstore: Art of Arms Shop

This week's featured item is our Siege of Padua t-shirt, with Andrea Gritti’s coat of arms on the front, and the man himself storming the city of Padua on the back.

[1] This conjecture is based on information in Sanuto, including the table starting on col. 57 and the disposition on col.128. Considering the availability of the cavalry after the deadly combat after the fights at Coda Lunga we can say he was not stationed there. Lucio Malvezzi and the Captain General had other crossbow commands (Ercole Malvezzi and that of the Captain of Infantry under Malvezzi and the cavalry of Johhny the Greek and the Veronese leaders for the Captain General) that would preclude Guido’s fitting in there. No mention of mounted crossbowmen in the square with the forces under Contrairini is provided during the siege, other than to say he can get them if needed. This leave Prato del Valle by virtue of elimination.

[2] Book of the Crossbow, Ralph Payne-Gallaway, p.84.

[3] Payne-Galloway, pp.131-134.

[4] ASF, Dieci di balìa, Munizioni, 7, fols. 362r and 473r; ASF, Dieci di balìa, Debitori e creditori,

35, fol. 218v. The bolt heads were “ferri da passatoi da balestrieri a chavallo fra a foglia

d’ulivo, a punta e spuntone e lune.” From “Supplying the Army, 1498,” by Fabrizio Ansani in The Journal of Medieval Military History, 17.

[5] Note the manuscript was probably made after the siege, but that in no way negates his deep love for big bronze pipes that shot projectiles.

[7] See Sanuto, cols 97-8. Guicciardini pp 759-760.

[8] Sanuto, col.124.

[9] Storia d’Italia, Guicciardini, p.760.

[10] Shellaberger. Note this is identified as being on the northwest side of the city, but that is not where the enemy first emplaced its guns. Sanuto is clear that the first enemy firing came from near the Holy Cross Gate, on August 4th, first from trenches “where a few shots were fired.” By the next day the enemy was emplaced in the Borough of Santa Croce and firing from cover, to little effect. Sanuto, 127-128.

[11] Sanuto, col.103.

[12] Sanuto, col. 93

[13] Priuli, p.253. The identity of these as “Jewish,” is probably just Anti-Semitism in accordance with the spirit of the time. It is possible that it is related to the attacks on Jewish bankers in Padua during the Venetian capture of the city, but this is unlikely.

[14] Sanuto, col.94.

[15] Sanuto, cols. 137-138. Note this may have been a French commander and not a German. It may have even been an Italian. We only know that it was a commander in the besieging army.

[16] Sanuto, col. 151.

[17] This is suppositional. Giacomo Manzino the Paduan was among those who left Bologna in the company of the Bentivoglio in November of 1506 (see Ghiradacci p. 1506). The father of Mancino da Bologna and Sebastian Mancino was one Domenico da Padova (see www.condottierediventura entry for “Mancino da Bologna.”) Domenico was probably Domenica Manzino da Padova which means Giacomo is likely a cousin of Mancino da Bologna. This Giacomo ends up commanding a company of mounted crossbowmen a few months later in Venetian service at the same time as Guido’s command shrinks drastically; likely the command was split.

[18] This skirmish is derived from a small cavalry engagement described in Sanuto on col. 157. As Guido’s forces were probably in the Prato del Valle at this time, then they would have been in an optimal position to support this attack.

[19] Sanuto col.162 and then col.165. Here he is identified alternately as a Bolognese capo named Gaspar “Stappi,” and “Stalpi.” These are non-existent names in Bologna and almost certainly a corruption of “Scappi.” Of these there are and were, plenty in Bologna, and there was a Gasparre Scappi who led some Bolognese troops into exile two years before (after destroying the Palazzo Marescotti).

[20] Cronologia della Famiglia Bologna con le loro insegne p.688

[21] This may well have been Achille Marozzo, the famous maestro, though we’ll never know for sure.

[22] This reached the point of ridiculousness where one old villager was captured and ransomed for a mere eight ducats.

[23] Sanuto, col. 171.

[24] Sanuto, col. 170.

[25] Sanuto says five Spanish banners. As best I can determine a Spanish banner was about a thousand men at full strength, though, it’s not clear how well they could have kept up those numbers.

[26] Sanuto, cols. 177-178.

[27] Santuo, col. 180.

[28] Priuli, p.352.

[29] Sanuto, col. 174

[30] De Mailles, pp. 165-167

[31] Opinions are varried on this. Some say the French had assembled a large force of men at arms to go meet some Florentine carts.

[32] Note there is some discrepancy as to the national identity of the cavalry that Malvezzi faced.

[33] Da Porto, p.125.

[34] Priuli

[35] Sanuto, col. 188.

[36] This is supposition based on the fact that Sebastian Moro and a Dandolo had divided the mounted crossbowmen between them and that Sebatian Moro was on this mission with Lucio Malvezzi. The numbers are unclear but Sanuto later says the operation used over 1,000 cavalry.

[37] Sanudo, col. 181.

[38] Sanudo, col. 191.

[39] Sanudo, col. 236.

[40] See www.muradipadvoa.it and Sanudo col. 190.

[41] See Priuli p.367. According to him the song became known after the last attack, but other sources mention it happening a few days before.

[42] Shellaberger.

[43] See de Mailles p.180.

[44] Muradipadova.it

[45] Priuli, p. 357.

L’union des princes: Louis XII, his allies and the Venetian Campaign 1509)

Note that Spinazzo and Sebastian will appear prominently later while Attila appears to have died at the Battle of Polesella a few months later. It is possible that Spinazzo was not in this section of walls and was serving as a reserve in the piazza as a broken lance, but it seems more probably, giving the nature of the siege that he was sent to fight alongside his fellow Bentivogleschi here.