Synopsis:

On December 24th 1443 Filippo Dardi received a letter from Lodovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi on behalf of the Otto dell'Avere, amending the terms of an offer first proposed to the fencing master by a certain citizen; sometime prior to this correspondence. For centuries this letter has been used to delineate certain biographical details about Dardi’s life; eg. the statement, of the same nature as the decree of thirty years ago, has been used to deduce that Dardi started teaching fencing in Bologna sometime around 1412 or 1413.

It is my belief that by further examining the historical chronicles surrounding the subject of this letter, we can draw new, interesting, and perhaps more accurate assumptions about the activity and associations that characterized Filippo Dardi’s life. In this paper, we will explore the lives of Lodovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi, using primary and secondary source material, as well as the events that were taking place in Bologna in the years 1413 and 1443 to better understand what Dardi’s role may have been in those events, and examine various historical figures that may have taken part in, shaped, or facilitated the recorded events present in the letter.

I’m going to simply start this off by linking a few articles that provide a deeper substantive look at the information I’m going to present in this article, and do my best to summarize that information found within those articles for the enjoyment of the casual reader. If you want to understand this material better, here are the requisite links:

Dardi Deeds, Done Dirt Cheap: Part 1

The Great Escape Part 4

Income and working time of a Fencing Master in Bologna in the 15th and early 16th century

Transcription and Translation of Dardi’s letter by Dr. Trevor Dean and Brian Stokes

I am sincerely indebted to Dr. Trevor Dean and Brian Stokes for letting me use their translation in this article, and to Jean Chandler and Stephen Fratus for their keen eyes an interest in making this piece suitable for a wider audience.

The Dardi Legacy

It’s time to take a closer look at the later life of Filippo Dardi. It is widely believed that Dardi, after spending his earlier years teaching fencing in Bologna, eventually published a treatise on fencing and geometry in 1434.1 The only words that remain of Dardi’s thoughts on the subject of fencing come from a brief snippet found in his discussions with the Bolognese government about his salary in 1443:

“(G)eometry, which resembles the skill of fencing because in fencing there is nothing but proper measure.”

— Fillippo Dardi (1443) {Dean & Stokes Translation}

Now, it’s imperative that we take a closer look at this document. It’s been thoroughly analyzed in this amazing piece by Battistini and Corradetti, and a full translation by Dr. Trevor Dean and Brian Stokes can be found here, however I want to take a look at this letter from a different angle. Less about Dardi’s pedagogy, his prices for teaching students with various weapons, and his above-cited words, and angle this more toward who he’s corresponding with; Ludovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi, then we’re going to take a brief jaunt through the historical narrative that directly impacts these discussions, and try to draw some conclusions by examining the wording of the letter as it relates to the contemporary chronicles. Jacopo Gelli asserts that Fillippo Dardi was serving the Bentivoglio, was he right?2

The Tesaurerii or Otto dell'Avere

Let’s start off with Simone Manfredi. He’s a bit of ill represented character in the Bolognese chronicles, Simone is likely from the Bolognese branch of the Manfredi family, the dynastic rulers of Faenza. In Ghirardacchi’s third book, it’s mentioned that in 1440 he attended a special mass in Bologna3, then in 1443 he was elected into the Anziani.4 We also know from other sources, that in 1440 he entered into a business venture—likely a banking venture—with Virgilio Malvezzi, Tommaso Gozzadini {who took over the family bank from his father Nanne Gozzadini}, Nicolò Sanuti, and the Sacrato brothers (Ettore, Paride, and Scipione; members of a junior branch of the Gozzadini family).5 It’s not surprising Simone found himself involved with the tesaurerii or entwined in the financial dealings of the city, alongside his business partners Tomasso Gozzadini, Gaspare Malvezzi (the father of Virgilio), and our next subject, Ludovico Caccialupi.

Following this request Lodovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi, both belonging to a corporation designated by the city council to collect taxes (created in 1440)

{Battistini and Corradetti, pg. 157}

Before we get into Lodocivo’s life, let’s refresh our memories on how this corporation, so named the tesaurerii got started in 1440. And let us start with Raffaelo Foscarari, who had ousted the Papal Legate, Danielle, the Bishop of Concordia, in a coup supported by the condottiere Niccolò Piccinino on 20 May 1438 . Raffaleo was elected as the Gonfaloniere di Giustizia a few days later on the 22nd of May, 1438.6 After assuming the role of leader of the Anziani, Foscarari granted himself sole control of the municipality’s finances on 30 August 1438, for a five year term, which was an unprecedented and unusual power move that clearly conveyed his future intentions, and set the precedent for what was to come.7

To alleviate some of the suspicion surrounding his borderline tyrannical behavior, Raffaelo tirelessly worked to recall Annibale Bentivoglio to Bologna, to act as a figurehead to placate his families now suspicious faction.8 When Annibale arrived, Foscarari tried to leverage the young condottiere into his influence, but after excluding him from every level of civic authority—fearing that he would be too powerful of a political figure to contend with—their relationship soured. Things got worse when Raffaelo desperately attempted to force Annibale to marry his daughter, to cement his authority by uniting their families, telling him, I will send you back to grooming horses as a soldier of fortune, when Annibale refused to comply (Ady, pg. 19).9 Foscarari’s attempt to establish himself as the Signoria of Bologna—requesting the title of Gonfaloniere di Giustizia for life, so he could co-rule with the mercenary captain Niccolò Piccinino—was under extreme pressure from the powerful Bentivoglio faction.

As a result of Rafaello’s failed political machinations, and the brilliance of Gaspare Malvezzi, the Bentivogleschi (the Bentivoglio faction) were able to undermine Rafaello’s authority by striking a deal between the faction’s oligarchs and Niccolò Piccinino, granting the mercenary captain 12,000 lire of bolognini (a sizable sum), which would be subsidized by the city’s elite.10 This corporation, which called itself the tesaurerii, subverted all of Foscarrari’s power and influence, and was designed to reconcile the municipalities finances in the wake of his corrupt overspending. This body was represented by number of notable families, but key figures included; Gaspare Malvezzi, Giacomo Grati, Giovanni Fantuzzi, Girolamo Bolognini, Tomasso Gozzadini, Ludovico Caccialupi, and Bartolomeo Zambeccari, each loaning the government a considerable amount of money.11 Once this was in place, and the deal was finalized with Piccinino, they were given the green light to murder Rafaello Foscarrari.

Standing beside Annibale Bentivoglio, on the fateful day of Foscarari’s assassination, 6 February 1440, in the Via delle Clavature, was our dear friend, and the next subject of this piece, Ludovico Caccialupi.12

We have to start off by discussing Ludovico’s surname, Caccialupi, or wolf hunter—in the pantheon of badass Italian surnames, this one is definitely up there.

Originating from Fano, the Caccialupi family eventually settled in the city of Bologna. Ludovico went to school to study law, and used his education to find a seat in the Anziani, where he represented the Porta Ravegnana district13 { Note: this is the same district that Guido da Manziolino represented as captain of arms in 140214, and the same district that would later give us, Giovanni Manziolino, who was elected into both the Sedici and Anziani, and acted as diplomat to Niccolò Piccinino alongside Gaspare Malvezzi in March of 1440 before taking on a more substantial role in the Bolognese government151617}.

On 14 June 1443, by popular consent Ludovico was selected as a member of the Otto dell'avere, which was an enshrinement of the tesurarii into the Bolognese government.18 It was in December of that year that Filippo Dardi’s negotiation with Ludovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi took place, but before we get there, a lot happens, and before we talk about all of the events that take place between June of 1443 and December of 144319, I want quickly highlight how close Ludovico was with Annibale Bentivoglio, and how loyal he was to the Bentivogleschi faction.

Caccialupi after the murder of Annibale in 1445 became one of the chief diplomats of the Bentivoglio faction. He would go to Florence alongside Ser Cola da Ascoli—a shadowy figure that was likely the spy master of the Bentivoglio—to track down the bastard son of Ercole Bentivoglio (Annibale's uncle, Antongaleazzo’s brother), Sante Bentivoglio, who was set to act as regent and guardian for the young Giovanni II Bentivoglio (the infant son of Annibale) until he came of age.20

They were successful. The boy, raised as a blacksmith’s apprentice, was later taken into the Wool Merchants Guild (Arte della Lana) at the age of 21, by his adopted caretaker Antonio da Cascese, on behalf of the Albizzi family under the tutelage of Nuccio Solosmei (notably the same Florentine guild and familial faction where a di Luca family were prominent figures in rural Arezzo).21 Rinaldo and Luca Albizzi helped prop-up Antongaleazzo and Ercole Bentivoglio after their exile from Bolognese territory in 1423, and would've likely been privy to the Bentivoglio-boy’s dalliances while they were in Florence—though Neri Capponi, Sante’s protector or caretaker and the director of military policy for Florence in the 1420’s {when Atonogaleazzo and Ercole were working as condottiere on behalf of Florence}22, claimed ignorance of the boys origins.23

Sante was armed, clothed, and provisioned by Cosimo de Medici, and left with the parting words, “If you are the son of Ercole Bentivoglio you will desire to go to Bologna and play the part which befits your noble birth; if you are the son of Angelo da Cascese (his adopted father) you will stay at your shop in San Martino and be content with small things.” (Ady, pg.34)

Caccialupi, for his part, under Sante’s reign, would treat with popes, dukes, and princes across Italy, and proved to be a cornerstone figure in the establishment of the permanent Bentivoglio Signoria along with Galeazzo Marescotti, Virgilio Malvezzi, and Lodovico Bentivoglio. Young Sante ended up being a favorite of Francesco Sforza (now Duke of Milan), who constantly wrote to the young Signoria with advice and counsel.24 Eventually, Sante proved to be a key figure in the tripartite alliance between Bologna, Florence and Milan after the peace of Lodi; setting a precedent for later Bolognese diplomacy.

The Mighty Underdog

Let's return to Bologna, 1443, between the time of Caccialupi’s appointment, and the letter written to Fillipo Dardi. Battistini and Corradetti accurately point out that at the time of the letter Bologna was in a state of financial trouble, they had just recently been bailed out by all of the aristocratic banking families in the city (the tesaurerii), but there is something else going on that may have had a more substantive impact on this negotiation. Let’s take a look!

When Annibale was rescued from his imprisonment in Castello Varano by Galeazzo Marescotti, he was first greeted in Bologna by Lodovico Bentivoglio, and the Gonfaloniere di Giustizia Melchiore Viggiani (one of his closest friends, a knight, and the future famed Bolognese ambassador to Rome; likely an ancestor of Angelo Viggiani)25. The Bentivoglio allies that greeted Annibale were armed and ready for battle. They rang the bell of San Giacomo to rally the rest Bentivogleschi to their banners, and marched on the Palazzo del Commune to oust the tyrant Francesco Picconino, who was acting as governor on behalf of his father Niccolò Piccinino.26

What happens next provides deeper context for the importance of Dardi’s work as a fencing master, and in my opinion why he was corresponding with representatives of the Otto dell'avere in the first place. {namely Simone Manfredi and Lodovico Caccialupi}

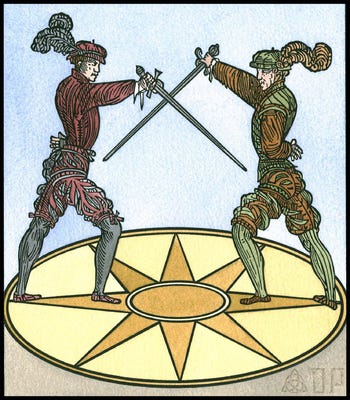

In the 15th century it was rare for an Italian citizen militia to engage in any level of combat outside of a siege where necessity dictated their participation, let alone take on a professional army and win in such a fashion that, “the defeat suffered by the enemy was so complete as not to be remembered in the annals of our history”—as Galeazzo Marescotti recounts.27

After the reinstatement of the Bentivoglio faction in power in Bologna, 5-6 June 1443, the citizens of Bologna were called to serve in a number of capacities. After their daring fight against the Braccesco soldiers of Francesco Piccinino, they were called upon to lay siege to Francesco’s captain, Tartaro da Bellona who was garrisoning Castello Galleria—located in the northernmost corridor of the city—who had 500 men at his disposal and a number of bombards (cannon).28 During this siege, Bolognese citizens from all walks of life cast off their finery or poppers-wares to take up arms against their common enemy.29 One instance, repeated numerous times across sources, deals with one of Dardi’s future colleagues, one, Messer Giovanni d'Anania, an ancient and highly celebrated doctor30, who set aside his doctor’s robes, donned armor, and picked up a shovel to help dig a trench enveloping the Galleria fortress.31

The heroism of the Bolognese people was further exemplified when they banded together to repel the attack of Astorre Manfredi {A Faenza-based relative of Simone} when his company of 400 horsemen tried to cut the Reno canal and then stormed through the Porta Galleria Gate to relieve the Castello Galleria garrison, with the goal of providing a port of entry for the Visconti captain, Luigi dal Verme’s army, who had moved to threaten the city for Niccolò Piccinino and Filippo Maria Visconti, 20 June 144332. The bells of Bologna alerted the citizens of the danger, and over 9,000 residents heeded the call. They attacked the mercenaries occupying the market, under heavy bombardment from the cannon about Castello Galleria, and managed to fight off the professional soldiers, and prevent the rest of Luigi dal Verme’s Visconti troops from entering the city.33

This event so inspired Annibale that he felt confident enough to take his small coalition of professional companies; Piero di Navarino, with 400 cavalry and 300 Infantry (Bolognese), Simonetto Baglioni da Castel San Pietro with 300 {3-800; sources vary} cavalry and 800 infantry sent to the aid of Bologna by the Florentines, Guido Rangoni (the Elder) with 600 cavalry and 200 infantry, and Tiberto Brandolini, the son of Brandolino Brandolini, with 450 cavalry in the pay of the Venetians—totaling between 1,750-2,250 professional cavalry, and 1,300 infantry—and bolster them with an armed militia from the city of Bologna to achieve the unthinkable.343536 On the night before the eve of the Madonna, 15 August 1443, the small Florentine-Venetian coalition, and five to six thousands Bolognese citizens rode out of the city to attack!

Annibale’s gamble paid off, despite Luigi dal Vermes force totaling 6,000 professional soldiers (4,000 Cavalry and 2,000 infantry)37, the Bolognese citizens-in-arms tipped the scale of the battle, and the outcome was a crushing victory.38 Over 2,000 of the 4,000 Visconti horsemen were captured or killed, including 236 men of repute.39 As a consequence, the Castello Galleria garrison, under Tartaro da Bellona, capitulated soon afterward. The hearty holdouts holed up in the old Visconti symbol of tyranny {Castello Galleria} decided it was better to take a hefty sum of cash rather than of trying to fight it out with no relief force in sight.40

To the Victor Go the Spoils?

It seems that Dardi’s efforts in training the city’s youth (Military aged males—up to 2541) paid dividends. Allow me to explain: my hypothesis is that this was a prearranged agreement that preceded and facilitated the success of Annibale’s citizen militia, struck between Dardi and an unnamed member of the Bentivoglio faction. Let’s return to the letter and look at the context clues that help structure this argument:

To your magnificent lordships: magnificent and potent lords, I Lippo son of Bartlomeo Dardi, your most humble servant, petition your magnificent lordships that it might please you to be the instigators of honour and profit to this magnificent city, namely that you might deign to make me a certain honour and benefit, which a while ago was offered and promised to me, not at my request, by a certain citizen, who seemed to want to reward me by this means.

—Fillipo Dardi {Dean & Stokes Translation}

The letter starts out with Dardi basically asking for his due {reward} in an offer that had been promised to him, not by his request, but means of a ‘certain citizen’. To Fillippo this was an honor and a benefit, and this proposal was viewed as a reward by the mysterious benefactor who wished to bestow this upon him. Now, straight out of the gate the thing that stands out the most to me, is the grant to become a lecturer at the Università di Bologna, this is a hefty reward. The role of lecturer, accompanied by the title Doctor, was a noble title in Bologna. It wasn’t just a prestige position, it was a legacy position, that guaranteed the beneficiary and every generation born after 30 years of their ennoblement, the same grant of nobility.

You know, Lippo, that I have decided that for the honour of this city you should have a grant of 200 lire every year from a tax, which, whether it is farmed out or not, the relevant officials should give you the said 200 lire every year…

—Certain Citizen {Dean & Stokes Translation}

This role came with a guaranteed stipend of 200 Bolognese Lire—eventually renegotiated to 150 Bolognese Lire—starting in 1443-44, and then following on from year to year, and reads throughout the document as a guaranteed income, which Dardi subsequently collected until his death in 1463. This endowment was perhaps provided by the precursor of the University dividend of the Gabella Grossa, a tax on goods sequestered from the general tax on citizens in the 15th century to develop the local prestige of Bolognese citizens working at the university that replaced the old collectio—which funded the university through donations, and was distributed by the student body collectives (natios).42

A survey of notable professors at the University conducted by Serafino Mazzetti confirms that Dardi’s tenure started in the year 1443 and continued until his death in 1463:43

1030. DARDI Lippo, or Filippo son of Bartolomeo Bolognese. He was lecturer in Arithmetic and Geometry from the year 1443 to the whole of 1463.

—Serafino Mazzetti

This is perhaps another abnormality based on the way that the Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna typically operated. Where universitas, or student body collectives {framed by members of nations, or natios}, typically had the power to negotiate subject-matter, duration of lectures, and pay for professors; it was a collectively bargained, student and {eventually} instructor run organization. Rarely was a professor guaranteed anything, yet Dardi’s position seems to have existed outside of this framework. Now, this could simply be one of the early hallmarks the before mentioned Gabella Grossa (noted at as tasse deli docturi {Latin} and dacio {Italian} in the letter), but even if it is, despite not being named as such, it’s still interesting that Dardi was one of the first benefactors of this policy.

Next, I want to talk about the certain citizen facilitating this agreement. First, why are they only recorded as a certain citizen? What’s the deal with the anonymity? For that, I think it’s prudent to establish motive. We don’t know the date of the first correspondence that Dardi cites, however the intent is pretty clear.

But you should know that this is only one reason for me doing this for you, as I tell you that the reason is that I want, for the utility of the young men of this city, and for the honour of the state, and for your own profit, I want that you offer your expertise in another fashion than you have in the past as regards the high fees that you take from youths of this city, and therefore I want to set the fees for your plays in my way, that is where you take for the play of the two-handed sword 23 lire, I want you to take only 8 lire, and where you take 7 lire for the play of sword and buckler, I want you to take only 3 lire, and where you take 12 lire for dagger play, I want you to take 5 lire, and where you take 7 lire for stick play, you will take 3 lire and where you take 10 lire for arms play you will take 4 lire, and where you take 8 lire for shield play you will take 3 lire.

—Certain Citizen {Dean & Stokes Translation}

For the utility of the young men of this city and the honor of the state, followed by Lodovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi’s later reply:

{A}nd considering how much benefit rebounds to our city from the expertise of the said Master Lippo, as he is diligent in the art of astrology, and then taking into consideration how much his teaching of the two-handed sword, the buckler and other plays is useful to the young men of Bologna, for their own defence and for that of the public sphere…

—Caccialupi and Manfredi {Dean & Stokes Translation}

For their own defence and for that of the public sphere, both the proactive request, and reactive language of the later reply put a pretty clear emphasis on the training of young men for the honour of the state, and defense of the public sphere. The goal, or motive of this agreement was to increase the number of students Dardi was training, by lowering his rates, with a set cap—requested by Dardi—of 20 students per class, with a prescribed expectation and timeline for the proficiency of each student. Could it be that Dardi was contacted by a member of the Bentivoglio party to work on developing a functional city militia under the guise of lowering his rates with the promise of a guaranteed stipend and a noble title as compensation for his services?

We, Lodovico Caccialupi and Simone Manfredi, report that, having seen the above request from Master Lippo, son of Dardo Dardi, and having examined it and consulted various people about its contents…

—Caccialupi and Manfredi {Dean & Stokes Translation}

We certainly don't have the details about the date or the origin of the original agreement, but from the period 1438-1443, the Bentivoglio faction was preeminent in Bologna, even with Foscarari, and the tyrant Francesco Picconino at the helm. It was a matter of cohabitation between each of the aforementioned leaders and a city dominated by the preeminent families that composed the faction, whether they liked it or not.

Here’s the catch: who in the Bentivoleschi faction would’ve had the authority to make such an arrangement? There were a lot of moving pieces between 1438 and 1443 that we have to track. Between 1438 and October of 1442, this could’ve been Annibale Bentivoglio, from 1438 to 1443 it could’ve been Galeazzo Marescotti or Lodovico Marescotti, or anyone in the Marescotti family. We know it wasn’t Lodovico Caccialupi, because he had to consult with various people as to the authenticity of the claim. With that knowledge, we can look at the construct of the tesurarii or Otto dell'avere, and probably assume it came from outside this council.

Otto dell’avere:44

Giovanni di Tomaso Bianchetti, Bonifacio di Turzo Fantuzzo, Francesco di Jacomo Ghisilieri, Battista di Ludovico Ramodini, Lodovico Caccialupi notary, Urbano di Guglielmo dalla Fava, Facino di Florio dalla Nave, Crescentius di Bartolomeo dal Poggio.

{Ghirardacchi, Book 3, pg. 87}

There are further clues found in both Ghirardacci’s history of Bologna (where he used a compilation of archival records to construct his tome) and Galeazzo Marescotti’s first hand account of the events that took place in Bologna between 1443 and 1445. First, we’ll turn to Ghirardacci, when Zanese is visiting with Annibale Bentivoglio, playing chess with him in his prison cell in Castello Varano, and Annibale tells him that he should seek out Carlo Bianchetti and Galeazzo Marescotti, his most trusted and loyal allies, to tell them about his location:

Annibale tried to make friends with great words and offers, and at the end he earnestly begged him to tell Carlo Bianchetti and Galeazzo Marescotti how he had seen him in irons.

{Ghirardacchi, Book 3, pg. }

Tomasso Bianchetti was on the Otto dell’avere, and there's a chance he had to consult with his brother about the contents of the agreement, but there's a noticeable lack of Bentivoglio, Malvezzi and Marescotti on the council, key figures in the construct of the faction’s hierarchy, but extant in other branches of civic authority. Now, Gasparo and Achille Malvezzi were imprisoned alongside Annibale in October of 1442, while Virgilio would only manage to take his first few steps as a political figure after his father and brother were captured. So, if we're assuming this came after the date when Annibale, Achille and Gasparo were captured, then that reasonably leaves us with Galeazzo and Lodovico Marescotti. Interestingly, Galeazzo has this to say about Bologna during the time of Annibale’s imprisonment:

It is useful to know that among the many friends of Bentivogli who were saddened and indignant by the imprisonment of the beleaguered Annibale, we were above all others, namely my father Messer Lodovico, and {the always good memory of} my brothers, who all in unanimous agreement in that winter, from which they were taken prisoner, until their liberation, we kept ourselves in arms, spending ours without any reserve whatsoever, exposing ourselves to very serious dangers to our lives and personal safety, as all the people of Bologna can ensure.

— Galeazzo Marescotti

To which, later, after the first failed attempt to liberate Annibale, Galeazzo foments:

So we had to return to our homeland desolated by the failed attempt. Seeing that, everyone who was in government in our city disliked me under the orders of Nicolò Picinino, I was neither happy nor safe. But however I resolutely intended either to try the undertaking we had begun again, or to avert fate altogether by arming our men to drive out the Bracceschi enemies, and anyone else who might wish to resist us.

— Galeazzo Marescotti

My hypothesis is that the certain citizen Dardi is referring to is with one of the following. Giovanni Marrescoti, who stayed behind in Bologna and facilitated many of the affairs in the city while Galeazzo freed Annibale from prison, who was himself a capable soldier and rode out with Annibale Bentivoglio to take part in the battle of San Giorgio. Lodovico Marescotti, who staged a violent uprising in the city in 1413 {Coincidentally when Dardi started teaching the art of arms in Bologna—put a feather in this one}, supplying weapons to a number of citizens hellbent on overthrowing the Papal government in Bologna45, then participating in a coup again in 1416 when Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio returned from the Council of Constance, with orders from the Anti-Pope John XXIII {Baldesare Cossa, the Pirate Pope}, to seize the city from the Holy See, and one last time in 1422, where he and some Bentivogleschi roughed-up some Canetoli, which led to Antongaleazzo’s exile from Bologna. Or, it very well could have been Galeazzo Marescotti himself. The most likely culprit in my mind, and the one we’re going to focus on is Lodovico Marescotti, who is noted as having done the following:46

While the Anziani and Sedici sent ambassadors to Visconti to ask for their release, Marescotti and other benevolent gentlemen hired militias to guard the public buildings. {1443}

—Tamba; Lodovico Marescotti

Is this our smoking gun? Let's take a look back at the letter, and see if there are any other context clues that support this narrative. If Lodovico was our certain citizen, had he contacted or worked with Dardi before? Remember the year is 1443.

Also, he wanted for a decree to be issued for me, according to the new agreement, which would be of same nature as the decree of thirty years ago which I obtained from all the regimes of Bologna.

—Fillipo Dardi {Dean & Stokes Translation}

Oh, hello! Remember what happened back in 1413, when Lodovico Marescotti led a revolt in Bologna under the watchful eye of the Papal government, and smuggled weapons into the city—that was also the first time Dardi is mentioned teaching fencing or the training of arms in Bologna was it not? So where does that leave us?

Let’s take a brief look at the affair in 1413, to get a better feel for what happened, and see how it relates to this proposed narrative:

In December 1413 he was involved in a conspiracy against the papal government promoted by some doctors of the Studio, who trusted in the intervention of Gian Galeazzo Manfredi, lord of Faenza. Marescotti assured the conspirators of his support and the supply of weapons, which in fact he seems to have been able to procure. The plot was discovered and its main promoter, Gregorio Gori, was executed. The other conspirators and Marescotti fled, and were sentenced to death in absentia.

Tamba; MARESCOTTI DE' CALVI, Ludovico

Here is the same instance from the Corpus Chronicorum Bolognese, Rerum Italicarum Scriptores, and Cherubino Ghirardacci:

Chronicle A: Pg. 548

On December 13th a plot was discovered in Bologna which included the following:

Miss Guoro de Masino de Guoro

Misser Gratiolo from Tosignam

Miss Ludovigo Marescotto

Miss Zohanne Gascon

Miss Zohanne de Liazari

and many of them were loved, and they had to shout: "Long live the people and the arts; and death to the Church" and some were executed, while the others fled and were banned from Bologna. And there was a call from the Pope to anyone who could have these rebels captured and who would give them over to him, they would have two hundred of ducats.

Chronicle B: Pg. 547

1413 - A treaty was concluded in Bologna on the 13th of December, which led to the infractions, such as:

Meser Guoro de Masino de Guoro

Meser Gratiolo from Tosignane

meser Lodovigo Marschoto

meser Giovanne Guaschone

Messer Giovanne of Liazari, and many of their friends and they cried out: "Long live the people and the arts, and death to the Church" and Messer Guoro was captured and had his head cut off on the 18th of December, and the others fled, and they were banned from Bologna.

Maruscotti Lodovico di Giovanni [Ludoicus Johannis Marescoti] participates in a conspiracy against the Church he knows and runs away (an. 1413), 102, lo. (Pg. 193)

From the 18th December. - Dominus Gregorius, doctor of laws, son of Masini Gori, a merchant, he was beheaded in the audience, and here he was treated against the state of the Church together with the underwritten citizens, here they fled, viz. Ludoicus Johannis Marescoti, lord Agneiolus son of the bastard son of Antonius de Poetis, doctor of laws, lord Johannes Opiconis de Liacarii scolaris. (Pg. 102)

Ghirardacci Book 2: {1413} Pg. 595

(T)he beginning of this year was eventful, both due to the hunger, as well as the death and shedding of blood of many citizens, who could not, or did not want to live peacefully, but were pleased to lay down the honor, the property , and life itself in compromise, with the meddling in the affairs of states, and public governments, with the hatching of treaties, and conspiracies that are extremely difficult to keep secret, as can be seen from many experiences.

They were therefore for various occasions of treaties against the Church to favor the Malatesti, the following were banished or beheaded, that is, Oretto de gli Oretti, & one of his brothers, Friano del Getso, Dolfolo Cartolaro, Ostesano Piantauigne, Giovanni di Landino de 'Peilicani, Giovanni Bellabusea, Goro di Masino Gori, Doctor of Law; Gratiolo di Tolignano, Doctor of Law; Lodovico Marescotti, Doctor of Law; Giovanni de' Liazari with many of their other friends…who in all numbered fifty. With these and other troubles, the Malatesta Lord of Cesena did not cease to find a way to expel the Legate of Bologna.

Given the circumstances surrounding the events of 1443, and Dardi’s request that the stipulations of the agreement mirror the one agreed upon 30 years prior in 1413, we’re forced to find parallels between events. Fortunately, the incredible life of Ludovico Marescotti provides just that. With the decline of the arms societies in Bolognese civic defense in the 14th century, the onus of arming, training, and organizing a militia was shifted to the factional elite of the city. Clearly, Ludovico Marescotti was a facilitator of these affairs for the Bentivogleschi party, as every time the faction was involved in civic unrest during his lifetime, Lodovico was there.

The 1413 affair wasn’t strictly a Bentivoglio affair, as the faction was more-or-less destroyed with the fall of Giovanni Bentivoglio in 1402, and wouldn’t become a powerful entity in the city again until the rise of Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio, Giovanni’s son. However, in 1413 it’s worth noting that Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio was finishing his civil law degree at the University of Bologna {completed in 1414}, and this 1413 revolt was perpetrated by Goro di Masino Gori, Doctor of Law, Gratiolo di Tolignano, Doctor of Law, Gratiolo di Tolignano, Doctor of Law, and Ludovico Marescotti, Doctor of Law.

More research is needed to find the details about what weapons and support Lodovico Marescotti provided for the rebel faction in 1413. I have a feeling the document isn't digitized so it's been moved to the top of my list of things to find in the Archivio di Stato di Bologna. The same goes for the document stating that Lodovico hired militias to guard public buildings, I trust Giorgio Tamba’s research, he was incredibly thorough, and his citations are rock solid, but it would still be nice to present the primary source document for both occasions. I would also like to find records of Antongaleazzo’s time at the University, to see if he was linked to any of the conspirators. Returning to 1443, I want to highlight Lodovico’s words to his sons, when they were first approached by Zanese, as recorded by Salvatore Muzzi, before moving on to the conclusion:

The old knight called to him his sons, Galeazzo, Giovanni, Luigi, Taddeo and Antenore, and thus spoke to them: "With great reason he must be called inhuman and brutal who does not confess the great obligation that man must have to the homeland. She gives what is suitable for earthly happiness: therefore the ancients venerated her with divine honors. And there was a great captain who, while proceeding to war, in its service, did not want to consult any oracle, saying that dying for the country was an excellent omen. Now, oh brave sons, that City in which we were born and to which we owe so much, has become the nest of tyranny: and that Prince {Francesco Piccinino}, whose justice we have implored, who enjoys our ignominious servitude, to add the name to the titles of his domination the illustrious of the City of Bologna. But such inhumanity cannot last. God will transfer his possessions from one to another people; Filippo will be the last of the Viscontis, and he will not die with the glory of having his sole foot in our dear homeland. Rest assured, the Piocinino will be taught how to govern well with an iron lash: and you will teach him; you, who exhort and inflame us to free Annibale Bentivoglio from Varano's cells, to then free Bologna from oppression with him. Which undertaking, although difficult, is not hopeless - nor impossible. Where there is greater difficulty there is greater glory; and you would achieve it by freeing Hannibal and chasing the Duke's minister from his nest. Your efforts (and sorry that due to old age I cannot take part in them) will not be without reward, earning you the gratitude of your homeland. Furthermore, it will always be said that the Marescotti people descended into the world to make their homeland free and happy; and all of you, my children, will have immortal fame, and you will hand down glory of name and virtue to your posterity; what is highly prized by those who are not brutes, but noble spirits made in the image and likeness of God.

—Lodovico Marescotti (Muzzi, pg. 288)

Conclusion

In December of 1443 Filippo Dardi wrote a letter to members of the Otto dell’avere, asking them to follow through on a promise for a reward or honor and benefit proposed by a certain citizen, the service that he provided was the training of military aged males in the art of arms for the honour of the state, and defense of the public sphere, this was to be arranged in the same nature as the decree of thirty years prior, in 1413, and facilitated by lowering his rates.

Given the historical context surrounding the events of 1443, and 1413, and the evidence presented, that Lodovico Marescotti and other benevolent gentlemen hired militias to guard the public buildings, during the 1443 uprising, and Lodovico Marescotti had conducted a similar operation in 1413, I think it's fair to conclude that our certain citizen is Lodovico Marescotti, and the services rendered to the state by Dardi were for the purposes of training militias in the city of Bologna.

Dardi delivered on his end of the bargain and trained a suitable fighting force that far exceeded expectation. Upon the complete liberation of Bologna from the Picconino tyranny, and the full re-establishment of the Bentivoglio led government, Dardi requested that the council uphold their end of the bargain, which they did, with minor adjustments to suite the financial needs of the city. Obviously, Dardi didn't object, because he became a lecturer at the university, and would remain so until his death in 1463. Dardi’s recorded tenure at the university, 1443-1463, as recorded by Mazzetti in his survey of notable professors, aligns well with this accord.

While there is no definitive proof yet, Dardi’s words placed in their historical context paint a interesting narrative as to why he negotiated his first contract in 1413, then again in 1443. They also highlight the purpose of the Bentivogleschi art of fencing in the city of Bologna, a city rife with factional violence.

Afterward

Sadly, in my estimation, Dardi’s treatise on fencing was likely destroyed in 1508 when the Bentivoglio Palazzo was burned to the ground, along with di Luca’s Opera Schermo. I imagine if we had Dardi's treatise it would've been dedicated to Antongaleazzo Bentivoglio, and would've had lessons on fencing with the two handed sword, sword and buckler, dagger, stick or stave, and sword and shield, among other weapons. Given what little we have left to work with, the question becomes, is Dardi’s legacy inherent in the Bolognese fencing tradition?

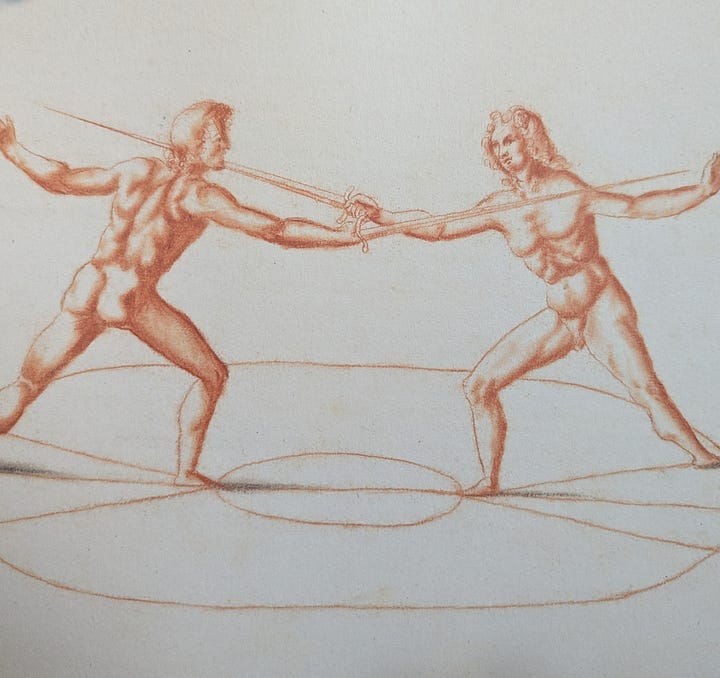

It’s worth asking what made Dardi’s deduction, geometry conforms to the art of fencing because the latter is nothing else than measuring itself, so impactful? Didn’t Liechtenauer say, “All arts have length and measure.” Was Dardi a visionary or just a nascent observer? The only way to really suss-out this information is to look at Marozzo, and Manciolino’s thoughts on the subject.

Antonio Manciolino says:

Fencers who deliver many blows without any measure or tempo may indeed reach the opponent with one of their attacks; but this will not redeem them of their bad form, being the fruit of chance rather than skill. Instead we call gravi & appostati those who seek to attack their opponent with tempo and elegance.

— Antonio Manciolino {Leoni, pg. 111}

To which Marozzo adds:

Always teach your students how to walk from guard to guard—forward, backward, and sideways, obliquely and in any other possible manner. Do this especially with sharp weapons—that is, with targa, rotella, large buckler, single sword, and cape, sword and dagger, and two swords. Teach them to let their hand be in agreement with their feet and vice-versa, or else your instruction will be defective. If you think you may forget footwork patterns, I will include a drawing that will show it to you with clarity. Remember to teach footwork over the segno where there are not any people you don't want there, especially students from other schools, to prevent your fundamentals and your teaching from being plagiarized.

— Achille Marozzo {Leoni, pg. 10-11}

Of course, the segno did get out, thanks to the fame of Marozzo’s Opera Nova, we see it taught in some form or variation in Palladini (late 16th-17th century), Ghisiliero (1587), the later Florentine tradition of Docciolini (1601), and in the 1561 publication of Joachim Meyer. This could have been the pedagogical device that made the Bolognese or Bentivoglio tradition so unique.

Of these authors Palladini gives us the most adroit description of the symbols usage:

The reader should be aware that I want you, having drawn your sword from its scabbard at some distance from your enemy, to move to meet him gallantly and with heart, as such endeavours demand. Having advanced to within two or three steps of him, remaining sufficiently covered against any attack he might attempt, you can then exercise judgement to determine the spot where you may attack. You should approach until you see that by extending your arm and stepping with your right foot you may wound him, either with the point or the cut, depending on the opportunity and situation.

This is termed the misura di fierire, and you must practise this measure many times in order to seize it when needed, since you cannot use a compass against your enemies in disputes. Neither do any deride this method, since it is the only means of attacking securely, which you will see through practice. If however you do not observe this method, you risk a response from your enemies sword.

—Camillo Palladini {Terminello, pg. 63}

It's possible that the symbol or segno is a device that was inherited from Filippo Dardi. Alas, whatever echo’s of Dardi’s legacy that made it into the tradition will always remain a mystery until his treatise is discovered—if it still exists—and any factual reasoning beyond that will continue to be built on speculation.

However, it’s my hope that the debate around Dardi's incorporation in the Bentivoglio tradition of fencing; ie.) Achillini, Marozzo, Manciolino, the Anonimo Bolognese, Viggiani, dall’Agocchie, Ghisiliero, and Cavalcabo to name a few, can be put to bed, or at least take on a new narrative focus; as all of the families of these authors can be directly linked to the Bentivoglio faction in Bologna, or in some form or another can be linked directly to known authors in the tradition. Now that Dardi’s role in Bentivoglio faction has been made more clear by this article, I hope we can happily re-enshrine him as a forefather—taproot—or a pillar of this vibrant and exceptional fencing tree that touched not just the lives of the Bolognese citizens and Bentivogleschi partisans, but provided intrigue and insight to emperors, popes, kings, dukes, and esteemed warriors across the European continent.

Works Cited:

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacchi Volume III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Of the History of Bologna. Volume 2. Italy, Giovanni Rossi, 1657Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Della Historia Di Bologna. Volume 2. Italy, Giovanni Rossi, 1657

Uknown. The Studium flourishes: The history of the University of Bologna in the 15th century. Unibo.it. https://www.unibo.it/en/university/who-we-are/our-history/nine-centuries-of-history/the-studium-flourishes. Accessed 02/29/2024.

Stokes, Brian. Lippo Dardi: Dardi Letter Translation. 2015. Link to Archive.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937.

Muzzi, Salvatore. Annali della città di Bologna: dalla sua origine al 1796. Italy, Tipi Di S. Tommaso D'Aquino, 1842.

Tamba, Giorgio. MARESCOTTI DE’ CALVI, Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/marescotti-de-calvi-ludovico_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 03/01/2024.

Gelli, Jacopo; Nedo, Nadi. SCHERMA (fr. escrime; sp. esgrima; ted. Fechten; ingl. fencing); Enciclopedia Italiana (1936). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/scherma_(Enciclopedia-Italiana)/. Accessed. 03/05/2024.

Tamba, Giorgio. GOZZADINI, Tommaso; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 58 (2002). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/tommaso-gozzadini_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 02/28/2024.

Chidester, Michael. Filippo Dardi. Wiktenauer.com. https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Filippo_Dardi#cite_note-Rubboli-1. Updated 11/7/2023. Accessed 03/05/2024.

Tamba, Giorgio. FOSCARARI (Foscherari), Raffaello; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 49 (1997). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/raffaello-foscarari_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 03/05/2024.

Tamba, Giorgio. MALVEZZI, Gaspare; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 68 (2007). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/gaspare-malvezzi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 03/01/2024.

Strnad, Alfred A. CACCIALUPI (Cazalupis, Cazalupus, Cazalove, Chazalove), Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 15 (1972). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/ludovico-caccialupi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 03/01/2024.

Leoni, Tom. The Complete Renaissance Swordsman: Antonio Manciolino's Opera Nova (1531). United States, Freelance Academy Press, 2010.

Leoni, Tom. Achille Marozzo; Opera Nova, Book 1: Sword and Buckler. United States, Lulu Press, April 2018.

Terminiello, Piermarco and Pendragon, Joshua. The Art of Fencing; The Forgotten Discourse of Camillo Palladini. United Kingdom, Royal Armouries Museum, October 2019.

Marescotti, Galeazzo. Cronaca di Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi. Poemetto latino di Tommaso Seneca e versi di Tribraco Modenese. Inventario dei manoscritti della biblioteca Comunale dell'Archiginnasio di Bologna (serie B), a cura di Lodovico Barbieri, III, Firenze-Roma, Leo S. Olschki, 1945 (Inventari dei manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia, a cura di Albano Sorbelli, LXXV), p. 112-113. https://www.originebologna.com/luoghi-famiglie-persone-avvenimenti/avvenimenti/racconto-di-galeazzo-marescotti-sulla-liberazione-di-annibale-bentivoglio-dalla-prigionia-di-varano-sulla-uccisione-dello-stesso-annibale-e-dei-fatti-che-ne-seguirono//. Accessed 03/06/2024

Mazzetti, Serafino. Repertorio di tutti i professori antichi, e moderni, della famosa università, e del celebre istituto delle scienze di Bologna: con in fine Alcune aggiunte e correzioni alle opere dell'Alidosi, del Cavazza, del Sarti, del Fantuzzi, e del Tiraboschi. Italy, Tip. di S. Tommaso d'Aquino, 1847. pg. 110 LINK

Correlati, Lemmi. CAPPONI, Neri; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 19 (1976). Treccani.it. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/neri-capponi_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. Accessed 03/07/2024.

Chidester, Michael. Filippo Dardi. Wiktenauer.com.

In 1434, he seems to have written a treatise on fencing and geometry…

Gelli, Jacopo; Nedo, Nadi. SCHERMA (fr. escrime; sp. esgrima; ted. Fechten; ingl. fencing); Enciclopedia Italiana (1936). Treccani.it.

Guido Antonio di Luca, come il Dardi suo maestro, fu protetto dai Bentivoglio, i quali ne frequentarono la scuola di via Saragozza a Bologna, ov'egli abitò sino alla sua morte.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 88

Alli 4 di maggio , il mercoledì , i l senato celebra la festa di santa Monica nella chiesa de ' frati di San Jacomo et un vescovo spagnuolo vi canta la messa , dove furono molti genti lhuomini segnalati , cioè : …Simone Manfredi…

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 89

Si ottenne il partito et 40 si elessero ancora alcuni huomini amatori della repubblica , a ' quali si diede autorità di far quanto in detto conseglio era ottenuto . Gli eletti furono questi, cioè : Giovanni d i Nicolò di Ligo cavaliere , Bornio di Beltrame da Sala famosissimo dottore, Jacomo di Giovanni da Mo glio , Melchior di Nano da Viggiano , Cristophoro di Braiguerra Caccianemici , Giovanni di Tomaso Bianchetti , Tomaso di Giovanni Zanetini, Cantaglino di Jacomo da Saliceto , Giovanni Bartolomeo Guidotti , Lodovico Caccialupi , Simone di Giovanni Manfredi…

Tamba, Giorgio. GOZZADINI, Tommaso; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 58 (2002). Treccani.it.

Alla società con i fratelli Sacrato di Ferrara il G. aveva infatti affiancato dal dicembre 1440 un'altra società in Bologna che lo vedeva socio di Nicolò Sanuti, Simone Manfredi e Virgilio Malvezzi e nella quale il G. aveva conferito un capitale di 1500 lire. Anche in questo caso si trattò di un ottimo investimento, dal momento che, dopo un solo anno di attività, il guadagno complessivo della società si avvicinava a 3000 lire. Il capitale che il G. vi aveva conferito, forse a motivo dell'incarico pubblico che egli rivestiva, fu peraltro denunciato a nome del cugino Venceslao, figlio di Bonifacio.

Tamba, Giorgio. FOSCARARI (Foscherari), Raffaello; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 49 (1997). Treccani.it.

Il 22 maggio furono nominati i nuovi membri degli organi di governo e il F. assunse la carica di gonfaloniere di Giustizia.

Tamba, Giorgio. FOSCARARI (Foscherari), Raffaello; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 49 (1997). Treccani.it.

Al tempo stesso si assicurò il controllo delle entrate del Comune, facendosi nominare, con un decreto adottato dal Collegio degli anziani il 30 ag. 1438, tesoriere generale per un quinquennio, un periodo del tutto eccezionale.

Tamba, Giorgio. FOSCARARI (Foscherari), Raffaello; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 49 (1997). Treccani.it.

Egli prese quindi a sollecitare con insistenza Annibale Bentivoglio affinché rientrasse in città.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Pg. 19

Foscherari replied by threatening to send him back to groom horses as a soldeir of fortune, and Annibale began to lay his plans for sweeping his enemy from his path. (Filino della Tuata, Storia universale, ii, f. 25; Poggio Annali, f. 466; corpus, vol. iv, p. 98.)

Tamba, Giorgio. MALVEZZI, Gaspare; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 68 (2007). Treccani.it.

Questi nel 1440, formalmente al comando di milizie del Visconti, dette vita, d'intesa con l'oligarchia cittadina, a un suo tentativo di insignorirsi di Bologna. L'affidamento della Tesoreria comunale a una società di privati, esponenti delle maggiori famiglie, assicurò a queste la tutela dei propri privilegi e un'ampia indipendenza dal potere politico; il Piccinino ottenne in cambio un credito pressoché illimitato sulle finanze del Comune. In questo complesso accordo il M. ebbe parte. Fu del ripristinato Collegio dei Sedici riformatori che nel marzo 1440 deliberarono l'affidamento della Tesoreria e a novembre andò con Giovanni da Manzolino a Parma, ambasciatore al Piccinino, siglando i patti che, ponendo Bologna sotto la protezione del capitano, ottenevano per la città una larga autonomia dal Visconti e al Piccinino assicurarono il soldo per le sue milizie.

Tamba, Giorgio. GOZZADINI, Tommaso; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 58 (2002). Treccani.it.

Alla morte di Foscarari fecero seguito la cassazione dei privilegi accordati ai suoi eredi, un nuovo accordo con Piccinino, che garantiva al capitano di ventura il denaro necessario a pagare le sue truppe e l'aspirazione a crearsi una propria signoria, e soprattutto un nuovo sistema di gestione della Tesoreria bolognese. A tale scopo una società di privati mutuò alla Tesoreria la somma di 12.000 lire di bolognini necessaria a coprire le esigenze di Piccinino e ne ricevette in cambio la gestione della stessa Tesoreria e una provvigione, quale compenso per tale gestione, pari al 66% della somma mutuata. L'elenco dei sottoscrittori del prestito, che formavano nel contempo il Consiglio di Tesoreria, comprendeva nomi delle più prestigiose famiglie della città: Albergati, Bolognini, Fantuzzi, Malvezzi, Zambeccari. Tramite il Consiglio di Tesoreria l'oligarchia cittadina si era così assicurata la gestione delle finanze della città e con essa anche la propria sopravvivenza come classe di governo locale.

Strnad, Alfred A. CACCIALUPI (Cazalupis, Cazalupus, Cazalove, Chazalove), Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 15 (1972). Treccani.it.

Partigiano di Annibale Bentivoglio, per desiderio del quale partecipò tra l'altro all'assassinio del ricco gonfaloniere di Giustizia Raffaele Foscherari, avvenuto il 6 febbr. 1440

Strnad, Alfred A. CACCIALUPI (Cazalupis, Cazalupus, Cazalove, Chazalove), Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 15 (1972). Treccani.it.

Discendente da una nobile famiglia originaria di Fano stabilitasi a Bologna, il C. nacque in questa città poco dopo il 1400 da Antonio. Intraprese la carriera notarile e come notaio è ricordato nel 1438, quando fu eletto tra gli Anziani di Bologna per porta Ravegnana.

Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Of the History of Bologna. Volume 2. Italy, Giovanni Rossi, 1657Ghirardacci, Cherubino. Della Historia Di Bologna. Volume 2. Italy, Giovanni Rossi, 1657

La Tribu di Porta Ravegnana, doveva ragunarsi fuori della Citta a San Gregorio sotto l'insegna del Capitan Guido da Manzolino. La Tribu di Porta Stieri

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 11

Poi alli 4 d'agosto fecero sedeci riformatori dello stato della libertà , cioè : Guido Pepoli , Romeo Foscarari , Bartolomeo Mangioli , Braiguerra Caccianemici , Nicolò Ariosti , Scipione Gozzadini , Baldessera Canetoli , Tomaso di Carlo Zamb eccari , Stephano Ghisilardi notaro , Francesco Guidotti , Giovanni Griffoni , Giovanni da Manzolino notaro…

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 40

Nicolò Piccinino seguita vittoria et assedia Granarolo . Alli 17 d'ottobre , la domenica , due ambasciatori bolognesi vanno a Fiorenza al papa a condolersi de ' suoi travagli et anco per cercare accordo con esso lui ; gli ambasciatori furono Romio da Sala dottore et Giovanni Manzolino notaro.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 65

1440 , 17 novembre . Capitoli et patti con l'illustrissimo capitano Nicolò Piccinino. Furono fatti in questo tempo alcuni capitoli et conventioni et confirmati fra Nicolò Piccinino Visconte , marchese et conte ducale , luogotenente et capitano generale et governa 15 tore del popolo di Bologna , suo contado , diocese , forze et distretto per una parte et Gasparo Malvezzi et Giovanni da Manzolino oratori et procuratori della città et commune di Bologna.

Strnad, Alfred A. CACCIALUPI (Cazalupis, Cazalupus, Cazalove, Chazalove), Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 15 (1972). Treccani.it.

(R)aggiunse presto dignità e onori nel Comune bolognese: il 14 giugno 1443 fu eletto a far parte degli Otto dell'avere e il suo nome compare anche tra quelli dei cittadini incaricati di attuare i provvedimenti fiscali deliberati nel Consiglio dei seicento.

Stokes, Brian. Lippo Dardi: Dardi Letter Translation. 2015.

We saw and gave mature consideration to this report, and gladly acceding to your reasonable requests, by the authority of our magistracy, in every way, law and form in which it can be done, by our present decree we have decided and undertaken to ensure and we desire and order that everything contained in the above report be observed for you, expressly enjoining each and every person to whom it concerns or may concern in the future that our present decree is to be observed and they are to ensure that it is inviolably observed, on pain of our displeasure. Bologna, 24 Dec. 1443

Strnad, Alfred A. CACCIALUPI (Cazalupis, Cazalupus, Cazalove, Chazalove), Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 15 (1972). Treccani.it.

Poco dopo si recò a Firenze, insieme con Azzo da Quarto, per convincere il figlio bastardo di Ercole Bentivoglio, Sante, che in questa città apprendeva l'arte della lana, ad assumere la guida della fazione bentivogliesca, come tutore del giovane Giovanni, figlio ancora minorenne di Annibale Bentivoglio, assassinato nel giugno del 1445 da Bettozzo Canetoli.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Pg. 33

He returned to Poppi to his reputed uncle Antonio da Cascese, on whom, owing to the death of his mother and foster-father, he depended for his start in life. Antonio was a comparatively rich man, and he apprenticed Sante to Nuccio Solosmei, a wool-merchant of the parish of San Martino in Florence, paying down three hundred florins on his behalf and commending him to the care of his friend Neri Capponi.

Correlati, Lemmi. CAPPONI, Neri; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 19 (1976). Treccani.it.

Il contributo del C. alla politica fiorentina si realizzò in modo particolare nel settore degli affari esteri, e specialmente in quello della supervisione e della direzione della politica militare. La fondamentale importanza della guerra nella vita politica, e la conseguente necessità di stabilire buone relazioni con i più importanti condottieri, erano già state sostenute dal padre del C., Gino, nel corso della sua attività pubblica e dallo stesso teorizzate nei Ricordi, scritti nell'ultimo anno di vita a guisa di consigli per i propri figli.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Pg. 33.

According to Neri’s own account he was himself unaware of Sante’s origin until after Annibale’s death, when ‘a Bolognese called Ser Cola’ arrived in Florence bearing the credentials from the Sedici, and told him of the desire of the Bentivogleschi for Sante’s return.

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Pg. 42.

Within a year of Francesco Sforza’s accession as Duke of Milan, Sante had established himself in his confidence. In 1451 Francesco Sforza was writing to Sante as to a trusted friend, and treating him as his confidential agent in his dealings with the lords of the Romagna. Galeazzo Marescotti, who had seen service under Francesco Sforza, realized that Sante had supplanted him in the ducal favour: “Your illustrious lordship has placed his throughts and hopes here in others than myself”, he wrote in December 1451. The intimate relations between them lasted as long as a Sforza ruled in Milan or a Bentivoglio in Bologna.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 81

Annibale andò a casa di Ludovico Marescotto a salutarlo , et anche per conferir seco di quan to si haveva a fare per liberare la città dalla tirannia di Francesco Piccinino . Ludovico, vedendo Annibale , egli et li figliuoli insieme con incredibile allegrezza corsero ad abbracciarlo , rallegrandosi seco della sua liberatione , et tosto quivi concorsero gli amici per vederlo , et fra gl'altri Melchiorre Viggiani , huomo di molta stima nella città et uno de gl'antiani , il quale verso Annibale dimostrò gran segno di vero amore , et parimente fecero il simile gli amici de 'Canetoli , ciascuno proferendosi ad Annibale pronto al porre la vita et per lui et per la libertà della patria . Volle Ludovico Marescotto , et così parve a Ludovico dalle Coreggie et a tutti gl'altri cittadini principali , che Annibale senza punto tardare andasse a casa s ua in strà San Do nato , et che quanto prima facesse dare il segno alla campana de ' frati di San Jacomo per ra dunare il popolo et subito passare alla piazza gridando : " Viva il popolo et l'arti.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 80

Volle Ludovico Marescotto , et così parve a Ludovico dalle Coreggie et a tutti gl'altri cittadini principali , che Annibale senza punto tardare andasse a casa s ua in strà San Do nato , et che quanto prima facesse dare il segno alla campana de ' frati di San Jacomo per ra dunare il popolo et subito passare alla piazza gridando : "Viva il popolo et l'arti ,. Furono fra tanto avisati Romeo Pepoli , Virgilio Ma lvezzi et altri assai della venuta di Annibale , li quali con ogni maggior prestezza che si puotè radunarono gli amici loro et presero l'arme . Parimente Annibale havendo radunato gli suoi et posto a ordine il tutto , fece che il padre di Giovanni Sabbadin o degl'Argenti con l'aiuto d'altri suoi amici pigliassero la porta di strà San Donato per havere egli l'entrata et l'uscita della città libera , se bisognasse . Poi 45 fece dare alla campana di San Jacomo circa alle 4 hore , et il popolo pigliando l'armi e t correndo alla piazza della casa di Annibale , trovarono con loro gran contento Annibale che passava alla piazza gridando: " Viva il popolo et l'arti ,, et lo seguitarono .

Marescotti, Galeazzo. Cronaca di Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi. Poemetto latino di Tommaso Seneca e versi di Tribraco Modenese. Inventario dei manoscritti della biblioteca Comunale dell'Archiginnasio di Bologna (serie B), a cura di Lodovico Barbieri, III, Firenze-Roma, Leo S. Olschki, 1945 (Inventari dei manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia, a cura di Albano Sorbelli, LXXV), p. 112-113.

Secondo ne riferì la fama. e gli strenui miei tre fratelli, che sempre seguirono il magnifico Annibale, si diportò questi con tal valore da ottenerne gloria imperitura, essendo opinione in tutti invalsa che egli per la . sua virtù e gagliardia fosse principal causa che il conte Alvisi ed altri signori condottieri o valentissimi uomini fossero rotti e fugati siccome avvenne. La mischia durò dalle ore prime del mattino fino ad ora tarda, e la rotta toccata all‘inimico fu si completa da non ricordarsi negli annali della nostra storia, imperocchè tutti i carri e uomini di seguito furon presi, molti essendo morti per la sete come pure un numero sterminato di cavalli, perché dove ebbe luogo l‘assalto non eravi nè fiume, nè fonti, né pozzi, ed il caldo oltremodo molesto essendo alla metà di agosto.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 82

Dentro l'argine poi vi erano le habitationi delli soldati et nel mezzo un torrione alquanto più alto di tutta la fabrica . Eravi poi per presidio Tartaro , huomo nel l'armi molto esperto et al duca et al Piccinino veramente fedele . Q uesti adunque non vo lendo consignare il detto castello , il senato diede la cura per riacquistarlo ad Annibale Ben tivogli et a Galeazzo Marescotti , li quali passarono con li soldati al mercato de ' buoi ( così no minavasi quella piazza quadrata di cui sopra è detto ) et cominciarono ad assediare il detto castello con bombarde et altre machine da combattere .

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Pg. 27.

This was held by one of Piccinino’s captains with two hundred men (Note: Ghirardacci and Marescotti say 400-500), and Annibale’s plan was to dig a deep trench between the city and fortress to impede sorties from the garrison. Doctors and students of the University, trade gilds under their banners, members of the religious orders, knights, peasants, Jews, all lent a hand with the work until the trench was finished.

Marescotti, Galeazzo. Cronaca di Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi. Poemetto latino di Tommaso Seneca e versi di Tribraco Modenese. Inventario dei manoscritti della biblioteca Comunale dell'Archiginnasio di Bologna (serie B), a cura di Lodovico Barbieri, III, Firenze-Roma, Leo S. Olschki, 1945 (Inventari dei manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia, a cura di Albano Sorbelli, LXXV), p. 112-113.

A sussidiarne videsi, come vero padre della patria, fra molti dottori e rispettabili cittadini, il vero lume di sapienza, messer Giovanni d‘ Anania dottore antico e celebratissimoin utroque, che non vergognava, deposto il proprio mantello, di prendere la zappa, ed in compagnia degli altri porgere il suo senile braccio alla pietosa e necessaria opera. Vi vennero pure molti venerandi frati maestri in teologia, così cittadini come forestieri, e tutti i preti e frati vi concorsero pure.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 83

Et vi anda rono tutti li cittadini , etiamdio li dottori , fra ' quali vi fu Giovanni di Annania celeberrimo dottore in questi tempi , il quale , deposta la toga dottorale , si era vestito d'armi , et molto si travagliò nel fabricare gl'argini intorno la fortezza .

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 87

20 di giugno , il gio vedì , che fu la festa di san Raphaele , la notte , il signor Astorre di Faenza capitano di Nicolò Piccinino entra in Bologna con 400 cavalli per la porta che era presso il castello, che si stava spalancata giorno et notte per esser guasta la porta di leg no ( o simplicità o più tosto negligenza degl'huomini di questi tempi ! ) , et fuori era il conte Luigi con l'essercito.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 87

Il senato, accortosi di questa entrata , tosto fa dare il segno alle campane , 35 et il popolo piglia l'arme et passano circa 9000 pe rsone fra cittadini , soldati stipendiati et popolari al mercato , et quivi si fa una sanguinosa scarramuzza ; et avenga che il castello con le bombarde aiutasse Astorre, nondimeno i Bolognesi lo cacciarono fuori della città con la morte di molti de ' suo i et con sua gran vergogna .

Marescotti, Galeazzo. Cronaca di Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi. Poemetto latino di Tommaso Seneca e versi di Tribraco Modenese. Inventario dei manoscritti della biblioteca Comunale dell'Archiginnasio di Bologna (serie B), a cura di Lodovico Barbieri, III, Firenze-Roma, Leo S. Olschki, 1945 (Inventari dei manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia, a cura di Albano Sorbelli, LXXV), p. 112-113.

(P)erchè dal canto nostro non eravamo molto forti di forestieri, avendo al nostro soldo soltanto per capitano quel valoroso e fedelissimo uomo Piero di Navarino con cavalli 400 e 300 fanti appena. Avevamo ancora in nostro aiuto Simonetto con cavalli 300 speditoci dai signori Fiorentini, e Tiberto Brandolino con cavalli 400, il quale per le lodevoli e degne opere sue da non molto militando in Lombardia per la Illustrissima Signoria di Venezia, questa lo mandò in nostro aiuto, diportandosi ver noi in modo, che ne venne sì celebre e valente, da esser fatto poi capitano,e cavaliere per un incontro glorioso avuto sotto le porte di Milano. In progresso di tempo acquistò solennissima fama, e fu chiamato messer Tiberto Brandolino.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 89

Vengono nuove al senato che li Venetiani mandono a ' Bolognesi Tiberto Brandolino con 450 cavalli et Guido Rangoni con 600 et 200 fanti. Mentre che ne vengono le sudette genti de 'Venetiani in soccorso della città , li cittadini non mancano di travagliare il castello con le bombarde et saette et schioppi , et il simile anche fanno gli presidi della fortelezza contro la città ; ma come avenne , li nostri alla fine get tarono per terra da 6 pertiche di muro Simonetto alli 16 di luglio.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 88

I Fiorentini mandano a ' Bolognesi Simonetto da Castel San Piero dell'Aquila con Gottifredo et ottocento cavalli bene a ordine et 800 fanti , li quali alli 6 di luglio , il sabbato , entrano in Bologna. Li cavalli andarono ad alloggiare fuori di str à San Stephano , li pedoni nel mer cato et il capitano Simonetto nelle Lame , dove li signori antiani honoratamente il trattarono et gli fecero un bellissimo presente.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 82

Era Lodovico dal Verme a Castello San Piero con 4000 cavalli et due mila fanti per passare a Nicolò Piccinino nella Toscana , che era contro il conte Francesco da Cudignola , et perciò gli antiani dubitavano che egl i , intendendo la ribellione della città , non tornasse addietro et per la porta del castello di Galliera , che era per anco a sua divotione , non entrasse alla città et la sacchegiasse .

Marescotti, Galeazzo. Cronaca di Galeazzo Marescotti de' Calvi. Poemetto latino di Tommaso Seneca e versi di Tribraco Modenese. Inventario dei manoscritti della biblioteca Comunale dell'Archiginnasio di Bologna (serie B), a cura di Lodovico Barbieri, III, Firenze-Roma, Leo S. Olschki, 1945 (Inventari dei manoscritti delle Biblioteche d'Italia, a cura di Albano Sorbelli, LXXV), p. 112-113.

(I)l conte Alvisi trovarsi sul territorio bolognese con 4000 cavalli e 2000 fanti

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 93.

Ne resta rono prigioni di quei di riputazione 236 , fra ' quali vi erano questi : Peterlino fratello del conte , il figliolo del conte di Poppi con undeci capi di squadre , due mila cavalli, con tutti li ca riaggi et bagaglie .

Ady, Cecilia Mary. The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1937. Pg. 27.

At the end of two months the castellan agreed to hand over the fortress to the citizens in return for 35,000 ducats.

Stokes, Brian. Lippo Dardi: Dardi Letter Translation. 2015.

(A)nd that my account books should be given probative value against any youth younger than twenty-five and against anyone still in their fathers’ custody, and likewise against anyone who were # [sic] surety on account of the said plays, according to the records of my school [stating] which youths had started or finished or not finished.

Uknown. The Studium flourishes: The history of the University of Bologna in the 15th century. Unibo.it.

The professors became public employees, paid with income from the Gabella Grossa (tax on goods). This inevitably led, on the one hand, to the subjugation of professorships and degree programmes and, on the other hand, to foreign teachers being sent away who, in previous seasons, had enriched the quality of the teaching.

Mazzetti, Serafino. Repertorio di tutti i professori antichi, e moderni, della famosa università, e del celebre istituto delle scienze di Bologna: con in fine Alcune aggiunte e correzioni alle opere dell'Alidosi, del Cavazza, del Sarti, del Fantuzzi, e del Tiraboschi. Italy, Tip. di S. Tommaso d'Aquino, 1847. Pg. 110.

lo.'io. 1)A1U)I Lippo, o Filippo fi* f;lio di linrtolomeo lIolof^naBe. Fa Lat^ torli di Aritm^tim, t* <»AOirietria 4all'anno i44'' V^' tutto il i463. Nel* l*anno t444 If'tx*^ anidia PAHtronomii* Krra l'Alido^ti a fui lo Lettore •oltaV' to Mino h\ ì^hì , mentre trovati in* Hrrirto nuMluoli aiiclie de' duo anni fie^uiMiti 14^'^ e l4^•^• Riteniamo inoltre fìlin lo AteNMO Alidoti sbagli n«l darci tra i Dottori Forentieri un LippO Durili Hpaf^nuoio Lettore di Aritmetica f UftttfìiiU'ìii dui 1444 *l i4-^'^t poiché no* detti Ruoli non eniite elio il in^* di*tto Dardi liologneue , eii il eogno» me iitteMo ri fa certi di aver eiM duplicato quanto iiop;|^etLo, rome fata di purecclii altri «dio a tuo luogo tn* di'remo notando. = Alidoti Dottori in Arti Holopunti p. /Ì7, e Forettiari p.So.

Carducci, Giosuè, et al. Rerum italicarum scriptores: raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento; Ghirardacci Book III. Italy, S. Lapi, 1929. pg. 87

Bernardino Gozzadini . Questi furono gl'o tto dell 'havere : Giovanni di Tomaso Bianchetti , Bonifacio di Turzo Fantuzzo , Francesco di Jacomo Ghisilieri , Battista di Ludo vico Ramodini, Lodovico Caccialupi notaro , Urbano di Guglielmo dalla Fava, Facino di Flo 15 rio dalla Nave, Crescentio di Bartolomeo dal Poggio.

Tamba, Giorgio. MARESCOTTI DE’ CALVI, Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). Treccani.it.

Nel dicembre 1413 fu coinvolto in una congiura contro il governo pontificio promossa da alcuni dottori dello Studio, che confidavano nell’intervento di Gian Galeazzo Manfredi, signore di Faenza. Ai congiurati il M. assicurò il suo appoggio e la fornitura di armi, che in effetti sembra fosse in grado di procurare. Il complotto fu scoperto e il suo principale promotore, Gregorio Gori, giustiziato. Gli altri congiurati e il M., fuggiti, furono condannati a morte in contumacia.

Tamba, Giorgio. MARESCOTTI DE’ CALVI, Ludovico; Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani - Volume 70 (2008). Treccani.it.

Mentre Anziani e Riformatori inviavano ambasciatori al Visconti per chiedere la loro liberazione, il M. e altri bentivoleschi assoldavano milizie a presidio dei palazzi pubblici.