As boys fencing with the sword and buckler young Guido and Hugo Pepoli had learned the essential truth of combat: victory comes to the one who best controls time and space. This same axiom was just as applicable on the battlefield “where the calculation of space and time appears as the most essential thing,”[1] as it was in the fencing hall. It was just one of many ways in which the contests of armies resembled the contests of individual fighters.

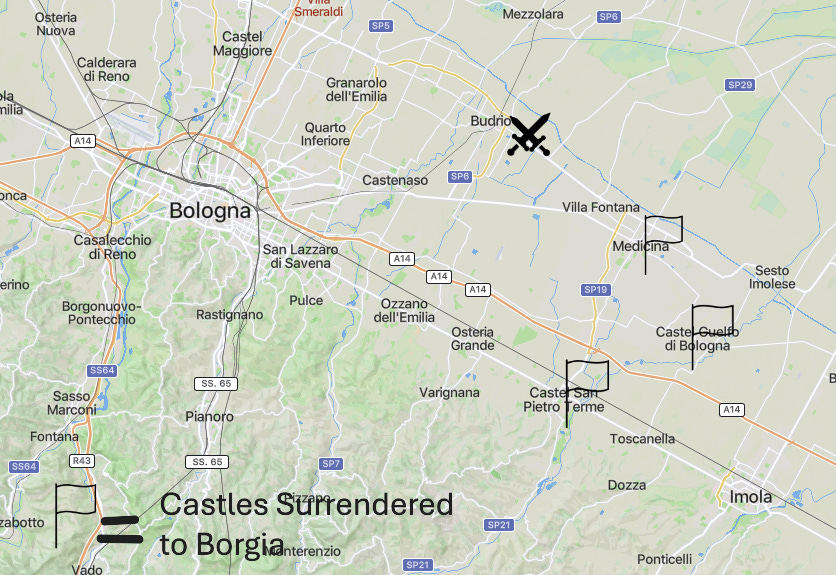

The boys were not the only ones privy to this lesson. Cesare Borgia had grasped it and mastered it well. On April 24 of 1501 the city of Faenza surrendered to the duke and its young lord Astorre placed his life into Cesare Borgia’s hands. Before settling on a new government for the town, Cesare started his next conquest. While the Bolognese government was dithering over how best to deal with Borgia’s conquest of Faenza, the young conqueror sent his general Vile Vitelli to attack Bologna. Vitelli led a combined force of infantry, cavalry, and artillery into Bolognese territory to seize the strategic border castle of Medicina.

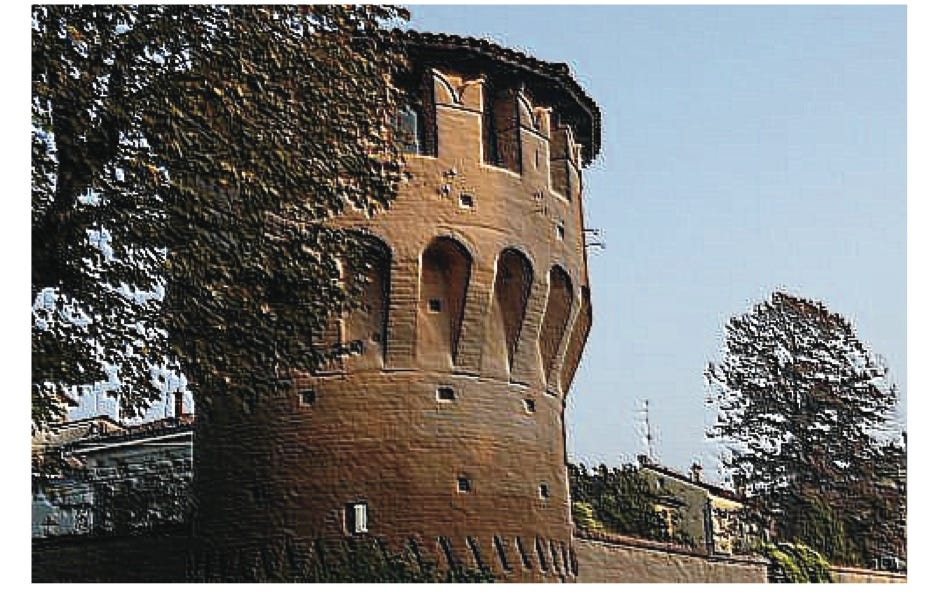

Recognizing the importance of this castle to the defense of Bologna, Grandpa Bentivoglio had sent a mercenary company to reinforce the garrison. Despite these reinforcements the Bolognese fortress ran up the white flag at the approach of the enemy.[2] Borgia’s general spared most of the garrison,but he ordered the death of captain of the mercenaries.

Vile Vitelli’s men beheaded the captain and put a stone in place of his head, then threw the lifeless corpse into the moat around Medicina.[3] It was a chilling message of what Guido Rangoni and his Bentivoglio relatives could expect if Borgia’s men captured them. As Machiavelli confirms that it was Borgia’s deliberate policy to exterminate the families of those lords whom he had dispossessed, lest they seek to come back and claim his lands at a time when he was weak.[4]

With Medicina captured, Vitelli dispatched riders to raise Hell throughout the territory of Bologna.

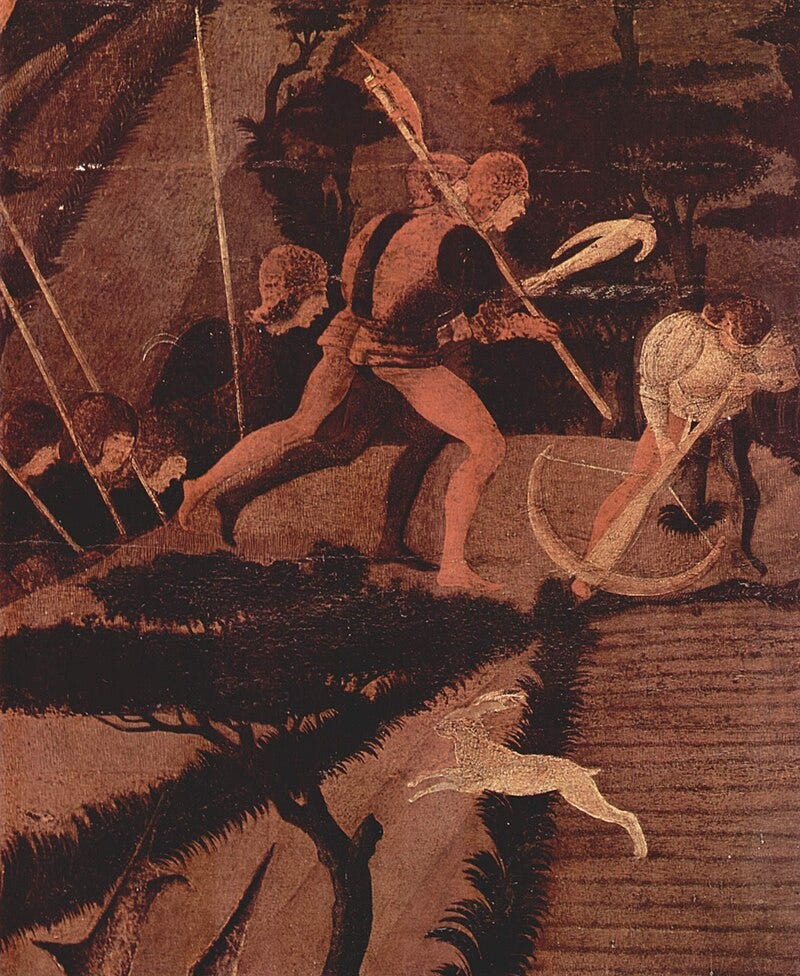

The response of the people of Bologna to the invasion of their territory was immediate and overpowering. “Without even waiting for the bells to summon them,” the men and the militia of Bologna took up their arms and gathered in the plazas of the city. They came from Bologna proper, from its suburbs, and from the more distant parts of the territory. There were city boys with crossbows and long guns.[5] Country boys came with their spears and billhooks.[6]

The great lords of the territory had also come with their retinues of men-at-arms, riding fierce war horses and resplendent in gleaming silver armor. Probably none of the great lords had as large a following as those that followed the silver and black checkerboard banner of the Pepoli. Hugo came back to Bologna with his family’s followers and their allies from the mountains, and there was a cheer as the people gathered in the main square of Bologna to see them.

Seeing the city under threat and seeing his family in danger, we can imagine the great relief that young Guido Rangoni experienced at the sight of so many of his countrymen rallying to the cause of the Bentivoglio in their time of need. Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli had known one another as distant relatives and as rivals, but now, in the main square of Bologna the silver shell and the checkerboard standards came together as brothers in arms. The young men were full of fight and like so many in Bologna, disgusted that so many castles had been lost without a fight.

They wanted to take the battle directly to Borgia, to drive way away the invaders and reclaim the ancestral castles of Bologna. They were not alone. Somewhere between twelve and fifteen thousand men had come to Bologna to offer their swords and their mood was fierce and determined.[7] Many crowded into and around Bologna’s main square and called on Grandpa Bentivoglio to set them loose like a pack of wild dogs on Borgia’s men.

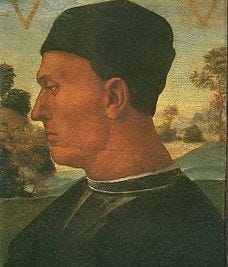

Grandpa Bentivoglio had left his palazzo to stay at the palace of the lords on Bologna’s main square. He now appeared in a window so that all could see him. He wore dark, somber colors as per usual, but his face bore a buoyant and optimistic expression.

The great buzz of chatter filling the air now grew quiet, as men turned an ear toward him.

Grandpa Bentivoglio opened his arms in welcome. “My friends it is good to see you. These are dark days. As we speak enemy riders ravage our lands, they burn our homes and farms. They threaten our women and our children and demand that we place our heads in their hands. Well, what do we say to that?”

With one voice the crowd cried, “No!’

“No, indeed. Do not fear my friends, I will see us through these dark days. I am finding mercenaries for us and our allies are getting ready to send troops to our aid. I have troops to watch our gates and walls, and I am sending reinforcements to protect our fortresses in the countryside.”

Then Grandpa Bentivoglio motioned for two strong attendants to come forward. They hoisted up a strong box and tilted it a little forward for the crowd to see. “I have a hundred thousand ducats here to spend in defending our city. And if that is not enough, I know where to get a hundred thousand more.”

There was silence and admiration in the crowd at the sight of so much gold. The strong men tilted the chest forward a little too far and a handful of golden coins fell out through the open and descended towards the crowd like little drops of rain. Men jumped up to snatch the coins out of the sky as they fell.

“When will we bend our knee?” Called Grandpa Bentivoglio.

“Never!”

But the crowd had its own ideas about what to do. Morale was high and many wanted to take to the field now. “Let’s fight now!” One person shouted.

“To arms!” Cried another.

Grandpa held out his arms. He had extensive experience as a condottiere in his own right and knew that enthusiasm was no substitute for experience and that a militia would fare poorly in the open field against professionals. He lifted his arms up and shouted, “Patience, my friends. Now we will guard our ramparts and tomorrow we will see the enemies’ backsides.”

Then Grandpa Bentivoglio drew his sword and held it aloft and shouted the traditional war cry of Bologna. “Sega! Sega!”

The whole crowd cheered back with wild abandon. “Sega! Sega!”

Soon the whole plaza, the whole city and the area around Bologna echoed with the cry of “Sega! Sega!”[8] Borgia’s spies among the Bolognese noted this and came back to the duke with word of the multitude who had come to back Bologna and their vocal support for the Bentivoglio.

He mulled over the idea of giving up the attack. The people of Bologna had come out in force and determination. Furthermore, he could expect them to fight with some skill. Bologna was known as being one of the premier locations in Italy to recruit infantry.[9]

Cesare Borgia’s allies among the Bolognese had told him the people were against the Bentivoglio and now he saw that he had been lied to.

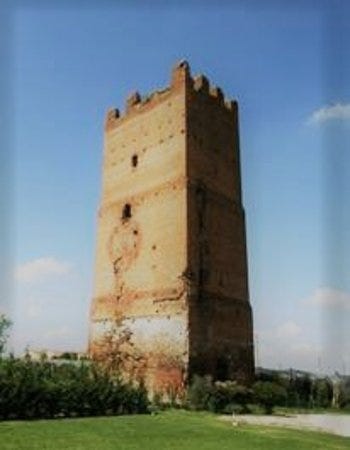

But he had momentum and tried to keep riding it. He sent Vitelli from newly-conquered Medicina to capture the critical fortress at Budrio.[10] But Grandpa Bentivoglio had foreseen this and reinforced the garrison of this castle. Vitelli’s forces ran into a literal and proverbial brick wall at Budrio and the Bolognese drove them off. Vitelli had to tell Cesare Borgia that Budrio would not be taken easily and could only be conquered by a drawn-out siege.[11]

Since he could not conquer the Bolognese, Cesare Borgia now sent an ambassador to negotiate with the Bentivoglio. Grandpa Bentivoglio and the senate of Bologna wanted to put on a convincing display of strength for their enemy. So, they ordered the main road from the east to be lined with troops on either side of the ride – a distance of 4 km (2.5 miles).

The line of infantry continued into the city along the ambassador’s route. Once he reached the main square, he came to see the men-at-arms serving the Bentivoglio: hundreds of knights on their horses in parade formation, armor gleaming in the spring sun, so many lances held aloft it looked like a small forest of barren trunks. The banners of the commanders fluttered in the breeze: the red and gold saw of the Bentivoglio, the red and white stripes of the Pio, the checkerboard of the Pepoli, the golden lion of the Marescotti, and of course Guido Rangoni’s own silver shell.

Guido Rangoni sat his horse proudly before his men, glad that Cesare Borgia had seen fit to ask for peace with Bologna but disappointed that he would have a chance to add glory to his name fighting off the foreigner.1 Borgia’s ambassador stopped for Guido and his men and Guido looked at him with disdain.

The ambassador looked at the company assembled in the square and said to Grandpa Bentivoglio, “You are the most fortunate man in all of Italy.”[12]

They worked out a deal whereby Cesare Borgia would return the castles he had taken in exchange for one crucial Bolognese fortress that stood in his lands. The Bolognese would also provide a mixed force of nearly 1,500 soldiers for Borgia’s upcoming expedition against Florence. This included 1,000 infantry under the command of Ramazzotto whose defense of Budrio had impressed his former opponents.[13]

As a special “bonus” Orsini gave Grandpa Bentivoglio letters sent by members of the Bolognese family, the Marescotti, to Cesare Borgia. In these letters some members of the Marescotti family offered to help Cesare Borgia take control of Bologna. This would prove to be less a gift and more a poison pill that Borgia foisted on the Bentivoglio.

Then Borgia’s army, reinforced by a contingent from Bologna, swept into the territory of Florence. There Vile Vitelli once again led the charge, “scouring the adjacent territory, destroying wheat crops, and cutting down trees and vineyards. He plundered everything. Particularly, he abducted young girls and women and sent them to the whore’s market in Rome.”[14] The Bolognese and their womenfolk could be happy that the same treatment was not being visited upon them.

The letters from the Marescotti family to Cesare Borgia were a red-hot bombshell for Grandpa Bentivoglio. The big question of course was how should he react to it? If he reacted with too much violence, he would alienate his people. If he reacted with insufficient force, his people would seem him as weak and so be more likely to conspire against him and his family. The issue was further complicated by familial loyalty – the conspirators were children and relatives of the Bolognese war hero Galeazzo Marescotti – a man who had Bentivoglio family as featured in our article, The Great Escape.

The leading conspirator was Galeazzo Marescotti’s eldest son, Agamemnon. To the Bolognese people Agamemnon was known as a virtuous and wise man. He was already in prison with other major leaders in the plot against the Bentivoglio and Grandpa Bentivoglio decided to let the wheels of justice deal with them.

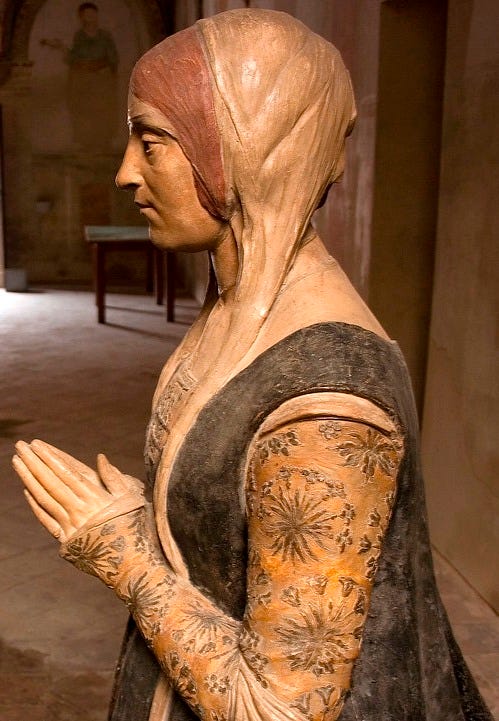

This was not going far enough for Grandma Bentivoglio. Grandpa Bentivoglio was known for a forgiving temperament, but no one would ever say this about Grandma. She was born a member of the proud and tough Sforza family. Her family had gained control of large swathes of Northern Italy through cruelty and treachery. The Sforza were the kind of people who liked to “get medieval” on their enemies, drawing and quartering their opponents or dragging them to death behind horses in the town square until their heads split open against the paving stones.[15] While the Bentivoglio family name would be best translated as “Love,” in English, the Sforza name would be translated as “Strong.”[16]

Grandma Bentivoglio was herself known as a cruel woman with a reputation for icy arrogance.[17] While it would be an exaggeration to say that she wore the codpiece in the family, she was not afraid to go against her husband in the matter of family safety. In 1487 Agamemnon Marescotti had plotted with enemies of the Bentivoglio (the Malvezzi family) to break into the Bentivoglio Palazzo and go to the ladies’ apartments and murder Grandma and her children.[18]

Grandma called for her youngest son Hermes Bentivoglio. The Sforza blood ran far stronger in him than did the Bentivoglio blood. Hermes was as fearless as he was merciless. He was a “pale, melancholic young man,” destined to acquire an “unenviable reputation for cruelty and violence.”[19]

At four in the morning Hermes gathered a group from many of the leading families in town to kill the Marescotti. He sought young men with a penchant for violence. He did not try to recruit young men of honor like his nephew Guido or his cousin Hugo Pepoliceqfor this dirty deed.

Hermes then led these men on a multi-day murder spree. They not only killed Agamemnon Marescotti and his compatriots, but many people whose only crime was being married into the Marescotti family or being in business with him. It was not so much a case of “guilty until proven innocent,” as it was “kill ‘em all and let God sort ‘em out.”

The dirty deed left Grandpa Bentivoglio, “quivering” and “indignant.” He was convinced that he was “finished,” and that the people of Bologna now hated him. To free himself and the city from the stain of murder, he organized a parade through Bologna. The parade leader carried the head of Petronio, Patron Saint of Bologna through the streets.[20] This did little to convince the people that the rule of the Bentivoglio had now transformed into a tyranny.[21] The only thing that would convince them of this was to punish his son and his son’s friends.

But this Grandpa Bentivoglio would not and could not do. He was indebted to them. Everyone in Italy knew that the bargain with Cesare Borgia was only temporary. It would not be long before Cesare sent his army back towards Bologna.

The city and the Bentivoglio were far safer now that the Marescotti were dead.

Bibliography of Works Cited

[1] On War, Clausewitz, from Chapter VIII, “Superiority of Numbers.”

[2] See Ghiradacci, p.303. Also dalle Tuate, p.423.

[3] See www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Vitelozzo Vitelli” in May 1501.

[4] The Prince, Machiavelli, Chapter VII.

[5] Firearms and especially crossbows tended to be associated with urban populations since they often required the services of a specialized craftsman to keep them working. These were also the primary weapons for defense of a city during a siege.

[6] Here is a weapon the Bolognese were particularly known for. There is a note in Sanuto, Vol VIII, col. 401-402 about the Venetian infantry particularly seeking Bolognese billhooks for purchase. This may have simply been a matter of economy or a matter of preference, but the implication is that the style of the weapon was unique, “And the gentlemen were busy every day buying …. billhooks and pikes, especially Bolognese ones, sold by the soldiers.”

[7] Ghiradacci gives the number as twelve thousand on p. 303. Sanuto gives the number as fifteen thousand in Vol. IV of I Diarii, cols. 29-30. These are large numbers for a simple city state like Bologna and exceed the garrison of Florence during the Siege of 1529-1530 despite that being the capitol of a republic with an extensive hinterland. See Guicciardini, Storia d’Italia pp. 420-421.

[8] The preceding is a dramatization of Ghiradacci description of Giovanni Bentivoglio’s words for the people of Bologna on page 303.

[9] See Mallett & Hale.

[10] The sequence of events is a bit sketchy on this. Clearly Vitelli conquered Medicina before attacking Budrio, but it is unclear how much delay there was between the two events.

[11] Sanuto is the only one who describes this battle. The way the actual battle progressed is unattested and this is simply an educated guess based on the general procedures of sieges that we see over and over throughout this period of the Italian wars and the amount of time Vitelli had available to him.

[12] This episode is described in detail in Ghiradacci on page 304.

[13] Details vary greatly on what exactly was in this deal. Sanuto – who was contemporaneous—says that it was for 1000 infantry. Ghiradacci later describes the force that Guido’s uncle Anton Galeazzo leads on Borgia’s behalf as consisting of “100 men at arms, 200 light cavalry and 200 infantry.” Note that dalle Tuate on p. 254 says that it was 100 men at arms 200 light cavalry (between strattioti and mounted crossbowmen). The comment on Ramazzotto can be found in his page on condottieridiventura.it.

[14] www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Vitelozzo Vitelli,” in May 1501.

[15] See Tigress of Forli, Elizabeth Lev, p.26 & pp.145-146.

[16] This of course assumes that you are matching the Italian names to traditional English surnames.

[17] See “Memorie per la Vita di Giovanni Bentivoglio,” Gozzadini. P.123

[18] Ghiradacci, p.250.

[19] See www.condottieridiventura.it entry for Hermes Bentivoglio. Also see The Bentivoglio: A Study in Despotism by Cecilia Ady.

[20] Gozzadini, p.124.

[21] Ghiradacci, p.306.

This is supposition.