Introduction:

There is perhaps no one more essential to the foundation of the Bentivoglio Signoria in Bologna than Ser Cola d’Ascoli. Like all good agents of espionage, keepers of secrets, or knowers of things, his life is rather a mystery—but he has a knack for showing up when it matters the most. Let's get to know him better.

A series of letters to Angelo da Bari in Pisa, dated between 1415-1420, on behalf of the Acciaioli laborers, indicates that he may have been active politically in his home of Ascoli prior to meeting and taking employment with Antonio Bentivoglio sometime that decade.1 In the funerary note recorded by Cherubino Ghirardacci in his Della historia di Bologna, he provides some pertinent biographical details:

(1477) Cola da Ascoli, a man of learning and experience in the affairs of the republic, died. He was formerly secretary to Antonio Galeazzo, Annibale Bentivoglio, and Giovanni Bentivoglio, from whom he received the arms of the house of Bentivoglio. While he lived, he built a chapel in San Jacopo near the sacristy, where the Most Holy Sacrament stood. Today, with the Bentivoglio family's permission, it is dedicated to San Michele Arcangelo. There is a beautiful altarpiece by Lorenzo da Bologna, a famous painter who succeeded Michelangelo in San Pietro in Rome. It is one of the most beautiful things in Bologna. Cola was buried on May 13, a Tuesday, in the church of San Jacopo with great honor. (pg. 216)

Ser Cola is often referred to as a Secretario, or Cancellieri. In an official capacity this meant an advisor for the council of sixteen reformers, or the Sedici Reformati, and while Ser Cola did hold that position on behalf of the republic for a spell between 1445-1455—after the death of Annibale Bentivoglio—his primary responsibilities were often carried out in a similar capacity on behalf of the Bentivoglio family, rather than the state.

Because Ser Cola’s timeline is going to jump around a bit, it’s helpful to view a timeline of when certain members of the Bentivoglio family were in power:

Giovanni Bentivoglio: 1400-1402

Antonio Bentivoglio: 1416-1421

Annibale Bentivoglio: 1443-1445

Santi Bentivoglio: 1446-1463

Giovanni II Bentivoglio: 1463-1506

Similarly, I tend to use a bit of historical jargon, so here are some helpful tips and terms that will make the story more enjoyable:

—eschi: The suffix ‘eschi’ usually denotes a family faction, or a group loyal to a specific lord. For example, the Bentivogleschi were a group of families in Bologna loyal to the Bentivoglio.

Regimento: The collective government of Bologna.

Anziani: The Bolognese Congressional body

Sedici: The Bolognese Senatorial body

Podestà: Governor, but more like the District Attorney

Legate: The Papal Governor of the City

At the Behest of Antonio Bentivoglio:

Ser Cola first appears in the Bolognese Chronicles in 1435. Bologna was in a period of transition, the brief Canetoli Signoria (1430-1434) had come to an end thanks to concerted efforts of Antonio Bentivoglio and the Papal Gonfaloniere Iacopo Caldora, along with a consortium of citizens hell-bent of throwing off the yoke of the violent Canetoli regime. The new Papal Legate; Daniele da Treviso, the bishop of Concordia, made it his mission to restore order and curb the perpetual feuding that had plagued the city since its bid for independence in 1416. To do this, he assigned Baldassare Offida—a condottiere of questionable integrity2—as his Podestà.3 Offida came to Bologna accompanied by his regiment of 200 loyal soldiers and started creating problems almost immediately.4

Offida’s first act as Podesta was to fire all of the infantrymen and cavalrymen employed in the service of the city of Bologna so he could replace them with his loyal cadre of soldiers. The now curtailed nobleman Battista Canetoli was charged with executing this directive, but instead of following through on the Podestà’s request, he tried to entice the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti to send his chief condottiere, Niccolo Piccinino, to come to Bologna to liberate the city from Papal control.5

This didn’t work out the way he’d hoped.

Offida found out about the plot and was planning to have Battista arrested, but was quickly advised to take a different course due to the bloodshed and violence that would follow such an affront. Instead, he watched and waited for Canetoli to make his move, and secretly negotiated with Piccinino’s rival, Francesco Sforza, to send Bologna aid. Before the Duke of Milan could act on the impetus of Canetoli, 600 Sforsechi soldiers rode through the San Mamolo gate under the command of Sigismondo Malatesta, and Battista Canetoli fled for Correggio disguised as a huntsman, with the rest of his family and Caneschi allies not far behind.6

In the wake of this kerfuffle, Offida tightened security in the city by placing his troops in command of the gates and fortresses and made sure that the new batch of city officials elected into the Regimento were sympathetic to the whims of His Beatitudes, Eugenus IV.7 Bologna was on a knife’s edge: Offida had chosen the stick in lieu of the carrot, and the Bolognese people weren’t keen on taking a beating without some form of recourse.

This was the contentious environment that Antonio Bentivoglio inherited when he returned to Bologna after a 15-year and 3-month-long exile from the city.8 His Holiness, Eugenus IV, was in Antonio’s debt and granted his request to return despite the protestations of Daniele da Treviso and Baldassare Offida. Ghirardacci records his triumphal return home like this:

On Sunday, December 4th, at 10 p.m., {Antonio} entered Bologna and immediately went to visit the governor, then went home to rest. When he entered Bologna, his friends gathered in such numbers that the house could not contain them all(.) He was so beloved by the citizens that they {had} quickly furnished his house with everything he needed; besides which he was visited and presented to by the people every day. When he went out in public in the city, he was followed by an infinite throng of people; and this great love and affection of his friends and the people harmed him greatly, because the governor, who was zealous for the city, took note of everything.

It wasn’t only the Legate and his administrators that Antonio needed to watch out for.

The flight of the Caneschi and the triumphant return of Antonio Bentivoglio was a double gut punch for the adherents of the Maltraversi9 faction in Bologna, who’d recently thrown their hat in the ring with Battista Canetoli. Domenico and Giovanni Isolani, Giovanni di Lignano, and Giovanni del Testa Gozzadini, four key Maltraversi adherents, sought an audience with Baldassare Offida, and poured poisoned suspicions in his ears, arguing, “If {you} wish to preserve the city in the devotion of the Holy Mother Church, then it is necessary to put a brake on the greatness of Antonio {Bentivoglio}, who seems to want to make himself lord of Bologna like his father Giovanni, which is an easy thing for him—having the hearts of the people in his hands” (Ghirardacci; pg. 45).10

Offida certainly heeded their warning and called a number of his soldiers to Palazzo Re Enzo for a ‘review’. This drastic measure alerted Ser Cola that something was afoot. After some quick sleuthing, he uncovered the developing plot and warned Antonio that the Podestà was going to have him killed. In light of this, Antonio made it a point to tell the people who gathered outside his door—daily—to stop following him around, on account that it was raising unnecessary suspicion. Alas, on the 23rd of December, Antonio was summoned to have an audience with Offida.11

He started his trek to the Basilica of San Petronio in the company of Ser Cola, Giovanni Fantuzzi, and Gasparo Malvezzi—his most trusted friends and advisors. When they reached Asinelli tower, he turned to his companions and asked them to go home, noting that if he were to die at the hands of Offida, it would be better if they were alive to enact his revenge.12

Antonio attended mass, confessed his sins, and then went to see the Podestà, who—he discovered—had also summoned his close friend and faction ally Tomaso Zambeccari. Upon Antonio’s arrival at Palazzo Re Enzo, Offida took him by the hand—all smiles, jokes, and jovial platitudes—and led him into private council. When they were done, Antonio asked Baldassare if the soldiers in the square were summoned to arrest him, and the Podestà shrugged this off with a laugh and some reassuring words, and repeated the exercise with Zambeccari.13

As Antonio’s foot left the last landing of the rickety old wooden staircase into the Piazza of the Palazzo, he was surrounded by 25 soldiers, who informed him he was under arrest by the order of the Podestà.14 In response to this, Antonio snapped, “And what have I done? Is this perhaps the reward for my merits that the Church offers me for such loyalty and the servitude that I have demonstrated to her?” (Ghirardacci, pg. 45).

To which the soldiers forced a gag in his mouth, pushed him to his knees, and unceremoniously cut his head off without giving him time for a final confession. Meanwhile, upstairs in the palazzo, Offida had taken a rope and wrapped it around Zambeccari’s throat, threaded it through the rafters, and kicked him out over the staircase to hang. Afterwards, their bodies were buried in an unmarked grave, with no headstone, to avoid any suspicion, and give time for Offida to prepare to pacify the city.15

In the wake of this coup de force, the Podestà had his men collect the weapons and armor from the houses of the Bentivogleschi and Caneschi. Then, to ensure the true nature of his plot remained sufficiently covered, he arrested Ser Cola d’Ascoli, and condemned him to death.16

On Christmas Eve, Ser Cola was led to the executioner’s block, where the charges were read. He was accused of conspiring with Antonio Bentivoglio and Tomaso Zambeccari to invite Filippo Maria Visconti to take dominion of the city of Bologna. The executioner had just drawn the final hone across the blade of his axe as the Marshall issued the sentence, when suddenly the procession was interrupted by a courier in Papal livery. He bore a letter from His Holiness Pope Eugenus IV, demanding the pardon of Ser Cola d’Ascoli.17

According to Ghirardacci, the document was a ruse, a forgery composed by Offida so he could make his brutal execution of Bentivoglio and Zambeccari seem like it was the will of the Pope and publicly discredit Ser Cola d’Ascoli.

He made a crucial mistake.

Later that year, in late August, Francesco Sforza abandoned his Condotta {contract} with the Holy Mother Church while his army was campaigning in the Romagna (southeast of Bologna) near the Polledrano Bridge. Baldassare Offida and Daniele da Treviso were afraid he would turn his covetous eye toward Bologna, and so resolved to take him out before he could besiege the city.18

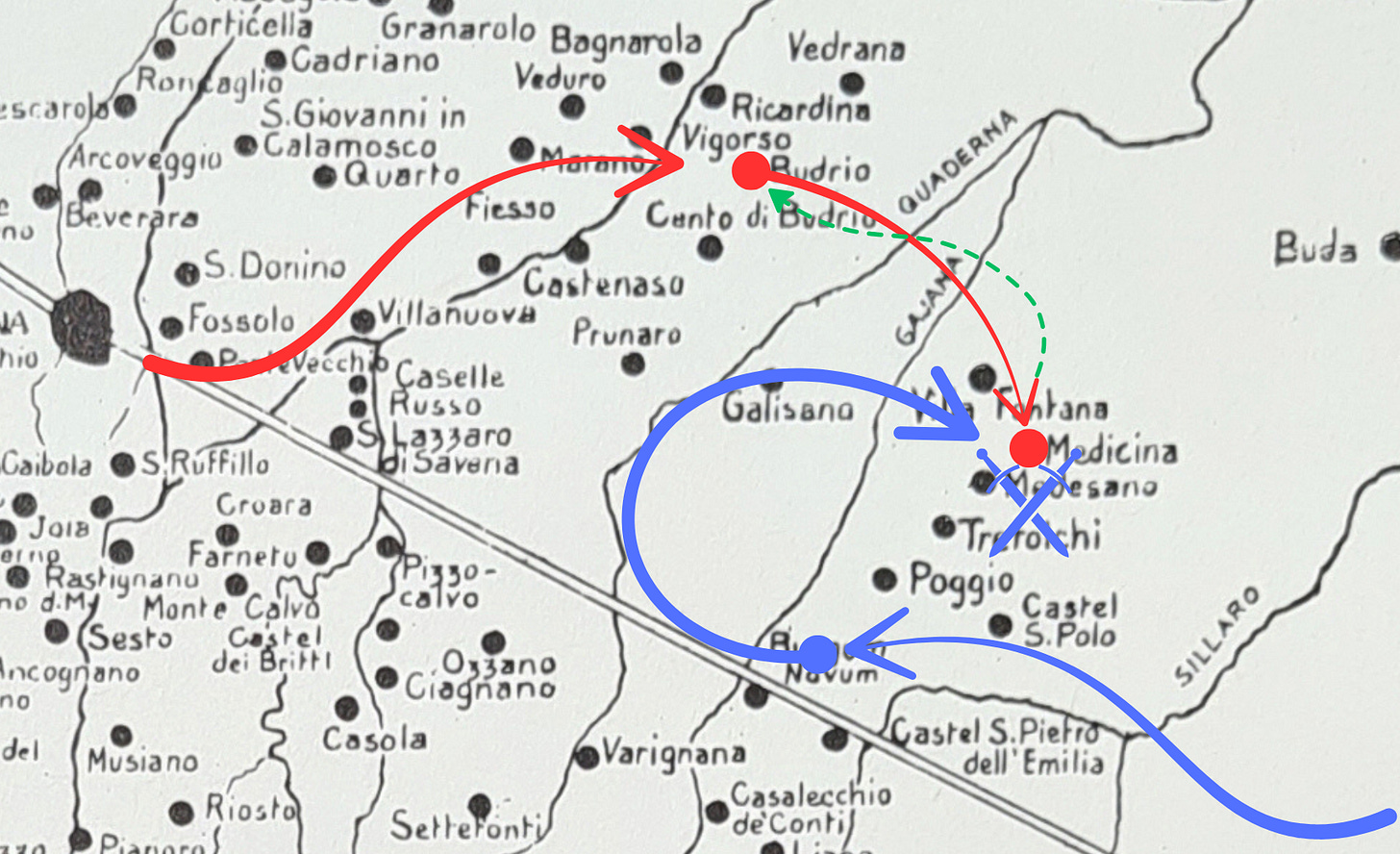

Offida and the Papal Gonfaloniere, Pietro Giovanni Paolo, rode out of Bologna with his Holiness’ army at a breakneck speed by way of Budrio to set an ambush for Sforza’s forces in Medecina. On the 9th of September, they dismounted their men-at-arms and took position, but Francesco’s army never showed—they were tipped-off.19 Instead, Francesco’s forces had taken a more southerly route through Canalovo in Imola and threatened to flank Offida’s forces in Medecina. On account of this, Offida and Giovanni Paolo pulled their forces back behind the Reccardina bridge, settling into position on the 15th. Hearing of this, Sforza feigned a retreat back into the Romagna by sending his entire baggage train back to his county in Cortignola, and dispatched a knight of some repute to inform the Papal captains that this was his intent, along with an offer of his service’s if the terms were good enough.20

This was just enough to get Offida and Giovanni Paolo to drop their guard. On the 16th, Sforza’s company armed and mounted, stormed through Riccardina and routed the Papal forces. All of His Holiness’ captains of repute were captured or killed including Pietro Giovanni Paolo—but somehow, Offida managed to escape and locked himself in the fortress of nearby Budrio.21 Sforza was not a man to take insults or ambushes lightly, and surrounded the fortress demanding that if the garrison didn’t give him Baldassare Offida, he would put them all to the sword. The people of Budrio gladly surrendered the Bolognese Podestà.22

Now, this is where the story gets really interesting. Sforza sent Offida to Cortignola, where he interrogated and tortured him, then handed him off to his captain Ghierono di Fermo della Marca, who delivered the beleaguered Offida to Girolamo dalla Seda, aka the Count.23

Giolamo dalla Seda was a ‘servant’ of Antonio Bentivoglio. Once he’d bound Offida’s hands he said to him, “Here you are, traitor, who wrongly killed Antonio, my dear lord; if it were right for me now, with these hands I would take your heart out of your chest and feed it to the dogs.”24

To which Offida cowered, “This must not immediately be attributed to me, but also to the Maltraversi.”25

The Count was unmoved. He buried Offida neck deep in the ground somewhere near Ghierono, and gave him just enough sustenance to prevent him from dying prematurely—he wanted to see the flesh of his face eaten by ants, spiders, beetles, and worms while his body rotted beneath the earth.26 Ghirardacci records Offida’s demise like this:

Girolamo therefore led him to Ghierono, where he was stripped naked, wrapped in a freshly skinned ox hide, and then buried in the ground with only his head remaining above the surface. He was given food in measured quantities for many days, which he ate with infinite anguish, until finally, cruel as he was, he died a horrible death. He had already been hanged for his crimes, but someone cut the rope and saved his life.

{Offida} was a malicious, proud, and ambitious man. He kept his rooms furnished with the finest fabrics and the floor was completely covered with cloth. When he gave audience, he wanted men to speak to him on their knees until he motioned for them to stand up. When he rode in public, he had a horse laden with ropes led behind him to frighten the people, and when he spoke, he always threatened them with a most cruel death, so that everyone trembled at his deeds.

Brutal. The contrast between Antonio’s execution, being beheaded and then buried in an unmarked grave, and Offida’s execution, being buried alive with his head above the ground, is poetic.

We can call this ‘reading between the lines’, or purely based speculation, but Offida’s fate was sealed the moment he let Ser Cola d’Ascoli live as a matter of political expediency. Obviously, Ser Cola is not specifically implicated in tipping off Francesco Sforza, but let’s look at this as a whole, and use Occam's Razor—shall we?

Ser Cola is humiliated, but pardoned.

Months later, Francesco Sforza is tipped off about an ambush by Papal forces, leaving Bologna.

When Offida is inevitably captured, he’s handed over to an agent of the Bentivoglio and thoughtfully executed.

Chronologically, it’s hard to state how influential—how powerful Ser Cola really was, so just keep this one in your memory bank, and we’ll come back to it after we have a bit more perspective. He’s one of those people who, when you realize what he was capable of, you start to see his shadow everywhere. We’re not chasing shadows, though, we’re only touching the points in history when he’s specifically named, so let’s get into our second story!

At the Behest of the Bentivogleschi:

After the death of Offida, the Bentivogleschi made a deal with Filippo Maria Visconti and Niccolo Piccinino to seize control of the city, and co-rule. It didn't quite work out how they’d hoped…

Long story short—Antonio’s son, Annibale Bentivoglio came back to the city after the Bentivogleschi and Piccinino successfully pulled off the coup. Piccinino was cool with this, but eventually started to freak out about how beloved Annibale was and had him arrested (like father like son). Annibale’s close friend, Galeazzo Marescotti saved him in a daring five-man castle raid. Then, with the help of their Bentivogleschi allies, snuck Annibale back into Bologna, raised up the city militias and noble families, and defeated the Piccinino’s mercenary forces.

All was well—until—Annibale decided to pardon the Canetoli family. The once great Bolognese patricians grew jealous of the Marescotti family and decided to kill Annibale Bentivoglio and all of the sons of Ludovico Marescotti. After brutally stabbing Annibale to death in the street, the city descended into chaos, and the Bentivogleschi rallied around the Marescotti banner and it’s only surviving son—Galeazzo Marescotti. Days of fighting ensued, but in the end, the Canetoli and their Caneschi allies were almost entirely eradicated.

In the wake of this tragedy, the Bentivogleschi regime needed a new figurehead to represent the faction. They tried to implore Ludovico Bentivoglio to take the mantle, but he wasn’t interested in following his extended family in a pursuit that cost them their lives—who could blame him? On account of this, Ser Cola d’Ascoli came through with one of the most amazing ‘rags to riches’ stories in history. A story that provides keen insight into how these facilitators and state policy manipulators vetted their sources.

Sante Bentivoglio:

Shortly after the death of Annibale Bentivoglio, the prominent Florentine signorial statesman, Neri di Gino Capponi, was approached by his friend Angolo Acciaiuoli, this is his personal account of what happened:27

After several months, Messer Agnolo Acciaiuoli took me by the hand and said, “Let us go for a walk, for I need to talk with you,” and we went toward the Serviti, and he said to me, “If you could bring Annibale Bentivoglio, who was such a great friend to you, back to life, would you do it?”

Then I began to laugh and said, “I am not Christ incarnate, who raised Lazarus from the dead. Annibale was cut to pieces, and you ask me if I want to raise him, if I can. It seems to me that you are mocking me.”

To which he replied, “I am not mocking you, but I speak the truth, and I tell you that if you want to, you can.”

And repeating these words to me several times, and still asserting that I had the power, I replied: “Explain this matter to me, for as I loved Hannibal in life, so I love him now, and I will prove it now by being able to do so; but you talk to me of miracles and impossible things, and make me leave this world, saying that I can raise the dead. It is true that I have done many great things for my people, but this seems like madness to me, for I am certain that Hannibal was cut into pieces, died, was buried, and was seen and mourned by many.”

Then Messer Agnolo said: “And it will not be impossible for you, as you believe: hold this and read.” And he showed me a letter of credence from sixteen of the leading men of Bologna, from a Bolognese who is called Ser Cola, and said to me: “Now see, Neri; this man has been to me and told me that Hercules, brother of Messer Antonio Bentivogli and cousin of Hannibal, stayed in Poppi and had dealings with the wife of Angnolo da Cascese, from whom he had a son named Santi; and when you took Poppi, they went with the Count to Lombardy, and then Annibale wanted to take him away from him. Then, at Antonio's request, you arranged for him to enter the wool trade with Nuccio Solosmei. This Bolognese, on behalf of all, concludes that they wish to have this Santi in Annibale's place, out of respect for the House, as they had Annibale. You will make this Santi great, and you will do great pleasure to the Bentivoliesca faction, and you will do for our Community, for he, having been raised in Florence and then becoming great in Bologna, will always be our friend.”

Then I said: “Messer' Angnolo, when you first brought up this matter, you told me it was impossible; but now you tell me in such a way that if things are as you say, not that they are impossible, they must first be well understood and well measured. It is true that Antonio da Cascese is a very good friend of mine, and he raised this young Antonio as his nephew, and he has neither father nor mother; and he recommended him to me and said he was sending him to Florence under my care, if nothing should happen to him. I have done so, and I would do for the young man as for my own son; & Antonio is a rich man, and loves him dearly. He has already given him 300 florins on that workshop. The first thing I would like is to be certain that he is Hercules' son; once this is clear, we can better advise on this matter.”

Then Messer' Agnolo wanted me to get together with the Bolognese man, who told me about the room that Hercules had made in Poppi, and how he had told many people that this Santi was his grandson. I wanted to know if his mother had mentioned anything about it, either while she was alive or after her death, but finding nothing, I asked several people who had known Hercules, and they said that he was the spitting image of him, and that Hannibal had said to him affectionately, “You are one of us. Go, and I want you to come home soon,” and other similar things. So I decided to speak to the young man and tell him this story, and then report it to Antonio da Casceso to hear his opinion. When I told the young man everything, he was upset by his mother's shame and said that he had never heard anything about this case except for what Hannibal had done to him when he passed through Bologna, which he had not thought about until now. A letter was written to Antonio, and Santi went there. He replied to Santi that he had never heard anything about this case and had never been displeased; however, he asked him to return to Florence and not to discuss this matter with him, but to inform him of my opinion.

At this time, more Bolognese came to Florence to see him, and they all looked at him with great devotion, asserting that he looked just like Hercules, and that he could not deny being his son. Cosimo de' Medici spoke of this case, and some of them, in the presence of Messer' Agnolo, Cosimo, and myself, asked to speak to the young man; and because Cosimo had the gout, they wanted me to take him to his house. The Bolognese, however, insisting that he was the son of Hercules, told him all the above and more, and begged him to go with them. and told him that they would be pleased if he would follow them, and that they would put him in possession of the house, furnishings, and possessions that had belonged to Hannibal, and would give him other things, and offer him endless comfort and support. The young man was eighteen years old and shy. He replied with a few appropriate words. Then Messer Agnolo, Cosimo, and I remained alone with him, and Cosimo said to him: "See, Santi, if you are the natural son of Hercules, nature draws you to Bologna and to great things. If you are the son of Agnolo da Cascese, you will remain in San Martino doing small things; therefore, I neither encourage you to go nor discourage you from staying, but I only offer you this conclusion: go and think about what your heart desires, and do what your heart desires, for that will be the true judgment of whose son you are. And so we all agreed to this decision.

And during these discussions, perhaps sixty Bolognese arrived in Florence to see him, and they wanted one of my household to join him. Anyone who saw how earnestly they begged him to go with them would have been amazed, offering to make him a knight, to give him possessions, to have him in place of Hannibal, and many said in place of a lord.

Capponi recounts his assault on Poppi in his Cacciata dei conti di Poppi, and contemporary records corroborate that Conte Francesco Guidi fled to Bologna during Capponi’s pursuit. No doubt Ser Cola d’Ascoli would’ve verified the authenticity of Sante’s patronage, being that he was the prospective ‘natural’ cousin of Annibale Bentivoglio, whom the disgraced Count of Poppi had brought with him in a hope that his presence would curtail favor with the Bentivoglio. It’s fascinating that Sante’s journey then takes him into the hands and good graces of Capponi after his return to Florence, and by way of this connection he finds himself immersed in the powerful Florentine wool merchants guild.

Perhaps the best part about this story is how Agnolo Acciaiuoli confirms Capponi’s loyalty to the Bentivogleschi cause. This went down after a relatively precarious situation in Florence. Factions were split between those who supported the Medici and those who supported the Albizzi families. Capponi’s 1440 campaign alongside Micheletto Attendolo Sforza, ended in victory at the battle of Anghiari over the forces of Rinaldo degli Albizzi and Niccolò Picconino; who was for all intents and purposes the Lord of Bologna at the time. The subsequent quest to punish the supporters of Albizzi’s attempted coup, led Capponi to the county of Poppi where he chased out Francesco Guidi, which resulted in the meeting between Annibale and Sante.28

Despite Capponi’s success in this campaign, Ser Cola d’Ascoli needed to make sure he could be trusted. His source, Agnolo Acciaiouli, was a knight in both Naples and Florence, and an ardent supporter of the Medici cause. In 1434 when Cosimo de’ Medici and his family were exiled by the Albizzi, it was Acciaiouli who kept the Medici informed of events happening in Florence, a service which—when discovered—resulted in his imprisonment, torture, and eventual banishment from Florence. Intriguingly it was Acciaiouli who informed Cosimo de’ Medici that Neri Capponi could be won over to his cause, which came to fruition later in the decade.29

Ser Cola would've known all of this because of his service to the Bentivoglio and proximity to the Picconino and Albizzi, and was looking to vet Neri Capponi's feelings on the transcendent Medici and the crestfallen Bentivoglio before letting him in on the secret of Sante’s origins.

Transition of Power:

Sante Bentivoglio was a fairly contentious regent in Bologna, due in large part to the influence of Galeazzo Marescotti and his mentor Francesco Sforza. His dogged pursuit of the rebellious Canetoli family eventually caused the Pepoli, Viggiani, and Fantuzzi families to rebel. Despite this, he was saved by the gracious administration of Ludovico Bentivoglio and Ser Cola d’Ascoli.

The real problem for Sante was, that his time as regent was limited. Giovanni II Bentovoglio, the son of Annibale Bentivoglio and Donina Visconti, was coming of age and that meant he would eventually need to step aside. This became a major touch point in Bolognese politics and divided the patrician families. Then, in 1462, he unexpectedly died.

The circumstances of Sante's death were deemed natural, but later revelations by the Malvezzi—blood relations of the Bentivoglio and the de facto number two family in the Bentivogleschi faction—and the dall’Agocchie families painted a more nefarious tale. According to them, Sante Bentivoglio was poisoned and murdered. The culprits—Giovanni II Bentovoglio and Generva Sforza Bentivoglio; Sante's wife.

Generva and Sante were never in love with one another, their union was one of alliance, and Sante much preferred his lover Nicholosa Sanuti over his bride, who was fifteen years his junior. After Sante’s death, Generva actually wrote a letter to Nicholosa offering her sincere condolences. Giovanni, on the other hand, by most accounts was infatuated with Generva.30 To make matters more complicated, Sante was trying to send Giovanni to Naples. Some in the Bentivoglio camp, notably Virgilio Malvezzi, thought that this was a ploy to remove Giovanni from the city of Bologna, so Sante could reign as tyrant, and stopped him from going into this prescribed pseudo exile. After this charade, Virgilio made a powerful political message and had Giovanni elected as the Gonfaloniere of Justice, a position usually afforded to elder statesmen—not 20-year-old boys.31 Sources generally differ on what transpired with Sante’s death, and while we generally take a realistically pro-Bentivoglio stance in our writing, in this case I’m going to observe this narrative from the perspective that the Malvezzi and dall’Agocchie families were telling the truth.

At the Behest of Giovanni II Bentovoglio:

The first letter to reach Milan and the Sforza court in the wake of Sante Bentivoglio’s death, on October 1st 1463 was from Virgilio Malvezzi. In that letter, composed October 13th and addressed to Duke Francesco Sforza, Virgilio listed a number of reasons as to why he felt the proposed union between Generva Sforza Bentivoglio and Giovanni II Bentovoglio was a bad idea.32

Then, another letter arrived. This one—also composed on October 13th—was written on behalf of Generva Sforza Bentivoglio. In It, she informed her uncle, the duke, that Ser Cola d’Ascoli was on his way to Milan, and that he had full license to negotiate an arrangement on her behalf.33

This was followed by a third letter, this time bearing the signature of Giovanni II Bentovoglio, with a body and scribal hand identical to that of Generva’s, informing the duke that Ser Cola was on his way to Milan to negotiate on his behalf.34

On the 14th, the Sedici admitted that Ser Cola had gone to Milan for “some things,” and by the 19th, ambassadors from across Italy were involved in the negotiations over what would happen next.35

By then, not only Francesco Sforza, Giovanni II Bentivoglio, Genevra Sforza, Virgilio Malvezzi, Stefano da Nardini, the Sedici, and the papal legate were actively involved in discussions, but also a handful of other important local politically-active patrician men including Prospero Camillo, Lodovico Bentivoglio, Giacomo Grati, Ser Cola de Esculo, Tommaso Thebaldino, Michele Pizano, Leonardo Botte, Sante Hemedes, Galeazzo Marescotti de’ Calvi Malvezzi and Paolo dalla Volta.

—Bernhardt, pg. 89

Suspiciously the Duke was dead-set on the notion that Giovanni II should marry Generva Sforza Bentivoglio. This was appalling to the rest of the Italian world. According to Bernhardt, “He and his patrician friends knew full well that even the suggestion of Genevra was shocking as she was roughly the same age (or slightly older), widowed, and the sexually experienced mother of two children, one of whom could legally compete for Giovanni II’s titles and position. Each of those blemishes on a potential bride would have been extremely dishonourable.” (pg. 90) As the future Signoria of Bologna, Giovanni was at the very least entitled to a wife who was of noble birth, who was younger than him, who was a virgin, and a considerable dowry to boot.

At least, this was the argument that Ludovico Bentivoglio, Virgilio Malvezzi, and Giacomo Grati were making, insisting that the choice of Giovanni’s bride should be handled with reverence and respect. Going as far as to write the duke to say that, “this matter is worse than ever,” and “it pains us to the core that this thing is of such a nature,” concluding that they didn’t understand why he wished to degrade Giovanni with such a proposal.36 They certainly knew what was at stake. Ser Cola d’Ascoli on the other hand, had taken a different approach, and spent most of his time ‘trying to convince’ Giovanni and Generva that their union should go forward.37 This is where we have to pause and ask ourselves—wait a second, didn’t Giovanni and Generva give Ser Cola full license to negotiate their future in matching letters to the duke? Was he acting in the dukes interest or their interest?

That’s odd.

Now the twist. In a pair of competing letters in late November and December, we see the positions of both parties suddenly come together. Virgilio Malvezzi surprisingly shifts course and writes to the duke stating that he has done everything in his power to promote the marriage, which doesn’t line up with his previous objections.38 Meanwhile, Ser Cola reports that he’s working really hard to convince Giovanni II, but he's having some trouble—as the Milanese diplomat Prospero Camillo details, “{Giovanni} was too pushy, he wanted everything to work as he wished, and the nobles began to become resentful and hate him..,” which made Ser Cola’s position more tedious. Ser Cola then met with Generva, and after their meeting, Camillo reported that Sforza was greatly pained and in tears.39

Once Generva had some time to reflect on her meeting with Ser Cola, she wrote a letter to her uncle on the 20th of December, and thanked him for sending Prospero Camillo, then praised the duke for his “benevolence and kindness.” As a sign of her gratitude she sent Francesco Sforza eight of Sante Bentivoglio’s finest horses.40

Then, after further discussions with Galeazzo Marescotti, Ludovico Bentivoglio, Virgilio Malvezzi, and Giacomo Grati, Giovanni Bentivoglio relented and the two wed.41

In the wake of this, Galeazzo Marescotti wrote some telling letters apologizing to the duke for Giovanni’s outbursts and frustrations. The old knight and savior of the Bentivogleschi party cut his teeth as a condottiere in Francesco Sforzas mercenary company, and had a lasting friendship with the duke well after their dog days as dust condottiere. A friendship that staved off the destruction of the fledgling Bentivoglio Signoria a number of times.42

Now, none of this really makes sense. We have so many conflicting interests and bizarre twists and turns. However, if what Sebastiano dall’Agocchie; Giovanni’s treasurer, told Pope Julius II in 1506 was true; here summarized by Elizabeth Louise Bernhardt, “Although most of his accounts were about the family in general, Agocchie introduced the claim that Genevra’s first husband Sante had not died of natural causes but had been poisoned by those closest to him (i suoi piu propinqui).” (pg. 265-266), then allow a moment to postulate an alternative theory outside of the academic constraints that confine Dr. Bernhard.

Giovanni had every reason to kill Sante. He had just come of age, and was 20 years and 8 months when Sante was unalived. Moreover, Sante was trying to push him out and send him to Naples so he could bring his son Ercole back to Bologna and reign in perpetuity. Also—he might’ve had a crush on or was perhaps even banging Auntie Generva behind uncle Sante’s back. Assuming he did off his uncle, Giovanni created a problem. Sante—for all of his faults—was loved by Francesco Sforza, his mentor.43

So, here is an alternative hypothesis—enlivened by Dr. Bernhard’s brilliant research and thesis. Giovanni killed Sante and sent his fixer, Ser Cola d’Ascoli—a man well known to and respected by the duke—to Milan to assuage Francesco of the righteous vengeance he was sure to unleash. Being a rational man, who understood the complexity of 15th century dynastic politics, Francesco relented, but insisted that Giovanni marry Sante’s widow, his niece Generva Sforza. At first Giovanni was okay with that, but became incensed in large part because his faction members were losing their minds over the insult of such an arrangement, then eventually relented when he considered the alternative. That’s why there was no dowry, no pomp or elaborate celebration. That’s why Virgilio Malvezzi changed his tune. Francesco’s forceful negotiation and Ser Cola’s part in making it come to fruition was recompense for Giovanni’s unceremonious murder of his uncle.

Conclusion:

Ser Cola d’Ascoli’s life is shrouded by intrigue and mystery. He was a powerful but shadowy figure who was more likely the recipient and director of intelligence gathering, rather than the man on a mission to acquire or attain it. Still, throughout his life, we can see how having ‘that guy’ can help facilitate a faction scattered to the far reaches of Italy to coalesce and create a familial dynasty in one of the peninsula’s greatest cities.

Alas, on the 10th or 11th of May 1477, Ser Cola d’Ascoli died. His death left a vacuum that was never filled by Giovanni II Bentivoglio. Without the once great fixer and facilitator of the Bentivogleschi faction, the unbreakable threads of the fraternity faltered, and threats from without became less perilous than the threats from within. The 1488 Malvezzi coup and the 1502 Marescotti coup were the death throes of the Bentivoglio Signoria, which saw its inevitable demise in 1506 when Pope Julius II marched his Papal army through the gates of Bologna and put the final dagger in the breast of the Bentivogleschi regime.

The Malvezzi coup, in particular, shook Giovanni II to his core. Afterwards he became paranoid and isolated on account that his closest kin tried to have him murdered in his bed. But that story revolves around our second subject, a man who was not a facilitator, but a collector and a gatherer of intelligence and information. A man who was quietly one of the most powerful people in late 15th century Italy—the legendary Benedetto Dei.

Appendix:

If you want to read more about Generva Sforza Bentivoglio and the wild whims of the Bentivoglio court make sure you check out Louise Berhardt’s, Genevra Sforza and the Bentivoglio: Family, Politics, Gender and Reputation in (and beyond) Renaissance Bologna. It's available for free on the University of Toronto website.

You can find Neri di Gino Capponi’s Memoires in Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, Volume 18.

Works Cited:

Castrignanò, Vito Luigi. TESTI NOTARILI PUGLIESI DEL SEC. XV; Edizione critica, spoglio linguistico e lessico. Spienza Università di Roma. 2015. LINK. Digital.

Muratori, Lodovico Antonio. Rerum italicarum Scriptores. Volume 18. N.p., n.p, 1731.

Bernhardt, Elizabeth Louise. Genevra Sforza and the Bentivoglio: Family, Politics, Gender and Reputation in (and beyond) Renaissance Bologna. Amsterdam University Press, 2023. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.809362. Accessed 15 July 2025.

Capponi, Niccolo. The Day the Renaissance Was Saved: The Battle of Anghiari and Da Vinci's Lost Masterpiece. United States, Melville House, 2015.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Ghirardacci Book 3. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. Digital.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Print.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo I (origini-1499). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

Fortunato, Bruno. Fileno dalla Tuata—Istoria di Bologna; Origini-1521. Tomo II (1500-1521). Costa Editore. 2005. Print.

GOZZADINI, Giovanni, and BENTIVOGLIO, Giovanni. Memorie per la vita di Giovanni II. Bentivoglio. Italy, Belle Arti, 1839.

Mallett, Michael. CAPPONI, Neri; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 19 (1976). Treccani.it. Web.

Castrignanò, pg. 12

1415-1420, Pisa (e altre località toscane): lettere di Angelo da Bari, Cola d’Ascoli Satriano e altri braccianti pugliesi conservate nel carteggio Acciaioli (DE BLASI N. 1982; RAO 1996).

Ghirardacci is a bit harsher on the quality of Offida, stating, “This governor brought with him Baldassare Offidano Marchiano, a very cruel man beloved by the Pope; He was equally with Gasparo da Todi, a most wicked man.” (Rerum Italicarum Scriptoris; pg. 43) to which he later adds, “Seeing to the governor that he has free dominion over the city, the Canetoli having fled with their faction and finding himself having many horses and infantry under his command in the city, he makes Baldassare Offidano, a wicked and iniquitous man, mayor and puts Gasparo da Todi, wicked above all, in charge of the bills.”

He obviously thought very highly of Offida and Todi.

Ghirardacci, pg. 43

Il pontefice manda Daniele da Treviso su o tesoriero et vescovo di Concordia per gover natore di Bologna , il quale alli 6 d'ottobre , il giovedì , viene a Bologna et entra per la porta 5 di strà Maggiore con li soliti honori , a cui le chiavi della città sono presentate . Condusse questo govern atore seco Baldassare Offidano marchiano , huomo crudelissimo et assai favorito dal papa ; era parimenti seco Gasparo da Todi huomo sceleratissimo .

Ghirardacci, pg. 43

Parendo al governatore di haver libero dominio della città , essendo fuggiti li Canetoli con la loro fattione et ritrovandosi havere nella città tanti cavalli et fanti al suo commando , fa podestà Baldassare Offidano huomo scelerato et iniquo et alle bolette vi pone Gasparo da Todi scelerato sopra tutti li scelerati ; et fa tutto ciò per tener e in timore la città et secondo il rio consiglio dell ' Offida . Baldassare passa nel palazzo del podestà et volle per sua guardia havere 200 fanti(.)

Ghirardacci, pg. 43

Fu il governatore con gran festa ricevuto , ma spetialmente da Battista Canetoli , il quale , vistosi abban donato dal duca Filippo e le cose della Chiesa così prospere , fingeva tutta questa allegrezza , mentre 10 che egli havesse per qualche via straordinaria potuto accomodare le cose sue . Il governatore , la sera istessa che egli fece l'entrata in Bologna , mutò li capitani delle porte et ve ne pose altri a suo modo ; et il giorno seguente tutti li magistrati giurono fedeltà alla Chiesa nelle sue mani . Il governatore fa portare la campana delli signori antiani , che tenevano sopra il palazzo 15 loro de ' not ari , nel palazzo ove egli habitava . Di questo mese di ottobre , sendo fatto giudice della mercantia Antonio da Castel San Piero dottore , si cominciò a tenere ragione , la quale per molto tempo avanti non si era tenuta . Il governatore , per conseglio de ll ' Offida , comanda a Battista Canetoli che debba licen tiare tutti i soldati da piedi et da cavallo che egli nella città teneva . Battista promette di 20 farlo , ma poi non ne fa nulla ; anzi tarda di giorno in giorno et finge mille scuse , forse haven do egli in animo di far qualche suo dissegno , perchè aspettava il Piccinino che facea il duca Filippo venire(.)

Ghirardacci, pg. 43

(C)ando che se a questa guisa non faceva , che la città giamai viverebbe quieta sotto la Chiesa . 25 Finse adunque il governatore di poco curarsi più che Battista mandasse via li detti soldati , et frattanto egli secretamente tratta con Fr ancesco Sforza , che era a Medicina , che gli mandi alcune bande di soldati ; il quale tosto gli manda Sigismondo Malatesta con 600 cavalli , et secretamente entrano in Bologna per la porta di San Mammolo . Battista , che intende questo , ripieno di timore di non esser fatto prigione , si rivolta alla fuga , et perchè dubitava 30 fuggendo d'esser seguitato , si vestì di panni alla forestiera , et tolto lo sparviero in pugno et fingendo egli et dodici suoi compagni a cavallo di voler gire a caccia , pacifica mente alli 14 d'ottobre , il venerdì , si partì et passò a Correggio , dove poi da molti suoi parenti et amici fu seguitato , e fra gli altri da Ludovico Canetoli , Baldessera Canetoli cugini di Bat tista , Lippo et Giovanni Muzzarelli , Bonifacio Matasse llani , Bonifacio di Giovanni de ' Prieti , 35 che furono in tutto 200 huomini.

Ghirardacci, pg. 43

Parendo al governatore di haver libero dominio della città , essendo fuggiti li Canetoli con la loro fattione et ritrovandosi havere nella città tanti cavalli et fanti al suo commando , fa podestà Baldassare Offidano huomo scelerato et iniquo et alle bolette vi pone Gasparo da Todi scelerato sopra tutti li scelerati ; et fa tutto ciò per tener e in timore la città et secondo il rio consiglio dell ' Offida . Baldassare passa nel palazzo del podestà et volle per sua guardia havere 200 fanti ; et quivi fa creare li nuovi antiani , che furono questi : Per il quartiero di porta Ravegnana : Jero nimo Bolognini confalloniero di giustitia , Giovanni di Jacomo Isolani , Carlo di Gabbione Gozzadini ; porta San Piero : Gasparo di Marco dalla Renghiera dottore , Gasparo di Barto lomeo Sassoni : porta Stieri : Dionisio di Castello notaro , Pietro Capocchia fabro ; porta San 50 Proculo : Giovanni di Montino dalle Coltre , Pietro Berto .

Ghirardacci, pg. 44

Antonio Bentivogli in questo tempo procura presso il papa di ritornare alla patria , es sendo stato 15 anni et mesi tre fuori di quella ban dito ; et il pontefice considerando che egli molto si era affaticato per farli havere il dominio di Bologna , volentieri glie ne fa gratia et lo rimette insieme con li suoi amici ; il quale alli 4 di decembre , la domenica , a hore 22 , entra in Bologna et subito va a visitare il governatore et poi va alla sua casa a riposare .

This was a faction composed of those who sought outside influence over Bologna. For example, they would rather be a subject of the Duke of Milan, than the Pope.

Ghirardacci, pg. 45

La invidia , che giammai non cessa di spargere il suo veneno nei cuori degl'inquieti et ambitiosi , non manca in questi tempi insieme con la discordia soffiar co 'mantici nel fuoco per accender maggior fiamma , perciochè alcuni de' Maltraversi , cioè : Domenico et Giovanni Isolani , Giovanni di Lignano , Giovanni del Testa Gozzadini et altri assai vanno al governa tore et gli dicono che s'egli brama di conservare la città alla divotione della Chiesa , che bisogna por freno alla grandezza di Antonio , il quale pareva che si volesse pian piano porre a o rdine di farsi signore della città come Giovanni il padre haveva fatto , il che a lui era cosa facile , havendo in mano i cuori del popolo , et che per ciò avvertisce bene alli casi suoi .

Ghirardacci, pg. 45

Queste parole non caderono a terra presso il governatore et l'Offida , ma benissimo le appresero nella mente , et per ciò secretamente volendo provedere a quanto dubitava , ordì un trattato di uccidere Antonio ; et così fece venire tutti li soldati alla città sotto pretesto di voler farli fare la rassegna et ordinatame nte portarsi in piazza . Alli 23 di decembre , il ve nerdì , Antonio , che sicuramente spendeva i suoi passi et anche frattanto pregava il popolo non lo volesse così seguitare per vietare ogni sinistro sospetto , la mattina esce di casa sua per andare al palazzo ad udire la messa et ad accompagnare il governatore(.)

Ghirardacci pg. 45

{E}t seco era Giovanni Fantuzzo , ser Cola et Gasparo Malvezzi ; et giunto alla torre degl'Asinelli , si rivolse 15 adietro , licentiò anche alcuni che lo seguitavano , et entrato in palazzo , sec ondo il solito andò a salutare il governatore et seco andò alla messa.

Ghirardacci, pg. 45

Ora , mentre che la messa si cele brava , li soldati facevano la lor mostra in piazza et Baldassare Offidano manda a domandare Tomaso Zambeccari con avisarlo che seco di alcuni negoti i parlar voleva , il quale venuto a lui , si pose ad artificiosi et longhi ragionamenti seco , aspettando frattanto che successo fosse 20 quel del governatore con Antonio Bentivogli . Finita adunque la messa , il governatore piglia per mano Antonio Galeazz o et il conduce nella sua camera ragionando seco con faccia ri dente et proferendosegli favorevole dovunque egli fosse buono per lui , et di uno in altro ragionamento entrando , aspettava d'intendere se l'Offida haveva a ordine posto li soldati alla piazz a et apparechiati quelli che dovevano por le mani addosso ad Antonio .

Ghirardacci, pg. 45

Uscendo Antonio di camera , venne alle scale di legno ( così eran o in questi tempi ) che scendono alla corte del palazzo , et quivi da 25 armati incontrato , fu fatto prigione ad instanza del governatore et di Baldassare Offida . Disse all'hora Antonio : " Et che ho fatto io ? È forse questa la remuneratione delli merit i miei che la Chiesa mi porge di tanta fedeltà et 30 servitù che le ho dimostraio ? , . Et volendo più oltre parlare , con una fascia gli fu chiusa la bocca e tosto giù della scala il condussero dove li fu con celerità tagliata la testa , la sciando di sè un sol figliolo naturale , Annibale.

Ghirardacci, pg. 45

Et volendo più oltre parlare , con una fascia gli fu chiusa la bocca e tosto giù della scala il condussero dove li fu con celerità tagliata la testa , la sciando di sè un sol figliolo naturale , Annibale . Mentre che si scelerato officio nel palazzo si faceva , l'Offida , acciochè il tumulto non si udisse , fece sonar le trombe quasi che della mostra delli soldati allegrezza facesse ; nè sì 35 tosto la morte di Antonio intese , che egli parimente a Tomaso Zambeccari fece con un pan nicello chiuderli la bocca et nella sala del re Entio ad una stanga il fece impiccare . Po mandò a dimandare otto huomini della compagnia dell ' hospitale della Morte , a ' quali com mandò c he senza cappe di Battuti levassero quei due corpi et li portassero a seppellire ; et così fecero , portandoli a San Christophoro del Balladuro , et gli posero ciascuno nella sua 40 cassa di legno et gli diedero sepoltura .

Ghirardacci, pg. 45-46

Poi manda a pigliare l'arme dalle case degli amici d'Antonio et de alcuni de ' Canetoli, et per dare mantello alla crudeltà fatta, sendo distenuto Cola d'Asco li che era in compagnia di Antonio et era suo cancelliero, il condannò alla morte, et poste le bandiere alle finestre del palazzo del podestà, fece leggere il processo, nel quale si manifestava come Antonio et Tomaso Zambeccari et Cola erano insieme d'accordo di dar Bologna nelle mani del duca di Milano. Et condotto al luogo ove doveva morire, ecco un postiero che con un finto brieve papale venne che commandava che Cola non dovesse morire, et fu liberato. Fu questa nel vero fittione dell ' Offida, col mezzo della quale volle alla città dimostrare che ad Antonio et a Tomaso haveva giustamente la morte data.

Ghirardacci, pg. 46

Morti Antonio et Tomaso Zambeccari , l'empio et crudele Offida saglie a cavallo , et accompagnato da tutti li soldati , va per la città inanimando gli artefici che di niuna cosa te mino , che quello si è fatto era perchè li traditori volevano dare la città al duca di Milano . Poi manda a pigliare l'arme dalle case degli amici d'Antonio et de alcuni de ' Canetoli , et per dare mantello alla crudeltà fatta , sendo distenuto Cola d'Asco li che era in compagnia 5 di Antonio et era suo cancelliero , il condannò alla morte , et poste le bandiere alle finestre del palazzo del podestà , fece leggere il processo , nel quale si manifestava come Antonio et Tomaso Zambeccari et Cola erano insieme d'accordo di dar Bologna nelle mani del duca di Milano . Et condotto al luogo ove doveva morire , ecco un postiero che con un finto brieve papale venne che commandava che Cola non dovesse morire , et fu liberato . Fu 10 questa nel vero fittione dell ' Offi da , col mezzo della quale volle alla città dimostrare che ad Antonio et a Tomaso haveva giustamente la morte data . Della morte di Antonio Bentivogli et di Tomaso Zambeccari non si tosto ne fu il papa avisato , che egli alli 24 di dicembre , il sabbato , fece pigliare l'abbate fratello di Tomaso Zambeccari , che era a Fiorenza , et lo fece incarcerare et non dopo molto lo mandò nella 15 rocca di Narni .

Ghirardacci, pg. 47

In questo tempo il conte Francesco Sforza marchese della Marca Anconitana et capitano della Chiesa con li suoi soldati ritrovandosi al ponte Polledrano in alloggiamento , finì il suo tempo del soldo con la Chiesa . Di esso non poco dubitando Baldassare Offidano , forse dal papa mosso che molto temeva che venisse contro Bologna , si delibera farlo prigione(.)

Ghirardacci, pg. 47-48

(E)t alli 9 di settembre , la domenica , con Pietro Giovanni Paulo capitano delli soldati del papa si parte di Bologna et passa a Budrio dove raguna di molti contadini per pigliare il detto conte alla sprovista ; ma di tutto il fatto avvisato il conte

Muratori; Cronica di Bologna, pg. 657-658

A dì 8. di Settembre Meſſer Baldaſſarre da Offida Podestà di Bo- logna andò a Medefina con Pietro Gianpaolo Capitano del Papa , e con molte genti d'ar- mi del Contado di Bologna . Queſto egli fe- ce con intenzione di pigliare il Conte Fran- ceſco da Cotignola Signore della Marca di Ancona , il quale alloggiava colle ſue genti d'arme al Ponte Poledrano . A dì 10. di Set- tembre il Conte ſi parti , e andò a Cantalo- vo nel Contado d'Imola , e paſsò per ſu le foſſe di Medefina in battaglia . Quando le genti paſſavano , dicevano : O Baldaffarre da Offida , vieni traditore a pigliare il Conte Francesto . A dì 15. Meſſer Baldaſſarre ſi parti da e co- Medeſina , e venne al Ponte della Riccardi- na , e ivi alloggiò colla ſua brigata . Il Con- | te udendo come Baldaſſarre era andato a Budrio , incontanente moſtrò di volere ca- valcare in Romagna , e mandò tutti i fuoi carriaggi a Cotignola . Poſcia mandò un Ca- vallaro a Meſſer Baldaffarre , notificandogli ch ' egli voleva andare in Romagna , e che ſe potea fare alcuna coſa per lui , gli coman- daſſe ; e ſubito montò a cavallo colla ſua gente , e cavalcò verſo la Riccardina in bat- taglia .

Muratori; Cronica di Bologna, Pg. 658

Poſcia mandò un Ca- vallaro a Meſſer Baldaffarre , notificandogli ch ' egli voleva andare in Romagna , e che ſe potea fare alcuna coſa per lui , gli coman- daſſe ; e ſubito montò a cavallo colla ſua gente , e cavalcò verſo la Riccardina in bat- taglia . La mattina nell ' alba del giorno adı 16. aſſaltò il detto campo , ruppelo , e pre- ſero Pietro Giampaolo Capitano del Papa , e pochi ne camparono , che non foſsero prefi . Tutte le genti , che furon preſe , furono lafciate andare a caſa loro , nè fu fatto loro verun diſpiacere . Meſſer Baldaflarre fuggì dentro di Budrio.

Muratori; Cronica di Bologna, Pg. 658

Allora il Conte Franceſco fece chiamare il Maſſaro di Budrio con al- quanti uomini , a ' quali difle : Se voi non mi date queſto traditore di Baldaſſarre da Offida , io brucierò quante caſe ſono in queſto paese , e ſtard tanto qui a campo , che avrollo per forza . Allo- ra gli uomini per paura di peggio glielo diedero . Il Conte ſubito ſi parti , e andò in Romagna a Cotignola , e mandò Meſſer Bal- daffarre in prigione nel Girone di Fermo , nel qual luogo morì miſeramente , come uo- mo ſcellerato e cattivo ch ' egli era . Poſcia laſciò andare Pietro Giampaolo , che venne a Bologna all ' arma di Criſto o della po- vertà .

Ghirardacci, pg. 48

(E) l'Offida si fuggì a Budrio , seguitato dal conte , et qui l'assediò . Poi fe ' domandare il massaro c on li primi del castello su le mura , alli quali il conte fece intendere se non gli presentavano Baldassare Offidano , che egli manderebbe a fuoco et fiamma tutto il loro paese , et che tanto vi terrebbe l'assedio intorno , che havria il castello et che da l più picciolo al 5 maggiore tutti li mandarebbe per filo di spada . Udendo il massaro et gli huomini le spa ventose minaccie del conte , et vedendosi senza speranza di esser soccorsi , presentarono l'Of fida al conte , et il conte , fattolo legare stret tamente , seco lo condusse prigione a Codignola , et essaminato che l'hebbe , il mandò a Ghierono di Fermo della Marca consignandolo a Jero nimo dalla Seda detto il Conte , che era stato servitore di Antonio Bentivogli.

Ghirardacci, pg. 48

Jeronimo dalla Seda detto il Conte , che era stato servitore di Antonio Bentivogli . Il quale , haven 10 dolo nelle ma ni , gli disse : " Pur sei qui , traditore , che uccidesti a torto Antonio mio caro signore ; se lecito hora mi fosse , con queste mani ti caverei il cuor dal petto et a ' cani lo”

Ghirardacci, pg. 48

darei ,. A cui l'infelice et crudele Offida rispose : " Non si deve questo tosto attribuire " tutto a me , ma anche alli Maltraversi”

Ghirardacci, pg. 48

Maltraversi ,. Jeronimo adunque condottolo in Ghierono , fu involto nudo in una pelle di bue di fresco iscorticato et poi sepellito in terra restando solo 15 il capo fuore , et datoli il cibo per molti giorni a misura , corroso et divorato con infinito cruccio , finalmente come crudele crudelmente si morì.

Muratori; Gino Capponi, pg. 1207-1208

Facendo quì menzione d'uno caso strano, parrà fia uscire dalla materia. Essendo mortto Annibale Bentivogli in Bologna, per trattato Eugenio Papa tenne con Batista da Cannetolo: e essendo detto a Annibale da piu suoi amici, che Batista lo ingannava, e che farebbe bene a farla a lui; non rispondeva se non: "Io voglio Batista per fratello, & così gli ho promesso, e giurato, e egli a me: io voglio innanzi essere morto per fidarmi, che si possa dire, ch' io sia traditore." Seguito che Batista diè l'ordine suo; che uno Bolognese richiese Annibale fosse suo compare, e battezzatogli Annibale uno suo fanciullo, quel tale gli disse: Andiamo alla festa, e misselo nell'aguato, dove fu tagliato a pezzi da Bettozzo da Cannetolo e suoi compagni. La parte Bentivoglescafi levò, & il Popolo teneva con loro, e fu preso, e morto, & arso Batista, e più suoi seguaci. Trovandosi dentro Messer . . . . . . da Vinegia Ambasciadore per quella Signoria, e Messer Donato Cocchi pe' Fiorentini, i quali dettono quello favore poterono alla parte Bentivogliesca, rimessa in istato e governo della Città, e cacciata via la parte avversa. In capo di più mesi Messer' Agnolo Acciajuoli presomi per mano disse: Andiamoci trastulando, che io ho bisogno ragionare con teco: & avviammoci verso i Servi, & egli mi disse:Se tu potesse fare risuscitare Annibale Bentivoglio, che ti fu si grand' amico, farestilo tu? Allora io cominciai a ridere, e dissi: Io non sono Cristo incarnato, che risuscito Lazzaro. Annibale fu tagliato a pezzi; e voi mi domandare, fe io lo voglio risuscitare, potendo: è mi pare, che voi mi dileggiate. Di che egli mi rispose: Io non ti dileggio, ma dico davvera: e dicoti, che se tu vuoi, tu puoi. E riandandomi più volte simili parole, e pure affermando, che in me era il potere; gli risposi: Aprittemò questa materia, che come io amai Annibale in vita, cosi l'amo, e dimostrerollo ora in quello potersi; ma voi mi ragionate di miracoli, e cose impossiblili, e fatemi uscire del Secolo, che io possa risuscitare i morti. Egli è vero, che io ha fatto a' miei di molte e gran cose; questo mi pare un farnetico, essendo io certo, come io sono, che Annibale fu tagliato in più pezzi, e morto, e seppellito, e fu veduto, e pianto da molti. Allora Messer' Agnolo disse: E non ti fia impossi possibile, come tu credi: tieni qui e leggi. E mostrommi una lettera di credenza di sedici i principali uomini di Bologna in uno Bolognese, che fi chiama Ser Cola, e dissemi: Or vedi, Neri; costui è stato a me, & bammi detto, che Hercules fratello di Messer' Antonio Bentivogli, e cugino d' Annibale stette per stanza a Poppi, & ebbe a fare con la Moglie d' Angnolo da Cascese, della quale ebbe un figliuolo, che ha nome Santi; e quando voi avesti Poppi, se n'ando col Conte in Lombardia, & allora Annibale ebbe voglia di torgliergliene. Di poi tu a petizione d' Antonio l' acconciò all' Arte della Lana con Nuccio Solosmei. Questo Bolognese per parte di tutti mi conclude, che desiderano questo Santi d'averlo in luogo d'Annibale, e per rispetto della Casa, come aveano Annibale. Tu farai grande questo Santi, e farai gran piacere alla parte Bentivoliesca: e farai per la nostra Comminità; che essendo costui allevato in Firenze, e essendo poi grande in Bologna, sempre ci fia amico. Allora io dissi: Messer' Angnolo, prima quando voi entrasti in questa materia, voi mi ragionasti dell' impossibile; ma ora voi mi dite per modo, che se le cose sono, come mi dite non che elle sieno impossibli, elle si vogliono bene intendere e bene misurare prima. Egli è vere, che Antonio da Casese è molto mio amico, e questo giovane Antonio se l'ha allevato come suo Nipote, e non ha nè padre, nè madre: & a me lo raccomandò e disse lo mandava a' Firenze sotto la mia speranza, se nulla glì occorresse. Io ha fatto, e farei del giovane come di figliuolo; & Antonio è ricco uomo, e porta amore a questo. Già gli ha dato fiorini 300. su quella Bottega. La prima cosa, che io vorrei, si è d' essere certificato, s'egli è figlianolo di Hercules: e chiarito questo posso, noi consiglieremo meglio questa materia. Allora Messer' Agnolo volle che io m' accozzassi coa quello Bolognese, il quale mi disse la stanza che Hercules aveva fatta in Poppi, e come avea detto con molti questo Santi essere suo figlivolo. Io volli sapere, fe la madre o in vita, o a morte n'avea fatta menzione alcuna: e di ciò nulla non trovandone, mi feciono

dire a più, che aveano conosciuto Hercules, che Santi era tutto lui in simiglianza: e che Annibale gli avea detto vezzeggiandolo: tu se' de' nostri: va, che in vorrò, che tu torni presto a casa; e altri verisimili. Il perchè fi prese per partito, che io parlassi al giovane, e dicessi questa Storia, e cosi lo significassi a Antonio da Casceso, & udissine suo parere. Il perchè fi prese per partito, che io parlassi al giovane, e dicessi questa Storia, e cosi lo significassi a Antonio da Casceso, & udissine suo parere. Raccontato io tutto al giovane, egli fi turbò per la vergogna della madre, e disse di questo caso mai non avere sentito cosà alcuna se non l'atto che Annibale gli fo' quando passò per Bologna, al quale allora non pensò ma che ora se ne ricordava. Scrissesi a Antonio, e Santi v'andò. Il quale rispose a Santi, che mai non avea sentito nulla di questo caso, e mai non avea dispiacere; pure che egli torasse a Firenze, e che non meco esaminasse questa cosa, & avvisasselo del parer mio.

In questo tempo vennono a Firenze più Bolognesi a vederlo, e tutti lo guardavano con grandissima devozione, assermando che s'assomigliava tutto a Hercules, e non potea negare l'essere suo figliuolo. E di questo caso parlarono non Cosimo de' Medici, e unllono alcuni di loro in presenza di Messer' Agnolo, di Cosimo, e mia, parlare al Giovane; e perchè Cosimo avea la gotte, vollono lo conducessi a casa sua. Il che quelli Bolognesi a chiarezza, che egli fosse figliovolo d'Hercules, dissongli tutte le sopradette cose, e piu altre, e pregavanio volesse ire con loro, e dicevangli l'essere, e gradigia glie ne feguirebbe, e che lo metterebbono in possessione della Casa, e masserizie, e possessioni, che furano d'Annibale, e darebbongli dell'altra roba, e proserte, e conforti infiniti. Il giovane era d'età d'anni diciotto, e vergognoso. Rispose poche parole & acconcie. Di che Messer' Agnolo, Cosimo & io soli rimanemmo con lui, e Cosimo gli disse: Vedi Santi, se tu sei figliuolo naturale d'Hercules, la natura ti tira a Bologna alle gran cose. Se tu se' figlivolo d'Agnolo da Cascese, tu ti starai in San Martino alle piccole cose; però io non ti conforto, nè sconforto all' andare, o allo stare; ma solo ti fo questa conclusione, che tu vada, e pensi a quello ti tira l' animo: e quello dove penderà l'animo tuo farai, perocchè quella fia vera sentenza di chi tu sia figluolo. E cosi tutti ci accomodammo a questa sentenza.

E duranti questi ragionamenti, ne venne a Firenze forse da LX. Bolognesi a vederlo, e vollono uno di in casa mia accozzarsi con lui: e chi avesse veduto con quanta assezione lo pregavano, che volesse ire con loro, non è nessuno non ne fosse maravigliato, offerendogli farlo Cavaliere, dargli roba, averlo in luogo d'Annibale, e molti dicevano in lugo di Signore.

Capponi, pg. 257

Thus, Guidi had to pull up stakes and leave his ancestral castle at the end of July. He took with him his family and his household furnishings—which were borne by no less than thirty-four mules—in addition to his retinue. Guidi headed to Bologna where he would take up his friend Annibale Bentivoglio’s hospitality, haunted by the sarcastic comment that Capponi had sent to Florence’s rulers: ‘And he can try to trick the bloodhounds, finding out what it means to betray Your Lordships, thus becoming an example for all others.’ The entire Casentino was threafter directly governed by Florence, which allowed the city to control not only the passes over the Apennines and a series of strategically important castles but also the woodlands that had been one of Guidi’s chief sources of revenue.

Capponi, pg. 134

The efforts to suppress the opposition had had somewhat limited success: the only illustrious victim they’d claimed had been Agnolo Acciaioli, a die-hard Medici supporter, who’d been imprisoned, tortured and banished to Cephalonia in February 1434 for having stayed in touch with the Medici during their exile. As his biographer Vespasiano da Bisticci reported, Agnolo had managed to destroy the incriminating correspondence before being arrested, but rumors nevertheless circulated that Rinaldo had intercepted a letter from Acciaioli to Cosimo in which he not only described the situation in Florence rather critically, but also advised Medici to make friends with Neri Capponi ‘because I don’t know a better man than him, and he will suit your purposes perfectly.” Regardless of whether these rumors were true or false, they summed up the widespread feeling in Florence; besides, Rinaldo already knew Neri Capponi posed a great danger.

Gozzadini, pg. 8

La morte di Sante Bentivogli avea sciolto dai lacci coniugali Ginevra Sforza , che ancor nell ' april della vita , e adorna di sin- golare avvenenza contraccambiava teneramente l ' amore che le portava Giovanni.

Ghirardacchi, pg. 180

Sicchè per amendue queste cagioni Santi il voleva mandare alla corte ; et di già erasi disposto Giovanni , et havevasi posto le stringhe alle braccia , come era il co stume militare di questi tempi , le quali da Virgilio vedute , egli che era et prudente et savio , conosciuta la tramma di Santi , istrassegli le dette strenghe con dirli che a modo veruno non si lasciasse da Santi persuadere di partirsi dalla patria , ma che constantemente dicesse voler stare 40 in essa , avvengachè egli era stato con tante fatiche reserbato dalle mani de ' nemici et poi con tanta diligenza nudrito , affinechè al tempo determinato pigliasse il primato della fattione benti volesca per sua conservatione . Il che Giovanni appieno fece . Morto adunque Santi et fatte le sue pompose essequie , Giovanni fu creato confalloniere di giustitia , di quella età che detto habbiamo , et fu particolare favore questo , perciochè niuno 45 saliva a tale dignità s'egli non era di matura età .

Bernhardt, pg. 84

“After Sante’s death, Genevra’s position in Bologna immediately became precarious. Although her father was still alive, her destiny was again largely in the hands of the duke of Milan. Genevra composed a letter to her uncle on 13 October, the same day that Virgilio Malvezzi wrote to express his concerns about a Sforza bride for Giovanni II.”

Bernhardt, pg. 84

“This is the first letter we see of Genevra’s. The fact that she wrote to the duke reveals she was well aware of what was happening and how limited her options were. She wrote to the duke to announce the arrival in Milan of Bolognese agent Ser Cola, sent on behalf of nostri magnifici regimenti (the Sedici). She then added that beyond his usual public commissions, Cola was being sent to discuss some things in her name. She asked Francesco to grant Cola full and undoubted faith and to speak with him as if she herself were there; she then entrusted herself to him.”

Bernhardt, pg. 84-85

“The next day Giovanni II also wrote to the duke about the arrival of Cola and worded his letter in nearly identical fashion. Giovanni II noted that Cola was being sent to Milan to speak not only about public commissions but also about issues beyond them, especially about himself.”

Bernhardt, pg. 85

One day later the Sedici announced Cola’s departure for Milan, again to discuss “some things.”

Bernhardt, pg. 91

Less than one week later, a letter was sent to the duke from eminent Bolognese patricians Lodovico Bentivoglio, Giacomo Grati and Virgilio Malvezzi. They reported that they had spoken with Camillo about the marriage proposed between Zohane de Bentivoglio e la Mag.ca Ma. Zenevra and had entertained the idea with due reverence and respect. They continued that they had been thinking about the matter together and were writing together to show the firmness of their collective opinion. They saw the idea of the match to be simply horrible (questa materia peggio disposta che mai) and they would not and could not say more about the topic (et in somma non li volemo ne possemo dire altro). They warned the duke from their hearts that the situation was of that nature (doleci insino al core che questa cosa sia di tal natura) and declared again that Giovanni II was a most devout servant and good young man (Messer Zohanne e devotissimo servitore e bon figliolo). Because he and they had been so true to Milan, they could not understand why the duke wanted to degrade Giovanni II and the city with such a proposal. They wished to conclude the matter of a spouse for Giovanni II but they clearly wished to erase the idea of a marriage to Genevra Sforza from the duke’s thoughts (voglia impore silentio a questa praticha e levarsi dela mente questo pensiero).

Bernhardt, pg. 92

On that same day, 1 December 1463, Ser Cola de Esculo wrote the duke about his mission in Bologna. He had in fact been sent there to comfort Giovanni II and to convince him to marry Genevra.” He reported that he had been working hard in his attempt to convince Giovanni II. He did not find him willing to marry Genevra for certain reasons related to his own magnificence and because of the objections of his most important relatives and friends.

Bernhardt, pg. 92

Virgilio Malvezzi wrote another letter to the duke on the same day.” He first addressed his personal concerns about his own son Giulio who was soon to marry a young and honourable daughter of Marco Sforza.”! In the second part of his letter, Malvezzi explained he did everything he could to promote the marriage plan between Giovanni II and Genevra but that in the end, it did not work. He declared his desire to obey the duke in every affair and that he was perhaps his most faithful servant in the entire city of Bologna before entrusting himself to the duke. Sucha declaration offered a sample of Malvezzi’s latent desire to surpass Bentivoglio—which can also be seen in the enormous wedding celebration he would soon offer his son who succeeded in marrying the honourable Sforza girl. Malvezzi’s desire could have been simmering from as early as 1459. Ian Robertson discusses the Felicini-Canetoli crisis of that year as part of the basis for the Malvezzi crisis and conspiracy, which would take place nearly thirty years later in November 1488.” Perhaps from that time onward, Francesco Sforza began trusting and relying on the Malvezzi as much as or more than the Bentivoglio.

Bernhardt, pg. 93

He then admitted that he had seen Genevra the day before. He had seen that she was greatly pained and in tears, that he discussed Ser Cola’s meeting with her, and that he had extended

Bernhardt, pg. 94

In late December, Genevra decided to compose a letter to her uncle. On 20 December, she wrote thanking the duke for having sent Camillo to her for advice and comfort.”® She thanked the duke infinitely for his benevolence and kindness. To buttress her desires and to gain additional sympathy from her uncle, she gifted him eight of Sante’s finest horses.” She entrusted herself and her children to him with her entire heart. She told the duke that she had sent Camillo back to him with a message that she hoped he would receive in full faith as if she were speaking herself. Unfortunately, details of what she sent through Camillo as her personal message remain unknown.

Bernhardt, pg. 95

Pizano and Botta together responded to the duke on 16 January with news that Giovanni II Bentivoglio was willing to obey the duke and consider marriage with Genevra.'** On the same day Galeazzo Marescotti wrote from the camera di Zohanne.'®° Marescotti was a local hero who had freed Giovanni II’s father Annibale I from prison at Varano and who helped set the Bentivoglio into a position of power in the early 1440s. Marescotti wrote that Giovanni II believed that for some disrespect the duke had insisted on offering him Genevra, but now with his soul, and with the advice of his friends, he would consent to marrying her. To show some of Giovanni II’s resentment, Marescotti did not go as far as naming the bride. Instead he referred to her simply as the woman whom Prospero Camillo was here to represent.

Bernhardt, pg. 96

Galeazzo Marescotti composed a second nearly identical letter four days later. He declared he was writing to repeat what had been said in other letters recently sent to Milan.'°’ He repeated Giovanni II’s intention to marry Gianevera (she was finally named), and that he would do so happily and voluntarily. Marescotti explained the reason for Giovanni II’s change of heart: he had been literally “alienated from any other hope” after having heard the ultimate response from Francesco Sforza through Ambassador dalla Volta, i.e. that Genevra was the only available Sforza bride. Marescotti continued that Giovanni II was willing to follow faithfully all future orders from Milan, together with all of his friends and the Bentivoglio clan. Lodovico Bentivoglio, Giacomo Grati and Virgilio Malvezzi composed another joint letter to the duke, repeating the same outcome of the long negotiations: Giovanni would be happy to follow the duke’s wishes, and he would literally put himself under the duke’s wings and wil 1.'°8 Not one word was mentioned about Genevra Sforza’s dowry. There remains nothing about payment, possible transferral or existence. It was not part of the Sforza offer. Giovanni II could not have fared worse in his marriage negotiations. Not only did he have to marry his aunt and accept the dishonour the match represented but he also had to accept her without a dowry.

Ady, pg. 42

Within a year of Francesco Sforza’s accessioin as Duke of Milan, Sante had established himself in his confidence. In 1451 Francesco Sforza was writing to Sante as to a trusted friend, and treating him as his confidential agent in his dealings with the lords of the Romagna. Galeazzo Marescotti, who had seen service under Francesco Sforza, relized that Sante had supplanted him in the ducal favour: ‘Your illustrious lordship has placed his thoughts and hopes here in others than myself’, he wrote in December of 1451. The intimate relations between them lasted as long as a Sforza ruled in Milan or a Bentivoglio in Bologna.