Time—the 4th dimension.

Whether you’re practicing Kunst des Fechtens, Armizare, the Bolognese tradition, plays from MS. I.33, or you’re just doing modern sport, time (timing/tempo) is an essential element of the art you practice. But what is a tempo, and did the concept really exist in a medieval context (i.e., I.33, Armizare, or Kunst des Fechtens)? Or was it a Renaissance creation? Can we effectively communicate time across generations, and create a unified concept of tempo?

Let’s find out!

The concept of time is largely rooted on the movement of celestial bodies. One full rotation of the earth is one day; one full rotation around the sun is one year. This has remained true for the majority of human history—though which body was rotating around which was often misunderstood. Despite the general consistency, this methodology of measuring time had one noticeable flaw: the minutiae of an object in motion over the course of [what we would call] a few seconds was on a scale so small it was almost impossible to measure using cosmic bodies.

Enter Aristotle.

In his attempt to create a philosophical model to chart objects in motion, Aristotle became one of the first western thinkers to devise a system of measurement or system of counting used to describe time and the motion of an object. This system we now associate with the principles of physics, which takes its name from his work on the subject: Φυσικὴ ἀκρόασις, Phusike akroasis, or Physicus—natural things or simply nature.1 Time is defined by Aristotle as “a number of change with respect to the before and after.” (Coope; pg. 219)2 Or, to paraphrase Angelo Viggiani’s muse Bocadiferro explaining Aristotle's principles, the movement between two points of rest.

Aristotle’s observations on the physics of the universe would eventually succumb to the scientific rigors of thinkers like Kepler, Copernicus, and Galilei, yet it persisted as the standard until Sir Isaac Newton put the final nail in the coffin in 1687.3

Therefore, when we talk about tempo, indes, etc. we have to do so through the lens of Aristotelian physics. No source does this better than the aforementioned work of Angelo Viggiani. However, before we delve into Viggiani and other 16th century authors like Marozzo and Manciolino, I want to highlight the development of the illustration of tempo in fencing manuscripts from the earliest known sources up to the 16th century. This will help us to solidify our understanding of tempo, and demonstrate how these sources depict the same Aristotelian understanding of physics explained in Angelo Viggiani’s, lo Schermo, written in 1551.

It's important to note that just because the word tempo was not explicitly used by the KdF authors, Fiore, or the priest(s) who wrote MS. I.33, that doesn't mean that tempo was not observed, illustrated or understood. To the contrary, this piece will seek to reconcile this common misunderstanding and show how the Aristotelian concept of time that we see codified by later 16th century authors—which still exists in the modern conception of the term—is presented in the works of its 14th and 15th century predecessors.

What is a Tempo?

Authors across the centuries have found a number of different ways to convey the concept of tempo. Some are more verbose than others, while a number are quite pedantic—some are borderline scientific, and others are more vague. One of the best explanations comes from Nicoletto Giganti. This is in part because he starts with a detailed list, then course corrects, and drops a succinct statement that perfectly sums up the concept: “…In every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita {person}, such as changing guard, is a tempo in the way that all these things are tempi—because they contain different intervals.” (Giganti; Vansteenkiste, Wiktenauer)

And the Anonymous author gives us a rather indisputable rule:

(I)t is the movement of the sword that creates a tempo, and these tempi come from the attacks of the sword. Thus, as soon as you move your sword you will give birth to the tempo it creates. (Anonimo; Fratus; pg. 64)

While this is nice and easy—that every movement of the sword, body, foot, or changing of the guard is a tempo—what’s the correct tempo? That is, what's the correct tempo to start an attack? Not all tempos are created equal. Giovanni dall’Agocchie gives us a list:

When you have made a parry.

When their blow goes past.

When they raise their weapon to attack.

When they injudiciously change guard.

When they take a step.

But let’s table this discussion until after we talk about the medieval sources. We’ll take the Anonymous Author, Giganti, and dall’Agocchie at their word, as they provide a concise framework and include more modern observations as they fit the discussion. Then, when we’ve clearly outlined the 16th century discussions of tempo, we’ll revisit the plays of their medieval counterparts, and draw a conclusion summarizing what we've learned.

The Medieval Sources

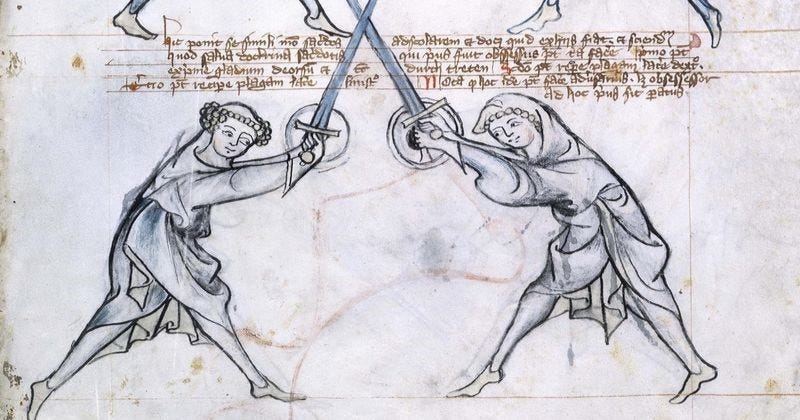

MS I.33

For those unacquainted with I.33, here are some terms and definitions that will help you follow along with the subsequent discussion.

Terms:

Wards or Custodia, and Obsessione: Guards or Postures

(1: Under the arm (sub brach)

(2: Right shoulder (humero dextrali)

(3: Left shoulder (humero sinistro)

(4: Head (capiti)

(5: Right side (latere dextro)

(6: Breast (pectori)

(7: Langort (Longpoint; may be either a custodia or an obsessio)

Halpschilt ('Half shield', one of the obsessiones)

Krucke ('crutch', a defensive position)

Albersleiben (possibly the fool's guard position)

Vidilpoge ('fiddle-bow', a specific custodia)

Actions of the Sword and Buckler

Durchtreten, durchtritt ('stepping through')

Nucken ('nudge', a specific attack)

Schiltslac ('shield-blow' or shield strike)

Schutzen ('protect' or parry)

Stich ('stab' or thrust)

Stichschlac ('stab-blow')

In the first play of I.33 we have the scholar assume one of the two counter postures to an opponent presenting in first ward, halbshilt. The priest attempts to displace the scholar’s sword with an outside bind. Here the scholar will counter bind and enter (threaten a low thrust, or stich) to perform a schiltslac.

This is the tempo.

If the priest misses this tempo the scholar performs the schiltslac and strikes the priest in the face with his sword.

However, if the priest is wise of his options—dirchtritt, mutation of the sword, or wrapping his right arm over the scholar’s sword and shield—and acts in the moment—in tempo—he will successfully counter the scholar’s attack.

Next, we have a different approach—6th Ward (pectori) vs. halbshilt—where the priest will attempt to thrust or stich the scholar, driving his sword up to the sign of the cross—to the hilt. The scholar will bind, and deflect the thrust down, which brings us to our tempo. If the priest is unable to act, the scholar will schiltslac as before, but if the priest acts in tempo he has the durchtritt, mutation of the sword, or wrapping his right arm over the scholar’s sword and shield all available to him. Here we will see the sword and shield wrap, and a counter to the wrap from the scholar.

This tempo is everywhere in I.33, so let's look at a different one—for the sake of completeness—before we move on to Fiore. In the next sequence we’ll see the priest start in 2nd Ward (humero dextrali), while the scholar will counter or perform a shutzen {parry} in halbshilt.

This is our tempo

When the scholar has performed the shutzen, he is granted the initiative of a counter attack. As the author says, “And you must know that (according to the true teachings of the priest) he who was the first to displace, can do three things: firstly, he can push the sword downward and then durchtreten; secondly, he can execute a blow from the right side; thirdly, he can execute a blow from the left side. Note that the opponent can do the same, even though the displacer is the first to be ready.” (I.33; Bachmann, Wiktenauer)

In the illustrations above, the scholar—having performed the shutzen—will perform a durchtreten to the right side of the priest’s face. If the priest is aware of this, he will “deflect the action mentioned above while the scholar is still underway.” (I.33; Bachmann, Wiktenauer) Thus, with the priest having depressed or driven down the scholar’s sword, we see his pupil returned to our old familiar tempo and—schiltslac!

As we can see from the highlighted plays, the priest(s) who wrote MS I.33 were well aware of tempo, though not stated, illustrated, explained, and described. While only the second set of plays takes advantage of the initial tempo with the shutzen and counter attack, many times the correct tempo is born in a moment where you can gain advantage and control your opponent’s weapon, as we see in the first set of highlighted plays.

Referencing our shortlist of tempos above, I.33 illustrates the first of Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s tempos of attack—when you have made a parry—with the second set of actions {shutzen}, and demonstrates principles of Nicoletto Giganti and the Anonymous author’s advice with the first set of actions (the three options). Furthermore, if we add in one more anecdote from the Anonimo, we can inject a bit of nuance to the wisdom of the priest’s instructions. The Anonymous author continues his discussion of tempo by saying, “Because if you wish to throw some attack without knowing the tempo, you will do so blindly and will be unable to make it well, insofar as it is necessary to first know the tempo and then to make the attack, if you wish to proceed artfully.” (Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 64)

The first set of plays highlights this beautifully. Were the priest to pursue his outside bind with no clear understanding of the potential schiltslac waiting for him, or the three potential counters to the setup of the schiltslac, he would be undone. However, if he is aware of the tempo he’s rendering, and how his opponent will seek to leverage it to their advantage, then he will be the first to act and find the correct tempo to attack.

Fiore de'i Liberi

For those unacquainted with Fiore, here are some terms and definitions that will help you follow along with the subsequent discussion.

Terms:

Guards of Fiore:

Posta de donna

Posta de donna destraza, pulsativa

Posta de Finestra instabile

Porta di ferro mezana, stabile

Posta longa, instabile

Posta frontale ditta corona instabile

Dente di cenghiaro stabile

Posta breve stabile

Posta di donna la sinestra, pulsativa

Posta di choda longa stabile

Posta di Bichorno instabile

Posta di dente zenchiaro mezana, stabile

Actions of the Sword:

Colpi Fendenti: Downward blows

Colpi Sottani: Rising blows

Colpi Mezani: Middle (horizontal) blows

Le Punte: Thrust

We’ll kick this off with Fiore’s third master of the sword in wide play. This play begins with the opponent cutting strongly, like a peasant4 or a villain (colpo del vilano). That is, their blow will be full and will not end with their point on-line. Here, utilizing the tempo of their attack, you’ll step to their right (your left), and allow the point of your sword to hang, redirecting the momentum of your opponents blow away from you, while allowing yourself control of their outside line, cutting a fendente to their head or across their arms. If the opponent attempts to attack your legs in the time of the colpo, you'll slip the leg and throw a fendente to their head.

With the first three masters of wide play, Fiore gives three specific crossings. The first crossing is at the tip of the sword, the second is at the middle of the sword, while the third is in response to an opponent striking at a deep target on their first intention (i.e., the peasant blow) and is instead redirected.

The tempo here is born from the opponent making no attempt to find your sword or create a crossing on the sword, like the one we saw by the priest in I.33, and simply cutting to wound. This is dall’Agocchie's tempo of a blow going past. Unsurprisingly, this same action shows up numerous times in Marozzo’s spada da dui mani section (Marozzo’s guardia di entrare with the spada dui mani), with a variety of different set-ups, usually provoked by letting the sword fall into porta di ferro larga, encouraging the opponent to cut strongly at the head.

Turning back to the second master of the sword in wide play, where the weapons cross at the half sword (mezza spada): here the scholar is instructed to either strike down across the arms, or to seize the blade with their left hand, as is demonstrated here.

Once the sword is captured, before the opponent can wrest it free, the scholar is charged with striking with a cut or thrust, or destroy(ing) [their] leg…by stomping with [your] foot against the side of his knee or under the kneecap (Getty; Hatcher, Wiktenauer)—in typical Fiore fashion. These progressions are all predicated by the resistance rendered by the opponent on your blade.

Next we’ll examine the first master of the narrow play. First, notice the crossing: rather than at the tip, or the half sword, the master is crossed below the half, and here he has his right foot forward indicating that he’s stepped-in either in the parry or the blow.

From this deeper crossing Fiore says that, “(t)he play is given to whoever knows more and is swifter.” (Pisani Dosi; Chidester, Wiktenauer) This is advice we see echoed by the Bolognese masters in their mezza spada sections. The reason for this is simply that the left hand becomes a threat, as we’ve illustrated throughout this section on Fiore.

In this progression we see the scholar respond to the deep crossing by either seizing the opponent’s sword between their hands (on the handle), or gripping the outside of the oponent’s arms and smashing their teeth in with the pommel.

Fiore outlines the difference in the two actions. First the opponent comes to the mezza spada and does nothing: “I would strike, and I will hold your sword; restrained by no (p)ledge, you conduct yourself so disgracefully”, or if they knock or push your sword aside, opening to their outside line: “I strike to your face using this hilt, obviously ferocious. This because you had knocked the sword using the deepest touch.” (Paris; Brown and Garber, Wiktenauer)

It's important to note that doing nothing is a tempo rendered at the half sword. What we can see here is that—just as in I.33—we’re drawn back into the tactics of the Anonymous author, in that, “if you wish to throw some attack without knowing the tempo, you will do so blindly and will be unable to make it well.” (Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 64)

What we can decide from this foray into Fiore is that tempo is still paramount. While the master notes that these plays can be done attacking or defending, both modes of attack are predicated on either a well-formed defense followed by counter attacking, or controlling the sword with a crossing and responding based on the opponent’s movement in response. This leads us back to Giganti’s succinct delineation, “it is the movement of the sword that creates a tempo, and these tempi come from the attacks of the sword.” (Giganti; Vansteenkiste, Wiktenauer)

In truth, Fiore’s predilection toward basing his larga and stretta sections on the depth of the crossing is a trope we see played out time and again in the Italian fencing corpus. It's this author’s opinion that Fiore would find commonality with the KdF glosses, any of the Bolognese masters in the 16th Century (unsurprising, considering Lancellotto Beccaria, his protegee, helped train the militias in Bologna) and would probably really enjoy the works of Sandro Francesco Altoni and—wait for it—Salvator Fabris, Niccolò Giganti, and Rodolfo Cappo Ferro. As you'll see in our discussion of obligare and counter guards in the conclusion.

Kunst des Fechtens

For those unacquainted with KdF, here are some terms and definitions that will help you follow along with the subsequent discussion.

Terms:

Vor: Before

Nach: After

Indes: In between, inside, within or during

Schwech: Weak

Stark: Strong

Shlag: Strike

Guards: Hut & Vier Leger

Hut: Guard

Pflug: Plow; middle guard, held left or right

Ochs: Ox; high guard, held left or right

Alber: Fools guard, low point down

Vom Tag: From the roof, at the shoulder or above the head—ready to strike.

Longpoint: Point directed at the opponent, hands about the middle of the body with squared hips.

Actions of the Sword:

Oberhau: Strike from above

Unterhau: Strike from below

Sheilhau: Cockeyed strike;

Scheitelhau: Peak strike;

Twerhau: Cross Strike or Thwart cut;

Zornhau: Warth strike;

Krumphau; Crooked strike

Ort; point; used as a modifier to denote a thrust {Zornhau ort}

Stich; Stab or thrust

Let’s start this off with addressing the elephant in the room. Vor, Nach; Strech, Scwech, Indes: a number of change with respect to the before and after. There is perhaps nothing more Aristotelian than these five words. As the texts tell us:

First mark and remember that Liechtenaur’s /Fencing is aligned at the Five Words / Vor , Nach, Schwach , Stark, Indes; these are the / principles and the fundament of all fighting…

…The five words of Liechtenauer are describing qualities in opposite categories. This is based on the philosophy of Aristotle.

—3227A; 64r-65r (Kleinau; Talhoffer Blog)

Vor is the before, it's used to denote advantage. Nach is the after, and is used to denote when one is behind in tempo, i.e., they are defending or parrying or weak compared to their opponent. Indes is within or during and is used to denote a moment or tempi when the opponent moves to reclaim strength or weakens to cut around. Just like we saw with Fiore, tempos arise from motions of the sword, in the KdF tradition, the initiative or Vor is gained by forcing the opponent into a weak position (sometimes a parry, sometimes a disadvantageous bind), whereby you can manipulate the crossing and the tempo rendered to proceed with an attack. Actions discussed in the Nach are meant to regain the initiative by reclaiming strength, though the term Nach is used as an adverb to denote a consecutive action that follows the termination of the initial blow as well.

We can see a similar principle of tempo, that's outlined by the words Vor and Nach, used in chess, where time is defined as a turn, and one gains tempo, “(w)hen a player achieves a desired result in one fewer move,” and “conversely, when a player takes one more move than necessary, the player is said to ‘lose a tempo’. Similarly, when a player forces their opponent to make moves not according to their initial plan, one is said to ‘gain tempo’ because the opponent is wasting moves. A move that gains a tempo is often called ‘a move with tempo’.” (Wikipedia; Tempo)

This gives rise to the five cuts (fünff hewe/meisterhau {Meyer}) of the Liechtenauer tradition. They can steal back the initiative, the Vor, or gain tempo, by achieving a strong position.

Zornhau Ort:

When your opponent cuts at you with an oberhau, you respond with a wrathful hew, or Zornhau, and then shoot the point toward their chest. “By this, Liechtenauer means that when someone begins to cut over you, counter it by cutting wrathfully in and then firmly shoot your point against them.” (3227A; Trosclair, Wiktenauer)

Twerhau:

The twerhau is also used to reclaim the vor: “when you cut across correctly, you counter and defend against everything that comes from above (meaning the high cuts and whatever else goes downward from above).” (3227A; Trosclair, Wiktenauer)

Shielhau:

So too does the Shielhau: “And this cut breaks that which the buffalo, that is a peasant, might strike down from above as they tend to do. (Just like the crosswise cut breaks this as well, as was written before).” (3227A; Trosclair; Wiktenauer)

The actions outlined are all done in contratempo or mezzo tempo.

Contratempo interrupts the opponent’s tempo, or happens in the time between the opponent’s starting destination and their final destination or guard position (often longpoint). Mezzo tempo means that they are smaller actions than the tempo of the opponent’s attack; they are half time. While the five hews can be used as Vorshlag, to “break” guards, the precept of achieving the vor is still predicated on the advantage of a strong position in relation to your opponent.

The tactical necessity of these devices is outlined by Liechtenauer’s assertion that the person striking the Vorshlag has initiative—which they do—and these specific hews reclaim the initiative by both attacking and defending in tempo.

For with this skill or with this advantage, it often happens that a peasant or someone unlearned strikes a good master by it because they execute the Vorschlag and boldly storm in.

Because however briefly the Vorschlag is overlooked, the opponent hits Indes and they wound and kill in this way. Because if you focus on the blows and will attend to the defense of them, you are always in greater danger than the one who attacks you and wins the Vorschlag.

3227A; Trosclair, Wiktenauer

It’s important to note that concept of initiative is not unique. While some authors disagree on which mode of tempo is best to find your counterattack (i.e., contra tempo, dui tempo, mezzo tempo, etc.), all of them outline devices dependent on these principles, with the objective of gaining a strong position.

As Liechtenauer was aware, you may want to be the first to strike, but that doesn’t always mean you will be. In the later Italian and Imperial fencing traditions, this idea of initiative is known as obligare, or obligation, or putting the opponent in obedience.

The parry partakes of the nature of fear, for he who did not fear some disadvantage, would not put himself on the defence which we may call obedience and subjection, all the more so when it is forced. He who does not wish to be hit is forced to parry. When we can put our adversary under this obligation, we consider it a great advantage, for while he is under the necessity of parrying he may be hit in the line he uncovers by his movement, so that his defence proves vain.

—Salvator Fabris (A. F. Johnson, Wiktenauer)

The Vorshlag and Nachschlag

Now to conclude our brief discussion of the Liechtenauer tradition, we will examine the concepts of Vorshalg and Nachschlag.

“That's why Liechtenauer says: "The Before, The After the two things, etc". Because if you execute the Vorschlag, whether you hit or miss, you then always execute the Nachschlag in one fluid motion, swiftly and quickly so that the opponent cannot come to blows with anything and you shall orchestrate it in such a way that you always preempt the opponent in all situations of fencing.”

—3227A (Trosclair, Wiktenauer)

Here, Liechtenauer says that the Vorschlag must be followed with a Nachschlag, whether the attack succeeds or fails. In the northern Italian tradition this is known as redoublement. Note that tense and definition slightly shifts here. The author, Pseudo-Hans Döbringer, uses both forms of the verb, one that denotes its place in time and one that denotes initiative. The Nachschlag is the follow-on action, drawing back to the precepts of Aristotle, that the time between the before and after has elapsed, and the position is now in the after of the Vorschlag, thus it is a Nachschlag.

{For this next part Vor and Nach; capitalized and in italics will denote initiative, and vor and nach; lowercase and emboldened will denote time.}

A good way to think about this is that one claims the Vor by striking first. The action of the sword still follows the path of time, where it is indes, from the vor to the nach. The follow-up strike, or nachschlag, should happen in continuation of the Vorschlag at its completion (whether it hits or misses); i.e., when it has come to the nach. Prior to this, the path of the Vorschlag may be interrupted—indes—by the opponent (with the five hews, let’s say), whereby the the Vor shifts to the opponent, in which case their nachschlag (redoublement) will be in the Vor.

The conduct of the Nachshlag is determined by the other two words, strong and weak, where you will use fuhlen, and act Indes according to quality of the engagement.

“If you are obligated to not execute the Vorschlag, you always have the Nachschlag available in the sense and in the spirit that you are always in motion and do not either dawdle nor hesitate with anything. Rather, you always conduct one after the other swiftly and quickly, so that the opponent cannot possibly come to anything.”

—3227A (Trosclair, Wiktenauer)

In this context, we see that the speed at which one reacts with the second action (nachschlag) is paramount. At this we can shift back to the supposition of Fiore and I.33. Whereby I am again obliged to be the first to react whether in the Vor or Nach, offense or defense, based on the crossing of the swords, and I would be remiss not to remind the reader of the anonymous author’s wisdom, “Because if you wish to throw some attack without knowing the tempo, you will do so blindly and will be unable to make it well, insofar as it is necessary to first know the tempo and then to make the attack, if you wish to proceed artfully.” (Anonimo; Fratus, pg. 64)

How you proceed, again, is of course determined by the two words, Schwech (weak) Stark (strong); which is the Aristotelian concept of the quality of opposites, as Pseudo-Hans Döbringer points out.

Once more, this a principle we saw outlined in Fiore, where if the opponent comes to the crossing of the swords and does nothing: “I would strike, and I will hold your sword; restrained by no (p)ledge, you conduct yourself so disgracefully” (Getty; Hatcher; Wiktenauer), or if they knock or push your sword aside (strong; Strech), opening to their outside line: “I strike to your face using this hilt, obviously ferocious. This because you had knocked the sword using the deepest touch.” (Getty; Hatcher; Wiktenauer)

Children of the Renaissance

Literacy in Italy from the 15th to the 16th century rose from 15% to 18%. For perspective, in 1451 literacy in Holy Roman Empire was at 9%, the Kingdom of France was at 6%, England was at 5% and Spain (the Kingdoms of Aragon and Castille) was at 3%. By the turn of the 16th century those countries started to catch up, with the Kingdom of France climbing to an astounding 19%, while the Empire and England reached a respectable 16% and the now Most Catholic Monarchy (Spain) remained at a staggering 4% by 1501.5

In university cities like Bologna, Padua and parts of Rome, literacy rates were much higher. To illustrate, at the beginning of the 16th century Florence had 2-4 grammarians teaching primary school education on the rolls of the city government; Bologna in 1385—a century earlier—had 2-3 per district (9), by 1439 they had 4 per district (16), 8 per district in 1480 (32), and 12 per district by 1489 (48), all funded by the university.6

The typical education in the common Latin primary schools looked something like this: Guarino di Verona’s Regulae, Cato, Ovid, Vergil, Cicero, Caesar, Macrobius, Homer, and of course Aristotle.7 I should note that much of the Greek and Aristotelian education really came about in the later years of students’ development, and most of the Aristotelian corpus was reserved for the university level.

In the 13th and 14th century Aristotle’s works saw many of their ethical and philosophical principles challenged. In France his corpus was periodically banned (especially in Paris where students murdered each other in the streets over academic disagreements over his material, and the utility of Averroes), yet in spite of the ecclesiastical controversy that followed the philosopher’s work, for much of Christian world his ideas of Physics and Mathematics remained a less controversial standard.8

As education improved, and more cities began to take the matter more seriously, the deeper ideals of the early humanist education started to slip into fencing treatises. The first author we see take a stab at this is Fillipo Vadi.

Fillipo Vadi

For those unacquainted with Vadi’s work, here are some terms and definitions that will help you follow along with the subsequent discussion.

Terms:

Largo: Wide distance; requires a step to strike.

Mezza Spada: A middle distance where the swords cross.

Stretto: Grappling distance

Mezzo Tempo: A half tempo, comes from the wrist.

Guards:

Posta Sagitaria

Posta di Corona

Posta di Flacon

Posta di Vera Sinestra

Posta Frontali

Posta Breve

Posta di Donna

Posta Lunga

Posta di Cingiaro

Porta di Ferro Terrena

Porta di Ferro Forte

Posta di Denti Cinghiare

Actions of the Sword:

Fendente: A descending cut; from the right or left.

Rota: An ascending c cut; from the right {true edge} or left {false edge}.

Volanti: Horizontal cut; from the right {true edge} or left {false edge}.

Punta: Thrust

Vadi is the first extant source that we are aware of that discusses tempo. It’s important to note that all of the evidence we have of a potential Filippo Vadi in the historical record points to a man who was highly educated. The minted coin with his likeness in the Estense Library digital archive says that Filipo Vadi was a doctor of Medicine. Similarly, there is record of a Philippo Vadi, who served as the governor (Podesta?) of Reggio under Leonello d’Este until his death when he became the councilor for Borso d’Este from 1452 to 1470.9 There is little doubt that Leonello and his half brother Borso would’ve been raised with the teachings of Fiore di Liberi, and the manuscripts dedicated to their father Niccolò III d'Este in their knightly training, and together they provide a compelling set-point for Filippo’s exposure to Fiore’s teachings.

According to the FFAMHE, Filippo Vadi’s brother Lodovico served under Niccolò III d'Este as a military commander and was given the title Potente, or the powerful, circa 1440.10 Given his role, Ludovico eventually moved to Ferrarese territory (Santa Maria in 1440, then San Ilario d’Enza in 1457) with his brother Filippo and their families. In 1445 Filippo became the governor of Reggio.11 Around 1457, while Vadi was serving as a councilor to Borso d’Este, he had a coin commissioned with his likeness, the front bears the title PHILIPPVS DE VADIS DE PISIS CHIRONEM SVPERANS, or Phillipo Vadi of Pisa, dominating Chiron, which the FFAMHE relates, “In Greek mythology, Chiron is an immortal centaur, a great physician, also versed in music, divination and hunting. This tells us that Philippo Vadi was a physician renowned for his skills.”12

The reason why Vadi’s background and education are important is because they render a window into the unseen for treatises like Fiore di Libre. In this article I have implied the presence of tempo as it relates to the images present in the text, but here we have a third generation student of the master’s system (through their constituents: 1.) Niccolò III d'Este, 2.) Leonello or Borso d’Este, 3) Filippo Vadi) relating the master’s work in a modern context with an early Renaissance education. The same tropes and themes appear, but with a more scientific understanding. Or as Vadi puts it:

Measure and Tempo:

And if you heed my doctrines,

You’ll know how to answer with reason

And pluck the rose from the thorns.

To make your opinion clearer,

And to sharpen your intellect,

So you may be able to answer to everyone:

Music adorns her and chooses her as its subject,

Song and sound are added to the art,

To make it a more perfect science.

So Geometry and Music combine

Their scientific virtues in the sword,

To adorn the great light of Mars.

—Vadi (Windsor; Wiktenauer)

There are echoes of Filippo Dardi’s reflection that, “(G)eometry, resembles the skill of fencing because in fencing there is nothing but proper measure.” (Fillippo Dardi (1443); Dean & Stokes Transcription and Translation) As Dardi was himself a doctor of Geometry and Astrology commenting on the art of fencing from a academic perspective, the parallel and sea change from art to science is intriguing. Of course, Vadi is more elegant and thorough than the obscure one-off line we have preserved from Dardi’s letter. It’s worth noting that this notion was later espoused again in the 17th century works of Salvator Fabris, where he says, “We have shunned the use of geometrical terms, although swordsmanship has its foundations more in geometry than in any other science. Simply and as naturally as possible we have tried to bring the art within the capacity of all.” (A.F. Johnson; Wiktenauer).

In music, like fencing, the reintroduction of classical concepts gave birth to a more sophisticated approach to the discussion and theorization of the art. Starting in about the 1420’s the devices of tactus, mensuration, and rhythm were introduced as guidelines to coordinate musical ensembles. Tactus in particular was, “a unit of time indicated by the raising and lowering of the hand” (Hooker, A brief history of tempo)—a concept that’s in no way foreign to the art of fencing.13 Again, this brings our discussion of time back to Aristotle, where time is defined as the motion between two positions of rest or a number of change with respect to the before and after.

Or perhaps one can better surmise this with the words of Johannes Liechtenauer, “This you should grasp: All arts have length and measure.” (Trosclair; Wiktenauer)

Transitioning on the principle of a raised hand dictating tempo, one of the key concepts we’ve seen illustrated in parallel from I.33 to KdF, is the execution of actions preceded by a crossing.

When you wish to enter into half sword

As the companion, lifts his sword

Then don’t hold back

Grab the tempo or it will cost you dear.This is of course Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s third tempo of attack—when they raise their weapon to attack. But leaving the Bolognese authors aside for a moment, let’s draw another parallel between Vadi and the Liechtenauer tradition, to satisfy the objective of this article in a more resolute manner. From the gloss of Sigmund ain Ringeck, “When the opponent comes before such that you must parry them, swiftly work Indes to the nearest opening during the parry, so that you hit them the moment before they accomplish their play.” (Trosclair; Wiktenauer)

From defense to offense, we can add, “just as the swords spark together, whether they have bound soft or hard, and as soon as you have perceived that, think of the word "in-the-moment"; that is, in that same swift perceiving of the soft and of the hard, you shall work to the nearest opening, so [he] becomes struck before he will have his insight.” (Trosclair; Wiktenauer)

Vadi’s words unify the approach (like his predicesor Fiore):

Instruction of the sword:

It is necessary that the sword should be

A great shield that covers all of you,

And grasp this fruit,

That I give you for your instruction.

Be sure that your sword is never far away

In making guards or striking

Oh how sensible this thing is,

That your sword makes short movements.

Make it so your point watches the face

Of the companion, in guard or striking,

You will take away his courage,

Seeing always the point staying in front of him.

And you will make your plays always forwards,

With your sword and with a small turn,

With a serene and relaxed hand,

Often breaking the tempo of the companion,

You will weave a web better than a spider’s.

To which we can add, “This is what you shall quite precisely note when one with a cut or with a thrust or otherwise binds against your sword: whether they are soft or hard upon the sword. And when you have sensed this, you shall know Indes which is the best: whether you rush upon them with the before or with the after. But you shall not allow yourself to be too hasty with your war with your onrush. For the war is nothing other than the windings upon the sword.” (Trosclair; Wiktenauer)

Vadi agrees:

It is necessary that no one contradicts this

Because you will be stronger, and more secure

Hard in defence

And make war with the shortest motion

And neither can anyone make you fall.The point that I’m trying to make here—if it hasn’t become clear—is that the same concepts can be explained with tempo in mind and what acting in tempo seeks to achieve, in a way that enriches the discussion of the medieval authors. Vadi is not Fiore— though he is unequivocally inspired by the Friulian master—nor is his text directly related to the Liechtenauer tradition, and yet we can read the same tropes further outlined with the principles of scientific reasoning buried in his prose.

To this consensus we can add authors like Marozzo and Manciolino at the turn of the 16th century. Marozzo’s Opera Nova lends insight to the earlier discussion of indes with the following: “You should hold it to be a certain factor that no one who is attacked when raising out of a guard, or in falling from a guard, can perform any counter except for an instinctive response as if he knew nothing…But if perchance you were to attack him when he was neither rising nor falling, be advised that he could interrupt your intention with a variety of blows. So if you wish for honor, be attentive, and look to attack him as he rises or falls from his guard with his counters.” (Marozzo, Capitolo 171; Swanger, pg. 256)

Manciolino’s Opera Nova says much the same thing: “Since no blow can be reasonably performed without ending in a guard, the virtue of a fencer is to be found in the raising and lowering of the guards. In consequence of this principle, he who renews his attack before settling in guard will be more apt to win. This is because it is easier to attack an opponent whose action is interrupted.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 112)

One thing that should have become apparent with that jaunt forward in time, is that the approach of these later authors stands apart from the poetic prose of Vadi, and laconic simplicity of the medieval masters, as we see in Marozzo and Manciolino a more rhetorical and vade mecum approach to discussing the art of fencing. Less Virgil and more Cicero, which is unsurprising given the focus on education in Bologna we discussed earlier.

But before we drift too far from Vadi, I want to highlight an excellent article by Jamie MacIver that relates plays and principles in Vadi to Giovanni dall’Agocchie’s five tempos of attack, which you can read here. This is an incredibly important article, and deserves your attention.

Here we have two authors almost a century a part harmonizing on the tempo’s of fencing. For the sake of brevity, I’ll summarize by only highlighting each tempo and corresponding play as they’re outlined in the article. Many thanks to Jamie MacIver for giving me permission to share this.

1st Tempo: When you’ve made a parry.

Vadi, Chapter 3:

Know that skill always defeats natural ability,

Cover and then immediately attack,

And in wide or close [play] you will defeat strength.

(MacIver)2nd Tempo: When their blow goes past.

Vadi, Chapter 8:

Your sword is lost when striking with a cut

If during the strike your point moves off-line

(MacIver)3rd Tempo: When they raise their sword to strike.

Vadi, Chapter 10:

When you wish to enter to middle play

As your partner lifts their sword

Decide not to stay at bay

And seize the tempo so that it does not

cost you dearly

(MacIver)4th Tempo: Injudiciously change guard.

Vadi, Chapter 16:

Beware that your sword never remains

Far away from you, either when in

guard or while striking

(MacIver)

Vadi, Chapter 17:

Often I [the thrust] force the guards to move

When someone throws me to confront them

(MacIver)

Vadi, Chapter 13:

From one side you strike

Your feint goes to the other

And as their parry loses its way

You can hammer to another target

(MacIver)5th Tempo: As they raise their foot.

Vadi, Chapter 3:

And when you have found [the correct measure]

As I say here, do not lose [the tempo]

When you see that they move their sword,

Or they make too large a step

Or you retreat, or they seek to close in

(MacIver)The reason I wanted to use elements of this piece and highlight Jamie’s work is because I think it beautifully illustrates how tempo gives rise to tactics. Tempo is the b variable in equation of fencing, measure is our a, and we’re solving for x, which is simply how to strike our opponent without being struck. We see this wonderfully outlined in Chapter 3 of Vadi, where he says, “And when you have found [the correct measure]; As I say here; do not lose [the tempo]; When you see that they move their sword; Or they make too large a step; Or you retreat; or they seek to close in.” (MacIver) Find the measure and seek the tempo.

There is however a fourth variable that comes into play when we are attacking, and this is where provocations come in handy. Our y variable is the guard our opponent is in, and if you deliver an attack without first solving for y, you’ll inevitably double. So, we have to figure the y with our a and b, before we can solve x, and this is usually done by attacking the opponent to provoke them into a tempo, which Vadi highlights beautifully with the following: “Often I [the thrust] force the guards to move; When someone throws me to confront them,” (MacIver) and, “From one side you strike; Your feint goes to the other; And as their parry loses its way; You can hammer to another target.” (MacIver)

Without digressing any further into tactics, allow me to discuss one last point that will become relevant in a moment, and represents a contentious argument among authors in the 16th and 17th century—mezzo tempo.

Vadi says this of mezzo tempo: “I cannot show you in writing; The theory and way of the half tempo; Because the shortness of the tempo and its strike; Reside in the wrist; The half tempo is just one turn; Of the wrist: quick and immediately striking; It can rarely fail; When it is done in good measure.” (Windsor; Wiktenauer)

The Anonimo both agrees and disagrees with this in the following word salad: “In the art of the sword there is no such thing as a half tempo because all are simply tempi, but because of the half attack, in this art of the sword we have things we call a half tempo. And so the term half attack comes to form the term half tempo, but in the usage of the sword all actions are simply tempi; one may find tempi that must be made with greater quickness, and so it will be necessary to make the blows or cuts with greater speed; but because very often a fighter will want to make an attack at the enemy in the shortest time possible and will stop their sword in a stretta guard, some will call this occurrence a half tempo, by reason of the half attack, but nevertheless it will be a tempo.” (Fratus, pg. 64)

This notion, as convoluted as it seems, sticks with the Anonymous author’s core principle that any movement of the sword is simply a tempo, but also fits with Aristotle's digressions on the characteristics of time and motion.

It also affords us a nice transition into the Bolognese authors.

The Opera Novas of Marozzo and Manciolino

Antonio Manciolino opens his New Work with a number of statements about tempo. Perhaps the best place to start is with a reflection that anyone who has ever picked up a sword can relate, “Fencers who deliver many blows without any measure or tempo may indeed reach the opponent with one of their attacks; but this will not redeem them of their bad form, being the fruit of chance rather than skill. Instead we call gravi & appostati14 those who seek to attack their opponent with tempo and elegance.” (Leoni, pg. 112) Arguably we could categorize this as a commentary on a principle at the heart of what will later become dall’Agocchie's 5th tempo of attack.

Of the early Bolognese masters, Antonio Manciolino was likely the most educated. He discusses Aristotle's quality of opposites when he goes on a tangent about the difference between the art of fencing and dueling law (which may be a subtle jab at Marozzo—who knows?). He also references Aristotle when he defines the qualities of a master, stating, “Nobody can be deemed perfect in this art (as well as in others) unless he can impart his knowledge to others. As the Philosopher said in the Ethics, the mark of the expert is the ability to teach.” (Leoni, pg. 113) I believe Manciolino is referencing Aristotle’s Metaphysics, though he could be paraphrasing a number of passages in Nicomachean Ethics.

And in general it is a sign of the man who knows and of the man who does not know, that the former can teach, and therefore we think art more truly knowledge than experience is; for artists can teach, and men of mere experience cannot.

Aristotle's Metaphysics, Book 1 (W.D. Ross)

So, what else does our wise and principled guide to Renaissance martial arts have to say about tempo? We’re going on a bit of a journey here that extends beyond just tempo, so bear with me. Manciolino’s first quote on tempo is, “The most admirable of all blows is the mandritto, because it is the most virtuous and noble, since it is more dangerous and awkward to perform. Using the mandritto is more dangerous than using the riverso because it causes you to be completely uncovered in that tempo—this is why it is deemed more noble” (Leoni, pg. 110)

Let’s pause here for a second and recognize the general fencing principle that Manciolino is highlighting. Giving up or exposing your outside line (that is, the right side of your body) is always dangerous. Moreover, an exorbitant number of plays and devices we see in the entirety of the historical fencing corpus are aimed at controlling the outside line. It shows up in Liechtenauer; “Therefore orchestrate it that you are the first in all confrontations of fencing and arrive on the right side of someone, where you are robustly surer of everything than the opponent” (3227A; Trosclair, Wiktenauer). As well as in I.33, Fiore, Vadi, and the Bolognese corpus.

I feel like that needed to be expressed so people understood exactly what Manciolino is talking about. When you cut a mandritto, the attack travels from right to left, and exposes the outside line in the tempo of the cut, where a roverso—going left to right—closes the outside line. This is outlined in Viggiani:

(I)ndeed I will also give you this reason, which I had not previously remembered: the rovescio, moreso than the offensive mandritto, offends the enemy in the right side, whereby it aids [59V] and defends one, and for this reason: it comes to pass that the mandritto offends the more mortal and weaker parts; it can be said to be more offensive; tell me, if with a rovescio you sever your enemy’s right arm, then what a defense it would be?

—Viggiani (Swanger; pg. 22)

Moving on we’ll see Manciolino discuss the first of dall’Agocchie's 5 tempos of attack:

It is necessary to develop the knowledge of tempi, without which your fencing will remain imperfect. Therefore, let me advise you that as the opponent’s attack has passed outside your presence, this is the correct tempo in which to follow with the riposte you deem most appropriate.

—Manciolino (Leoni, pg. 111)

This is of course, dall’Agocchie’s 2nd tempo of attack, when their blow goes past. He follows this up by highlighting the 1st tempo—when you've made a defense—with one of my favorite lines in his book.

Just as you should not strike without parrying, you should not parry without striking—always observing the correct tempi. If you were to always parry without striking, you would make your timidity plain to your adversary, unless you were to push the opponent back with your parry, in which case you would show your valor. Correct parries, in fact, are performed going forward and not backward(.)

—Manciolino (Leoni, pg. 111)

To the third tempo of attack, Manciolino outlines two principles, one of provocation, and one rooted in contratempo. The first regarding provocation states the following:

If you are trying to make the opponent deliver an attack in order to strike him within that same tempo, you should yourself deliver the same attack three or four times in a row, almost as an invitation. It is common among fencers to ape one-another, so your opponent will see himself compelled to eventually do the same to you; and in that moment you will perform the attack as planned.

—Manciolino (Leoni, pg. 112)

This is the foundation of the principle of provocation outlined by Giovanni dall'Agocchie some forty years later in his Dell'Arte di Scrima Libri Tre, where he states:

Said provocations, so that you understand better, are performed for two reasons. One is in order to make the enemy depart from his guard and incite him to strike, so that one can attack him more safely (as I’ve said). The other is because from the said provocations arise attacks which one can then perform with greater advantage, because if you proceed to attack determinedly and without judgment when your enemy is fixed in guard, you’ll proceed with significant disadvantage, since he’ll be able to perform [24verso] many counters. Therefore I want to advise you that you mustn’t be the first to attack determinedly for any reason, waiting instead for the tempi. Rather, fix yourself in your guards with subtle discernment, always keeping your eyes on your enemy’s hand more so than on the rest of him.

—dall’Agocchie (Swanger, pg. 27)

This draws us back to the core focus we came to understand in Vadi, where he says, “Often I [the thrust] force the guards to move” and later expounds, “From one side you strike; Your feint goes to the other; And as their parry loses its way; You can hammer to another target.” (Windsor; Wiktenauer)

Similarly, in the Liechtenauer tradition, “Because if you execute the Vorschlag, whether you hit or miss, you then always execute the Nachschlag in one fluid motion, swiftly and quickly so that the opponent cannot come to blows with anything and you shall orchestrate it in such a way that you always preempt the opponent in all situations of fencing.” (Trosclair, Wiktenauer) Though the underlying principle remains the same, there is a pointed difference that needs to be elaborated upon.

There's a subtle variation in the way Manciolino and dall’Agocchie anticipate the response of the opponent, and it's worth taking a moment to outline for the sake of a thorough analysis.

Our Bolognese authors are working off of the principle that the opponent will be as knowledgeable and skilled as they are, that they’ll adhere to the principles that they've already outlined in their text, assuming that when you throw an attack your opponent will act in tempo (dall’Agocchie's 1st; when you've made a parry), and counter attack—Just as you should not strike without parrying, you should not parry without striking—always observing the correct tempi. (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 111)

Now, the same reasoning is outlined in the zettel and glossed by the authors of the KdF tradition, “If you are obligated to not execute the Vorschlag, you always have the Nachschlag available in the sense and in the spirit that you are always in motion and do not either dawdle nor hesitate with anything. Rather, you always conduct one after the other swiftly and quickly, so that the opponent cannot possibly come to anything.” (3227a; Trosclair, Wiktenauer)

Which makes the following so much more impactful, “just as the swords spark together, whether they have bound soft or hard, and as soon as you have perceived that, think of the word "in-the-moment"; that is, in that same swift perceiving of the soft and of the hard, you shall work to the nearest opening, so [he] becomes struck before he will have his insight.” (3227a; Trosclair, Wiktenauer)

Not to be too disparaging here, but the general lack of exploring these principles leads to a style of fencing that we see a lot in competitive HEMA tournaments, and it's perhaps on account of a misconception. I say that because we have an observation from Angelo Viggiani, where he states, “CON: When I think over that which you have said to me just now, I find a clear example in the Germans, who, coming to an armed brawl, deliver a blow per man, and delivering the blow, stop in guard in order to wait for their companion to deliver his, and withhold theirs, and then redouble; behold the two rests with a motion in the middle.” (Viggiani; Swanger, pg. 28)

This of course is coming from Viggiani’s muse Conte d’Agomonte, the Count Egmont, whose authoritatively relating something he hypothetically would have observed as a courtier in the retinue of Charles V, where he was a peer of Albrecht Dürer. Though this observation is likely ascertained from Viggiani’s personal experience with the court fencing masters of the Holy Roman Emperor, given his position and dedication, and related through the authority of his muse.

Which leads us directly to our next quote pertaining to dall’Agocchie’s 3rd tempo of attack, highlighted by Antonio Manciolino, where he provides us with insight, on how to deal with an opponent who understands the outlined principles, echoes Viggiani’s observation, and flushes out our inclusion of the 3227a text above.

If you and your opponent are of equal knowledge of the Art and neither can safely deliver an attack to the other, I advise that you take a chance in your hope for victory. You can either rely on your reflexes and attack in the same tempo as your opponent, or you can strike him wherever you can and immediately spring against him and put your arms around him. By doing this, everyone will judge you the victor.

—Manciolino (Leoni, pg. 112)

When it becomes clear that your opponent is skilled in and well versed in the principles of the 1st tempo, making basic provocations more difficult to execute, whereunto their ability to respond with a treat means that simply creating openings to make their parry lose its way no longer bears its tactical acumen, then striking indes, or in contratempo, becomes paramount. We turn to the third tempo. Here, one can view the five hews in their ultimate glory. Add the Krumphau for good measure, and we can see the art and execution of the KdF tradition aligned in harmony with the contemporary and later Italian authors.

While there are preclusions to a unanimous consent on a unified tactical delineation, the precept of tempo, and how to find those advantages indes or in tempo are ubiquitous.

First concepts are real things that are first grasped by the intellect, like parrying and wounding, and these function in first intention. Second concepts are formed by the intellect, and they produce our second intention, knowledge, in order to be capable of wounding and parrying. These are produced by means of the first, for as soon as our intellect has learned this aim of wounding and parrying, it immediately reasons out how it can be done in different manners and with different methods.

—Giganti (Vansteenkiste; Wiktenauer)

Like Vadi pointed out, there is a third tactical device that can ensure our fencing is both gravi & appostati, and that is mezzo tempo. Paraphrasing the general tactical advice of all the fencing masters once again, as the distance between you and your opponent narrows, so too should the tempo of your actions. Whether you're transitioning from the Zufechten to the Krieg, Gioco Largo to Gioco Stretto, or any of the variations we’ve seen, movements of the sword are proportional to distance.

Rationalizing in this way takes the Anonymous author’s word salad above and gives it some semblance of balance. Any movement of the sword is a tempo, but smaller tempos—mezzo tempos—are usually executed by performing half cuts or tramazzone (cuts with the wrist; a la Vadi), and take half the time, but are still simply tempi. As to be expected, this is clearly outlined in Manciolino’s Opera Nova:

If you are near your opponent, you should never swing a full blow, because your sword should never get out of presence for your own safety. The delivery of these half-blows is called mezzo tempo.

—Manciolino (Leoni, pg. 112)

From Manciolino we’ll turn to Marozzo, who speaks of time regularly. He uses the word tempo 192 times in his Opera Nova, but the discussion of tempo in Marozzo is predominantly related to the movement of the sword in conjunction with the body. This minutia of detail is interesting, and gives the reader a clear sense of body mechanics, but it's a topic for another time. Since I've already used one of Marozzo’s better quotes pertaining to tempo above, I'm going to focus in on one other passage before we transition into Viggiani, and bring this discussion to its natural conclusion.

Cap 35. Which deals with what can be done when true edge to true edge, as well as when false edge to false edge.

When you’re at the true edge, or the false edge, there are many prese of the sword that you can do, and many feints, and turns of the pommel, as you know. You can feint riversi but throw mandritti, or feint mandritti but throw riversi, and even feint riversi and throw riversi, and more kinds, and also you can feint riversi but throw falsi. Given all this, it should come as no surprise that when you come to the aforesaid two modes of the half-sword there are a great number of things that can be done. Yet I tell you that there are few people who display clarity when they’re at the half-sword, whereas those who understand and know how to enter into and exit from those two modes of the half-sword are excellent and perfect fencers, who are familiar with tempi; whereas those who don’t know how to perform the aforesaid art can’t recognize tempi, nor mezzi tempi, so they cannot be perfect fencers. God may will that when they fence against other fencers they sometimes make a touch on them, but they don’t make the touch through their knowledge, but rather through luck, and this is because they are not well-founded in the art of the half-sword.

—Achille Marozzo (Swanger; pg. 111)

This statement echoes Manciolino’s gravi & appostati quote but frames it in terms of the art of fencing from the mezza spada and with pressa. Manciolino lays out a similar sentiment in his mezza spada, stating, “This type of play is first among all others. He who does not understand it perfectly and does not have an excellent foundation in it will never be a good Master. No matter how good a fencer, how skilled in the defense and how quick with his hands, he will be unable to teach the true art to others, since the true art consists in being strongest and most resilient. Rather than knowledgeable, these fencers should more aptly be considered to be lucky when they score a hit.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 153)

There's a theme brewing here, that artful, skillful fencing is done from the crossing of the swords. The means by which you get there is varied, but when the edges bite, or the blades spark—that's where the magic happens. It doesn't matter if you're reading I.33, Fiore, Döbringer and the Geselschaft Liechtenauers, Vadi, or Marozzo and Manciolino, we have a few hundred years of sword fighting history in lockstep on the notion that art of fencing lies in the ability of a practitioner to read and react with cunning and speed from crossing of the swords.

Pleasantly, Marozzo provides some insight as to how he perceives the tempi are used. “Yet I tell you that there are few people who display clarity when they’re at the half-sword, whereas those who understand and know how to enter into and exit from those two modes of the half-sword are excellent and perfect fencers, who are familiar with tempi; whereas those who don’t know how to perform the aforesaid art can’t recognize tempi, nor mezzi tempi, so they cannot be perfect fencers.” (Marozzo; Swanger, pg. 111) Tempi and mezzatempo actions are used to enter and exit the crossings safely. They’re a means to the end of artful fencing.

I think it’s important to examine the tempos of attack again with some of the fresh insights we’ve gained. We’re going to return to Giganti’s more elaborate explanation of tempo, correlate his definitions with dall’Agocchie, and see how this fits into the larger tactical picture that necessitates tempo.

Tempo is recognized in this way: If the enemy is in guard, one needs to position oneself outside of measure and advance with one’s guard, securing oneself from the enemy’s sword with one’s own, and put one’s mind on what he wishes to do.

If he disengages, in the disengagement he can be wounded, and this is a tempo. If he changes guard, while he changes is a tempo. If he turns, it is a tempo. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before he arrives at measure is a tempo to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in one tempo is also a tempo. If the enemy stands still in guard in order to wait and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are at measure, it is a tempo. This is because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita, such as changing guard, is a tempo in the way that all these things are tempi—because they contain different intervals. While the enemy makes one of these motions, he will certainly be wounded because while one moves one cannot wound. It is necessary to learn this in order to be able to wound and parry.

—Nicoletto Giganti (Vansteenkiste; Wiktenauer)

For perspective, here are Giganti’s Tempo’s (italics) outlined above headed by dall’Agocchie’s tempos of attack (bold).

When you have made a parry: If he throws, parrying and wounding in one tempo is also a tempo.

When their blow goes past.

When they raise their weapon to attack: If he disengages, in the disengagement he can be wounded, and this is a tempo.

When they injudiciously change guard: If he changes guard, while he changes is a tempo.

When they take a step: If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before he arrives at measure is a tempo to wound him.

What these tempos do is take the initiative, seize the vor by acting indes, they put the opponent in obedience, or to go back to our chess relation; gain tempi. Once a fencer has tempo, they proceed to attack with impunity. When a fencer is out of tempo, they have to seek the tempos of attack to reclaim tempo, so they can strike their opponent safely. If that sounds like our earlier discussion of vor, nach; strech, schwech, indes, that’s because it is.

If there is one common consensus around anything in fencing, it’s the objective: strike your opponent without being struck. Understanding tempo, from perspectives of both initiative and movement will go a long way to making anyone a better fencer. It will give their art gravi & appostati.

Angelo Viggiani dal Montone

Angelo Viggiani was a mid-16th century fencing master born in Bologna around 1516. His family were of the patrician class of Bolognese nobility, and were longtime members of the Bentivogleschi faction (dating back to the 14th century), which forms the nexus of the Bolognese fencing tradition from Dardi to dall’Agocchie. Perhaps the most famous Viggiani was the great knight, diplomat and doctor of law Melchiore Viggiani, who was active in the mid 15th century, under the Sigoria of Annibale I Bentivoglio. The skillful practice of the art of arms wasn’t unique to the unparalleled prowess of Melchiore however; in the wake of the great scion’s death, both Spezza and Nanne Viggiani showed a tremendous aptitude for the art in the recorded events of their lives.

The Viggiani (Vizzani/Vizani) family were classically a part of the Ghibelline faction, as denoted by the three fleur de lies on the banner across the top of their ancestral arms. This is a theme inherent throughout books one and two of Angelo Viggiani’s work. In the wake of the family’s split from the Bentivogleschi faction in the late 15th century they seemingly returned to their roots, with Carlo Viggiani serving as a decorated captain in the Emperors service during the Italian Wars, and as such Angelo has a tendency single out families native to Bologna based on their loyalties abroad, identifying them as either Guelf or Ghibelline.

From a fencing perspective, Viggiani’s text lo Schermo provides some fascinating insight because he describes the system of fencing native to Bologna for a German audience (the court of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V), and as such we get unprecedented look into some of the floor knowledge and colloquial terminology inherent in the Bolognese tradition.

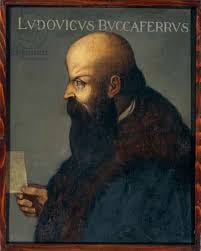

Viggiani starts his third book with a discussion of the three advantages, and builds the conversation into a philosophical explanation of tempo, which is given by his muse Ludovico Boccadiferro, one of the star students of the famous Bolognese Philosopher, and a loyal adherent of the Bentivogleschi faction, Alessandro Achillini.

The advantages are essentially tempos of attack, and they are fueled by the tempos rendered from a prospective opponent. They are:

Advantage of settling yourself in guard

Advantage of the strike

Advantage of the stepping

Settling yourself in guard:

Accordingly it may be said that you settle yourself in guard with advantage when the point of your enemy’s sword is outside your body and not aimed at you, and when the point of your sword is aimed at the body of your enemy in order to offend him, so that you may, in such fashion, easily offend him, and it will be difficult for him to defend himself from you; consequently you will be able to strike him in little time, and in order to defend himself, he will require more time; and conversely, he will find it difficult to offend you, and you will be able to easily [61R] defend yourself from him for the selfsame reason, he having need of much, and you of little time.

—Viggiani (Swanger; pg. 24)

This is the realm where everything we’ve learned of tempo, crossings, before, after, strong, weak, within, and Aristotle are going to converge. Returning to the concept of tempi in chess, we can understand this passage in the following manner: If I set myself in guard with my point on-line, I will easily be able to act in the time of my opponents approach with an attack. This will force them to defend, rendering a tempo, whereby I will gain tempo (vorshlag, gain initiative; obtain the vor). If my opponent were to be the first to attack, because I am settled in guard, I can quickly defend and counter attack (versetz) forcing another tempo out of them, whereby I will gain a tempo (nachshlag, gain initiative; obtain the vor), or force a crossing. This is facilitated by time. Simply put, if the tempo of my action is smaller than my opponents, and done with the proper structure, I will gain tempo.

From a tactical perspective, the role of the attacker, when forced to uncover an opponent fixed in guard is best outlined by the Anonimo Bolognese, where the author says, “Also, you must know that if you find your enemy in a wide guard, then you will use your art to bring his sword into presence. If he has his sword in presence, then you must, by means of feinting, make him put his sword into a wide guard that allows you to control the line, such that his sword will point away from your person and off to the side of your body, and so you will then be able to perform whatever action you wish.” (Anonimo Bolognse; Fratus, pg 75)

The objective of this principle is to gain tempo; from an attacker’s perspective, this can only be achieved by forcing the fencer fixed in guard to render a tempo (i.e., to move), which is typically achieved by feinting. Meanwhile, the defender must act in the movement of the attacker, and pick the correct tempo to unleash their attack. If both fencers are wrong—they will double. This is the fundamental lesson of advantages. You could reasonably read this as, how to act in tempo or gain tempo rather than the advantages (which applies to our 5 tempos of attack). Here, Viggiani gives the nod of advantage to the fencer who is still fixed in guard, due to the copious tempi that are likely to come from a fencer feinting and moving to try to get their counterpart to move themselves. This is because, as Giganti outlined—way back in the opening of this article—“In every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita {person}, such as changing guard, is a tempo in the way that all these things are tempi—because they contain different intervals.”

This is also the crux of our next two advantages.

Advantage of the Strike

ROD: If you always want to attempt to throw blows when you still cannot reach your enemy without more steps, then you will spend too much time in throwing them, and give too much of it to the enemy in order to be able to shun your blow, and [61V] simultaneously to strike you, because you would overly disconcert yourself needing to move yourself from that distance between you. But when you can close with a step, and with half of one, you will not disconcert yourself, and you will strike quickly, without giving the enemy time to protect himself. Then you will have to pay attention that when you strike, you do not look to the point of your own sword, but rather to that of your enemy.

Viggiani (Swanger; pg. 25)

This is on its surface a statement on measure—our a variable listed above in our discussion on provocation. The advantage in striking is when you can deliver your attack by taking the shortest step, a half step. However, Viggiani goes on to clarify:

Therefore, Conte, from your perspective you have the advantage in the strike when you can hit in one step, or half of one; and from the perspective of your enemy, when he would try some blow without being able to reach you, or being able to reach you in more steps, because he, in disconcertedly attempting his blow, or in the elevation of his sword, will give to you time in which to strike him, and similarly, when he, not having regarded the point of your sword, will give to you occasion to offend him.

—Viggiani (Swanger, pg. 25)

Returning to the precept of the advantage of being in guard, if we were to wait for our opponent to approach with feints and provocations, as the anonymous author encourages, we will be able to find tempo to attack in one of the following ways: when they throw a blow while stepping or when they raise their sword to attack. This highlights three tempos of attack: when they take a step, when their blow goes past and when they raise their weapon to attack.

When they take a step: when he would try some blow without being able to reach you.

When their blow goes past: because he, in disconcertedly attempting his blow.

When they raise their weapon to attack: or in the elevation of his sword.

For the sake of completeness, the advantage of settling yourself in guard renders the following:

When you’ve made a defense: you will be able to easily [61R] defend yourself from him for the selfsame reason, he having need of much, and you of little time.

Angelo Viggiani precedes this argument with a discussion on provocation in his terms, echoing the sentiment of the Anonymous author, and highlighting our fifth tempo of attack:

CON: This (I believe) one could quite well do, if the enemy were not intent upon this exercise. But if he shrewdly did not allow me to place myself in guard with advantage, what would I have to do?

ROD: I would like you to step, vaulting at him diagonally, and wearying him continuously, now with a mezo mandritto, and now with a mezo rovescio, and often with a variety of feints, taking heed nonetheless always to keep your body away from the point of his sword, because he could easily give you the time and the occasion to seize the advantage of placing yourself in guard.

—Viggiani (Swanger, pg. 24

The objective being, to get your opponent’s sword moving, so you can find occasion to settle in guard, and act in tempo, or initiate a counter attack in the tempo of their movement; facilitated by mezo {mezzo} tempo actions. Sound familiar?

Injudicious guard change: wearying him continuously…because he could easily give you the time and the occasion to seize the advantage of placing yourself in guard.

Advantage of Stepping:

ROD: Briefly I tell you that when the enemy, in stepping, lifts his left foot in order to move a step, that he is then a bit discommoded, and then you can strike him with ease, and again change guard without fear, because he is intent on the other; and this is from the perspective of the enemy. From your perspective, then, when you are stepping, approaching the enemy, and go closing the step, then you have much advantage; for as much closer as you are with your feet, you will have that much more force in your blows, and in your self defense, and otherwise accordingly will you be able to close with your enemy in less time.

—Viggiani (Swanger, pg. 25)

Moving the feet can compromise the structure and integrity of a guard, rendering advantage to the opponent. Catching the opponent in the tempo of that movement, is greatly to your advantage. Viggiani tries to mitigate the disadvantage by encouraging gathering steps when entering measure (i.e., the distance of being able to strike with a step, or a half step).

This all comes together in Viggiani’s summation of the advantages, where he states:

One never strikes safely if not during the disadvantage of the enemy; therefore it seems impossible to say that both may have the advantage, and be in equal conditions. Indeed because you ask not of throwing a blow, but of going to encounter the enemy, I would say that it is better to wait; because he who would go discommodes himself, and [62V] the moving of his body often moves the spirit as well; and who stands firm does not receive discommodity, neither by change of body nor of spirit; hence it appears that when both the one and the other could have advantage, that the lesser advantage would always be to whom would go to encounter his enemy; and that when the both could be of disadvantage, the lesser disadvantage would always be to that one who waits for the adversary, and so much more so if he who waits knows to maintain himself in guard.

—Viggiani (Swanger, pg. 26)

To be in advantage, one must limit the tempos that they are rendering to their opponent. Returning to our Giganti quote, “In every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita {person}, such as changing guard, is a tempo in the way that all these things are tempi—because they contain different intervals.” Those intervals, are a, “a number of change with respect to the before and after.” Indes. Guard, motion, guard. The prerogative of a fencer is to act in tempo to gain tempo. This is not a concept foreign to antiquarian authors, nor their later counterparts. When Liechtenauer says:

Precisely note this

Cuts, thrusts, position, soft or hard

31 Indes and Before, After

Without rush, your war is not hasty.

32 For the one whose war takes aim

Above, they will be shamed below.

33 In all winds

Cut, stab, slice learn to find

34 Also with that you shall

Gauge cut, stab or slice

35 In all encounters

Of the masters, if you wish to dishonor them.

ⅺ Do not cut to the sword,

Rather, keep watch for the openings

ⅹⅵ Of the head, of the body

If you wish to remain without harm

ⅹⅶ You hit or miss

Considering as follows so that you target the openings

ⅹⅷ In every lesson,

Turn the point toward the openings.

ⅹⅸ Whoever cuts around widely,

They will often be shamed severely.

ⅹⅹ In the most direct way possible,

Deliver sudden cuts, stabs wisely.[85]

ⅹⅺ And one shall also always step

To their right side

ⅹⅻ So that you can begin

Fencing or wrestling with advantage.

—3227a (Trosclair; Wiktenauer)The idea of not rushing the war is, in my opinion, important to note here. While the Gesellshaft Liechtenauer authors are not always consistent about the conduct of the zufechten, the idea that one needs to strike first to claim the vor does not preclude the idea of acting in tempo. To the contrary, as we’ve seen from Vadi to Viggiani, I.33 to Liechtenauer, to wisely seek the openings one needs to act in tempo, this could be indes of the opponent’s approach or a guard change, or in the time of their attack. Regardless, in order to attack safely, one must proceed with advantage, or they risk being struck or stuck in a weak position, and every consideration, when attacking, provoking or defending must gain tempo by acting in tempo. To outline this, Viggiani turns to his muse Ludovico Bocadiferro.

Tempo According to the Philosopher:

CON: I rest very satisfied by such as you have said to me concerning wherein may lie the advantage in placing oneself in guard while striking and stepping; now I wish to know what tempo is, and what is signified to us by saying a “tempo” and a “mezo tempo”.

ROD: It is a great controversy among the philosophers, in viewing the nature of tempo, and it is difficult to comprehend, and better to inquire about it of Bocadiferro, now that we come to it.

CON: O Dottore, what do you understand about tempo, and what it is?

BOC: It will be difficult to understand it, Signor Conte; the philosophers say that tempo is measured in motion, and in rest, according to earlier and later; and more intelligently, I say to you, that a body which moves itself, moves itself from one place in order to travel to another; the place from whence it departs is one end of that journey, and the motion is the other end; now divide that journey and that path into two equal parts through the middle; the first half toward the end from whence it departs is called the first part; the other half is called the final part; this consideration of the first and second part (that is to say, earlier and later) in the discourse of our spirit, the philosophers call “tempo”, where the numbering of the parts of the successive motion is tempo.

To which he later continues: