Introduction:

We’ve just been down a long and winding logical deconstruction of Viggiani’s lo Schermo, and I think that this is probably a good time to take a step back and apply similar logic to the other authors in the Bolognese corpus. Everything we do in HEMA is interpretation—results of which vary considerably. So how do you come up with a good interpretation and how can you build a framework to judge other interpretations? Furthermore, how can we judge a source?

In Viggiani’s text he acknowledges his forebearers, and addresses the conundrum of infinitesimal potentiality and actualization, and reduces everything down to a perfect schermo. When I was writing that article, I discussed the subject matter in detail with my students, and one of them quipped, “it would be funny if you came out of your competitive HEMA retirement and did nothing but Viggiani’s perfect schermo.”

It's a silly thing to think about, but it's also an intriguing line of thought. How many people do you see doing nothing but Viggiani’s perfect schermo? It has every possible consideration you can imagine, so what's stopping someone from entering a tournament with the sole purpose of mastering Viggiani?

I think the argument you'd hear is: it's too limiting, or it's too basic—its not fun enough or its boring. I guess it's up to the reader.

That said, what is it that we look for in a source? The opposite argument is often leveled against a text like the Anonimo Bolognese: ie. it's too dense, there are too many plays, etc. So, how can a student of Bolognese fencing get to a place where they can truly appreciate either the complexity or the subtly of a source like the Anonimo or Viggiani respectively, and every author in-between? That's the goal of this article, and I believe the answer is buried in Viggiani’s logical digression.

Objective:

To start—I can't give you a perfect answer, but I can share my experience and you can do with it what you see fit. We all judge a source of information’s worth based on how close it brings us to achieving our own personal goals; be it a historical text, or some guy writing a blog post on Substack. Similarly, people view HEMA in number of different ways, some see HEMA as a venue for competitive excellence, some see it as a process of re-creation, some may just think swords are cool and as long as it gives them the requisite skill in that pursuit they're glad to take part—ie. how close does this bring them to fulfilling their dream of being either Aragon or Geralt of Rivia. The salty greybeards of HEMA will gladly tell you that parts of x, y or z are antithetical or heretical, and that's fine too; I have my own biases.

The purpose of this article is not to tell you that you're doing HEMA wrong, or to demonstrate some superior line of reasoning. Instead, I want to share with you how I approach HEMA—especially when it comes to interpretation—with the objective of affording you perspective, so you can filter it through the lens of what’s important to you, and utilize it as best suits your pursuit.

A bit about me. Longtime readers or listeners to the Art of Arms podcast know that I am a nerd. I value the historical context and the realization of the source material—the actualization—way more than I do competitive success. Despite this, I have been very successful in competition. It's important to point this out, because I'm going to argue for something that—to some—will ring as heterodox; two truths, but rests in the often misunderstood objective of Viggiani’s lo Schermo and Marozzo’s Opera Nova. Many of you will already share this perspective, but for others this may be the first time you’ve read something like this. So, regardless of your experience I ask that you just bear with me. My hope, is that I will present this argument to you in a way that will provide sustenance regardless of your existing mindset or experience.

Principle vs Technique:

In my little-less than a decade of experience teaching, practicing, and competing in HEMA I've found that there are two common approaches to the art: principle and technique. Simply defined we can reduce a principled approach down to seeking the why, and a technical approach down to seeking the how. A common scapegoat for those who pursue either in isolation is: for the technique oriented; because x or y master says so, and for the principled fencer; because it works.

Both of these conclusions lead to some variation of less than ideal fencing, or a self imposed plateau that limits a fencers ability to actualize their full potential. It's not that either argument is wrong, they are simply incomplete. Allow me to elaborate.

For the technical fencer there likely has been or will be a moment when you share a play or passage of text with someone, and that person will say, “yes but I wouldn't do that” or “yea, but I would do this”, challenging your interpretation and perhaps shaking your confidence in your understanding of what you're trying to convey. Similarly, for the purposeful fencer, you may draw the ire and scorn of a technical fencer who sees your fencing as a-historical, eg. “they’re just a sport fencer,” or “that isn't textual” or “that’s just sabre bro.”

While both of those arguments can be true, they lack nuance and perspective. They're too biased toward either extreme to seek truth or purpose. They're excuses. This leads either extreme to retreat into their proclivities, and further exaggerates the issue at hand. This often results in categorization and self-denial, ie. “he’s just a hand sniper” or “he's a pointy-boi” or “they never bind” or on the other side; “that person’s HEMA ratings suck” or “yea, but (s)he can’t do it in sparring,” [Insert your favorite gross generalization here].

This is not to deride the community writ large, any group that sees value in something will seek to preserve it. Thus, a fencer’s goal, their pursuit of excellence—be it competition or re-creation—will supercede their willingness to compromise. We all have our tribes.

I've focused a lot on the negatives, but allow me to clarify that both approaches offer tremendous benefits. The principled fencer’s utilitarian approach to fencing—more often than not—yields a higher rate of success in competitive environments as opposed to their purely technical counterparts. That's why there seems to be a never ending pipeline of Olympic or sport fencing practitioners tearing up local tournaments across the world. A well honed sense of measure, footwork, and tempo can take you very far. Simply put, there are rules that govern fencing regardless of system, style or weapon.

On the other end of the spectrum, the technical fencer is pursuing a more pure expression of the art. They're more adept at matching the body mechanics and seek to bring to light a more literal interpretation of the source material. Often times this is framed as a more martial approach, the extreme of which is referred to as ‘real deadly fencing’.

So, how can we bring this all together? To mend this void, let me suggest an intermediary solution that could enliven the dusty old texts at the heart of HEMA for both pursuits; ie. those who wish to pursue excellence in competition and those who wish to preserve the the art of historical fencing. A path for the technical fencer to become more purposeful, and a purposeful fencer to find joy in the technical elements of the texts.

What is a Technique?

Regardless of discipline, master, timeframe or weapon, the typical presentation of a play or technique follows a fairly standard pattern: If a then b, if c then d. If you're fortunate a and c are clearly defined (*cough*—Marozzo—*cough*). Alas, that isn't always the case. What we come up with most of the time is a patient or b-side action (perpetrator of a and c) that renders the proper stimulus to execute the agents technique (b and d). The challenge of the instructor or communicator of said technique is to then train the proper stimulus and response into their students or peers. Then we drill the technique ad infinitum, and take it into sparring or fencing, so we can troubleshoot the failures, reinterpret, reintegrate, rechallenge, and scale it up again.

This is the technical progression. The challenge of a purely technical pursuit is that it requires the proper stimuli to facilitate the technique, and a common problem that arises between interpretation and actualization is the quality of the stimuli. That is, if the actual quality of a or c varies from the trained quality of a or c, then the execution of the technique fails.

This is not a problem unique to modern HEMA. In fact, many authors discuss the challenge inherent in the transition from training or controlled stimuli to the reality of fencing.

The second are the natural cuts of those men who know nothing of this profession and throw certain bizarre blows that cannot be defended against but by those who have much practice in this virtue. Wishing to learn to defend against these natural cuts, it is necessary after you have learned to throw thrusts and cuts well that you recognize tempo and measure and that you know how to fence with those who do not know of them. Begin to practise with those who know nothing and let them throw at you in their own way. Parrying with the sword and dagger according to what you see he throws at you, throw at him on the side he uncovers. Fencing with various men, you will learn how to parry natural cuts. It is for this reason that it is no wonder that some good fencers, contending with those with no knowledge, are quite often struck—that is, because they are unpractised with those who know nothing, they therefore do not know how to parry natural cuts.

—Nicoletto Giganti, Libro Secondo (1608); Vansteenkiste, Wiktenauer

Nicoletto Giganti was well acquainted with the full frontal reality of his cock swing peers in the salle, but realized that the minuta of their perfect parries were perfidious against the reality of picking a fight with pompous drunken sailors stumbling back to the arsenal in Venezia. One must become acquainted with the ‘bizarre blows’ of the uninitiated.

A similar anecdote, although directed toward the necessity of training with sharp swords, is present in Angelo Viggiani’s 1551, lo Schermo:

ROD: I would not say now that you cannot do all those ways of striking, of warding, and of guards, with those weapons, and equally with these, but you will do them imperfectly with those, and most perfectly with these edged ones, because if (for example) you ward a thrust put to you by the enemy, beating aside his sword with a mandritto, so that that thrust did not face your breast, while playing with {blunted sword}, it will suffice you to beat it only a little, indeed, for you to learn the schermo; but if they were {sharp swords}, you would drive that mandritto with all of your strength in order to push well aside the enemy’s thrust. Behold that this would be a perfect blow, done with wisdom, and with promptness, unleashed with more length, and thrown with more force, that it would have been with those other arms.

Viggiani, lo Schermo; Swanger, pg. 14

Note, that I'm not advocating for the use of sharp swords here, but what I believe this passage highlights is a phenomenon common to competitive fencing. That is, having something to lose— like life and limb—versus training in a controlled safe environment, mirrors the difference between familiar fencing with your peers and the adrenaline-filled reality of competition. You can make tight, well timed parries against the consistent structure of a well practiced friend, but when that endocrine response kicks in you're more likely to push your responses to an unfamiliar end.

Both of these historical anecdotes represent factors that complicate a technical approach. What I often find lacking in interpretations that err too far in a technical direction is a sense of humanity—which is a weird thing to say, so allow me to explain. People come in all shapes and sizes with a number of factors that limit their ability to execute a technique, or experiences that engender their own unique interpretations.

If you step into the ring with someone, and say to yourself, I'm going to do Marozzo’s second part of the abatimento di spada sola—this’ll get ‘em! 90% of the time it isn’t going to work beyond the falso impuntato. Or, take the first part of the abatimento, which has an eight action progression—probably not going to happen.

So how do you take the words of an author from a half millennia ago and create something that works regardless of this inevitable variation?

What’s the Purpose:

Every play has a purpose, but before any further digression in that direction, let’s take a moment and discuss the difference between an abatimento, a combattendo, and an assalto—because context matters. Let’s start with an assalto, plays that are considered an assalto are usually performed with a blunt sword (spada da lato), and they are usually performative. An abatimento has more ritualized aura, the word abatimenti historically was used in the chronicles to describe a passage of arms, or fighting in a duel. It's structured, it has rules. Where a combattendo is visceral, it's a random fight—a bar brawl.1

Then on Carnival Monday he fought the Carnival and Lent battle with some bands of young men armed with rotella on their arms and two lances each without an iron, and with the swords at their side without edge or point; and divided into two parts, they began to throw with haste, and then to play [gioucare] swordplay. Once this game was over, two other teams arrived.

—Ghirardacci pg. 342

So, when authors like Marozzo and Manciolino subcategorize their text with these pretexts what are they trying to tell us?

There are a number of clues. The first, most obvious one, is whether or not they're performed with a sharp or a blunt sword. What does that tell us? Viggiani and Giganti already answered that for us, didn't they? There's a real sense of danger.

This is not to deride or unsubstantiate the efficacy of their assalto with some hierarchy of ‘realness’, to the contrary, their assalto—often performed with the spada da lato—in many ways are in fact their most technical and artful passages. They are how the master envisioned the progression of a fight.

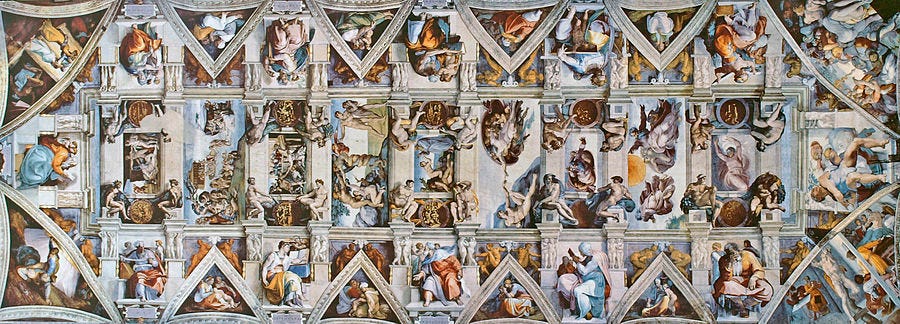

Knowledge of this will help you understand the context, but it won't help you bring the art to life. Understanding that Michaelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel at the behest of Pope Julius II to mark the power and prestige of the militant church or that most of Leonardo da Vinci’s female portraits are of Ludovico Sforza’s mistresses won't make you a legendary painter. However it will give you context into the artists frame of mind. It gives you a clue as to why.

The next layer of purpose is also—usually— stated. Is it an attack or a defense? Easy enough, right? Sure. We can relate this to the subject of a painting. The Sistine Chapel is full of Biblical allegory, and while this requires some contextual understanding, it's relatively easy to identify and infer.

Similarly, there is an implied dichotomous relationship in fencing; agent and patient or attacker and defender. It's fairly easy to see on the surface level and gives you an understanding of the subject of the play or passage. This subject will inform the purpose within the context of the text.

Now we begin to see the technique. If a then b, if c then d, etc.

We can relate this to something like the application of paint to the ceiling to give it color. Michaelangelo used a variety of grey or blue backgrounds with pops of color coming from the clothes of his figures who he envisioned as white southern Europeans in skin tone and complexion. We could argue the use of color gives the work a sense of liveness—we, as humans, see a spectrum of colors and gradients and a mono-tonal reality just wouldn't do. This is to say nothing of the realism or factual reality, it's simply a means or a process.

Now, if I told you to take the elements that we’ve outlined in our analogy of the Sistine Chapel, and I asked you to paint a similar masterpiece using only context, purpose, and means—that is I handed you a brush and paint, then asked you to paint my ceiling, how do you think you would fare?

It probably depends on your current technical understanding of the art of painting.

Form:

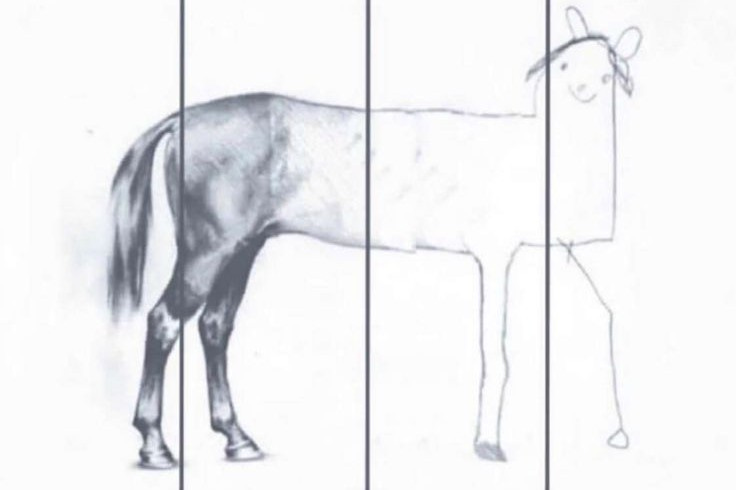

When artists like Leonardo da Vinci or Michaelangelo entered into an apprenticeship with a master in the so called ‘Florentine school’, their first assignment was to learn form. This instruction was typically executed through sketches; the sketch of an object being the most fundamental conception of any work of art regardless of medium.

Those cuts or thrusts you execute over-and-over again, or the variety of steps you learn when you're a beginner are tantamount to the beginning stages of learning to execute form—a sketch. Interestingly if you talk to some of the best competitive fencers in the world, as I have, you'll find that they never stop drilling the fundamentals—they never stop sketching. That is, they never stop pursuing the perfection of form.

When one form is laid over another you begin to have the rendering of a subject, with each form representing the means or the process of creation. The resulting sketch is only as good as the artists ability to execute the form of the object they're trying to represent.

The execution of form is technique. In the process of learning to create a form, an artist was taught a variety of techniques. Elements like shape, shading, light, perspective, and proportion. As they acquired new skills and techniques, they would apply them to their sketches—over-and-over again.

For the martial artist, the implementation of form—whether it is in solo practice or in partnered drills—can be categorized in two ways; quality of movement and execution. That is, I can execute a technique, and my quality of movement can be lacking, similarly I can have a high quality of movement and fail to execute a technique.

Finding the harmony of these two elements is an area where technical fencers tend to excel. That process of drill, pressure test, and reinterpret highlighted above. It's also an area where principled fencer's tend to fail, in that—in my experience—their quality of movement is lacking, as they tend to focus on the execution, and as long as that is sufficient they’re fine with sacrificing the later.

We could relate this to the trope of the bouncing sport fencer fixed in a point forward guard. It's an image that would look awkward or unnatural when juxtaposed onto the battlefield of Pavia in 1525, or into the steccato at Castello Mantua in 1516 when Guido Rangoni and Ugo Pepoli squared off in their famous duel.

The question is, does form have a purpose? Beyond the rendering of a believable image that interposes the function of realism into a otherwise two dimensional representation of a subject, art—especially in the modern world—is also about conveying emotion. Enter the abstract. Before we digress into the abstract any further, allow me to answer that question in the affirmative.

Does form have purpose? Yes. The HEMA and WMA communities have, for some years now, tried to create safe and effective tools that simulate the realistic analogues of historical weapons. One could reasonably argue that this is one of the key factors that separates historical fencing from it's sportive or Olympic counterpart. Foil vs Feder.

Yet that doesn't stop the purposeful extreme of the sportive fencer from succeeding. So how is that significant or relevant? If your goal is historical realism the absurdity of the stereotypical sport fencer amongst the a pike-laden wall of Lanksnechts or Reislaufer at the battle of Pavia is enough. But there's more to the story, a silent killer of dreams, when reality meets poor execution. A graveyard of shredded tendons and torn muscles.

For a number of years the more historically inclined wishing to preserve the authenticity of an attempted recreation of the art have used cutting as a metric or a gate keeping mechanism to facilitate this end. I'm not going to argue for or against, I'm simply stating a fact. I will note that in my own practice, cutting has taught me a lot about edge alignment and body mechanics, and has proved to be an incredibly useful tool in my understanding of historical martial arts.

Perhaps a better way to frame an argument around the use of of form and body mechanics in fencing, as opposed to what works, is to discuss their purpose.

Simply put, the weight of a historical simulator is greater. As such, the refined and well trained small twitch motions that are so effective with an epee or sabre {obviously an extreme}, will often stress the muscles and tendons that facilitate such motions to such a degree that they could potentiate long-term and systemic injury.

When a historical figure like Johannes Liectenauer suggests that you should fence with the entirety of your body, or the anonymous author of MSS Ravenna M-345/M-346, encourages that a half turn of the hand should be accompanied by a half turn of the body, and a half turn of the body should be accompanied with a half turn of the foot, etc., they're not just teaching you how to fence with leverage and strength, the notion imbued in that conclusion is inherently the functional necessity required to command the weapon at hand.

This is a function of form, and your form should be proportional to the tool in use. A well formed sketch would neither translate to the chisel or brush, just as the form of an Olympic fencer wouldn’t translate to the historical lists.

Alas, while form and technique may bring back echoes of the past and are themselves well calibrated for the reality of the tool in use, they still find their match in the realm of reality. How can it be so?

The Power of Principle:

Background:

In the winter of 2019, I was competing in my third or fourth HEMA tournament (I honestly can't remember), at Queens Gambit in Charlotte NC, and I was fortunate enough to square-off in the final of the sidesword competition with Martin Niggemeier, a veteran fencer who was formerly a member of the German National Olympic fencing team, and a top 50 rated Sword and Buckler fencer in the early days of HEMA ratings. In the quarterfinal I had just beaten my dear friend Zach Showalter, a top 25 rated sidesword and longsword fencer {historically}, while Martin had just dispatched David Biggs, another good friend and tremendous fencer, whose decorated HEMA career is only overshadowed by his legendary status in the SCA. In retrospect it was a stacked field, even if Zach and I were just starting to reach our potential.

Anyone who has ever had the pleasure of fencing with Martin Niggemeier will probably agree that the best way to describe his approach was ‘wily’. As an older gentleman he knew he wasn't going to beat you with pure athleticism; although he was very athletic, and from a technical standpoint I wouldn't say he was among the most historical fencer I've faced in the ring; though he was plenty capable and came from one of the best technical schools in the country—Sword Carolina. What separated Martin from the field that day was his understanding of principle. Tempo and measure.

He won.

It was a close match, but I gained some tremendous experience in spite of the outcome. As all competitors learn, sometimes losing is more formative than winning, and it's the work you put in after a loss that pushes you to realize your full potential.

Boy did I put in the work.

I had the pleasure of fencing with Martin again at SERFO later that year, in a non-competitive sparring match before the sword and buckler tournament. He told me afterwards that our sparring match that day was among the best fencing he's ever taken part of—it was a tremendous compliment. Everything I had worked toward in the lead-up to that moment had come to fruition, and I accounted for myself incredibly well—I dominated him in that final bout.

This, quite rightly gave me significant confidence going into the sword and buckler tournament that day. I rode that high through my pool and cleared my field of competitors without getting hit—once. A perfect pool. Then, I had to face Marcus Lewis in my first elim fight, in the second round of elims after a bye. Marcus had so many doubles in his first elim fight that his coach Keith Cotter-Rielly started him out in our match with a negative score. Despite this, Marcus still won. I was incredibly embarrassed with myself. Mind you, Marcus was no slouch, to the contrary, he's one of the greatest American competitive fencers—ever. He's been in the top 30 of every weapon category he's competed in, and at his peak was the 16th highest rated fencer in the world in longsword. Still, I had an unprecedented advantage—after a perfect pool—and I squandered it.

So what happened?

In my pool I was able to impose my will, and rely on my technical fencing and more robust defensive approach—born from losing to Martin—in order to dominate my matches. When I squared off with Marcus, that proved to be my Achilles heel (pun intended). My technical acumen was stretched to it's limit by Marcus's sheer volume of attacks, and was further hindered by my self imposed limitation on taking a risk that could result in a double, and inevitably cost me a number of points in the end. The technical fencing that had brought me to that point failed in the face of principle.

Later that year I would go on to take third place in sword alone at Raleigh Open, beating Piotr Przanowski; a top five fencer in rapier and sword and buckler, with a very principled and technical approach—born from my loss to Marcus—but just a few months later I would lose to him twice at Steel City in the quarterfinal for sabre; not my discipline, and the final for sword and buckler because I was trying to be far too technical. After riding the plays of Marozzo’s sword and large buckler through my pools and elims; with the likes of Joe Lilly, I made it back to a gold medal match, but I was undone by an ill timed wide step trying to do an action from Marozzo’s sword and targa.

It was an incredible year for competitive success, and a number of key lessons were learned as I gained invaluable experience, but that all illusive gold medal still evaded me. I had to adapt.

As Antonio Manciolino says in his Opera Nova, experience is the mother of all wisdom. What I learned through my success that year, and gained from my loses was an understanding of the limitations of my approach. I was training form almost 10 hours a week, and sparring every time the opportunity presented itself, but my 7 day-a-week commitment still had not produced the results that I was looking for. There was a disconnect. One final hurdle to overcome.

Then the pandemic happened.

I started l’Arte dell Armi to rekindle the lost camaraderie that the COVID-19 virus stole from the HEMA world, and through that I had the honor of talking to some of the best fencers in the world.

It was through those conversations with many of those legends of the game that I began to realize where my approach had faltered. My focus on the technical realization of the historical texts was in many ways missing a key element of purposeful fencing. Principle.

That's when I set off on my quest to master Antonio Manciolino’s Opera Nova, a work still in progress to this day. If you listen back to my first interview with David Biggs, and the subsequent interview where we discussed the stringere of space, you can actually hear my change in mindset; it's pretty fascinating. If I had to credit anyone with inadvertently teaching me how to escape that enduring plateau, it would inevitably be David Biggs, Bill Grandy (in an interview sadly lost to the void), James Reilly, and Richard Cullinan.

What’s In a Technique?

Embedded in every assalto, abatimento, and combattendo—every gloss, device, and play, are a series of principles. Some are often left unstated, like the rules that govern fencing; tempo and measure, while others can be obscured in the presentation of a technique but are ever present; like strong and weak—the two principles that Liectenauer says are the fundament of all art.

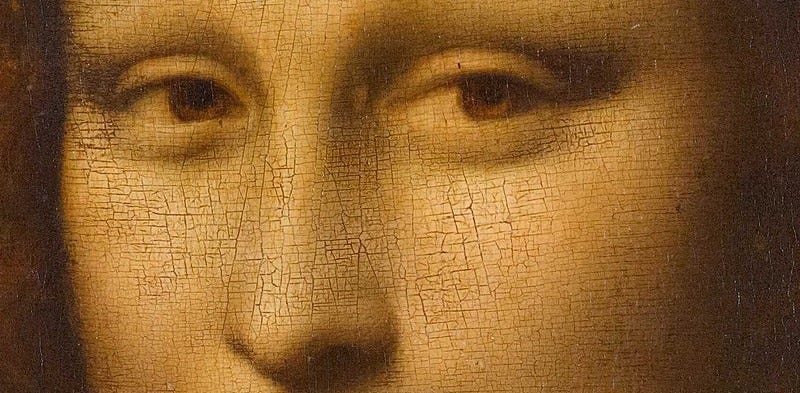

Drawing this back to our analogy of Leonardo da Vinci and Michaelangelo Buonarroti; both men upon mastering their forms and techniques would have been tasked with copying the work of a master over and over, before apprenticing with a master to aid in his work until they were finally charged with creating a masterpiece of their own. It was through this pedagogical process that students would learn the principles executed by the master and eventually develop new techniques and a unique style.

What eventually separated these two men from their peers was a certain je ne sais quoi.

For Leonardo da Vinci this was manifest in a technique called sfumato or more colloquially as Leonardo’s smoke, where he would seamlessly blur the outline of his subjects into the whole of the painting. For Michaelangelo it was his innate ability to convey emotion through the posture of his subjects. They both found a way to manipulate form and technique to manifest a sense of realism—humanity—in their works.

When you look at a technique in a fencing manual, and you attempt to develop an interpretation beyond the letters on a page, the question you should keep asking yourself, is why.

When an author says, if the agent attacks with a you should do b, there are a number of causal realities that could prompt c, which ultimately results in d. But further analysis could reveal what else can be done if the expected response in c is not the reality. The why you’re searching for is imbedded in the patients response, and the agents subsequent action.

The answer to why is often derived as, what is best; this is where many people tend to err. What is best is often suggestive and personal, it requires some experience and lacks a sense of humanity. What is best can help you form an interpretation that works in isolation, but it will often fail to account for variability.

Sword fighting happens at a rate of speed that severely limits analytical conceptualization or computation beyond a fraction of a second. Thus it's application has to be reduced to a function of the senses. This is represented in the Liechtenauer tradition with the word fühlen and the five words {vor, nach, strong, weak, Indes}, it's solved in-part in the Bolognese tradition by watching the opponents sword hand and tempo, and in later rapier traditions by watching the point of the opponents weapon and tempo. Each of these realities are systematized to solve the rapidity of requisite response and are predicated on the use of one of the five senses.

The objective of the interpretation should therefore answer why first, using the principles of fencing to derive why.

Take for example Marozzo’s first abatimenti da spada sola, Capitolo 94. In that section you are agent. Your initial action is to throw a provocation (falso tondo) toward the eyes of the opponent that gets them to react, followed by a blow that's meant to capitalize on that movement (mandritto fendente). Why?

“You should hold it to be a certain factor that no one who is attacked when raising out of a guard, or in falling from a guard, can perform any counter except for an instinctive response as if he knew nothing…But if perchance you were to attack him when he was neither rising nor falling, be advised that he could interrupt your intention with a variety of blows. So if you wish for honor, be attentive, and look to attack him as he rises or falls from his guard with his counters.”

—Marozzo, Capitolo 171; Swanger, pg. 256

You don't want your action, your true attack to be interrupted by your opponent being fixed in guard; whereby they can act in the time of your true attack, so you have to force them to move in some way. That answers our why for a, but what about b and c?

Marozzo doesn't tell you what b is, we’re only given c. So, in order to find a reasonable solution to the missing b it helps to ask, why c. Here our c is a mandritto fendente which ends in porta di ferro larga; a full cut. The question you should ask yourself is why does he do a mandritto and why does he make the cut fendente (vertical).

For me, the answer is that Marozzo is trying to gain measure through a series of provocations with the intent of performing a meza spada action; we can call this the objective. The falso tondo to the eyes provokes a response, and if the opponent defends against a with b and holds their ground to defend against c—the subsequent mandritto fendente—then you've got them at meza spada; our objective.

But I tell you well that there are few people who shine when they are at the said half sword and it is those who understand and know how to enter and exit the said two ways of half sword, for it is they whom I would consider excellent and perfect fencers as they understand tempo, and those who do not understand the above-mentioned art cannot be perfect fencers as they are ignorant of tempo and mezzo tempo. God forbid, when they fence with each other, the occasion arises where one those ignorant fencers will land a blow, as they do not do so with knowledge; but simply through chance, and this is because they are not founded in the art of half sword.

Achille Marozzo, Capitolo 35

The falso tondo goes from right to left (agents perspective), which means their best response is to parry from left to right (patients perspective). If they do so, then the mandritto fendente will either strike their head and sword arm (no d) or their subsequent parry of will create a crossing (d). What is best, is of course subjective, what if they parry from right to left or come forward with an attack of their own?

The answer reverts back to the objective. Say, they defend right to left, their terminal guard will be on their inside {their left}. In this scenario they're likely trying to beat your sword, but that's inconsequential. If their destined position of rest is on the left, then you'll want to gain their sword on the left before giving an attack. Thus, rather than throwing the mandritto fendente, you'll throw a roverso traversatto, which is to quite literally cross their sword; for the unacquainted. Once you've made this change you can proceed as you see fit, according to principle. This is facilitated by watching the opponent’s sword hand. Note, that the objective—gaining the opponent’s sword—has not changed (seeking mezza spada).

There are a number of principles at play in both of the scenario’s highlighted thus far. First is whether my opponent is strengthening or weakening. In both {left to right or right to left}, they are strengthening; going from one guard to another. Therefore, as outlined in the Marozzo quote above, my objective is to renew my attack (weaken; c) before they are settled in guard. The objective of that renewed attack—in tempo—is to create a crossing whereby I can act in an artful manner.

If they come forward with an attack in the tempo of your falso tondo they will be weakening, and you should go strong into it, be it with guardia di faccia or a mezzo mandritto, etc.

As the anonymous author says:

Now having understood how tempi are born from attacks, you will understand that attacks are born from tempi in this way. For it is of great necessity to every person to first recognize the tempo in which you make your attack. Because if you stir or throw an attack without recognizing the tempo, you will not do it well. And though the tempi are born from an attack, nevertheless it is necessary to recognize the situation of the tempo, in particular the situation where you are throwing an attack. Because if you wish to throw some attack without knowing the tempo, you will do so blindly and will be unable to make it well, insofar as it is necessary to first know the tempo and then to make the attack, if you wish to proceed artfully.

—Anonimo Bolognese; Fratus pg. 64

So, when you give that falso tondo, you should be looking for how the opponent responds to the attack, and act accordingly. You should be watching their sword hand.

What's clear from the text, is that the pressure of a and c; the falso tondo followed by the mandritto fendente prompts the opponent to retreat or give ground. This is indicated by the mandritto fendente ending in porta di ferro larga; a terminal position only assumed if the play (progress of the fight) has become wide.

The next two techniques in the abatimento plus the opening offensive action in capitolo 100, form a tryptic that highlights a set of key principles of false edge actions throughout the Bolognese corpus. I like to sum it up like this:

«If it bites; thrust • If it beats; slice • If it breaks; cut around»

In Capitolo 94, Marozzo ends the mandritto fendente in porta di ferro larga where he’s set a trap. If the enemy attacks your head or leg, you throw a falso to the sword hand in the tempo of their attack, whereupon you’ll slice {segarai} a mandritto fendente traversatto, which is basically a vertical cut from the right that crosses, and this cross or traverse is likely across their sword arm (I’ll add clarity to this in a minute). Then you redouble the cut.

The segata indicates that there is a slight beat, a bounce per se, that creates a slight separation of the swords. Not enough of a separation that the opponents sword is off-line so you can't cut around, and it hasn't bound so you can't thrust. Thus you take advantage of the space and slice to the face and sword arm.

Because you're on the outside line with that rising falso and segata, the opponent will have no choice but to parry your attack toward their right {left to right}, which allows you to redouble your mandritto behind their sword to the exposed inside line.

The principles at play here are twofold. One, when you've created an opportunity to attack, make the tempo or size of your attack proportional to the distance from the opponents sword. Two, if they have the wherewithal to parry, redouble or renew your attack in the tempo of their strengthening or guard change. Or as Manciolino says, “He who redoubles his attacks is a valorous fencer.” (Leoni, pg. 115)

The redoublement of that fendente ends in porta di ferro larga. The trap has been set yet again. This time however, when the opponent tries to drive us out of our wide guard, here Marozzo uses the verb caccierà; literally a driving hunt, with either a thrust or a cut, we come up with the rising falso, and because of the magnitude of the corresponding beat and separation of the swords (which has broken the opponents structure; hints break), we can cut around with a mighty roverso that goes from the top of their head all the way down through their toes.

Again, the principles remain the same, but one must admit the repetition seems rather intentional, like Marozzo is trying to convey the principle by replicating the same progression with two very different continuations within the same abatimenti. Almost like he's leading us to the why.

Later in Capitolo 100, from porta di ferro stretta, you meet the opponent’s sword with a rising falso that “bites” into their sword, and come forward with a punta dritta (a thrust from the right). This illustrates the third facet of the principle, where if the swords bind the repost is a thrust.

This same principle is illustrated in Antonio Manciolino's sword alone section found in Book 4, Chapter XII of his Opera Nova.

If he attacks your upper parts with a mandritto or riverso fendente, or with a thrust, you can parry any of these blows with a falso, provided that you do not pass the Guardia di Faccia. Then, immediately pass forward while turning your hand, and push a thrust to your opponent’s face or chest—as you prefer. Alternatively, after parrying with the falso, you can let loose a mandritto to his face and let it descend so that it hits his arms and chest: if you choose to deliver this stroke, accompany it with an accrescimento of your right foot. This is among the unique defenses that can be effected in this type of play.

The alternative here is predicated on the principle of proportionality. If it bites; thrust, if it beats; slice. Notice the specification that Manciolino gives here, that the slice will go to the face and descend to the sword arm, the intent is to make sure that the strike finishes in a way that prevents any sort of counter attack. This is the same technique that Marozzo is illustrating when he uses the term traversatto.

It's worth taking a moment to further illustrate how this technique could help everyone participating in historical martial arts—regardless of approach. Swords are usually classified as such because they have longer blades and therefore more cutting edge to pass through a target. When cutting, even with a simulator of a weapon, the proper mechanic for delivering a cut is to draw the weapon through the target, unless otherwise stated.

What I tend see a lot of—primarily in competitive settings—is percussive or popping cuts {playfully coined as a boop} rather than people drawing their edge through. Consequently, when you strike someone's head and leave your hands high or pull straight back from the target area, you're more likely to double, whereas if you to draw the edge of your weapon through the person's face, you're more likely to cover, and make a more martially valid cutting action in the process. Using a sword like a sword has benefits beyond recreation. Furthermore, the force transfer of a cut that is drawn verses a cut where all the force is localized to one location is far less, and is therefore less likely to cause a concussion or any percussive damage, keeping your sparring partners safe and happy.

Returning to Capitolo 94 and 100, from Achille Marozzo’s, Opera Nova. What we’ve done with this exercise is, we’ve taken a play or set of techniques and extracted a principle that we can use in fencing. The likelihood of getting through the opening provocation of Capitolo 94 and settling yourself in porta di ferro larga to set-up the segata followed by a redoubled mandritto that ends in porta di ferro larga so the opponent comes forward again, only this time to beat their sword away with such vigor that you can cut a mighty roverso from head to toe is unlikely. However, utilizing a rising false edge while having the knowledge and a well trained sense of feeling; where you’ll know whether to thrust, slice or cut around, is much more likely to come into play and is perhaps more useful.

We can arrive at the principle by identifying trends and similarities, then exploring where they differ, whereby we’ll begin our digression by asking ourselves why.

Bringing Technique and Principle into Harmony:

A helpful way to thoroughly explore the texts in both a technical and principled manner is to find a number of different plays in the text that have the same set-up (a-b) and different outcomes (c-d). Identify what stimulus from a or b would prompt the variation of c or d, and build an attack tree. Focus on that principle and develop the correct responses based on the principle at play.

In order to do this you'll have to familiarize yourself with a number of texts. In doing so, keep a notebook, start a page for falso from porta di ferro, and start filling in plays. Look at a number of defensive actions, offensive actions; make spreadsheets, pour over the text and start building a technical bank where you can look for how an author of a set of authors apply certain principles.

Keep asking yourself why. Look for the all valuable or and explore the nuance of the potential variability.

This function, when put into practice, will help you to fence technically with proper principle, which is vitally important. It's the sfumato, the emotion, the chiaroscuro—the sprezzatura—that makes this practice an artform.

As you find the principles that instantiate the art, bring them into your form practice. Do an assalsto or an abatimento and explore how the structure and dynamic movement of the authors bring the principles to light. This will help you train a martial body and a martial mind-set, it will help you train the neural pathways and decision making process necessary to calculate while the sword is moving. It will breath life into your sketches.

Here are the principles I look for:

Is it an attack or defense?

If attack:

Is it a provocation?

Is it a true attack?

If defense:

Is it contra tempo?

Is it due-tempo?

Does the role of attacker or defender change in the progression of the play?

Is the opponent's response strong or weak?

Weak: cutting around, sfalsata, impuntato, wrenching, thrusting free etc.

Strong: trying to complete a guard change; parry, overbind, contratempo, etc.

Is the authors response strong or weak?

What is the measure?

Bolognese fencing has different tactical realities predicated on measure; larga, stretta, mezza spada.

Where are you in the progression?

How does measure change your response? Is the author giving different responses based on a change in measure from either agent or patient?

How does this happen in reality?

ie. If I attack my opponent or provoke my opponent, I am still beholden to the notion that I want to renew my attack in the tempo of my opponents guard change before they become fixed in guard. So, how do time, tempo and principle change the execution.

Am I seeing a trend of variation, and can I extract a principle from that variation based on the above criteria?

Commonality. Does this action show up in other sources?

If so:

How is it similar?

How is it dissimilar?

If dissimilar, what about the guard or expected response could be different that would cause the author to deviate.

Building your training around tactical progressions will help you account for inevitable variation. That is, you'll have knowledge of progressions along the different branches of the tree of possibilities. Some authors like Antonio Manciolino already present their techniques in this way. Take for example his sword alone section. You stringere your opponent with a gathering step, constraining the space, and trapping the opponent in a low guard; where their only natural attack is a thrust. When they come forward with the thrust you’re given a counter to their initial attack; a rising falso from porta di ferro stretta that doesn’t go past guardia di faccia, and five potential secondary attacks from the opponent, which he concludes with two counters if they deliver a cut from a low guard.

A few mechanical issues I would fix in my presentation here aside, you can see the variation and the principle of each progression.

This is what makes Manciolino and dall’Agocchie great sources to start with, they provide a very linear systemic approach, a and b; c and d, are clearly defined. A trickier source—like Marozzo—isn’t as concise. Thus it's often better to work from a source that is more clear, determine the principles, and work your way into an author like Marozzo, so you have a solid foundation.

While Manciolino is technically more concise, he’s not always clear which principles are at play. Note that in developing that interpretation I had to rely on a number of rules that Manciolino outlined in the opening chapter of his Opera Nova, and further justified those principles with passages from other authors like Marozzo.

Interestingly, Marozzo does recommend a similar pedagogical approach as Manciolino and dall’Agocchie, he just doesn't bother to work through it like they do. In book two of his Opera Nova, Capitolo 138-143, he takes you guard by guard and tells that you teach your student how to attack and defend from each guard position. This seems relatively out of place given the fact that he's already presented the bulk of his combattendo and abatimento with sword and various defensive arms at this point. Thus the general repudiation that he needed a better editor.

However, I think this might be intentional. You've already shown your students the tactical modes of fencing through the assalti, and given them an idea of how to move in each passage of measure, then through the abatimenti and combattere, you’ve illustrated how to weave these elements together; how to traverse the modes and measures, and apply it to the reality of an opponent, where finally you bring your students back to the principles and variation of position. This leads to that ‘ah ha’ moment, where the principle enters their mind and substantiates the preexisting knowledge of the techniques.

Perhaps that's just wishful thinking.

Regardless, your development of interpretations should follow a similar progression.

Technique:

Biomechanics

Physical aptitude

Technical application

Principle:

Why

Strong and Weak

Tempo

Mode/Measure

Structure

One thing I see a lot from more principled interpretations to make a play ‘work’ is the vaunted ‘unstated action’, or deviation of steps or actions (cut angulation, structure, guard form and the like) to make their desired interpretation come to light. Ultimately, if you're seeking the truth, this is a practice to be avoided. But…

Sometimes you don't have a choice. So how do you you square that circle? You've gotta grind the edges. What does that mean? More often than not, the author or a tangential author will give you the answer elsewhere in the text. You're going to have to do some digging, really look at the fullness of the text or system to find an answer.

In the video embedded above, I used a few common pieces of advice found throughout the Bolognese corpus: Marozzo and Manciolino both advise that you should watch the opponents sword hand until your close enough that your attention should turn to their left hand, and that the only natural attack from low guards is a thrust.

Through those unstated principles, I was able to devise an agent and patient that each had a chance for success, and furthered the play along as Manciolino described them in his text. I also stuck to Manciolino’s stated actions; ie. steps, cuts, parries, guards etc. and tried to find the body structure, and turns of the hips that allowed me to perform the techniques effectively.

All that to say, sometimes there is a grey area in the overall presentation of a play, but those grey areas should be colored with evidence found within the text or related texts:

Here's a helpful progression that I learned from Greg Mele; though this is my take on his spheres of influence. When you need to find the correct action to fill-in the blank look first…

Within the same section.

Withing the same source.

Within the same system/timeframe. A reasonable progression for the early sources would be:

Marozzo and Manciolino (early 16th century)

Anonimo and dall’Agocchie (late 16th century)

Viggiani

Achillini

The Bolognese corpus writ large.

Within the same time period/region.

Within an earlier text; eg. Fiore or Vadi for Marozzo spada da due mane.

Within later sources.

Globaly.

While not perfect, this progression will generally bring you closer to the reality of what you're trying to to recreate.

Conclusion:

Whatever your objective may be, engaging with the sources in a meaningful way is always a rewarding enterprise. For the beginner, it can be intimidating at first, like you're reading another language, but just as in the process of learning a new language, the best place to start is with the essential vocabulary. As you get more familiar with the texts, and the cadence of the various authors, reading through the source material will get easier with practice.

For the more experienced practitioner finding the correct balance of principle and technique can do wonders for your fencing overall. In many respects—for me—a more principled focus in combination with my preexisting technical knowledge-base and my dedication to form practice allowed me to overcome many of the hurdles that were holding me back, ie. I started to win gold in most of the competitions that I was taking part in. While this was a slight departure from what I thought was the right way to approach historical fencing, what I found was something closer to what the Bolognese authors intended. My intent was no longer to see my way through the progression of an abattimenti hoping that my opponent would play along or expecting that my action would force the response I was looking for, but to use the bones of those well conceived progressions to dominate my opponents through the principles they represent.

The more principled fencer can find value in this as well. While a well trained sense of the rules that govern fencing can take you far in Historical Martial Arts, learning to understand the body mechanics and looking at the systemic principles inherent in the pedagogy of the historical authors can help you problem solve new and unexpected stimuli. For example, I watched a video from a rapier practitioner the other day, where the person presenting a technique was disparaging the fact that they hated beats, because they never work. The principle we explored with Marozzo and Manciolino’s sword alone sections could greatly benefit this person. If it bites thrust, if it beats slice, if it breaks cut around. You can modify that at your leisure to find how the same principle inherent with the weapon at hand. I’ve found a number of instances where the principle applies in KdF as well.

My hope is that you’ll use this framework, or some variation of this framework to pursue an artful expression of Historical Swordsmanship. Find value, purpose and function in the persistent pursuit of perfecting form, seek the sfumato and humanity of otherwise inanimate splotches of ink on a page, and breath life into the words of the ancient masters. Through this enterprise, you can find—I believe—a sense of mastery yourself. While we don’t have masters in the modern age of HEMA, the pursuit of mastery should always be your goal—even if the objective is in many ways unattainable.

In the end, you’ll have to pursue whatever means bring you closer to your ultimate goal. I just hope this acts as a source of encouragement for those seeking a way to either find a more substantial exploration of the texts, or a starting place for those are beginning the endeavor. In many ways this is a letter to my past self. I hope you find it useful as well.

This is the beginning of a series exploring Bolognese tactics. Both Stephen and I will be posting a number of articles in the near future, expressing our understanding of the tactics, strategies, and technical elements of Bolognese fencing we’ve found in our years of practice. If you want to follow along, make sure to subscribe.

Works Cited:

Fratus, Stephen. “With Malice and Cunning: Anonymous 16th Century Manuscript on Bolognese Swordsmanship.” Lulu Press. 18 February 2020. Print.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Duel, or the Flower of Arms for Single Combat, Both Offensive and Defensive, by Achille Marozzo.” Lulu Press. 22 April 2018. Print.

Leoni, Tom. “The Complete Renaissance Swordsman: Antonio Manciolino's Opera Nova (1531)” Freelance Academy Press. 27 May 2015. Print.

Swanger, Jherek. Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Dell’Arte di Scrimia, “The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation”, lulu press, May 5, 2018. Digital.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Schermo of Angelo Viggiani dal Montone of Bologna.” 2002. Digital.

Swanger, Jherek. “How to Fight and Defend with Arms of Every Kind, by Antonio Manciolino.” Lulu Press. 4 February 2021. Print.

Fratus, Stephen. “The Monomachia: The Fencing System of Francesco Altoni.” Art of Arms Press. 1 September 2024. Print.

Termiello, Piermarco & Pendragon, Joshua. “The Art of Fencing; The Discourse of Camillo Palladini.” The Royal Armories. October 2019. Print.

Thanks to Moreno dei Ricci for the clarification on this.

I watch your "Manciolino's Sword Alone" video from time to time before training. It helps to get a refresher on form, and visualize what I want to try during sparing.