Is it the sword that makes fencing historical? The pluderhosen? The jackets? The shoes? The manuscripts and the treatises? The answer is, in many ways, all the above.

In order to recreate the arts as they were practiced, the objective of the modern partitioner is to explore all of these variables and investigate how they change the outcome of movement and coordination to build a historical martial dynamic. However, just as physical variables can affect the quality of our movement, a Renaissance mindset and an understanding of how scholasticism influenced fencing can affect the way we think about and conceptualize the texts as they were written.

I hope this lecture will be a guide that sparks your curiosity and sends you on a scholastic journey. Let’s begin.

It’s important to understand our inherent biases as modern people. We are the children of the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, the Computer Revolution, and we sit on the precipice of the AI Revolution.

Every leap in technological and moral reasoning that has advanced society and education over the last 500 years has put a barrier between us and the logic and reason of the ancients.

As you can see with the charts above, one of the more glaring statistical differentiations between our modern world and that of the medieval and Renaissance world is literacy rate. Now, it’s worth noting that these charts may not represent the vulgar linguae or vernacular of a specific population, and that may artificially depress these numbers. However, printing of books in vernacular didn’t really reach its peak until the late 15th into the early 16th century. There were certainly some, but volume and affordability were both facilitated by the spread of mass printing.

Cities with flourishing universities tended to fare better than those without. A rather incomplete but perhaps telling study can be drawn between the city of Florence—the capital of the Italian Renaissance in the popular imagination—and the bustling university city of Bologna.

In Florence at the turn of the 16th century there were anywhere between 2-4 grammarians teaching primary school educations to the youth of the city. By contrast, the commitment to education in Bologna was much more pervasive. In 1385—almost a century earlier—Bologna had 2-3 grammarians assigned to teach each district in the city, of which there were four. By 1439 this climbed to 4 per district; by 1480, 8; and by 1489 the number reached 12 per district for a total of 48 primary school educators city-wide. This effort was funded by the University and had a tremendous impact on the overall education and literacy of city.

The common curriculum of the age included Guarino di Verona’s Regulae, Cato, Ovid, Virgil, Cicero, Macrobius, Homer, and of course Aristotle.

As a consequence, what we tend to see in fencing manuals leading up to the late 15th century is a subjective standard for communicating the rules that govern fencing. These standards were often related in colloquial terms. For example, the names of the guards and leger used common iconography and carried a particular weight that may be unseen to the modern reader but would’ve been apparent to the contemporary practitioner.

One that example I’ve come across recently in my own research is a name we’re all familiar with, Porta di Ferro: the Iron Door. The easy superficial leap is to assume the iron gate of a city or castello, but in my experience the common word for the typical iron latticed gate of a city was referred to as a rastello, and the term Porta di Ferro was more commonly used to denote the heavy solid iron doors of churches and cathedrals, which acted as a safe place of refuge during a sack.

Now, this is a relatively multicultural audience. We all represent different backgrounds and geographical areas of the United States, and perhaps even the world, so let’s do a little exercise.

What is weird tradition your family has related to food?

For me personally, it’s eating sticky buns or cinnamon rolls with chili, and putting peanut butter on waffles: both weird Midwestern-Nebraskan things that make my Southern friends in the great state of North Carolina scratch their heads.

What are some of yours?

Similar regional variations, in things less consequential than food, can affect the way we relate things, or communicate standards across time. What I call BBQ is slow cooked pork marinated in tangy vinegar; what you call BBQ might be lathered in Sweet Baby Ray’s, or slow cooked over wood chips. There are several ways to cook a pig. We all call it BBQ, but we have a few different ways to achieve the same end, and it’s usually predicated on regionality.

Now, let’s dive into the heart of our subject matter.

One author who stands between this subjective age, and what I term the age of empiricism in fencing, is Pietro Monte. Now, given the literacy rate in Spain, for this exercise we’ll assume Monte was from Florence, though that isn’t much of a leg up—I’m kidding, I’m kidding.

Of course, we don’t know much about Monte’s early childhood education. It was probably quite good, though, considering he was a famous and revered courtier and peer of Leonardo da Vinci’s when he was in Milan. In fact, in his Collectanea, Monte gives us some wonderful insight into the world of humoral reasoning. So, let’s take a look.

First postulated by Hippocrates between 460-370 BC, this theory posits that there are four fluids that correspond to the four temperaments. They are blood, yellow bile, black bile, and mucus.

The body, when in homeostasis or balance, had equal portions of each. Imbalances or predilections toward an excess of a specific humor could alter mood, temperament, personality and health. This was the core principle of western medicine until the 19th century. In its development, this reasoning took on an astrological component, where birth sign and the alignment of planetary bodies could have an effect on humoral disposition.

This may seem preposterous by modern medical standards, yet the behavioral characteristics that compose humoral theory have remained the core tenants of western behavioral studies from Eysenck to Myers Briggs, the Ninja Turtles and the houses of Harry Potter.

Much of the continued study of humors dictating a person's temperaments was due to Galen in 190 AD. Galen proposed that the imbalance of pairs of humors resulted in one of the four temperaments.

Sanguine: optimistic and social. Choleric: short tempered and irritable. Melancholic: analytical and quiet. Phlegmatic: relaxed and peaceful. The humors themselves were dominated by the 4 qualities: warm, cold, moist, and dry. Warm and moist rendered a sanguine temperament; cold and dry, melancholic; cold and moist, phlegmatic; and hot and dry, choleric.

Here we have Monte’s dear friend da Vinci standing in for the author with Galen flanking the other side of the chart. What makes Pietro Monte’s work interesting is his application of Galen’s theory to everything from the quality of a horse to the predilection of certain nationalities toward specific temperaments, which he even extends to where men should be positioned in battle formation.

Monte believed that you should be able to spot the traits indicative of a specific temperament and determine an individual's disposition in the lead-up to a fight.

These are some of the characteristics that he highlights:

Sanguine folks have;: Broad, middling, fleshy face, heads that are neither small nor large, with thick necks, broad shoulders and thick upper limbs.

Phlegmatic people have: Large and fleshy heads and faces, with extremely long necks, soft bodies, with long limbs that are larger in their upper portions.

Cholerics have: Pale faces until stimulated, uniform heads, with normal necks, and proportional bodies, emboldened by uniform limbs with strong forearms and calves.

Melancholic individuals have: Faces that are bulging at the temples set with thick lips, and large round heads, short necks, and hard bodies that are dense with broad shoulders. Thick upper limbs with only moderate lower portions, that are often bowed.

Once we’ve judged the appearance of our adversary, we can expect the following dispositions in the fight:

A sanguine fencer, in the beginning of the work, shows the greatest vehemence of speed. Therefore it is best to hold back until their strength declines. Owing to their promptness and speed, sanguines quickly attack any exposed target, but the impetus quickly passes. Once he falters, we should close with him, since he is weak in the lower legs and loins.

To work in a contest of strength against cholerics, we should stay at a distance, because they have greater strength in the lower legs, loins, and forearms than in other parts of the body, so closing with them would be very harmful. Once we begin a fight with cholerics, it is useless to hasten or prolong it, for they almost always remain in a consistent mode, although in the beginning they seem to have a kind of obstruction before their eyes. Therefore, at every stage of the fight we should attack them, while guarding ourselves against them, and we should choose spacious places.

Melancholics are not quick in their manner of working, but they possess great hardness. Therefore, we should approach them temperately: this contrary is most excellent and effective against them. Because of their hardness we should not close with them, and also because most of them have great strength—even if they lack skill and agility. They can get by with their limited art when standing close, for in close grappling nobody can freely display agility. Standing at a distance or in arm-grapplings we can show more skill and agility, so with melancholics it helps to fight at a distance temperately.

When phlegmatics begin to work, they have little strength and a kind of looseness, so that is when we should show our ability against them. But we must finish the work very quickly, deploying our strength immediately so that we can take them with less effort. At the onset it seems that they feel nothing and falter like unskilled people; but if we hit them repeatedly, each time we probe we make them increase somewhat in strength, so that gradually their strength grows until it is no longer as easy to defeat them as it seemed at the start.

We can relate this to Meyer’s four fencers:

Frenzied/Violent:

(T)he first are those who impetuously cut and thrust as soon as they can reach the opponent in the Onset. When you take note that they want to quickly overwhelm you with hard cuts in the attack and want to crowd you…These fencers we can call Sanguine.

Artful/Coiled:

The second are somewhat more dissident and don’t attack so uncouthly; instead, when {their opponent} cuts or misses, drops too far, or otherwise fails to execute a change, they pursue and rapidly follow them to the closest exposed opening. These fencers we can call Choleric.

Judicious and Deceitful:

The Third don’t cut at an opening if they are not assured of it; instead, they pay more attention as to whether they can recover from the extension into the cut safely back into a counter-posture or to Defensive Strikes. (I {Joachim Meyer} hold myself with these [fencers], but it depends on my counterfencer. These Fencers we can call Melancholic.

Foolish or Cunning:

Now the fourth position themselves in a guard and wait thus for their opponent’s device; they must be either fools or especially sharp, for whoever will wait for another person’s device must either be very adept or also trained and experienced, or else he will not accomplish much. And these fencers we can call Phlegmatic.

We can perform the same exercise on Fiore’s Four Virtues:

One could argue that the four traits represent the virtue of each humor and when in balance construct the ideal fencer. Fiore says of the Virtues in the Morgan:

“Behold! We are the four distinguished Animals with these traits Who, for instance, strongly reminds that he is able in arms;

He wants to be clear/bright and even

Shining brightly with honesty.

He understands the lesson for himself,

And determines which are for harming.

Impress the evidence made known upon the spirit.

In the Getty the virtues are described thus:

Prudence/Wisdom:

No creature sees better than I the Lynx, and I proceed always with careful calculation.

Celerity/Speed

I am the Tiger, and I am so quick to run and turn, that even the thunderbolt from heaven cannot catch me.

Audacity/Daring

No one has a more courageous heart than I, the Lion, for I welcome all to meet me in battle.

Fortitude/Strength

I am the Elephant, and I carry a castle in my care, and I neither fall to my knees nor lose my footing.

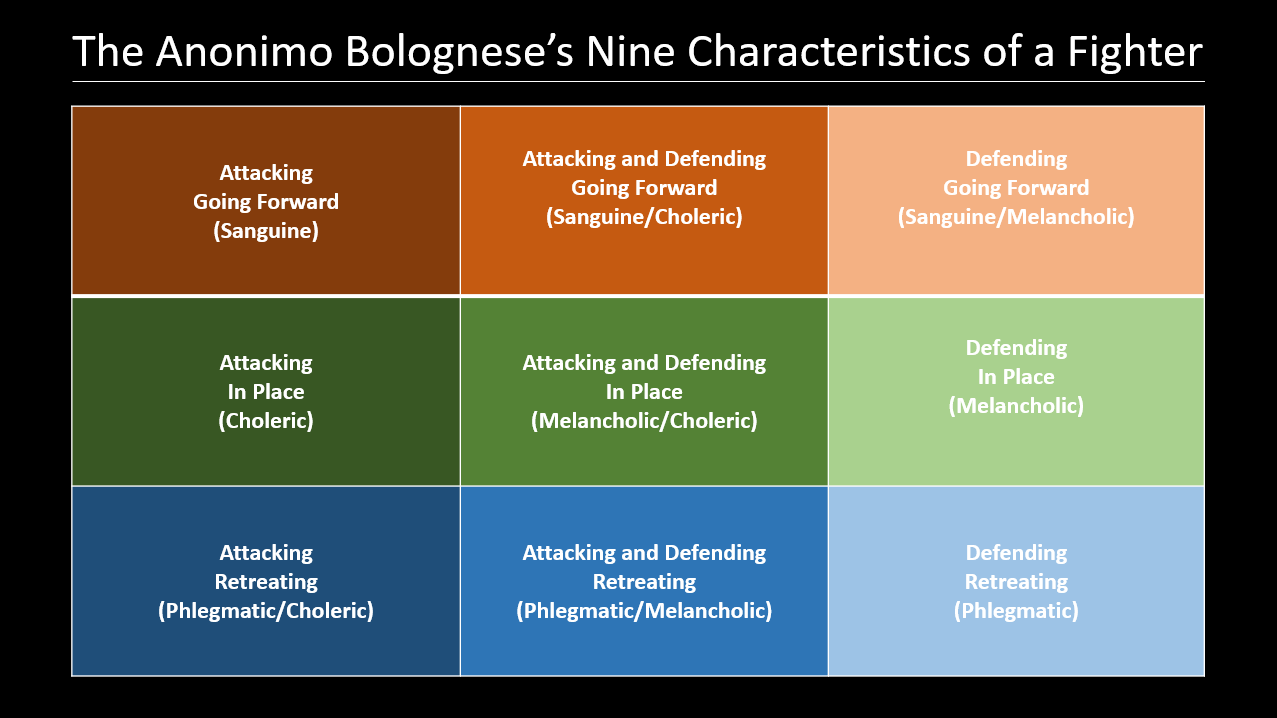

We can repeat the same exercise with the Anonimo Bolognese’s Nine Characteristics of a Fighter. In action this is an exercise in futility, as it over complicates what should become obvious though experience, however if we use it as a predictive model, then it can be a useful tool.

You all have index cards that were lying on your seats. I want you to write what you think best represents your fighting style on those cards using the Anonimo Bolognese’s 9 characteristics.

Now, I need a volunteer.

First, let me clarify, that this isn’t meant to be a cruel exercise. This is all in fun, but it needs to be stated that we will be assessing your physical characteristics to determine your humoral disposition, so if that isn’t something that you’d like to be subjected to please don’t volunteer.

Humor Game

From the Nine Characteristics and disposition, let’s turn to the core elements of fencing and the inherent variables that feed the equation that determines the success of an engagement.

We’ll start with measure!

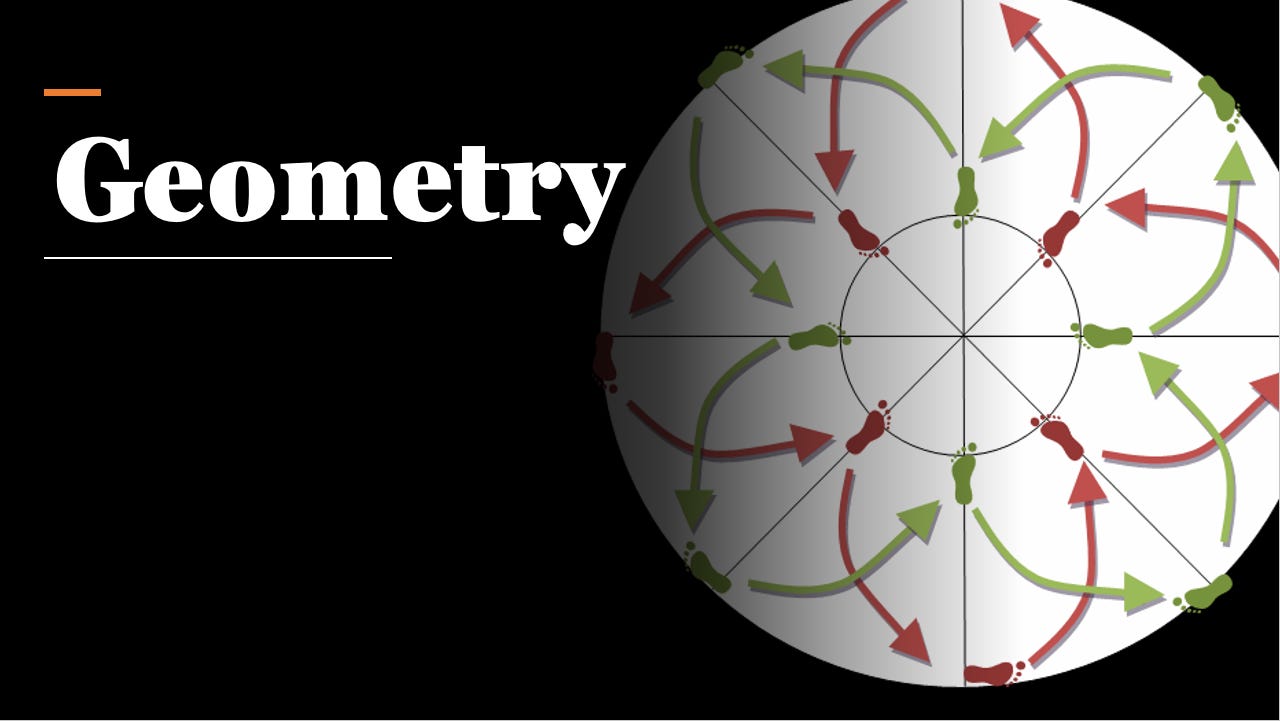

In Euclid’s Elements, he laid out a number of axioms and postulates that still rule geometry and fencing today. I’ll spare you the lecture on the history of mathematics and instead focus on how geometry, and more importantly measure, were conceptualized, rationalized, and realized in fencing. There was perhaps no greater shift in the evolution of fencing than what we can term the Euclidian Revolution. But measure has always been paramount—don’t take my word for it, listen to these guys:

Liechtenauer said, “This you should grasp: All arts have length and measure.”

Dardi dictates: “(G)eometry, resembles the skill of fencing because in fencing there is nothing but proper measure.”

Vadi relates: “And if you heed my doctrines, You’ll know how to answer with reason And pluck the rose from the thorns. To make your opinion clearer, And to sharpen your intellect, So you may be able to answer to everyone: Music adorns her and chooses her as its subject, Song and sound are added to the art, To make it a more perfect science. So Geometry and Music combine Their scientific virtues in the sword, To adorn the great light of Mars.”

And Fabris proclaims: “We have shunned the use of geometrical terms, although swordsmanship has its foundations more in geometry than in any other science. Simply and as naturally as possible we have tried to bring the art within the capacity of all.”

The first synthesized model to show up, I believe, is the segno. Originally illustrated in Achille Marozzo’s Opera Nova in 1536, it’s unclear if this pedagogical device predates Marozzo, but from my own personal analysis of the fencing system and various authors, I’ve found enough indication to presume that it likely did.

The segno is a relational model that denotes various passages of play, or modes of fencing. In Bologna, these were referred to as gioco largo, gioco stretto, and mezza spada. We can see similar terms used for the demarcation of measure utilized in the Holy Roman Empire with the zufechten, krieg, and ringen am schwert, and in the earlier recorded Italian traditions of Fiore and Vadi, where their expressions of measure are predicated on the depth of a crossing.

The segno as a tool was intended to teach the coordination of the sword with the body and dynamic footwork patterns, notably sideways and oblique movement. Utilizing Marozzo’s prescribed plays—that is, his sharp sword plays in book two—and similar actions from the tangential authors, we can see that one of the main objectives of the segno was to emphasize angulation and leverage. Perhaps one of the better illustrations of this, ironically, comes from the Basel-born Swiss fencing master Joachim Meyer, who relates:

“Item: If you both stand on line A as previously mentioned and he cuts at your right and then thrusts straight at you, then thrust in likewise with him and step with your left behind your right on the B line to the right and follow further with your right foot to the C line to the right, thus his thrust fails and yours meets. However, if he also steps like you are stepping, then both thrusts parry each other.”

This is a principal key to northern Italian fencing.

This plural approach would remain a core tenant of Italian fencing for an age, but the mid-16th century saw a new mode of expressing measure dominate the landscape and change the course of fencing forever.

Enter the Reformers Sandro Francesco Altoni and Camillo Agrippa. The 1550s saw a slew of new approaches to the stale zeitgeist of the Italian Wars era. Most notably, a singular, interpersonal approach to defining measure, where the proportions of the individual, and the emphasis on delivering the shortest, most concise tempo, came to rule the age.

Let’s talk about time…

Time, or tempo, in fencing has largely been measure as a function of Aristotelian physics. Aristotle defined time as a number of change with respect to the before and after.

Put in fencing terms, this is simply guard—motion—guard.

Of the extant sources, the first person to reference tempo as a function of fencing was Filippo Vadi. This is unsurprising given his education as a medical doctor, during which he would’ve studied Aristotle as a core part of his curriculum. What we see from Vadi through the Bolognese authors and on into the modern age of fencing is an empirical emphasis, where defining, categorizing, theorizing, and refining the rules that govern fencing became the focus of the given age. Just as theory and application of various ways of defining measure changed the landscape of fencing, tempo and its range of applications also had a transformative effect.

One of the first syntheses of tempo from a perspective of applied philosophy comes to us from Angelo Viggiani, who says:

“All right, it suffices that each motion that is single and continuous lies between the preceding and subsequent rest; look, then, Conte: before you throw a mandritto, a rovescio, or a punta, you are in some guard; having finished the blow, you find yourself in another guard; that motion of throwing the blow is a tempo, because that blow is a continuous motion; thus the tempo that it accompanies is a single tempo; when you rest in guard, having finished that motion, you find yourself once again at rest; it is therefore a tempo, a motion, which instead of calling a “motion”, we call a “tempo”, because the one [64R] does not abandon the other; and the guard is the rest and the repose in some place and form. In conclusion it is as much to say “tempo” and “guard”, as it is to say “motion” and “rest”. Whereby it is necessarily so, that as between two motions there is always a rest, and between two rests there is interposed a motion, apparently between two thrown blows, or two tempos, or two motions, is found a guard. And between two guards, or rests (as you wish to say) are interposed some blow and tempo.”

It’s of little consequence that this expression is first related in dialogue by Viggiani’s muse, Ludovico Bocadiferro—here shown hoarding the Funyuns—before being clarified by Rodomonte. Bocadiferro was the star student and presumed heir of the greatest Bolognese philosopher, Alessandro Achillini, a man whom his peers called the second Aristotle, and was also a member of the Bentivogleschi faction, which is at the heart of the Bolognese fencing tradition. One of Achillini’s final works before his death in 1512 was a commentary on Aristotle’s physics called De Proportionibus Motuum. This was published posthumously by his younger brother, Giovanni Fioloteo Achillini in 1516, who himself published a treatise on the mezza spada techniques of Bolognese fencing in his Viridario, published in 1514 but written 1504.

Tempo and measure are two key variables that combine to dictate the outcome of almost every fencing engagement. We see this expressed succinctly by Antonio Manciolino, who says that a fencer may strike their opponent without tempo and measure, but that doesn't redeem their bad form: “we call those who strike with tempo and elegance Gravi and Apostati.”

For Marozzo, the tempi are a means to an end, and that is creating crossings, so he can work artfully in the engagement, and exit safely. You could argue that many of the expressions of tempos of attack fit in this dichotomy.

To summarize, tempo is almost universally expressed as any movement of the sword or body, and how these tempi are exploited is often up to the discretion of the author. However, one of the core components that is almost universally expressed is the general axiom of acting with a smaller tempo, in the tempo of your opponent, with the proper measure.

Tempo game:

Lecturer counts One—and—Two, varying the speed of the count. The audience claps on the ‘and’.

Now it’s time to poke the bear and get theoretical.

The following three quotes will be important for understanding what were about to discuss:

“First mark and remember that Liechtenaur’s Fencing is aligned at the Five Words Before , After, Weak , Strong, Indes; these are the principles and the fundament of all fighting…”

“And this is what Liechtenauer means by the words, "Soft and Hard" And this follows the authorities. As Aristotle spoke in the book Perihermanias: "Opposites positioned near themselves shine greater, or rather; opposites which adjoin, augment. Weak against strong, hard against soft, and the contrary." For should it be strong against strong, then the stronger would win every time.”

“Because of this, the two words, The Before, The After, that is the Vorschlag and the Nachschlag, arise. Continuously and in one moment as if left without any middle.”

In MS 3227a, the author relates the words Before and After, Strong and Weak, to Aristotle's qualities in opposite categories. This can be found in Aristotle’s work titled Categories. In part 10, Aristotle describes, “the various senses in which the term ‘opposite’ is used.”

Things are opposed in four ways: As correlatives, contraries, privatives and positives, and affirmatives and negatives. A general rule of correlatives is that all relatives have correlatives; that is, by ‘greater’, you mean greater than that which is less; by ‘less’, you mean less than that which is greater.

For contraries we have to see them as pairs of opposites, like he is sick and he is well. This is generally the case unless correlatives have intermediaries. Then they have a transitive property, an in-between. Like the colors black and white: their intermediary is grey.

On to privatives and positives, which usually denote that what you once had has been lost: for example, he is blind and he has sight; she has teeth and she has no teeth.

Affirmation and negation are the last quality, and for this quality, one opposite must be true and the other false.

For the following exercise we’re going to explore the ideas of strong and weak, and before and after as each category of opposites. For the sake of time, I’m going to go ahead and forego affirmation and negation, because I don’t think it’s a likely scenario. I could certainly be wrong, but my reasoning is simply that it would seem illogical for me to be strong, and it to be false that you are also strong or can be strong. I’ll admit that this does strike a chord with Vor and Nach, and I encourage you to explore that possibility.

Correlatives, as defined by Aristotle, are pairs of opposites which fall under the category of relation and are explained by reference of the one to the other, the reference being indicated by the proposition ‘of’ or by some other preposition. If we were to take the definition of correlatives and apply it to strong and weak, before and after, we could draw some interesting conclusions.

Looking at the positive, which is before, then by Aristotle's standard, it would mean that I had more before than the before of my opponent. This is certainly true, and you can form a logical argument around this notion. Similarly with strength: again using the positive trait, it would mean that I have more strength than the strength of my opponent. That certainly makes sense, especially if we take strength as a function of biomechanical leverage.

Where I feel this could fall short is its relation to the text of 3227a specifically. This could certainly be more logical, and it could better fit your experience personal experience of KdF than the author of 3227a’s supposition, but this exercise is meant to be an analysis of how the author perceived KdF in relation of Aristotle, so we must maintain that standard.

First, the author of 3227a says that “opposites positioned near themselves shine greater. Or rather opposites which adjoin augment.” The quality of the relationship seems to need to have a weak, or a weakening component to work, “weak against strong, hard against soft.”

Surely, the last statement confirms that for us, “For should it be strong against strong {more strength than the strength of} then surely the stronger would win every time.” So, it’s not that this is illogical by any standard, it just doesn’t reflect the nuance of the tactical objective—not in my reading of it.

The argument of Strong and Weak, Vor and Nach, does lend itself well to the principle of frequens motus illustrated by the quote, “Here note that constant motion according to this art and lesson arrests the opponent in the beginning, middle and end of all fencing. In this way you complete the beginning, middle and ending in one fluid motion without pause and without hinderance of your adversary and you do not allow the opponent to come to blows with anything.”

Now that we’ve examined correlatives, let’s move on to contraries.

According to Aristotle, “Pairs of opposites which are contraries are not in any way interdependent but are contrary to one another. Those contraries which are such that the subjects in which they are naturally present, or of which they are predicated, must necessarily contain either one or the other of them, have no intermediate, but those in the case of which no such necessity obtains always have an intermediate.”

An example of a contrary without an intermediary would be odd and even numbers, or heat from a fire. An example of a contrary with an intermediary would be good and bad, where the goodness of an individual is not necessarily a function of their goodness, but a function of them being less bad than a bad person. Therefore, by contrast, when they are in opposition to the bad person, they are comparatively good. A less nuanced example is the colors black and white, where the color grey is an intermediary between these two extremes.

It’s my belief that the function of Before and After, Strong and Weak as contraries hinges on the role of the intermediary.

Aristotle says:

“Yet in the case of those contraries which have an intermediate we found that it was never necessary that either one or the other should be present in every appropriate subject, but only that in certain subjects one of the pair should be present, and that in a determinate state.”

And

“Again, in the case of contraries, it is possible that there should be changes from either into the other, while the subject retains its identity, unless indeed one of the contraries is a constitutive property of that subject, as heat is of fire.”

This echoes the words of the author of 3227a in a way that really intrigues me. That a subject present in a determined state has no intermediary, and when an intermediary is present in the relationship that it can effect change in the relationship between the opposed parties.

If we assume that having the Vor is obtained by striking the vorshchlag—when it is appropriate and achieves a strong position—and chasing the openings; we can see the Vor as an act of pursuit. The continuation of this pursuit puts the opponent in the Nach. The means of achieving and maintaining this relationship is through the principle of frequens motus. As, 3227a’s author states that the execution must be performed, “continuously and in one moment as if left without any middle.”

That is, to my understanding, performed in a determined state with no intermediary, or in Aristotles definitions “to make do” and to “suffer or undergo”.

As long as the subject of the pursuit remains in a determined state, then the fencer who is pursuant will maintain the Vor.

But what happens if their pursuit wains, or their opponent interrupts their pursuit with a skillful action that disrupts their frequens motus?

Then, the focus or subject changes.

The principle of frequens motus is predicated on acting before the opponent can come to a fully formed guard position. That is, before they complete their strengthening or weakening in response to your action in pursuit.

Were they to achieve their state of strength or weakness, the subject would change to this relationship in the quality of the bind or crossing.

Similar to the qualities of the subject that dictated the possession of the before; a determined state vs the presence of intermediaries—the conduct of this relationship between opposites in contrary categories is dependent on the use of fuhlen to correctly calibrate whether your role is to strengthen or weaken in response.

Here again, the author notes that opposites positioned near themselves shine greater, or rather opposites which adjoin augment. Weak against strong, hard against soft. The fencer who through fuhlen recognizes the nature of the relationship first can act indes and claim the Vor, whereby the subject changes back to the pursuit.

Similarly, if one or the other party try to strengthen when they are weak, or weaken when they are strong, they will introduce an intermediary, wherein their counterpart may act indes and work in the Vor. This concentric, bipolar relationship will go until someone is struck decisively or the measure is reset to the Zufechten, where the quality of the bind is indecisive.

Now let’s take a look at privatives and positives! Aristotle defines these like this:

“Privatives and Positives have reference to the same subject…It is a universal rule that each of a pair of opposites of this type has reference to that which the particular positive is natural.”

To apply this succinctly to Strong and Weak, we could say, the strength of the stronger party takes away the weaker party’s ability to be strong in relation.

For Vor and Nach, we could craft a similar statement: the Vor is a condition of the party who strikes the Vorshlag, which denies the party in the Nach the ability to be in the Vor.

Here if we were to apply a similar lens to the one we used to observe opposites as contraries, that my strength executed in frequent modus deprives you of the ability to come to a position of strength yourself, then we could view both Vor and Nach as dominant—positive subjects, and Nach and Weak as states of privation. These relational characteristics are intriguing because they give a definitive stepping of point for when to stop pursing the vor. That is when your frequens motus has been compromised and you can no longer achieve a strong position in relation.

Whichever way you cut it—contraries, correlatives, privatives and positives, there is a lot to explore with 3227a’s observation of Aristotle in Liechtenauer’s teachings.

Of course, I would be remiss not to take a moment and define how strength and weakness are derived in fencing. A fencer can exert strength in roughly three ways; I’m sure I’m missing another, somewhere. But these are my three:

Through force: pushing, driving, projecting or tensing; kinetically.

Mechanically: that would entail aligning the mechanical leverages of the sword against the opponents: for example, strong vs weak, or edge vs flat.

Body structure: deploying larger muscle groups—hips, core, back—to resist or overpower weaker muscle groups like the arms.

Of these three options, mechanical leverage and body structure are superior, as force or kinetic responses are often reactionary. I think Puck Curtis put it best: we don’t often get the floor knowledge from the authors that help us develop the former two.

But the notion is certainly there:

“With your whole body shall you fight,

For that is how you fence with might.”

“This ingenious art of the sword consists above all of a half turn of the hand or a full turn of the hand; and this half turn or full turn of the hand needs to accompany a half blow or a full blow; and this half blow or full blow needs to be accompanied by a half turn of the body; and this half turn of the body needs to be accompanied by a half or full step…”

For my Sauce-loving friends, you could argue that the topic of frequens motus isn’t unique to KdF, as we see a similar concept illustrated in the Opera Novas of Manciolino and Marozzo as well:

Marozzo says:

“You should hold it to be a certain factor that no one who is attacked when raising out of a guard, or in falling from a guard, can perform any counter except for an instinctive response as if he knew nothing…But if perchance you were to attack him when he was neither rising nor falling, be advised that he could interrupt your intention with a variety of blows. So if you wish for honor, be attentive, and look to attack him as he rises or falls from his guard with his counters.” (Marozzo, Capitolo 171; Swanger, pg. 256)

To which Manciolino adds:

“Since no blow can be reasonably performed without ending in a guard, the virtue of a fencer is to be found in the raising and lowering of the guards. In consequence of this principle, he who renews his attack before settling in guard will be more apt to win. This is because it is easier to attack an opponent whose action is interrupted.” (Manciolino; Leoni, pg. 112)

Alright, enough of the easy stuff, let’s get into the real meat and potatoes of the lecture…

So far, we’ve discussed the nature or disposition of a fencer, measure, tempo, strong and weak as relational qualities, and the concept of frequens motus as a key function of the Vor.

Now let’s return to our dear friend Alessandro Achillini and keep this Aristotelian Scholatic train-a-rolling!

In order to understand Achillini, we have to take a brief survey of the history of philosophy, with a keen focus on its application and understanding in the European sphere. To do this effectively, we must first understand Platonism. The core tenant of Plato’s philosophy we are going to explore, is his answer to the problem of Universals.

Universals can be reduced in this way: if things share an attribute, a feature, or a quality, then the particular commonality among those things is a universal.

In Platonism, Universals are representative of forms. To Plato, these forms existed outside of space and time and possessed a higher reality than their terrestrial counterparts.

To understand this further, we can explore the following example:

A red cup and a red apple share the particular quality of redness, and this redness is a Universal.

If I were to break the red cup, I wouldn’t destroy the Universal of redness or cupness, only the object that represented those qualities.

Particulars are simply defined as individuals or entities that exist and occupy a certain space in time. Everything that surrounds you; the cup, the apple, you sitting there in the audience is a Particular. A good way to remember this is that a Particular exists in itself, while a universal exists in something else.

Form -> Universal -> Particular

Rather than Universalia Ante Res; or Universals before things, Aristotle argued Universalia in Rebus; or Universals in things. The dichotomy is a point of contention illustrated in Raphael’s School of Athens, with Plato pointing up and Aristotle pointing out.

In the words of Bob Hale, “Aristotle believed that while there are Universals, they can have no freestanding, independent existence. They exist only in the particulars that instantiate them.”

So, the red particular of our cup presupposes the Universal redness it shares with the apple.

While Aristotle didn’t believe in transcendent forms, he did argue that beings developed toward an ideal form, and that the focus of the individual was to strive toward that perfection before they begin to decay. A notion we’re all familiar with on our martial arts journey—no doubt.

In summary, Aristotle believed the order should be Particular then Universal.

Aristotle’s more empirical approach to logic inspired the 12th Century Iberian Muslim philosopher Ibn Rushd, known as Averroes to reconcile his faith with the logos of the ancients.

Averroes concluded that philosophy was superior to faith and knowledge founded on faith, that natural truths were sufficient. That the purpose of philosophy was to establish the true, inner meaning of religious beliefs and convictions. To justify this, he argued the idea of Universal cognitions: Dater Formarum, or the creator of forms, which is the active agent in intellectual reasoning. In this idea, this intellect contains not Universal knowledge, but the active consideration of Particular things.

Because Averroes wrote a number of commentaries on Artistotle that were translated from Arabic into Latin, his works and his reflections became widely circulated in Medieval Europe, where two interesting tenets arose: that man could manifest his own happiness, and the rejection of both moral determinism and the existence of the eternal soul.

You can probably see the storm clouds a-brewing!

While Averroes’s translations were widely utilized and circulated, you can imagine the controversy that struck when the secular universities in the Christian West started analyzing and teaching his commentaries.

The first apologist to step-up to the plate and try to take a swing at Averroes’s fastball was someone you’re all probably familiar with, Thomas Aquinas. For the sake of brevity, Aquinas concluded that reason was capable of operating within faith, and was very critical of Averroes, despite using his translations often in his works.

These competing monistic analyses of Aristotle’s reason would set the stage for the development of western philosophy moving forward and were the source of more than a handful of student riots across Europe—especially in Paris.

Tired of all the contention, Siger of Brabant thought that he’d found a way to cut the Gordian Knot.

He argued that one thing could be true through reason, and the opposite could be true through faith.

For example, if we observe that the great 20th century poet-philosopher Bret Michaels is correct—that every rose has a thorn—and I therefore associate roses (let’s call them red roses) with pain, while you my beautiful audience associate the rose only with its innate beauty, both of our collective experiences can be a part of the greater cognition of the truth of the rose.

My forlorn power ballad can be just as valid as your unsullied admiration for the rose. All of this was so that Siger could enjoy the dogmatic and empirical realism of Aristotle as it was related by Averroes, with the wonder and majesty of his Christian faith.

Of course…his fellow faithful didn’t agree. They had Siger excommunicated for heterodoxy, or arguing two truths.

However dour this may have been for dear Siger, while he was excommunicated from Catholic heaven, he made it into Dante’s Paradisio as one of the 12 illustrious souls—so he had that going for him.

While Siger ’s compromise may have been a hit at Parisian frat parties, it wasn’t dank enough for the College of Cardinals.

Enter William of Ockham!

Ockham said to hell with the complexity, the uUniversals, and the Greco-Islamic realism: God made the rules, he’s not subject to the rules. Universals don’t explain the existence of God, they’re just manifestations of language, devices conceived by man to generalize Particulars in an attempt to understand the mystery of creation.

He argued that there are only Particulars, no realities or cognitions, just individual, measurable, tangible things. This, of course, led to the conceptualization of his famous Razor.

“Plurality must never be posited without necessity.” Or, simply, the least complex explanation is the most likely explanation.

Now we can talk about Alessandro Achillini!

Achillini was a proponent of Averroes and Siger of Brabant, and it’s perhaps through Siger ’s compromise that he was able to rationalize, embrace, and evangelize the ideals of William of Ockham, leading an Ockhamist revolution in the city of Bologna in the late 15th early 16th century. What we see in Achillini’s philosophical discourse is a synthesis of these three stalwarts.

To Porphyry’s questions, whether Universals are in the intellect, and whether Universals are real, Achillini answered:

“We experience that the Universal is in us” —using Siger to justify Averroes—“and every kind of knowledge presupposes it” —driving the point home with Ockham. Porphyry was a Platonist, and his questions are a challenge to Aristotle’s claim that sensible substances are prior to the Universal Species and Genera…

To rationalize this…follow me here:

When your plane crashes in an undisclosed location somewhere in East Asia, and you encounter a tiger in the wild, you can either; stop and wonder if that majestic beast is a Bengal or a Siber-aargghghgh.

-or-

You can say “Oh shit” and try to find shelter immediately. Fighting, much like random tiger encounters after tragic plane crashes in undisclosed parts of East Asia, require quick, concise, decisive action. No Mind. A focus on the sensible substances, as Aristotle would say, and less on the Universals they compose.

Whether Achillini’s nominal Aristotelian approach had any effect on Achille Marozzo, we’ll likely never know, however, there is something curiously nominalist about Marozzo’s work. Juxtaposed to his contemporary Antonio Manciolino, who loves to quote ‘the Philosopher’ and swing his humanist education around with plodding allegories, one might write Marozzo off. But Marozzo is no schlub; he subtly includes some pretty complex philosophical models in his new work. For example, the clever exposition on frequens motus we saw in our expose on 3227a. More importantly Marozzo preaches, time and time again, what I believe is nominalism in defense.

“I want to make it understood that when a man delivers a blow, he can only throw three kinds of attacks naturally, namely a mandritto, a riverso, or a stocatta. There are those who will say that there are more than these aforesaid three attacks that can be done, and I will confirm to you that indeed there are; that is, there are many kinds of attacks, but regardless of whatever blow is thrown in the beginning one can’t do any other than those aforementioned three.”

Who cares if it’s a Bengal or a Siberian tiger. It’s a freaking tiger!

Who cares if it’s infalso, impuntato traverso, or mezza?

Is it a mandritto (cut from the right), a roverso (cut from the left) or a stocatta (a thrust)? It is the sensible substance that precedes the Universal that matters in the moment.

Let’s take a moment to appreciate where genera and species do come in handy, and spend some more time with our dear friend Angelo Viggiani.

Using what we’ve learned about Particulars and Universals, we know now that particulars exist within themselves, and universals exist in something else, yeah? Everyone likes to throw shade at my boy Angelo for his guards, but I’m going to show you why they’re ingenious! This is an exercise in logic!

Viggiani identified 7 particulars of a guard position:

Whether the sword is on the right or the left

Whether the point is on-line or off-line

And whether the sword is high, middle, or low

Guards on the right are generally offensive

Guards on the left are generally defensive

Guards with the point on-line can thrust and cut (perfect)

Guards with the point off-line can cut (imperfect)

Guards that are high are offensive, and guards that are low are defensive

The purpose and beauty of this exercise lies in its predictive outcome—just like Monte and his dispositions. In the pre-fencing, whether sanguine or phlegmatic, whether you’re offensive or defensive, having the foresight to understand the innate quality and potential of each guard position will allow you to act decisively.

This can be determined by defining the genera and species of each guard. Offensive or defensive, our genus: and perfect oriImperfect our species. Now, we’re afforded this moment of speciation because there’s no tiger we need to worry about: as long as we’re aware of our measure and the tempo, then the threat is not immediate.

At the onset of a fight, we are the hunter, and as Marozzo loves to say, we’ll Caccia our opponent out of the refuge of their guard, but in order to do that well, we must know the underlying potential we're provoking.

This is supported by two key quotes:

“And so, we have taught and given the knowledge of the gallant guards that pertain to this ingenious art of defense, for there is nothing in this art that you need to understand more readily. This way when you find yourself against an enemy, you can immediately identify how the swords are placed, for the attacks one may make with the sword are infinite and innumerable, and so too are the ways in which the swords may be found; yet from one guard or another, not all attacks will be suitable, and by being shrewd, and also being illuminated with the knowledge of your enemy's placement, you will make effective attacks, in the correct tempo, using your sword and your body; and by making attacks in this manner you will remain secure from harm.” —Anonimo Bolognese (Fratus, pg. 59)

And

“Always keep an eye on the opponent’s sword-hand rather than his face. By looking at his hand, you will be able to devise all that he intends to do.” —Antonio Manciolino (Leoni, pg. 110)

To draw this foray of reason to a succinct conclusion, it’s appropriate to end with one final logical device, and my favorite author, Antonio Manciolino.

Oh Antonio, how oft misunderstood you’ve been!

Manciolino, in his Opera Nova, gives plenty of clear, listed, tactical approbates, but the way he illustrates the greater tactical paradigm of Bolognese fencing is presented in allegory.

For wide play we have the resplendent Nymphs, who:

“Not grace, for just as rich fabrics adorn the charming and lovely Nymphs lightly treading on Mount Menalus or in the Lyceum, so does supple stepping embellish the blows of the dazzling sword. Were our weapon despoiled of its proper steps, it would fall into the darkness of a serene night being orphaned of the stars. And how can white-clad Victory be, where gentle grace is lacking?”

To which he concludes, “We shant therefore call him victor who wins by chance and throws random blows like a brutal peasant; nor shall we call vanquished him who proceeds according to the correct teachings. It is indeed more respected among knowledgeable men to lose with poise than to win erratically and outside of any grace.”

And later contrasts with:

“Much more joyful than our Martial Plays are the assalti that rough-haired Satyrs conduct toward hunting nymphs in the pages of poetry books. Those subjects are so fine that words compose themselves for the poet in a sweet ever-flowing style.”

To which he adds a graphic depiction of the chase:

“When bards attempt to tell of Goat-gods’ wooly limbs, their horny brows, their gestures so licentious, words are not composed, but hues on canvas paint their rustic charge, while breathless nymphs a-flee.”

Our licentious wooly goat-gods are of course a metaphor for narrow play, or fencing from a crossing, to which Manciolino says:

“He who doesn’t understand it perfectly and does not have an excellent foundation in it will never be a good master. No matter how good a fencer, how skilled in defense and how quick with his hands, he will be unable to teach the true art to others, since true art consists in being strongest and most resilient. Rather than knowledge, these fencers should more aptly be considered lucky when they score a hit.”

So, we must have the poise and grace of the Nymph for our victory to be judged complete, yet the rustic charge of the Satyr with its strength and resilience is a necessity for our mastery to be complete. But how do we reconcile these forces in opposition?

Manciolino continues:

“He who fails to praise the splendid colors of polished literature, the elegance of well-composed speech, and the harmony of poetry would rightfully be deemed insensible. Yet, it would be equally insensible to adopt the same form of speech in a topic for which it is unfit. Therefore, a wise writer always creates characters who speak and reply in a manner befitting their condition.”

We’re called to be neither the Nymph nor the Satyr, but the Author, who can compose their art with the timid grace of the Nymph and the reprobate veracity of the licentious Satyr; all without ever being corrupted by the mind of either.

And this brings us to our conclusion.

Whether you’re doing I.33, Fiore, KdF, Bolognese fencing, or recreating the arts of the 17th and 18th centuries, our objective is all the same: a pursuit of understanding and renewal.

Whether your method is Universalia ante Res, Universals before things—as in Plato— or Universalia in Rebus, Universals in things—as in Aristotle—or even a belief in the dater formarum, the Universal cognition, and the active agent in intellectual reasoning—as in Averroes—our objective and the objective of the authors who composed these works on fencing is or was logos: reason, principle, or the order that governs this wonderful art we share.

Just as dialogue and discussion are at the heart of Logic, they’re equally important for this project we endeavor to revitalize. Some may find compromise in the wisdom is Siger of Brabant, that there can be many truths derived from subjective experience, or they make take a more empirical Ockhamist approach and focus on the things which are quantifiable, measurable, and tangible. Regardless of how we come to the table, we must remember that we are all the authors of our fencing narrative, and therefore we must speak with the voice appropriate of the moment, and engage in the discourse that will bring us closer to understanding the particulars of this forgotten art.