The Quest For Manciolino: Printers Part 2

Early Printing in Italy and Stefano Guillery

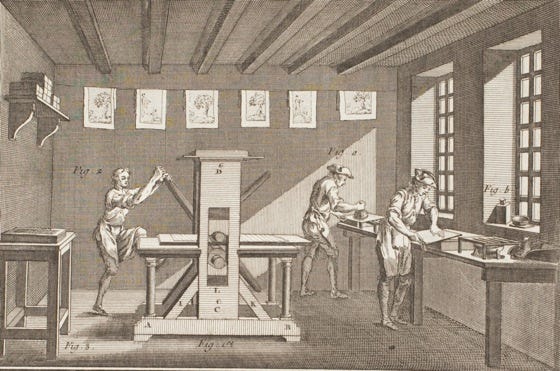

Conrad Sweynheim and Arnold Pannartz were two of the displaced artisans that were forced to leave the city of Mainz in the aftermath of the Diocesan Feud. Both men were clerics who’d learned to ply the trade of printing in the shops of either Guttenberg or Shöffer, and having been forced out of their home’s, decided to start anew in Italy. They settled down at the monastery of St. Scholastica in the village of Subiaco just north of Rome. By 1465 they’d constructed their own printing press in the city, the first in Italy, and their first publication was the work of the schismatic bishop Donatus—perhaps fitting given what they’d been through—next was Cicero, then Lactantius, and finally St. Augustine. Initially they ran into a bit of a problem, Italians were very particular about type faces, but they were patient, and listened to the feedback from their customers and made some necessary amendments to suit Italian stylistic preferences; namely using italic characters instead of the bold Kurrent style font preferred in Germany. Having perfected their techniques, they took their show to Rome, where they found a space to setup shop in the home of the brothers Piero and Francesco d’Massimi. The two cleric’s printing partnership would continue for another half decade before financial insolvency in an ever evolving market would claim their business. While Sweynheim and Pannartz’s press couldn’t thrive in the Roman market, one printer who did find a modicum of success was Stefano Guillery.

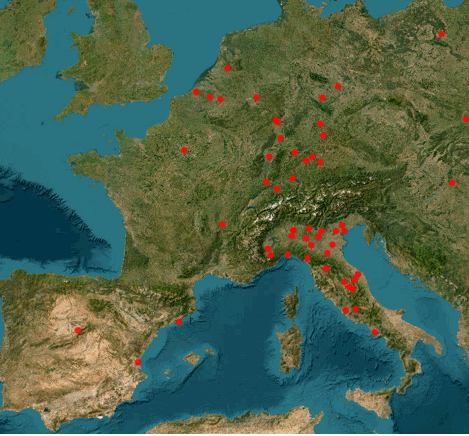

Guillery was a native of Lunéville in the duchy of Lorraine. Interestingly, Lothringia was a veritable hotbed of soon-to-be standout printers and foremen, and perhaps representative of an underappreciated epicenter for the regrowth of the technology; eg. the first book printed in Zurich Switzerland was printed by a Dominican Monk from the duchy of Lorraine by the name of Albrecht von Weissenstein, while the innovative pioneer of printing in England, William Caxton, upon his death passed on his business to his foreman and business partner, the Lothringian, Wynkyn de Word—also a native of Lorraine. Further, we can add the success of Stefano Guillery. A simple hypothesis is that more than a handful of the refugees fleeing Mainz decided to settle in the duchy of Lorraine. The region had all of the elements that a turned-out yet ambitious print-shop worker might desire when looking to become an entrepreneur; it was close to their old homes in Mainz, it had overlapping regions of influence and a shared language, but most importantly it had wine. Many of the presses that propelled these once obscure figures into the chronicles of history were converted wine presses, and perhaps unsurprisingly, when you see the instances of their early achievements illustrated on a map of Europe1, it’s easy to see the technology re-emerging where wine was prevalent.

Stefano Guillery moved to Rome sometime around 1494, and may have taken up work as a draftsman and engraver for the Basel born Johann Besicken, who cut his teeth under the Swiss Printer Martin Flach. Guillery had brought a style of engraving with him from his home in Lorraine that was unique, the so called ‘French style’ of decoration, and by some accounts made a considerable early impression on the local industry. By 1506 Guillery was listed as a bookseller at the University of Rome and in the same year his name started to appear in the books printed by Besicken with the associated title, publisher. Then in 1508, Guillery purchased the operation of his now partner Johann Besicken, and moved the equipment to a house in Parione, where he setup his own workshop.

Printing in Rome had reached new heights by this point. Pope Julius II had harnessed the power of the printing press, and used it at a rate which was almost twice that of his most prolific predecessors—Sixtus IV and Innocent VIII, publishing almost ninety-four bulls, briefs, decrees and monitoria within the city of Rome during their reigns over the Holy See. Now, it wasn’t that extra-papal ecclesiastical communique hadn’t graced the tooled copper letters of the press before Julius II’s vestige—or even in greater numbers—it was that the Pope himself had begun to expressly ask for his documents to be distributed with the haste and efficiency that the printing press afforded, rather than cardinals or bishops outside of the Vatican cutting out the middleman—the copyist—to disseminate necessary materials faster; or ambitious printers asking for permission to print ecclesiastical documents for a quick profit. Now, the printers had the attention of God, and that was true power.

Amidst the fervor of the growing industry, Guillery’s fledgling operation printed fifteen books between 1508 and 1510. However, his big break came in 1510, when he was brought into collaboration with Ercole Nani; a Bolognese publisher known for printing books in Italian, and Ludavico Degli Arrighi; who was a renowned illustrator and calligrapher from Verona, to produce the Itinerary of Ludavico de Varthema. de Varthema was the famed Bolognese explorer who traveled from Mecca, through Southeast Asia, India, all the way to the Maylay Archipelago before circumnavigating Africa to get back to Portugal, and might have been personally responsible for bringing Nani, Guillery and Ludavico degli Arrighi together for the project. The work was met with a lot of anticipation and during the course of its production, the group produced special copies that degli Arrighi illuminated for illustrious patrons like Vespesiano Colonna. They finished the project in 1511, and from that point forward the duo of Nani and Guillery were the hottest press in town!

Book by book, Guillery’s publications brought him further into the inner circles of the Vatican—Erasmus, Egidio Gallo (Poet of Agostino Chigi; Pope Julius’s right hand man, and the richest man in Rome), Matteo Bonfini de Ascoli, Giulio de Simone, and on. He had gathered so much momentum that the moment his star should’ve collapsed in on itself—the death of his collaborator, Nani—it shined even brighter instead. In 1515, now on his own, Guillery was approached by the Flemmish priest Jan Heitmers, and the publisher Filippo Beroalso the Younger on behalf of the Pope Leo X, with the exclusive honor of printing the unpublished first five books of Tacitus’ Annals, which had just been discovered in the library of the monastery of Corvey, in Westphalia. The agreement came with a ten-year copyright, guaranteed by the Pope and the Publisher, dated 14 November, 1514.

Stefano followed this up by printing the works of great Mathematician Juan de Ortega, followed by Historia Parthenopea for Alonso Hernandez, then his output shifted considerably, as he became one of the official printers of the papal court, and his production queue was saturated with bulls, edicts, rules, ect. It wasn’t all Papal bull that was leaving Guillery’s press at this time however, a few notable publications hit the market, including a reprint of Varethma, commissioned by Cardinal Rafael Riario; (the first time in the record that Guillery is shown to have been given the title of Official Printer of the Curia).

—This was the man whose doorstep Antonio Francesco Manciolino darkened in the fall of 1518.

On 14 November, 1518, the swordsman picked up his pen and inked a contract for the publication of one thousand copies of a, Trattato Sull’Arte Gladiatoria. The agreement was that he would sell each copy for a price of one ducat, with a promise to compensate Guillery for each copy sold. It is a weird contract. First, one thousand copies was a lot—for perspective, the average publication at about this time was between four to five-hundred copies, with rarer selections eclipsing the one thousand copy threshold, and these were usually only pamphlets2. Second, it’s hard to tell if this was a print on demand endeavor (which seems highly unlikely), or an attempt at a Renaissance crowd-funding effort; either way, we’re not exactly sure if anything ever came of this contract, because no known publications have survived in the public purview. What’s striking about this affair, from a HEMA perspective, is how accomplished Guillery was at the time of this contract, by this point he’d become one of the printers in Rome, there were hundreds of other options—probably cheaper options—Manciolino could’ve pursued, but deep connections or a strong sense of bravado led him to Guillery’s doorstep.

Given the future proximity of Manciolino’s patron, Don Luis Fernandez de Cordoba, to the Curia it would be easy to assume that Manciolino was simply privileged to the Official Printer of said Curia—or perhaps he actually was—but, as we’ll see later, Don Luis wouldn’t make his way to Italy until after 1521, so it wouldn’t have been through his influence that Manciolino would’ve found his way to Guillery. There are two threads to lay bare across the warp however. The first is the closeness of Guillery’s associate Ludavico degli Arrighi, to the Colonna family; he produced special editions of Varethma for Vespesiano Colonna and copy of Aristotelian Ethics in Latin for Vittoria Colonna. The next thread is Rafael Riario, the brother-in-law of Caterina Sforza. Cardinal Riario had a habit of hiring Bolognese cut-throats, and had a long standing claim over Bologna’s neighbor Imola.

Guillery would go on to print some illustrious titles, including Henry VIII’s condemnation of Martin Luther, Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Martinum Lutherum, mostly producing his texts in Folio format, with his beautiful—intricate French etchings. From migrant to printing magnate; Guillery was truly a force in early Roman printing.

Hey, we hope you enjoyed this installment of the Quest for Manciolino! To make sure you don’t miss more great content, just like this, hit subscribe! It’s free…unless you want to bless us with your Gold Bolognini!

Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana fondata da Giovanni Treccani S.p.A. © Tutti i diritti riservati Partita Iva 00892411000

Clair, Colin. A History of European Printing. United Kingdom, Academic Press, 1976.

Sachet, Paolo. “The Rise of the Stampatore Camerale: Printers and Power in Early Sixteenth-Century Rome.” Print and Power in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800), edited by Nina Lamal et al., Brill, 2021, pp. 181–201. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctv1v7zbf2.13. Accessed 14 Dec. 2022.

Image Courtesy of: https://www.througheternity.com/en/blog/art/michelangelo-last-judgment-sistine-chapel-vatican.html#

Jeremy Norman’s, History of Information, By 1500 Printing Presses are Established in 282 Citie: Link

Atlas of Early Printing (uiowa.edu)

Historyofinformation.com: “The average print run of a 15th century printed book has been estimated by some methods of calculation as between 400-500 copies”