The Quest for Manciolino: Printers Part 3

Nicolò 'lo Zoppino' d'Aristotile d'Rossi

Nicolò ‘lo Zoppino’ d’Aristotile d’Rossi was born in Ferrara sometime around the year 1478. His father, Aristotile d’Rossi was a notary in the city, and provided a quaint middle-class life for the d’Rossi household. While Nicolò wouldn't follow in his father’s footsteps, he would inevitably use the skills, literacy, and penmanship inherent in his father’s trade to forge his own illustrious career as a publisher, typographer, illustrator, and bookseller. The nickname, lo Zoppino, often attributed to Nicolò seems to have been a reference to the fact that he walked with a limp, however it’s unclear if this was a birth defect or a result of an accident in his childhood, regardless, the nickname would follow him throughout his life and into the back-alleys of Venice where it would take on a life of its own.

As a young man, wielding the raw tools of a potential tradesman yet defined in broader landscape of industry, Nicolò moved to Bologna in 1495 and looked to get his start in either printing or marketing. Bologna was the ideal landscape for an ambitious youth determined to forge a path, it was full of potential opportunities with its renowned university and cutting edge industrial infrastructure. The first record of Nicolò during this time is a receipt dated 14951, for a debt he owed to Bazaliero Bazalieri; this debt could’ve been acquired on account of Nicolò trying to have something published, but it’s more likely indicative that he started his apprenticeship with the Bazalieri press, and had asked for an advance on his wages. We can make this assumption because we see his name appear in print for the first time as typographer in a Bazalieri publication, Il libro del maestro et del discipulo, by Honorius of Autun in 1503, then in 1504 it appears again in two publications of a collection of, the Works of Serafino Aquilano, where he is listed as bookmaker and seller.

His presence in the production of the Works of Serafino Aquilano is significant, because the editor on that project was Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, who at the time had just finished his work, Viridario, which is a poem that contains a long passage about sword and buckler fencing2. Giovanni Filoteo Achillini’s brother, Alessandro was a famous professor at the University of Bologna, and courtier of the ruling Bentivoglio family3, who provide many links to the recognized fencing tradition of Guido Antonio di Luca, of whom we presume Antonio Manciolino was a student. This relationship could be significant on account of Achillini’s defense of the continued publication in the vernacular, a trait paramount to Nicolò’s career. Nicolò d’Aristotile would continue to work in the print shop of Constantine and Bazaliero Bazalieri until 1505 when either from a yearning to strike out on his own, the local famine that devastated the city that year, or a keen sense for the forthcoming cataclysmic upheaval slowly bearing down on Bologna under the new Pope, Julius II—or perhaps some combination of all the above—Nicolò moved to Venice, the publishing capital of the European world.

In Venice, Nicolò took on a new role, a bigger role, in concert with this skills as a typographer and bookseller he added the tune of editor and publisher, working with presses across northern Italy to carve a sizable stake out of the trade epicenters vibrant market. His new found role was coupled with the investment of a new found friend, Vincenzo di Polo. Vincenzo was a singer, a renowned soprano, who’d traveled all over Europe to apply his trade; from the courts of dukes, to royal banquet halls, out into the square’s of the popolo across the peninsula; Vincenzo’s voice was a treat for all, as such he’d acquired a tidy fortune for himself and upon acquiescing himself with Nicolò, formed a unique partnership. Between 1505 and 1513, Nicolò was attributed as editor in twenty-five works, which was a sizable output, however, over the next eleven years, between 1513-1524—the time of Vincenzo’s death—the pair would publish an astounding 139 books together. How these two men came to be partners we can only speculate, but what is clear is that they formulated a unique business strategy built upon a keen sense of what would satisfy the desires of a wider audience. Business-hoes by day, vigilante-satirist and show-men by night. Yes, Nicolò d’Aristotele d’Rossi would dawn his mask and cape, pick up his lute—becoming lo Zoppino—and take to the streets with his dear friend Vincenzo—from Milan to Pesaro, Bologna to Vincenza or Ferrara, back to St. Mark’s square—upon the wooden bench they would sing a verse from a book fresh off of their press; they were cantambanci, or cantastorie.

The cantambanco, or singing-bench, became a cultural phenomenon in Renaissance Italy. First utilized by traveling priests, blanket blessing passers-by in the Piazza, the post became more secular in the 16th century, and turned into a perch for gazettes, entertainers, healers, and booksellers. Taking a page out of the priors playbook, these cantastorie would print images on large sheets of paper, and point to highlighted scenes as they sang and played their way through a passage of a given text, or piece of news. Most of the performances were a verse or two of a selected work or news-piece, picked to end on a cliffhanger so the booksellers or gazetteers could guile their audience into purchasing a physical copy. While Vincenzo and and Nicolò weren’t the only bookseller-cantastorie duet to take to St. Mark’s Square or the Piazza Maggiore in Bologna, they were the most successful. This can be attributed to a few things; first, most of the publications they sought were in the vernacular, or Italian—rather than Latin, Nicolò also preferred to print in the octavo format, which attributed quick printing and the maximization of each page—minimizing time and cost, and finally they were just lucky. Their success, however, wouldn’t come without turmoil.

In November of 1509, Nicolò grabbed a stack of his freshly printed frotolla (a satirical poem), Barzoleta novamente composta de la mossa facta per Venetiani contra alo illustrissimo Signore Alphonso duca terzo de Ferrara, put them in his hand cart beside his bench and his lute, and headed for the ducal steps of Ferrara with Vincenzo. Passion among Italians has never been in short supply, and nothing invigorates an Italian’s passion quite like home; for Nicolò home was Ferrara, he’d entered his profession in Bologna and rooted his career in Venice, but Ferrara would always be home. Perhaps he was thinking back on the stories that his friends shared with him about the chaos and upheaval that followed the Popes overthrow of the Bentivoglio family in Bologna, or his clients stories about the corrupt papal administration in Perugia, maybe the rage of his fellow cantistorie in Verona, or printers in Milan; all projected upon his home in Ferrara, was enough to push a man who was already known to toe the line—over the edge. Nicolò neatly stacked his frotolla on the gate of his cart, set out his bench, and had Vincenzo pluck a cord as he stepped up on his perch, and sang his Barzoleta:

Your latest move

That you have made with your men

Towards Ferrara with great fury

Will bring you new woe

O wicked, Venetians

To have made this move

Against Alphonso’s power

Have you not thought about the consequences

O wicked, Venetians!

I do not wish to mock you here

Though it’s easy

Because you’re in the shoals

Without a pilot

If you want this frotelino

Put a hand in your pocket

take two quattrini from it

And put them in that hands of Zoppino

While his impassioned poem was successful in firing up his tense Ferrarese compatriots gathered about his bench, it also set off warning bells in Venice, and the Venetians weren’t really keen on descent at this time. Since the start of the Cambrai alliance against Venice, they’d become frighteningly efficient at clamping down on ex-patriots and patriots alike speaking out against the Serenisima, the party line became unity against all, and the penalties were harsh; for a lesser violation you would lose your tongue, and for more significant denunciations you’d lose your life.

What’s worse is, at this time, the Council of Ten—the CIA or MI6 of the Serenisima—was starting to hone the development of a spy network with a level of sophistication and breadth the world had never seen. The established baseline of Venetian espionage beyond the Terraferma was manifest in the gazette—a venetian word that means little news—where gazetteers across the peninsula, in Venetian employ, would send unsuspecting little pamphlets of local news back to a spymaster in Venice, the spymaster would compile a brief—not unlike the daily presidential brief—for the Council of Ten, who would review and act on a state level, send inquiries for agents to gather more information, or request covert action; like acquiring further confidential informants or conducting assassinations. It’s quite possible that Marino Sanuto was a spymaster for the Council of Ten, and in his compendium of gazettes, il diarii di Marino Sanuto, there are numerous coded messages—clearly meant for the eyes of the Ten alone—but beyond the obvious, there are unseen cyphers hidden in the rest of Sanuto’s diary, disguised as regular news, carrying hidden messages about the movement of armies, or scandals at court that could be used to blackmail someone down-the-road; all buried in a lost cadence of covert letters, only discernible with a key. The very people that comprised the spine of the Venetian deep-state would be the fellow cantastorie—the gazetteers, stepping on their benches beside Nicolò; therefore, it should come as no surprise that Nicolò and Vincenzo were promptly flagged, and arrested upon their return to Venice.

For an agonizing ten months Nicolò and Vincenzo sat in a Venetian prison cell awaiting their sentence, mulling over their words—would they really lose their tongues for telling the Serenisima they were up shits creek without a paddle? If there was a glimmer of hope it was that Venetian politics was polarized at the moment—this was in spite of the official government position of unity. About the time of Andre Gritti’s daring recapture of Padua, and in the aftermath of the coup when the full weight of the Cambrai League was brought to bear in response, arguments about the viability or necessity of maintaining the Terraferma—or the Italian mainland empire of the Venetian Republic—were rampant in the halls of government. Historical familial alliances were shattered as terse words were tossed back and forth, and tempers flared. Perhaps this was the same fervor that seeded the foolhardy inspiration for Nicolò and Vincenzo’s plunge with their frotollo.

This observation of Venetian political disunity is important to consider, because the man who inevitably stepped up to argue the cantitstorie’s case was an outspoken opponent of the reconquest of the Terraferma, Marino Morosini—a position that was well defined by Giorlamo Priuli in his Diario Veneto dal 1500 al luglio 1512. As the Avogadori di Comun, or free council representing our cantestori, Morosini was an influential figure in the opposition party, and put forth a rather legalistic case on their behalf4. He argued that the state couldn’t prove the identity of the cantestori, who were likely masked, nor could they assuage the credibility of an anonymous source without revealing the informant’s identity5. This case was enough to peel a few justice minded council away from the popular position of the Serenisima, while Morosini fervently carried his opposition proponents—who probably got a kick out of Nicolò’s poem and saw this as an important milestone in preventing a runaway effect of government overreach and censorship. The final decision landed 15 in favor of the defendants, and 12 in favor of the state. Morisini expertly navigated the political divide, and won Nicolò and Vincenzo a full restoration of their rights.

In spite of this episode, lo Zoppino would continue on—just as bold, just as boisterous, and always on the edge of taboo. In fact, he became so famous as a caricature, finding his way into satirical works of Aretino, Pietro Bembo and Teofilo Folengo that for hundreds of years after his death scholars would continue to debate whether the street singer and the book seller could be the same person; how could Italy’s most prolific Renaissance publisher be associated with charlatans and fools—criminals—peddling their wares in the streets? The high mindedness of this question—that would cloud scholars judgment for centuries—lends perfectly to the successful strategy that Nicolò and Vincenzo laid out, because it’s the same narrow logic that prevented their competitors from accessing the same market—the everyday Italian, and making the connections that would propel them into the stratosphere.

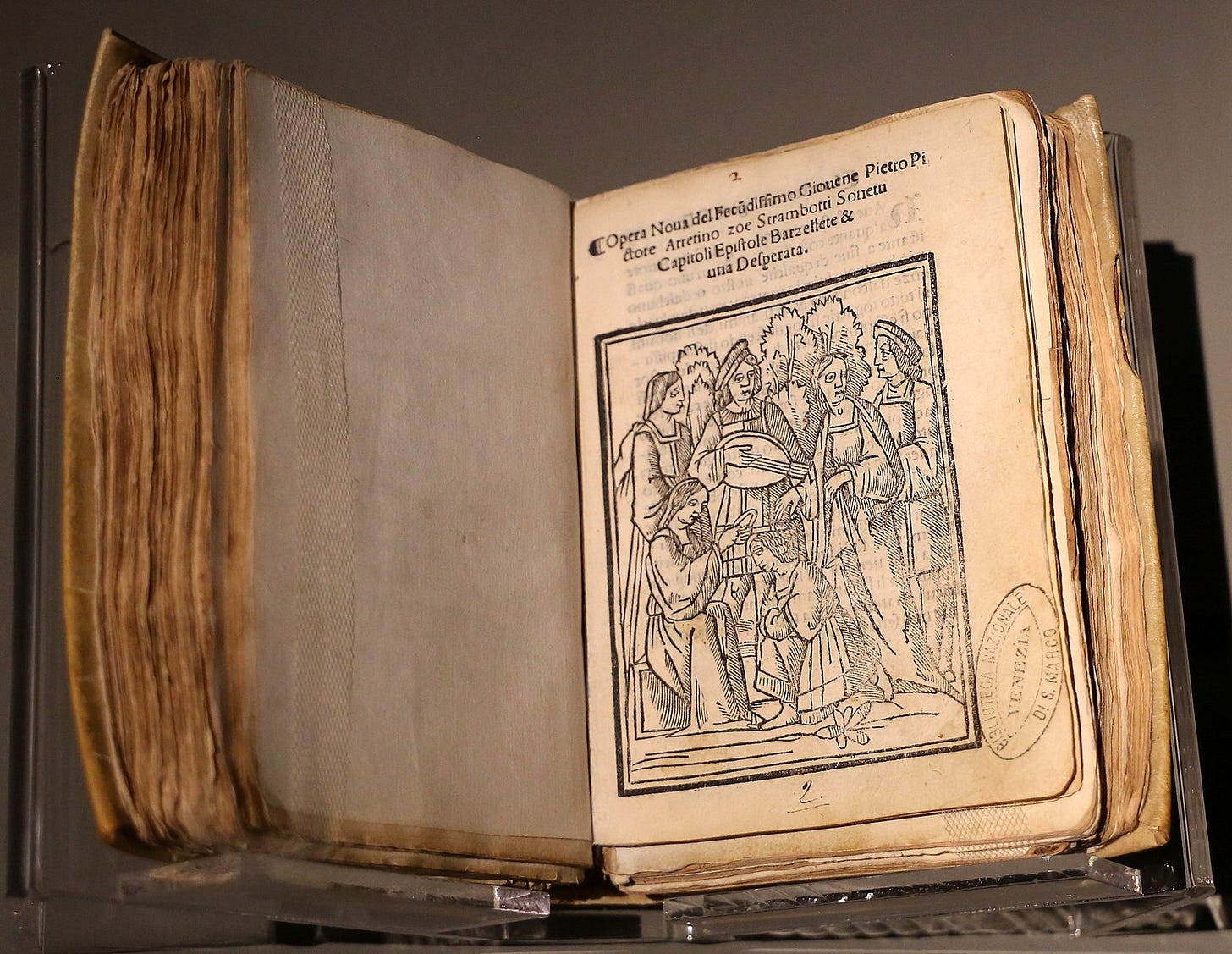

Among the community of cantastorie frequenting St. Marks square in 1511 was a young promising poet who’d just fled Arezzo, by the name of Pietro Aretino. Just nineteen—young Aretino had composed a scathing satire about indulgences, which enraged the local clergy, instead of laying low however, this cocksure poet wandered into St. Marks Square with a swagger looking to find a publisher—not a refuge. When he found Nicolò ‘lo Zoppino’ d’Aristotile d’Rossi, he found a kindred spirit. With his publication of Opeva Nova del fecundissimo giovene pietro pictore arretino, per zoppino, venezia 1512; Nicolò helped launch the career of one the great satirists of the 16th century, the Scourge of Princes.

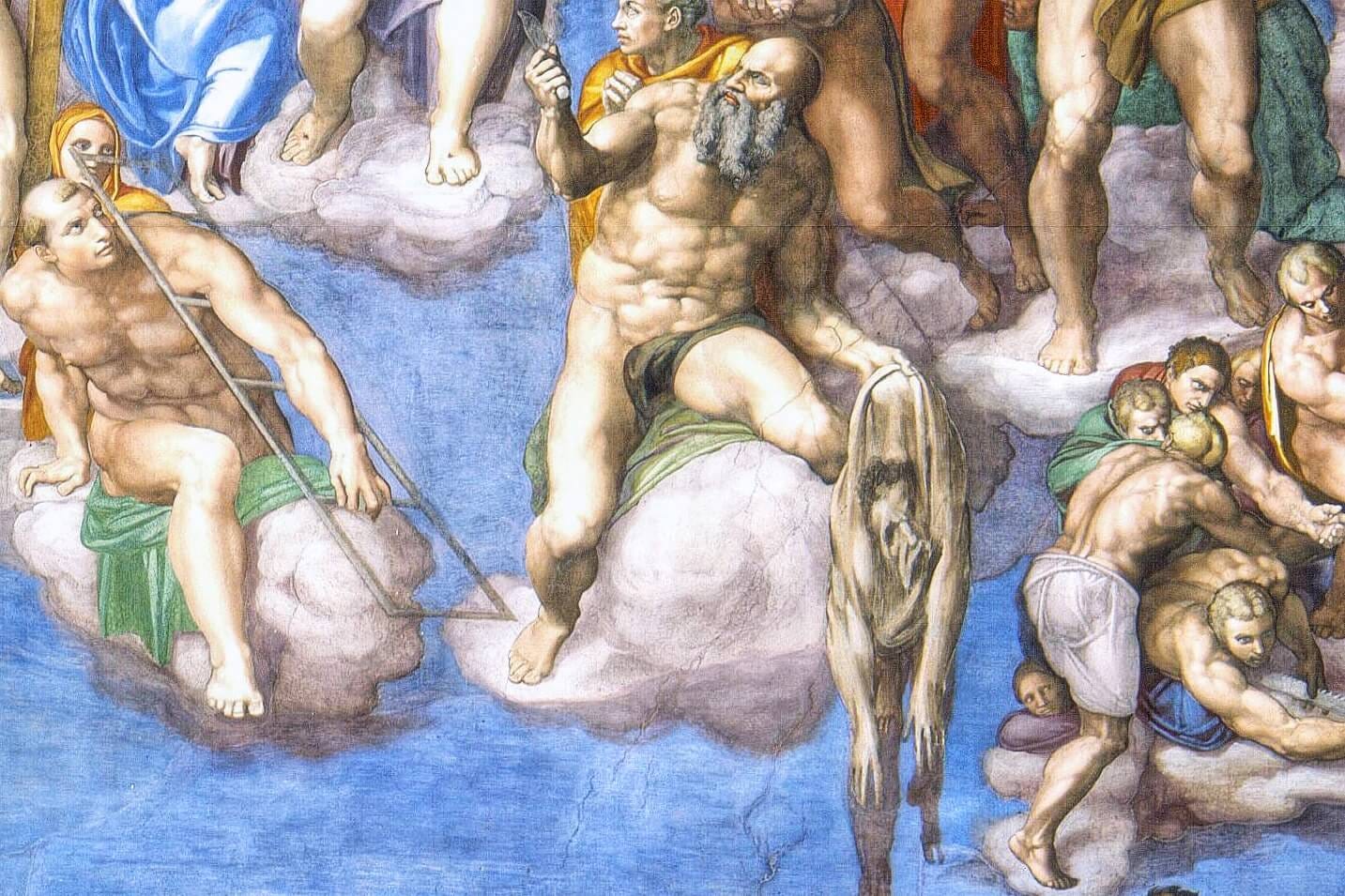

It would be a pleasant little satirical epitaph provided by Aretino later in their lives that would help modern readers and scholars of Nicolò d’Aristotile d’Rossi’s life better understand lo Zoppino. To preface this, Piertro had many friends, of whom Giovanni de Medici—better known as Giovanni della Bande Nere—was foremost, and it seems that the rugged bravado of Giovanni was an essential trait to tolerate Aretino’s witticisms, because to be a friend of Aretino took a certain level of thick skin—perhaps why Michelangelo chose Aretino as his model for St. Bartholomew in the Sistine chapel. A fine example of this is Aretino’s impression of his friend lo Zoppino, where Pietro muses that the Canestorie’s singing from the bench was like a prostitute who edges her clients to the point of climax, then demands payment to grant them absolution.

The alluring solicitations of lo Zoppino and Vincenzo ranged from the Classics to near contemporary Medieval works, into the passions of courtly literature on-down to the solemnity of devotions, and beyond into the adventures of Chivalric epics. These works were produced almost entirely in the Vernacular, or the local regional Italian dialect. Of Nicolò’s eventual four hundred and thirty-eight known publications only a handful were in Latin, and he never published in Greek. His audience went beyond the literate mendicant and aristocratic elite, Italy at the time was experiencing a surge in literacy, the citizens of the townships, duchies and republics across the peninsula were as independently-wealthy as most kingdoms across the European continent. Within the wealth structure of each analogous family—whose numbers per city could be in the hundreds—was a corresponding demi-court of scribes, notaries, merchants, and courtiers who also needed to be literate to function within the framework of the emergent Renaissance society. It was this majority that Nicolò appealed to, and he wasn’t alone, as he echoed the sentiment professed by his friends; Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, and Pietro Aretino.

The other unique characteristic prevalent throughout Nicolò’s publications was the use of the Octavo format. The style of the time was to print in Folio, where each sheet of paper is folded into another, and has four pages of text printed on it, where Octavo format was folded three times, and each sheet would have sixteen pages of text printed on it. Only seven of his four hundred and thirty-eight publications would be in a format other than Ocatavo, of which three were in the aristocratic duodecimo—where the page is cut and folded into 12 leaves—and four were in Folio6. The benefit of Octavo was again, that it provided for quick printing, and ample space for smaller publications, like his daring frotolla, or other poems and songs composed by his fellow cantestorie.

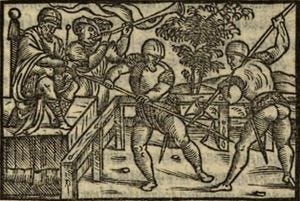

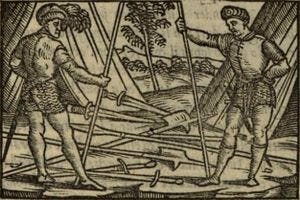

It wasn’t all avangarde street art for Nicolò however, he dwelled in the more sophisticated realms of literature as well. One of the hallmarks of Nicolò’s works were his beautiful woodcuts. Both his illustrations, and his marginalia won him tremendous fame, and were as essential to the growth of his business as his after hours duets. At the turn of the decade, 1518-1524, Nicolò started investing heavily in the realm of Chivalric Literature where his dynamic woodcuts really caught the attention of his clientele and readership. His first significant foray into the fantasy epics was the work Orlando Innamorato, by Matteo Maria Boiardo, producing the work in popular print as a complete set—all three volumes in one book—for the first time since it’s completion in 1495. This along with his street singing and popularity at the Ferarese court brought him together with Lodovico Ariosto, whose Orlando Furioso, was a continuation of Boiardo’s epic. For Ariosto, Nicolò would produce the first fully illustrated version of Orlando Furioso, and set off a craze that would make Lodovico’s work the most widely read, republished, re-illustrated, pirated and popular work of the 16th century.

This lapse in narrative reinforcement of Nicolò’s proclivity toward civil disobedience might give the false impression that after his run-in with the Serenisima he softened his edges. To the contrary, Nicolò never lost his desire to traverse the periphery of the established norm. In 1525 Nicolò published—for the first time—in Italian the collection, with the declaratior of the ten commandments: of the Creed: of the Pater noster, by Martin Luther, whose works in 1521 had been reprimanded by a papal bull issued by Leo X, then subsequently banned, before this episode was capped with an excommunication for the Wittenberg Monk. Naturally, this publication in the vernacular was met with significant push-back. That didn’t deter Nicolò however, because he published the same book a year later under the pseudonym Erasmus. Speaking of—Erasmus of Rotterdam, the provocative priest who was in no way a fan of Luther, but was also a reformationist in his own right, and who’d found close friends in the court of Charles V and Henry VIII; he too would have a few of his works printed by Nicolò, and they would be some of Nicolò’s only publications in Latin. For most printers in the Italian sphere, poking the church was a dangerous financial undertaking, but Nicolò didn’t give a flying Francis, beyond Luther and Erasmus, he would go on to print the works of Bernandino Ochino—the Capuchin reformationist—first in 1530, and again in 1542, when Ochino was forced to flee Italy.

This edgy counter-culturalist was the man that inevitably printed the extant copies of Antonio Manciolino’s Opera Nova, To Learn How to Fight and Defend with any Sort of Arms, in 1531. The small sixty-three page octavo book, in the vernacular, with nine elegant woodcuts.

Hey! Before you go, take a moment to subscribe to the Substack. We’ve got the conclusion of Part 1: Printers, coming out soon, bringing this all together, before we transition into Part 2: Patron, and we start learning about Luis Fernández de Córdoba y Zúñiga. Also, it’s summer time, and we can’t be landlocked land-lubbers when it’s peak beach season, so keep your telescopes peeled for Pirates of the Mediterranean.

Sources:

ROSSI, Niccolò d'Aristotele de', known as Zoppino by Lorenzo Baldacchini - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 88 (2017) https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/rossi-niccolo-d-aristotele-de-detto-lo-zoppino_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

FASANINI, Philip by Floriana Calitti - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 45 (1995) https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/filippo-fasanini_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

https://www.unibo.it/en/university/who-we-are/our-history/famous-people-and-students/alessandro-achillini-1

Libby, Lester J. “The Reconquest of Padua in 1509 According to the Diary of Girolamo Priuli.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 3, 1975, pp. 323–31. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2859809. Accessed 12 June 2023.

Massimo Rospocher (2014) ‘IN VITUPERIUM STATUS VENETI’: THE CASE OF NICCOLÒ ZOPPINO, The Italianist, 34:3, 349-361, DOI: 10.1179/0261434014Z.00000000096

Harris, Neil. Review of Alle origini dell'editoria volgare. Niccolò Zoppino da Ferrara a Venezia. Annali (1503-1544), by Lorenzo Baldacchini. The Library: The Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, vol. 14 no. 2, 2013, p. 213-217. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/510856.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantastoria

Degl’Innocenti, L. and Rospocher, M. (2019), Urban voices: The hybrid figure of the street singer in Renaissance Italy. Ren. Stud., 33: 17-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/rest.12529

Zoppino, Niccolò, CERL Thesaurus accessing the record of Europe's book heritage: https://data.cerl.org/thesaurus/cni00022156

ARIOSTO, Ludovico by Natalino Sapegno - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 4 (1962) https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ludovico-ariosto_(Dizionario-Biografico)

Edward Hutton, Pietro Aretino: The Scourge of Princes (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922)

https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Opera_Nova_(Antonio_Manciolino)

ROSSI, Niccolò d'Aristotele de', known as Zoppino by Lorenzo Baldacchini - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 88 (2017) https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/rossi-niccolo-d-aristotele-de-detto-lo-zoppino_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

FASANINI, Philip by Floriana Calitti - Biographical Dictionary of Italians - Volume 45 (1995) https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/filippo-fasanini_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/

https://www.unibo.it/en/university/who-we-are/our-history/famous-people-and-students/alessandro-achillini-1

Libby, Lester J. “The Reconquest of Padua in 1509 According to the Diary of Girolamo Priuli.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 28, no. 3, 1975, pp. 323–31. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2859809. Accessed 12 June 2023.

Massimo Rospocher (2014) ‘IN VITUPERIUM STATUS VENETI’: THE CASE OF NICCOLÒ ZOPPINO, The Italianist, 34:3, 349-361, DOI: 10.1179/0261434014Z.00000000096

Harris, Neil. Review of Alle origini dell'editoria volgare. Niccolò Zoppino da Ferrara a Venezia. Annali (1503-1544), by Lorenzo Baldacchini. The Library: The Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, vol. 14 no. 2, 2013, p. 213-217. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/510856.