Roll a doobie, grab a bag of Funions, and pour a glass of an obscure European beer—we’re talking Philosophy!

In 1484 Alessandro Achillini, age 21, graduated from the Alma mater Studiorum Uiversità di Bologna, with a degree in Philosophy and Medicine. Alessandro, according to Paolo Giovio (one of his former students) spent three years of his undergraduate studies at the Université de Paris, where he likely developed an interest in Averroism and the ideas of Siger of Brabant, before returning to Bologna to argue his thesis. Right away, Alessandro had distinguished himself, and was afforded the opportunity to become a lecturer in Logic (1484). He was later given license to lecture in Natural Philosophy (1487) and Theoretical Medicine (1494) and earned his doctorate in both disciplines between 1497 and 1506.

Alessandro developed a sterling reputation, being heralded as the second Aristotle by his peers and was one of only a handful of native Bolognese lecturers that was able to stay and compete with the big names that the university recruited to come and lecture from across Christendom. This was in large part because the Alma mater Studiorum Uiversità di Bologna had a student driven approach to its organization, where students were free to choose between competing lectures in similar subjects, and the university would deliberately schedule those lectures at the same time to gauge the student’s interest in the lecturer. Then the university would grant a higher salary to those with the greatest attendance or penalize lecturers who fell short of expectation.

Achillini would remain in Bologna until 1506, when he was forced to flee the city with the Bentivoglio family. Alessandro had grown up as a near peer of Ercole and Annibale II Bentivoglio, his younger brother Giovanni Filoteo was a year older than Annibale, and it’s likely that Giovanni Filoteo’s 1514 publication, Viridario, (completed in 1504) which contains a passage describing the study of sword and buckler fencing in various assalti is an observation of Annibale’s sala, il Casino, and highlights master Guido Antonio di Lucas pedagogy. Alessandro was a courtier of the Bentivoglio, which means he was often in the presence of Giovanni II Bentivoglio, his sons, and grandsons, attending their banquets, and entertaining their guests—the likes of Dukes, Counts, Marquis, and Popes—with his philosophical prowess. There is no doubt he had a considerable influence on the family, and Guido Rangoni.

Upon fleeing Bologna, Alessandro departed the Bentivoglio cavalcade and made his way to Padua, where he accepted a position as a lecturer in Natural Philosophy, and competed with the famous Italian-Aristotelian Philosopher, Pietro Pomponazzi. The university of Padua wasn’t as prestigious as the Alma mater Studiorum Uiversità di Bologna, but it was the epicenter of Aristotelian debate in Renaissance Italy. Pomponazzi and Achillini clashed often, both men wielding the sword of Averroism, while Alessandro chose to bear the shield Siger of Brabant’s doctrinal approach and Okam’s nominalism, Pietro took up the dagger of Alexander of Aphrodisias and the Stoics to complete his Aristotelian dialectos. Achillini’s short two year stint as an exile in Padua left a lasting impression on Pietro Pompanazzi, who upon Achillini’s passing in 1512, took up his sparring partners post at the University of Bologna, in honor of his old friend.

Achillini’s philosophical approach greatly focused on the idea of universals and particulars. The concept of universals derives from Platonism, and this idea can be reduced in this way; if things share an attribute, a feature or a quality, this common property between those things is known as a universal. A red apple and a red rose share the particular quality of redness, and this idea of redness is a universal. Universals are metaphysical concepts that transcend space and time and can’t be destroyed. If you were to break a red cup, you wouldn’t destroy the universal of redness or cupness, only the object that exemplified those universal qualities. Particulars are simply defined as individuals or entities that exist and occupy a certain space in time, everything that surrounds you; the cup, the rose—you, reading this article are a particular. A good way to break this down is, a particular exists in itself, while a universal exists in something else.

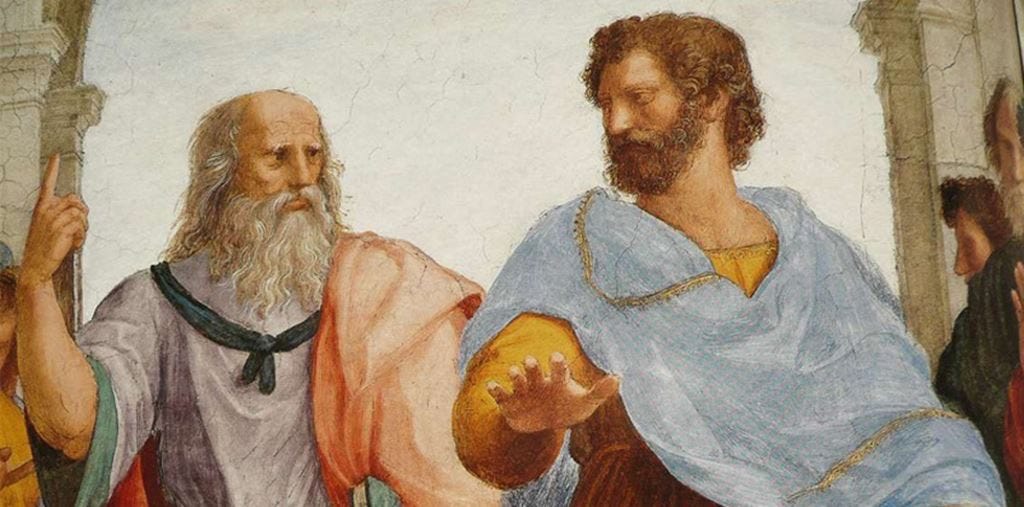

In Platonism, universals are representations of Forms, which are perfect exemplars of commonly observed qualities. Thus, the universal red derives its properties from the Form red and the universal cup derives its properties from the Form cup. These Forms, according to Plato exist completely outside of space and time, and possess a higher reality than their earthly counterparts, which are malleable, imperfect, and finite in their existence—like our broken red cup. Plato’s examples of Forms include; Dogs, Human Beings, Mountains, Colors, Justice, Beauty, Courage, Love, ect. In Platonism, philosophy was the pursuit of understanding these Forms, and to him the existence of Forms solved the problem of universals, that is, the concept of Forms answered the question, how can one thing in general be many things in particular.1

Plato’s pupil, Aristotle disagreed with his master’s idea of Forms, what he termed universals before things (universalsia ante res), and instead argued for universals in things (universalia in rebus).2 More succulently, according to Bob Hale, Aristotle argued that “while there are universals, they can have no freestanding, independent existence. They exist only in the particulars that instantiate them.” So, the red particular of an apple presupposes the universal redness that it shares with rose. While Aristotle didn’t believe in transcendent Forms, he did believe that beings, all imperfect copies of another, develop toward a perfect form unto themselves, and that it is the goal of the individual to find out what that is, and strive for that perfection before they begin to decay. This empirical, rather than ethereal, perception of forms was unique to Aristotle’s approach to logic, his conclusions were based on observation, and were therefore universal.

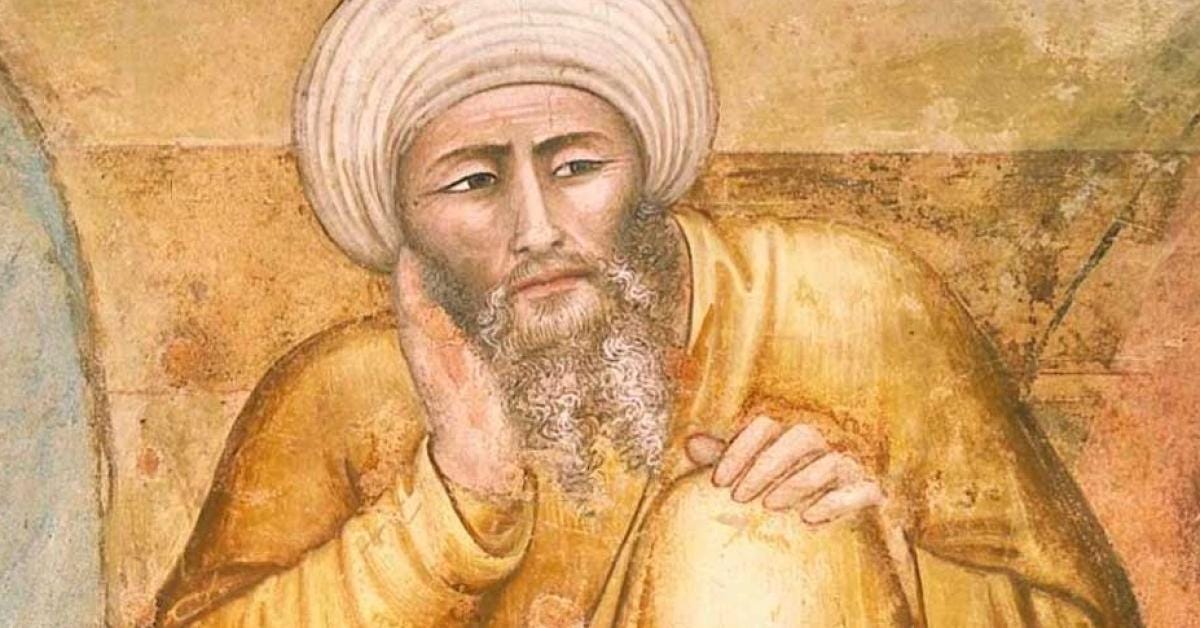

This notion was taken to the extreme by the 12th century Muslim philosopher Ibn Rushd, or Averroës, whose reflections on Aristotle and Plato became wildly popular between the 13th and 16th centuries. Latin Averroism, the prevailing offshoot which sprung up in European universities, argued the assertion that reason and philosophy were superior to faith and knowledge founded on faith; that natural truths were sufficient. Averroës tried to reconcile his Muslim faith with his knowledge of philosophy, and concluded that the aim of philosophy was to, “establish the true, inner meaning of religious beliefs and convictions.” (Rosenthal) The three main tenants that arose from Averroism were the idea of universal cognitions or sources of knowledge, what he termed aver roes; which is the material intellect through which all forms come to be realized (and where the philosophy gets its name) and e dater formarum; or the creator of forms, which is the active agent in intellectual reasoning. This led to the ideas that man can manifest their own happiness in life, and the rejection of both moral determinism and the existence of the eternal soul.

This stood in contrast to the teaching of Thomas Aquinas, who argued that reason was capable of operating within faith. This polarity between prevailing influences during the height of the reemergence of Aristotelian thought throughout the European sphere, highlights the divide between the direction of the secular universities and ecclesiastical seminaries at the time; where secular scholars preferred the scholastic empowerment of Averroism, and ecclesiastic scholars preferred the apologetic dynamism of Thomasism. Dante Alighieri, who was an admirer of both schools of reason, postulated that Aristotle was, the embodiment of total human knowledge—“the master of those who know.” (Minio-Paulello)

Therefore, it’s of little wonder that Dante put the beleaguered 14th century Averroest philosopher, and heretic, Siger (pronounced: Cee-jay) of Brabant, in his fourth sphere of paradise, among his 12 illustrious souls. Sieger, while a professor at the University of Paris, argued that one thing can be true through reason, and the opposite can be true through faith.3 Basically, if I observe that the great 20th century poet Bret Michaels is correct, that every rose has a thorn, and I therefore associate roses—let’s call them red roses—with pain, while you, dear reader, have only ever perceived a red rose as an object of beauty, both of our collective experiences are a part of the greater cognition of the truth of a rose, but my forlorn power ballad can be true just as your unsullied admiration for the form of the rose can be true as well, therefore, there can be two truths, derived from the collective cognitive truth. Siger used this to justify the truth of Aristoteles empirical and dogmatic realism, with the wonders of his Christian faith. This heterodoxy got him excommunicated and marked as a heretic, for arguing two truths. It also brought Siger into the crosshairs of Thomas Aquinas, who in his work, De Unitate Intellectus Contra Averroistas, thoroughly repudiates these ideas as contradictory, and impossible, even if they are a faithful—albeit extreme adherence to the doctrines of Aristotle.

In steps William of Ockham.

Ockham said to hell with the complexity, the universals and Greco-Islamic realism. God made the rules, he's not subject to the rules, universals don't explain the existence of God, they're simply a manifestation of language, devices conceived by man to generalize particulars—an attempt to understand the mystery of creation. He argued that there are only particulars, no realities or cognitions, but only individual quantifiable, measurable, tangible things. Ockham was the champion of empiricism. This was inherently an even stricter dogmatic approach to Aristotelian philosophy, and it gave rise to a new form of thinking called nominalism. Many of you will be familiar with Ockham’s razor, which posits, plurality must never be posited without necessity (Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate), or more simply the least complex explanation is the most likely explanation.

Now, that might’ve been a lot, but it was important for me to layout because in this piece we’re going to explore what I believe is Alessandro Achillini’s influence on Achille Marozzo, and how his philosophy may have come to shape the tactical framework of Marozzo’s system of fencing, and to understand Achillini we needed to understand his influences. Now let’s take a deeper look at Alessandro Achillini.

Achillini in his work, Quaestio de Universalibus, he tackles the two questions posed by the 6th century philosopher Porphyry; namely whether universals are only in the intellect, and whether universals are real. On a base level we can reduce Achillini’s thoughts with a few simple quotes. First he states, '“We experience that the universal is in us while we think and every [kind of] knowledge presupposes it.” (Matsen) From Achillini’s reduction of this point using a device known as dubia, or doubts, Achillini answers the first question by concluding that universals only exist in the mind. He later confirms this in his work on Aristotelian physics, De Physico Auditu, published in 1512, by stating, “A universal in act is in the intellect.” (Matsen). To answer the second question Achillini discusses the assertions drawn by the medieval philosopher St. Albert, who claimed that universals were material, in his rebuttal he states, “I do not agree with this opinion [of St. Albert the Great], first, because I do not posit universals to be real except potentially…” (Matsen). He takes what can be argued to be a modified nominalistic approach. Achillini was an ardent scholar of Aristotle, and his—like almost all medieval scholars—primary mode of accessing Aristotle’s works came through the Latin writings of Averroës, his doctoral development brought him in contact with and eventually bore the influence of Siger of Brabant and William of Ockham. This hybrid analysis of the concept of universals speaks to the pluralistic approach of Siger, while his nominalistic presupposition of the experience of particulars influencing the existence of universals, aligns with the teachings of Ockham.

It’s through this challenge of Porphyry that we get to the purpose of this article, which is, how Achillini’s philosophy might be related in Marozzo’s schermo. Porphyry’s question on universals touches on a subject that we’re probably all familiar with, his challenge on the questions of universals hinges on Aristotle’s supposition of genera and species, which is the foundation for modern taxonomy. Achillini’s reduction of this point leads to a nice analogy that fits with a common trope seen throughout Achille Marozzo’s Opera Nova. My argument is simply this, that Achille Marozzo or even di Luca before him—through the supposed influence of Alessandro Achillini—applied the concepts of universals and particulars in the schermo, or system of fencing, we know as Bolognese fencing. In the introduction of Marozzo’s, Opera Nova, Book Two, Capitolo 85, he states the following:

“I want to make it understood that when a man delivers a blow, he can only throw three kinds of attacks naturally, namely a mandritto, a riverso, or a stocatta. There are those who will say that there are more than these aforesaid three attacks that can be done, and I will confirm to you that indeed there are; that is, there are many kinds of attacks, but regardless of whatever blow is thrown in the beginning one can’t do any other than those aforementioned three.” (Swanger)

Quite simply, there are three ways to attack, from the right, from the left, and through the middle with a thrust. In order to cognitively process how your opponent is trying to strike you in enough time that you can make the appropriate response—this is all you need to recognize. This is nominalism at it’s finest. Let’s use Porphyry’s problem of universals, and Aristotle’s genera of species, along with our modern conception of taxonomy to draw an analogy. If I see a Tiger in the woods, I can follow two cognitive paths, I can say, “Oh shit, that’s a tiger!” and seek shelter as quickly as possible, or I can say, “Oh shit, that’s a tiger, I wonder if it’s a Bengal or a Siber—ghhhahheawww”. Is the speciation of a given thing in a moment of potential harm necessary? Do I need to identify whether a blow is impuntato, infalso, traversato, ect. to assume the requisite defense? This is the question that Marozzo presumes to tackle. He says, “There are those who will say there are more than these aforesaid three attacks that can be done, and I will confirm to you that indeed there are” (Swanger) and this is supported by the anonymous author of MSS Ravenna M345/M346, whose author states, “for the attacks one can make with the sword are infinite and innumerable, and so too are the ways in which the swords may be found…” (Fratus). Marozzo then follows this with, “that is, there are many kinds of attacks, but regardless of whatever blow is thrown in the beginning one can’t do any other than those aforementioned three.” (Swanger)

This statement echos the disposition of Achillini’s thoughts on universals, “We experience that the universal is in us while we think and every [kind of] knowledge presupposes it.” (Matsen) That is, the particulars presuppose the universal, as in Ockham. Therefore, Marozzo, using reductionist logic has narrowed down the key particular of a given attack to three main characteristics, a mandritto (cut from the right), a riverso (cut from the left), and a stocatta (a thrust). Because all attacks will originate from one of these three particulars, before taking on further particulars to become what composes the compound universals defined by more complex nomenclature. Thus, in defense, when cognitive acuity is key, a nominalist approach will prevent analysis paralysis, and provide the best response for a given attack.

Marozzo repeats this assertion frequently throughout his text, maintaining that the ways in which your opponent can attack are limited to his nominalist reduction. Then, given the weapon set, he prescribes an appropriate response to one of these three particulars. Now, a given defense will at times have an asserted variation based on it’s height, ie. Marozzo’s response to a mandritto to the leg may differ from an attack to the head, ect.. They may also vary depending on the guard that a fencer has assumed prior to their opponent delivering an attack. I don’t think that either of these two conditions invalidates Marozzo’s assertion, in that some of the defenses are universal of the height of the attack, and the body mechanics of a preemptive attack differ based on their directionality. When it comes to guards, Marozzo is assuming a presupposed understanding on the various ways to defend from specific guards, it is his pedagogical model laid out in his introduction, and through Book Two, Capitolo’s 138-143. Therefore, when one assumes a specific guard, they should have the requisite understanding of the best defense for any of the three attacks.

This notion in itself creates an interesting parallel with Antonio Manciolino’s, Opera Nova, where a thorough reading will present the scholar with an observation I like to refer to as Manciolino’s box, or to ward off my students jokes pertaining to the movie Seven or the Saturday Night Live skit, dick in a box; Manciolino’s triangle.

Looking at sections in Manciolino’s text, mainly pertaining to his defensive actions in Book One, Book Four, and Book Five, one may notice a consistent approach to how the author prescribes certain defenses from various guards. Manciolino systemically tackles four main attacks that follow an attempted thrust from your opponent; a mandritto to the head, a mandritto to the leg, a riverso to the head, and a riverso to the leg, at times giving two variations of leg defenses which I believe are predicated on the measure of the opponent. Let’s take for example his plays from Coda Lunga Alta, in Chapter One of Book Four, Manciolino’s response to a Mandritto to the leg (where the opponent has passed with the thrust and the cut to the leg) has you turn your false edge underneath your opponent’s attack, and slice a riverso to their leg; this is true of Chapter 5, Sword and Cape, play 6, where you give the same response. Likewise, the defense for a riverso to the leg (where the opponent passes with the thrust and passes with the riverso to the leg) is synonymous between chapters. The same is true for cuts to the leg where the opponent doesn’t pass with the cut, and the prescribed defense is to cut to the opponent’s sword arm with the same nominal attack (ie. riverso to the sword arm if you’re defending against a riverso, and mandritto to the sword arm if they cut a mandritto).

The same reductionist schermo can be observed in his defense against high attacks, where, returning to our box or triangle, Manciolino generally defends in one of three ways or in three distinct guards; Guardia di Faccia, Guardia di Testa, and with a Mezzo Mandritto. Utilizing these three defenses Manciolino defends against the Mandritto, riverso, fendente, stramazzone, stoccata, ect.; the actions from Guardia di Faccia can be done with the true edge or the false edge depending on your position or guard when it’s time to execute your defense.

Back to Marozzo, a concise application of these best practices, outlined by Manciolino, can help enrich and fulfill Marozzo’s abbattimenti and assalti. Take for example Marozzo’s third play with the sword and Targa, Capitolo 128:

“You ended the previous section, the second part, in coda lunga e alta. From there, reveal a slight opening to your left leg, which is your forward one, so that your enemy will have a reason to throw that same mandritto that I spoke of above in the second part. However, as he throws the blow, send your right foot forward, a bit toward your right, and as you do so, extend your sword beneath your targa, closely together with it so that the false edge of your sword touches your targa and the point of your sword faces toward you enemy’s right, and make your left leg follow behind your right one in this parry.” (Swanger)

Marozzo’s follow-up is different than Manciolino’s in the continuation of this play, which is fine, the point is the symmetry in defense. Check out this quote from Marozzo’s Capitolo 142. where he discusses the defenses from Porta di Ferro Stretta, “but I tell you truthfully that quite a lot of parries can be performed, namely falsi, with mandritti or riversi of such a nature as seems best to you, or you can parry in Guardia di Faccia or Guardia di Testa, or in some other fashion that I have taught you.” (Swanger) He basically walks us through Manciolino’s box. In effect the purpose of these guards and actions, is to allow you to defend in a way that permits a quick counter attack, as Manciolino says:

"Just as you should not strike without parrying, you should not parry without striking—always observing the correct tempi. If you were to always parry without striking, you would let your timidity plain to your adversary, unless you were to push the opponent back with your parry, in which case you would show your valor. Correct parries, in fact, are performed going forward and not backward; in this manner you cannot only reach your opponent, but you will attenuate his blow against you…” (Leoni)

A great example of this, and one that truly sets the Bolognese system apart is the use of the false edge parry. Marozzo in Capitolo 142., regarding Cinghiara Porta di Ferro Stretta, says this of the false edge parry, “whatever the situation, counseling him that he should parry with his false edge, since as you know, with a falso once can strike and parry in the same tempo.” (Swanger) and Manciolino affirms the praise of the false edge thus, “Those who parry the opponent’s blow with the false edge of the sword will become good fencers, since there can be no better or stronger parry than the ones performed in this manner.” (Leoni)

In conclusion, Alessandro Achillini started what was believed to be an Ockhamist revolution in the city of Bologna in the 1490’s, having a work on the 14th century philosopher dedicated to him, in 1494, by a student named Marcus de Benevento, who thanks him in his dedication for introducing him to Ockhamist ideas. Marcus de Benevento would continue to release two more works by Ockham in Italian, completing the collection in 1498. This timeline aligns well with the known foundation of the di Luca tradition in Bologna, with both the founding of il Casino and di Lucas first appearance in a Bolognese census occurring in 1496. This coupled with Achillini’s known participation in the Bentivoglio court, and his brother, Giovanni Filoteo Achillini’s poetic observation of both di Luca’s school and Guido Rangoni, a contemporary, classmate, and the patron of Marozzo, who was also the grandson of Bologna’s signoria, Giovanni II Bentivoglio, provides us with tantalizing evidence that the nominalism in defense purported in Marozzo’s treatise, and evident throughout the rest of Bolognese tradition, was likely influenced by the philosophy of Alessandro Achillini. That is, the reductionist statement, “I want to make it understood that when a man delivers a blow, he can only throw three kings of attacks naturally, namely a mandritto, a riverso, or a stocatta” (Swanger) echoed throughout Marozzo’s work, fits nicely with the Ockhamist approach of nominalism, and the continued use of nomenclature laden attacks using genera and species beyond the set particulars, highlights the plurality of Achillini’s other great influence, Siger of Brabant.

Next we’ll look at Viggiani, and how Achillini’s legacy not only supplied Viggiani’s muse Boccadiferro, but Achillini’s posthumous publication on Aristotelian physics might've influenced his discussion on tempo.

Works Cited:

Rosenthal, Erwin I.J.. "Averroës". Encyclopedia Britannica, 2 Aug. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Averroes. Accessed 12 September 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Latin Averroism". Encyclopedia Britannica, 28 Apr. 2009, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Latin-Averroism. Accessed 12 September 2023.

Hale, Bob. “Realism”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 Nov. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/realism-philosophy. Accessed 12 September 2023.

di Bruno, Nardi. “Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 1”, Achillini Alessandro. 1960. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/alessandro-achillini_%28Dizionario-Biografico%29/. Accessed 12 September 2023.

Minio-Paluello, Lorenzo. "Aristotelianism". Encyclopedia Britannica, 9 Jan. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aristotelianism. Accessed 12 September 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Saint Thomas Aquinas summary". Encyclopedia Britannica, 29 Apr. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/summary/Saint-Thomas-Aquinas. Accessed 12 September 2023.

Taylor, Richard C.. “Averroes’Epistemology and its Critique by Aquinas”. e-Publications@Marquette, 1999. https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1295&context=phil_fac. Accessed 13 September 2023.

Matsen H. Alessandro Achillini (1463-1512) and Ockhamism at Bologna (1490-1500). J Hist Philos. 1975;13:437-51. doi: 10.1353/hph.2008.0016. PMID: 11617337.

Fratus, Stephen. “With Malice and Cunning: Anonymous 16th Century Manuscript on Bolognese Swordsmanship.” Lulu Press. 18 February 2020.

Swanger, Jherek. “The Duel, or the Flower of Arms for Single Combat, Both Offensive and Defensive, by Achille Marozzo.” Lulu Press. 22 April 2018.

Leoni, Tom. “The Complete Renaissance Swordsman: Antonio Manciolino's Opera Nova (1531)” Freelance Academy Press. 27 May 2015.

Matsen, Herbert Stanley. Alessandro Achillini (1463-1512) and His Doctrine of "universals" and "transcendentals": A Study in Renaissance Ockhamism. United Kingdom, Bucknell University Press, 1974.

Siger was accused of teaching "double truth"—that is, saying one thing could be true through reason, and that the opposite could be true through faith. Because Siger was a scholastic, he probably did not teach double truths but tried to find reconciliations between faith and reason. Wikipedia: Siger of Brabant