If you watched A Game of Thrones or read A Song of Fire and Ice, then you must remember the Red Wedding. Renaissance Italy had its own famous Nozze Rosso dei Baglioni or Red Wedding of the Baglioni. The Baglioni (pronounced Ba-Lyee-Oh-Nee) were the dominant family of Perugia, an ancient hill city some 100 miles east of Florence. If you’ve been following our epic tale of the duel between Hugo Pepoli and Guido Rangoni you will remember John Paul Baglioni as the general whom Hugo Pepoli served as a lieutenant.

The summer in the year of 1500 was a time of great promise for the House of Baglioni. They had just secured a marriage alliance between the head of their family, Astorre Baglioni and the mighty Colonna family of Rome, one of the most powerful houses in Italy. Eleven days of nuptial celebrations were planned.

Weddings were enormously important to the culture of Renaissance Italy. They had mouth-watering feasts, music and dancing, and of course martial games like jousts where the knights of the land showed off their skills. The violence was supposed to be contained to these games.

But there were no hard and fast rules in turbulent Italy.

Just as now weddings were also an occasion time for members of a family to gather from all points of the compass to celebrate together. Like many prominent families in Italy, members of the Baglioni family served as soldiers of fortune or condottieri, to the various Italian powers, none more conspicuously than John Paul Baglioni. This wedding offered a rare chance for all the Baglioni to “catch up.”

But for Griffin Baglioni, the leader of the junior branch of the family, it was also a rare chance to eliminate the senior branch of the family in one night. Griffin felt that John Paul Baglioni and his cousins had pushed him aside, and he determined to be rid of them. Thus was born the Red Wedding.

As in all Italian families, tension had simmered for years between the junior and senior branch. This was no surprise. A nun with powers of divination even had a vision of a murderous rampage between the different sides of the Baglioni clan in Perugia. Griffin’s mother had even consulted with this nun, who warned the conspiracy would come to no good.

Regardless, Griffin and his brother Carl decided to push on with the plan. Their primary target was the bridegroom, Astorre, who was also the acknowledged head of the family. On the night of July 14th Astorre was staying as a guest in the house of Griffin Baglioini. In the late hours, Griffin came with a group of armed men to Astorre’s bedchamber and slew him.

Griffin and his conspirator soon killed Asttore’s brothers and finally gathered together to make their attack on John Paul Baglioni.

According to Matarazzo this is what happened next:

“…all these [murderers], I say, went to the chamber where that noble Lord (John Paul Baglioni) was used to sleep, and entered in, and there they found one that wa^ a servant or attendant, and him they slew — that is, Carlo with his own hands slew him, thinking that he was His Highness Giovan Paolo. And when they saw that it was not he, they turned to go to the rooms above, and as they went up the stairs they found him at the stairhead with a buckler in his hand and his sword drawn. There he stood in his shirt, and with him was a companion, a man-at-arms, whom he loved dearly, Maraglia the Perugian. He had a spiedo in his hand, and when the enemy would have climbed the stair to slay his lord, the same Maraglia struck at them with his spiedo, pricking them in the breast above the cuirass and tumbling them down the stairs; and he smote so lustily with his spiedo that his lord had time to get out through a small window on to the roof of his house…

--Matarazzo, from the Chronicles of the City of Perugia.

John Paul Baglioni escaped by taking to the roof of the house then fleeing eventually into the Sapienza – a famous school in Perugia. There he dressed himself in the robes of a student and left Perugia to rally men to his cause. Soon he would pay back Griffin and Carl for their murderous deeds.

Yet, but for one trusted man-at-arms with a spiedo, the plot would have come to success.

So what is a spiedo exactly and why was it used?

Anyone familiar with early 16th Century fencing masters will have some familiarity with this weapon, though it’s not a weapon many sword nerds have heard of in the Anglosphere.

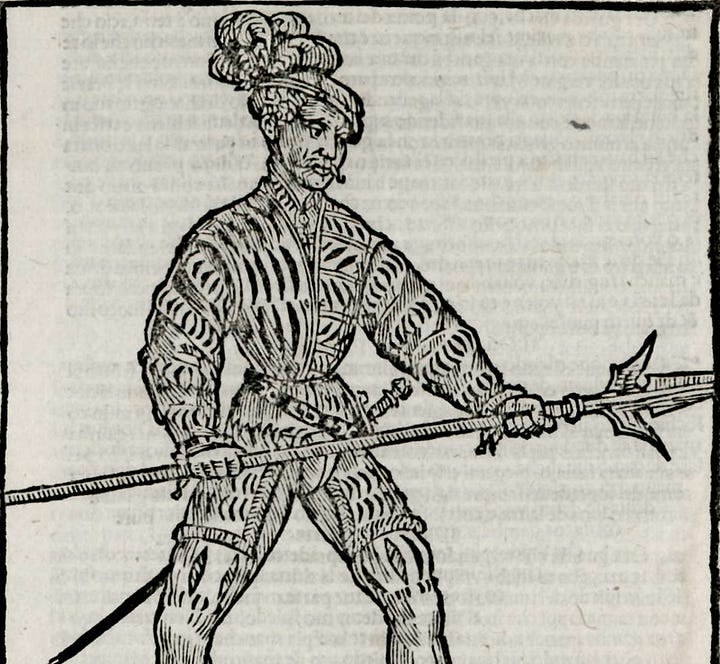

The spiedo is a broad-bladed spear with a pair of bat wings near the base of its head also known as a ranseur or corseque. The famous master Achille Marozzo includes an image of one in his Opera Nova, dated to 1536.

Now that we know what it is, the more interesting question is Why it is the way it is. What made someone decide that mounting a pair of bat wings on a spear was a good idea? Why was Maragilia of Perugia sleeping in John Paul’s bedchamber with a spiedo instead of a partisan or a pike or a poleaxe?

The Bolognese sources like Marozzo and Manciolino that discuss how to fight with these weapons do so in the context of using them in a one-on-one public duel with matched weapons. As such they do nothing to describe why spiedos exist at all or why anyone would use them in particular.

Fortunately, the Florentine fencing master Francesco Altoni provides some crucial detail about polearms. He declares that the partisan is “a fearsome weapon that calls for a man of great spirit and courage, because it has a large and heavy iron that requires great force…” Note the “iron” here refers to the metal head of the weapon.

Now here is Altoni’s description of the Spiedo, “The spiedo is a very useful weapon, because it has greater defense than any of the other polearms; its shaft is as long as that of the partisan and is held in almost the same way…”

In other words, Altoni considers the partisan an offensive weapon and a defensive weapon. In describing actions with the spiedo, Altoni emphasizes using the spiedo to trap the opponent’s weapon and then thrust them, generally after the opponent has attacked. As he explains, “With the spiedo the goal is to receive the enemy’s shaft with one of the wings, whichever of the two is prepared for it, and to then strike while also having control of the enemy’s weapon. In doing so you must always be prepared to trap the enemy’s weapon with your spiedo whenever he repositions his weapon. In this weapon and all others it is always suitable to first defeat the weapon and then the man…”

Matarazzo certainly knows all this and intended for his readers also to know that John Paul Baglioni was prepared for trouble and that is why his man has a weapon optimized to defend his lord. More importantly we can understand this now, too.

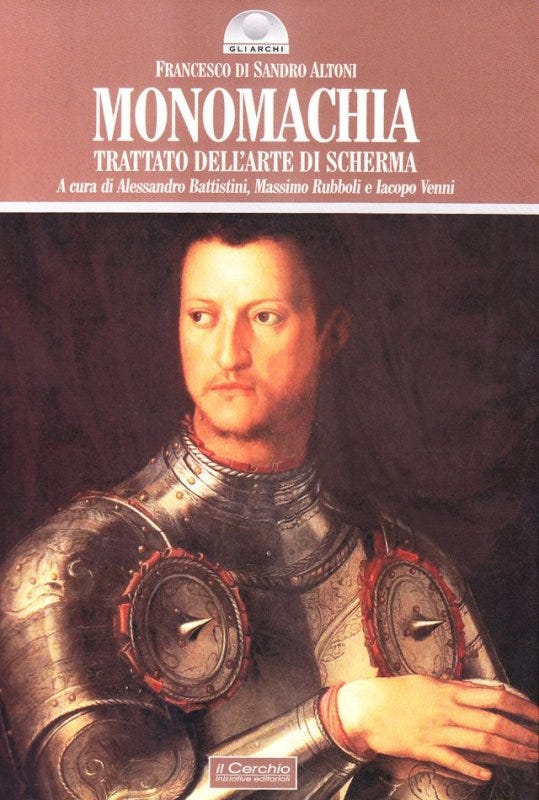

Francesco Altoni was the fencing master of Cosimo I, Duke of Florence, and he left us a manuscript of some Forty-Five chapters on fencing and the use of various weapons. His influence can be clearly seen in the works of Marco Docciolini. Suffice it to say we can consider him an expert on Renaissance Weapons. His full chapter on the use of the Spiedo is now available to subscribers of the The Art of Arms, HERE.