On a warm afternoon in the late spring of 1508, a marked man marked rode his mule quietly through the city gates of Ferrara, eager to escape the oppressive city air for the cooling winds of the open countryside. His name was Hercules Strozzi—a poet whose verses were matched only by his dangerous service as the secret intermediary for two lovers bound not only by noble blood but by forbidden passion: the Marquis of Mantua and the Duchess of Ferrara.

Yet Strozzi's perilous loyalty on behalf of forbidden love was no secret to the powerful brothers who ruled Ferrara: the Duke and his brother, the formidable Cardinal d'Este.

As Strozzi guided his mule down quiet country paths, a band of ruthless men ambushed him without mercy. Strozzi, crippled and dependent on a cane, had no chance against these savage killers. The attackers left his body cruelly torn open, pierced by no fewer than twenty-two wounds. Under cover of darkness, they dragged his lifeless form back into Ferrara, abandoning him in an alley frequented by drunks, where his mutilated body was discovered at dawn.

The murder unleashed a scandal that swept through Ferrara. While not beloved by all, Hercules Strozzi had been a confidant of the Duchess herself, and his murder was a public affront. Hercules was also a first cousin to Guido Rangoni, who no doubt felt fury over the murder. [1] Suspicion soon fell upon the ruling d’Este family, and when the Duke deliberately refused to pursue justice, there remained little doubt about who had ordered the poet be turned into food for the worms.

Guido Rangoni’s anguish only deepened when he uncovered a devastating betrayal—Alexander Pio, his own cousin and childhood companion, had orchestrated the murder plot under the Bentivoglio family’s auspices.[2] This dark act forged an alliance between the Bentivoglio and the Lords of Ferrara.

Yet in the Italy of the Renaissance, dishonor saved more men than did a sharp sword.

And in July 1508, the sinister alliance between Ferrara and Bentivoglio became Guido Rangoni's lifeline. The tide had turned cruelly against Guido and the Bentivoglio brothers. Cardinal Alidosi had ruthlessly crushed their hopes by executing Mancino da Bologna along with scores of their supporters. Their dreams of reclaiming Bologna were extinguished; mere survival was now their only focus. Guido, bearing a price of 4,000 ducats on his head, was hunted relentlessly by men eager to claim the Pope’s bounty.

In his hour of greatest desperation, Guido fled to Ferrara, sheltering under the tenuous protection provided by the Bentivoglio's uneasy pact with the Duke. But this sanctuary was fleeting.

In November, Pope Julius uncovered Guido’s hiding place. In swift retaliation, he imposed an interdict upon Ferrara—a devastating spiritual sanction akin to excommunicating an entire country. Churches closed their doors; sacraments ceased, plunging Ferrara into spiritual turmoil. Pressured by his people, the Duke had no choice but to expel Guido Rangoni.

With nowhere left to run, Guido faced his darkest moment. Just then, in his desperate hour, Venice offered him sanctuary—but at a price. The Republic, on the brink of its own existential crisis, needed seasoned soldiers. Guido Rangoni had no choice but to accept their refuge and take up arms on behalf of the Most Serene Republic of Venice.

The League of Cambrai

So far the story of Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli has focused on their families and on the struggle to either remain in or regain control of Bologna. But now a great maelstrom was descending on Italy, and their lives would not only become caught up in this storm, but would be forever changed by it.

In late 1508 the main powers of Europe, France, the Empire, Spain, Venice, Rome and others, were all meeting in the town of Cambrai. Ostensibly, they were seeking to mediate disputes that many had with Venice, but the real purpose of the tete-a-tete was to divide Venetian territories between them and develop an alliance to take Venice’s territories. The deals they made would plunge Italy into nonstop war for the better part of a decade.

The Republic of Venice’s empire included most of northeastern Italy. The Venetians had a well-deserved reputation as great merchants – the city of Venice itself was probably the wealthiest square mile on Earth at the time. Unfortunately for Venice they had hungry neighbors on their border: the Holy Roman Empire to the north, the French to their west, and the Papal States to the south.

There was a general belief that the Venetians were not much use in war. As the King of France said to the Venetian ambassador in 1499, “You Venetians are wise in your deliberations…but lack the courage to fight – you have too much fear of death!” In 1508 the German Emperor decided to take on Venice by himself. He sent an army to invade Venetian territory. The Venetians under their commander Bartholomew d’Alviano cut down the German knights and infantry like so much summer wheat.1 This was the same d’Alviano that the Bentivoglio had defeated on behalf of Florence in our episode, “Hired Swords.”

In Cambrai, the French wove together an alliance against Venice that eventually included almost every other power of note in Europe. Though Venetian envoys were present in Cambrai, they became aware that much of the business being transacted was being done without them. Venetian intelligence was the finest in Europe and they more or less deduced what was being discussed.

In the preamble to the treaty that formalized the League of Cambrai, Emperor Maximiliam summed up the League’s mission as they saw it. “…stop the losses, the abuses, the robberies, the harms which the Venetians have caused not only to the Holy Apostolic See, but also to the Holy Roman Empire, to the House of Austria, to the Dukes of Milan, to the Kings of Naples and to many others principles occupying and usurping tyrannically their goods, their lands, their cities and their castles, as if they had conspired to the ill of everyone [...] So we found not only useful and honorable, but also necessary to call everyone to a right revenge to turn off, like a common fire, the Venetians' insatiable greed and their thirst for domination.”2

The Plan of Defense

In the spring of 1509, the drums of war echoed ominously across Italy as armies set out for war. From the northeast, the Holy Roman Empire’s forces lumbered slowly into motion. Though numerous, they represented a patchwork nation of conflicting loyalties and sluggish resolve—an army burdened by a medieval inertia. Venice viewed their advance with cautious disdain, confident that this enemy posed no immediate threat.

Far more immediate, however, was the army marching from the south under the crossed keys of the Pope’s banners. Though commanded by the Pope’s nineteen-year-old nephew, the Duke of Urbino, this smaller force nonetheless moved swiftly, staffed by disciplined, professional soldiers. Yet the Venetians, with numerical superiority felt assured they could decisively defeat this papal threat—if they chose to confront it.

But the true danger, stark and undeniable, lay in the formidable armies of France. France was a modern nation equipped with disciplined, battle-hardened professionals. To have even the slightest hope of withstanding the French, Venice had no choice but to commit nearly all of its strength to meet them.

Thus Venice faced a perilous dilemma. Concentrating their troops against France meant leaving their vital southern flank dangerously vulnerable, especially around Faenza, the region critical for supplying Venice with experienced infantry. Yet diverting resources southward risked catastrophe against the overwhelming French attack.

It was amidst this strategic crisis that two emissaries from Bologna arrived, bearing a proposal that could alter Venice’s fate. Representing Hannibal Bentivoglio, they assured Venice’s ruling council that the Bentivoglio cause still burned fiercely within Bologna’s walls. With Venetian financial backing, they promised, an army could swiftly be assembled to retake Bologna, offering Venice a way out of its strategic deadlock.

While this would anger the Pope, any danger to Bologna would keep the army of the Pope busy, would give Venice valuable time to defeat the French army and then deal with the army from Rome.

In Venetian Service

After a long debate, that “went past vespers,” the Venetians threw their support behind the Bentivoglio.

The Republic of Venice took on the Bentivoglio as condottieri and allotted them funds for a force of 150 men-at-arms, 200 light cavalry and 3000 infantry to use in retaking Bologna. Naturally, Guido Rangoni was right there with them.

With Hannibal involved in obtaining money for the whole force and in working with Venetian officials, it fell to Guido Rangoni to help his uncle inspect the recruits and organize the company of men-at-arms. The army would make its base near the coastal town of Ravenna, about forty miles (65km) from the gates of Bologna.

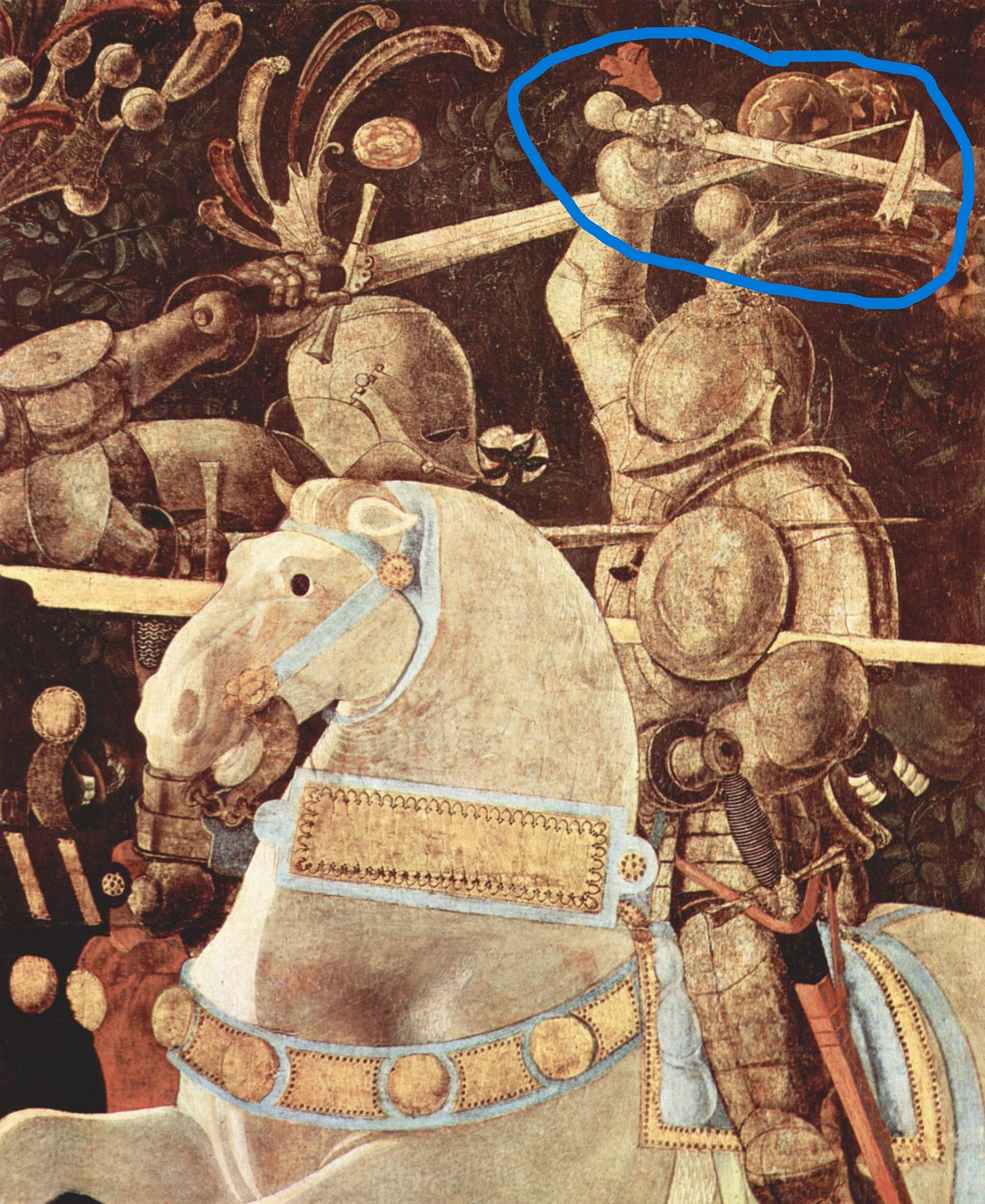

In the Italian system of organization a company of men-at-arms was divided into lances, a unit consisting of the knight himself (a man at arms being a professional knight), a squire who also doubled as a light cavalrymen in battle, and a groom who was a non-combatant.[10] The main weapon of the mounted man-at-arms was the lance, a weapon that could strike with such force that it could knock a man off his horse and send him flying like a missile into his fellows behind him. That was if you wanted to attack the rider. Monte advises differently, “With the encounter of the spear it is an easy thing to kill horses, whether in massed combat or one-on-one. We should be most attentive to do this if we are keen to win. Fools aim their blows at the rider and not the horse.”[1]

We are fortunate that one of the greatest men-at-arms of the era, Pietro Monte, also wrote extensively on the weapons being used at the time. Once the mounted warriors no longer had the opportunity to charge with a lance the battle became a fight with warhammers, a smaller cousin of the pole-axe. These could be used in one hand, so that the other hand could control the reins, but in the game of hammer on hammer, “Holding the shaft or warhammer with both hands is much stronger than with just one, since one hand cannot adequately resist two.”[2]

The warhammer was a weapon that fully utilized a man’s strength so that he could injure an opponent encased in steel. But it was not the primary weapon. “When men-at-arms are armed with white and heavy arms and fight on horseback, above all other weapons they use estocs.”[3] With a weapon like this, a man on a strong horse would seek to push the opponent’s horse aside and then drive the point of the estoc into vulnerable areas on the body like the throat or the armpit.

That was if you chose to attack the rider, even with the estoc Monte still advised attacking the enemy’s horse whenever possible, especially if they were riding a strong horse.

Guido Rangoni had to make sure that all the men-at-arms that came to join the Bentivoglio army had the skill to ride as well to fight with the lance, warhammer and estoc. He also had to make sure that they came with the proper equipment. It was common enough for a light cavalryman to try and pass himself off as a man at arms, since the armored cavalry were paid twice as much.

Everything was happening at breakneck speed. The changing regimes in Bologna had sent many Bolognese into exile in Venetian country, and as the Venetian diarist Sanuto wrote, “…many Bolognese who were hiding in our lands have come forth, and with their horses crossed the sea to Ravenna.”

The infantry were coming in droves and Ravenna was full of partisans of the Bentivoglio; so many were coming that Cardinal Alidosi had to even issue a threat to take the property of any Bolognese that dared fight for the Bentivoglio. The money for the force was supposed to arrive on or around the 7th of May, and the force planned to head out for Bologna a week later. The Bentivoglio counted upon an invisible legion inside Bologna; Uncle Hermes had informants inside the city ready to help the Bentivoglio or so he told the Venetian authorities.[14]

To keep the enemy unbalanced and worried, Uncle Hermes launched light cavalry raids deep into enemy territory with another condottiere known as Johnny the Greek, at one time seizing as much as 140 head of cattle and bringing them back into Venetian territory.

Despite the efforts of the Bentivoglio the Venetians still held out little hope for a successful campaign in the south. They expected it to be little more than a nuisance for the Papal forces. They could not even find a Venetian official to manage the area, since to tie one’s name to such a hopeless enterprise was thought to be political suicide.

Despite the odds, Guido Rangoni and the Bentivoglio were determined to attack Bologna. The force was ready to move out for Bologna on May 15th.

Disaster

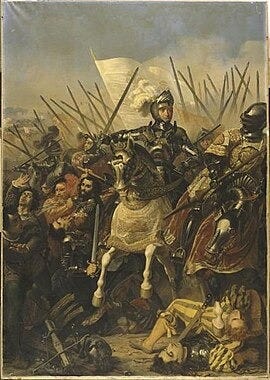

One hundred fifty miles to the northwest, a desperate battle was being fought. On the fateful morning of May 14th, the Venetian and French armies collided near the village of Agnadello. Commanding the Venetian forces was General Bartolomeo d'Alviano, a formidable figure whose destiny would soon intertwine dramatically with those of Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli.

Combat erupted when the French vanguard crashed fiercely into the Venetian rearguard, led by the courageous Pietro Monte. An intense, savage struggle unfolded as Venetian infantry braced against charging French heavy cavalry, pikes locked defiantly against the relentless thunder of armored lances. For a moment, the Venetians stood resolute, bravely holding their line against overwhelming odds.

Yet, the French were relentless, pouring in wave after wave of reinforcements. Seeing his rearguard in peril, Alviano boldly threw his entire force into the cauldron of battle, gambling all on one decisive clash. The battle reached its climax as the King of France himself, sensing victory within reach, personally led his remaining troops into the fray, unleashing the full weight of French power upon Alviano's beleaguered soldiers.

In a critical moment of betrayal, the Venetian vanguard's commander refused to support Alviano, choosing retreat over valor and leaving his comrades isolated and doomed. Trapped, surrounded, and overwhelmed, fully half of the Venetian army faced annihilation. Few managed to escape, spurring swift horses desperately from the carnage. Pietro Monte met his heroic end amidst the slaughter, and General Alviano, battered yet unbroken, was captured by the victorious French.

With shocking suddenness, Venice's proud army lay broken and demoralized, forever changed by the devastating tragedy at Agnadello.

Ravenna

News of the defeat spread rapidly across the Venetian Republic, sending shockwaves through its territories. The Bentivoglio family learned of the disastrous battle the very next day and immediately abandoned their plans to attack Bologna. Without Venice's backing, any attempt against Bologna would inevitably fail.

The catastrophic defeat at Agnadello was so devastating that Venice stood poised to lose “what it had taken them eight hundred years' exertion to conquer.” Though Venice still possessed half an army, it was thoroughly demoralized and now under the command of a man widely deemed a coward. Desertion was rife and disobedience a rule; Venetian commissioners were forced to offer bribes simply to persuade the soldiers to march. Cities within Venetian territory refused entry to their defeated army, fearing the wrath of the victorious French.

Desperately clinging to hope, Venice planned to regroup their armies near the sea. They ordered the Bentivoglio to remain in Ravenna and confront the Pope’s advancing army. But the city's walls were old, weak, and clearly inadequate against a determined siege. Recognizing Ravenna's vulnerability, and desperate for troops, Venetian authorities began sending ships to evacuate key elements of the Bentivoglio troops, planning to use them to rebuild their shattered army. Hannibal and Hermes Bentivoglio departed by sea for Venice, while Guido Rangoni stayed behind in Ravenna to command the thousands of Bolognese exiles seeking shelter within the city.

Faced with the grim reality of their situation, Ravenna’s Venetian governor sought terms of surrender with the Duke of Urbino, commander of the Pope’s forces. Under the negotiated terms, the Pope’s army gained control of Ravenna and its fortifications, while the citizens were permitted to leave peacefully, carrying their possessions with them.

Exodus

Many Bolognese considered remaining in Ravenna until they heard chilling news that Ramazzoto the Priest’s forces would soon occupy the city, posing an immediate threat to their property and lives. Responsibility for ensuring their safe passage into Venetian territory now fell squarely upon the shoulders of Guido Rangoni.

This perilous journey required crossing lands controlled by Guido Rangoni’s own lord, the Duke of Ferrara. Guido dutifully paid the Duke and negotiated terms for his people's safe passage through hostile territory toward the Republic of Venice. Despite these arrangements, the Ferrarese flagrantly violated the agreement only fifteen miles into the Bolognese journey. Armed and prepared, Ferrarese forces unexpectedly attacked the vulnerable travelers, plunging them into chaos. The Bolognese, although armed, found themselves vastly outnumbered and trapped on unfamiliar ground. The Ferrarese, with around 1,500 soldiers swiftly surrounded and overwhelmed the Bolognese convoy.

Resistance was futile. Realizing the hopelessness of their situation, the Bolognese reluctantly surrendered their horses, money, and valuables. Allowed to retain only their personal weapons and modest possessions, the survivors continued on foot, battered and impoverished.

Days later, the exhausted and destitute Bentivoglio refugees finally reached Padua, near Venice. Upon arrival, they dispersed—some seeking refuge in the relative safety of Venice, others joining the intellectual community in Padua, drawn by its renowned university. Hannibal and Hermes Bentivoglio had already moved ahead. Guido now went on ahead to his hereditary castle at Cordignano, preparing himself for the next dramatic developments in the tumultuous War of the League of Cambrai.

[1] Forgeng, p.208

[2] Forgeng, p.206

[3] Forgeng, p.207

[1] See Mallett & Shaw, p. 98. Note that the commanders were Pitigliano and Alviano but for simplicity’s sake, this work focuses only on Alviano.

[2] Sanuto, col. 12

[1] Specifically, Guido Rangoni’s sister was married to the father of Ercole Strozzi.

[2] Michele Catalano, p. 224 of Archivium Romanum vol 10. See also Lucrezia Borgia, Maria Bellonci, Phoenix Press, 2003. P. 325. Hercules Strozzi stood to inherit monies from the now-dead Hercules Bentivoglio that would instead go to a relative of the Bentivoglio Galeazzo Sforza. Hercules Strozzi had also earned the disfavor of the d’Este family for acting as a go-between in a romantic liasion between the Duchess of Ferrara and the Marquis of Mantua.

See Mallett & Shaw, p. 98. Note that the commanders were Pitigliano and Alviano but for simplicity’s sake, this work focuses only on Alviano.

Sanuto, col. 12