It’s impossible to quantify the impact of Gutenberg’s printing press on the trajectory of European civilization from its conception in the mid-fifteenth century to the present day. However, its initial expansion and dissemination throughout the continent wasn’t without casualty, and we can see the cut of its wake as it barreled through Italy during the life of Antonio Manciolino. It’s truly amazing how each of the characters adjacent to his narrative will play a part in the rising action, climax, and conclusion of this subplot brought about by the introduction of the technology. So to begin this journey it seemed best to address the knowns furthest from the epicenter of Manciolino’s life, his printers; Stephano Guillery and Niccolo Aristotile d’Rossi known as lo Zoppino, and to better understand the stories of his printers we have to first travel back to Mainz, Gutenberg’s print shop—1454.

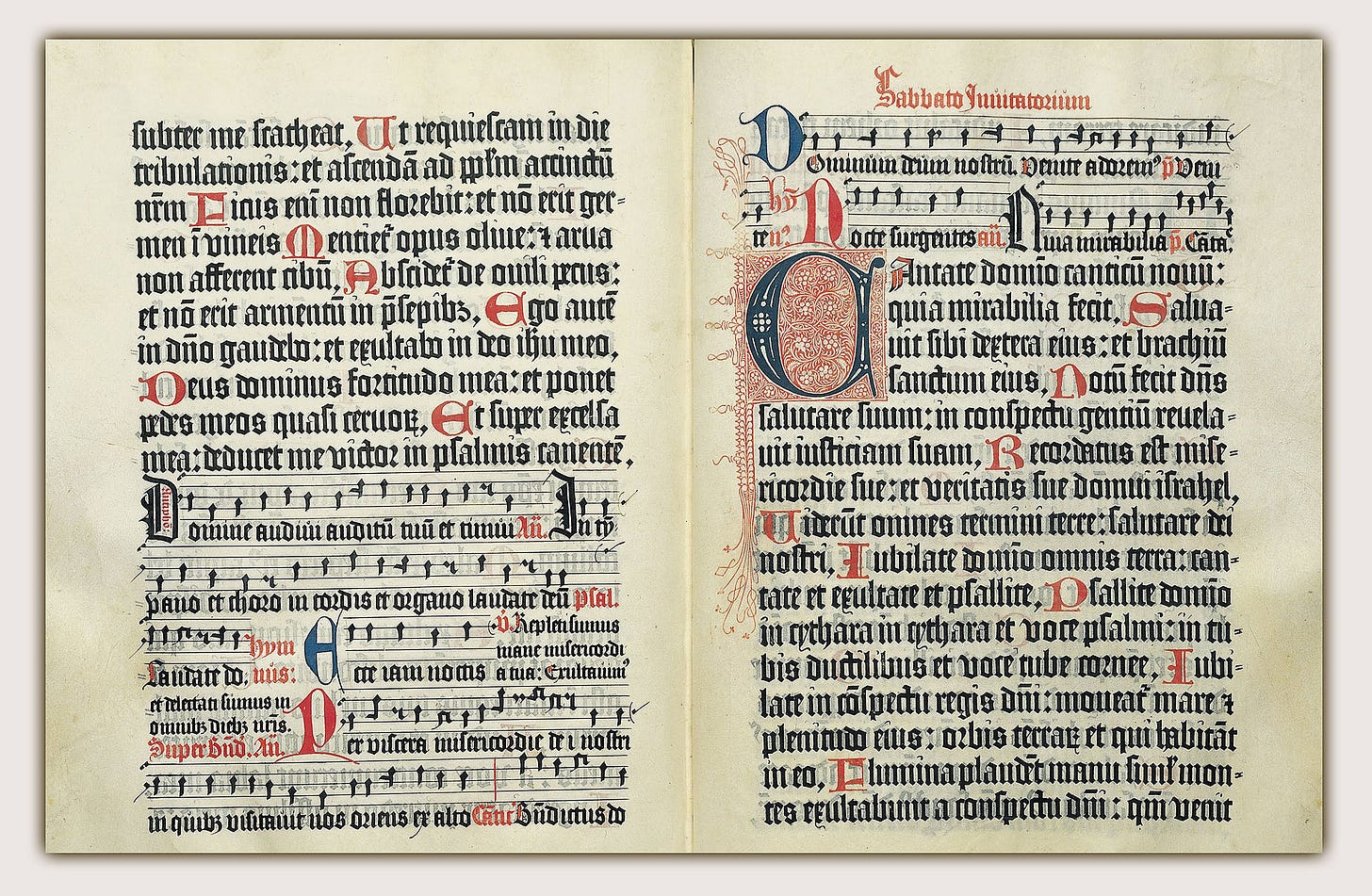

The realization of his innovations had barely set-in by the time that Johannes Gutenberg found himself stripped of all he had worked to achieve. Almost as soon as the first pages of his forty-six line bible left the press he was sued by his investor Johann Fust, and his trusted disciple Peter Shöffer, for the full sum of Fust’s investment of 1600 guilders, with interest, coming out to around 2200 guilders or $132,000 (US)[1], plus the intellectual license for the type of the bible, the rights to the Psalter that Gutenberg was working on for the Archbishop of Mainz, and a majority of his printing equipment. Many have argued whether this suit left Gutenberg destitute, however he certainly kept printing and was eventually afforded a stipend by the city of Mainz in his old age, so he wasn’t completely forgotten, but this story isn’t about Gutenberg necessarily, it’s more about Fust and Shöffer and the consequences of their actions, and how they changed the course of history.

After winning their case, Shöffer married Fust’s daughter and together they continued the publication of the Psalter that Gutenberg was lovingly working on. While Fust prided himself as a salesman, Shöffer was an artisan, and he kept the trade secrets that he’d learned from Gutenberg and the intellectual property they’d won from him in the lawsuit as closely guarded family secrets. The problem was, as their business expanded the necessity to hire skilled artisans outside of their circles of influence became an unavoidable risk. I know what you might be thinking, but it wasn’t a case of corporate espionage that would unleash Gutenberg's innovations on the world; it was the death of the Archbishop of Mainz, Dietrich Schenk von Erbach in 1459.

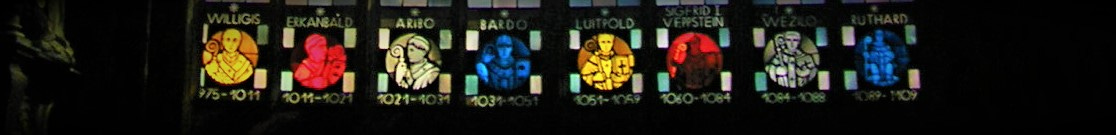

The city of Mainz was unique among the Imperial electorate, in that it was one of three ecclesiastical prince-electors in the Empire, along with Cologne and Trier, but was entirely unique in that it had been granted the right of self-governance in 1244[i], and its city council had a say in the election of its Archbishop. As an electorate Mainz also held powers of state second only to the Emperor, so it’s not surprising that Fust, Shöffer, and Gutenberg all played a part in the election process, and put the power of the printing press behind their preferred candidates. This was one of the first elections influenced by the widespread use of the printing press, and its effectiveness is evident in the outcome. The two candidates who ran for the position of Archbishop were Diether von Isenburg and Adolf von Nassau.

Diether was the Domkustos of the Mainz Cathedral, which basically means he was the interior decorator, bouncer, janitor, bell ringer and handyman for the entire facility; he’d been educated in the Church and was destined for an ecclesiastical life as the second son of a Count, after failing to become the Archbishop of Trier he took a job in Mainz and bided his time for the next Archbishop seat to become vacant. Diether had the backing of the people of Mainz, he had promised them that any reforms brought by the church would be presented to them, and that they would have a say in the final decision—he had Gutenberg’s vote. Naturally, this made Adolf of Nassau the favorite of the folks in power, Pope Pius II and the Emperor Frederick III; he had no ecclesiastical upbringing, just a title— he had the backing of characters like Fust and Shöffer, who during the election process would use their press to publish seven bulls and briefs issued by Pope Pius II in support of Adolf von Nassau[ii].

While Diether may have been educated in the church, he knew how politics worked and when the vote became deadlocked at four-four, he bought the decisive fifth vote for 20,000 guilders, or $1.2 million dollars US (He had apparently tried the same trick in Trier, and it didn’t payoff), and agreed to support Albrecht Achilles Elector of Margrave and Brandenburg against the Count Palatine, Fredrick I. The Pope and the Emperor were both enraged, and refused to confirm Diether’s position, but Diether put on the Mitre[iii] anyway, and threw himself a party.

Naturally, after this debacle, both the Pope and the Emperor tried everything they could to remove Diether from power, demanding that the election was fraudulent, that it was simony—that it was stolen, but Diether refused to budge. After Diether followed through on his promise to back Albrecht Achilles (the Emperor's guy) in the Palantine War, which ended in a decisive defeat at the battle of Pfeddersheim, the Emperor backed off, and after some convincing, the Pope finally relented. You see, the Pope had tried to throw a Crusade fundraiser in Mantua, and nobody showed up, so he decided to ‘leverage’ his friends to come to his party, and the person he had the most leverage against was Diether von Isenburg, so the Pope wrote to Dither and said, “look, come down to Mantua, pay the Papal annates, donate some money to my crusade fundraiser, and I’ll tell you you’re a real Bishop.”

According to the Papal records, and the Catholic encyclopedia Diether refused, alternative sources say Diether asked the people what they thought about the annates, a papal tax that was a “donation” of a years’ worth of tithes to the Diocese of Mainz given to the Pope upon the Bishops confirmation (20,550 Rhenish florins), and he asked the good people of Mainz how they felt about donating to a Crusade—naturally, they refused both. Where the records come back together is with Diether’s response, he told the Pope he wasn’t feeling well, and that he didn’t really have the money to pay the annates or donate to the crusade, so he was going to take it easy, and park his Cassock[iv] by the fire. The Pope responded with a minor excommunication. Undeterred, in February of 1461 Diether called a council in Nuremberg where he appealed that future council should abolish the annates tax, the Pope responded with a Papal Bull dated 21 August 1461, which fully excommunicated Diether, and replaced him with Adolf von Nassau.

Obviously, Adolf didn’t have any trouble getting the confirmation of the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, but this wasn’t the end for our dear friend Diether, as he wasn’t without his own powerful allies—or perhaps admirers—or just guys in the same ol’ sticky Holy-Roman Imperial situation. While Diether was playing power games with Pius, the Holy Roman Emperor was challenging the regency of one of his Dukes, Luis IX of Bavaria-Landshut (Luis “the rich”) in a messy German proxy war, that saw Luis and Fredrick I, the Count Palatine, join forces against Albrecht Achilles—the same guy Diether agreed to back in the Palatine war to get the decisive vote—in a conflict known as the Bavarian War of 1459-1463 (The same war where Paulus Kal cut his teeth as an Artillery commander for Luis the Rich, before becoming his fencing master later in life); like I said, messy. When Adolf von Nassau recommitted Mainz to the conflict, Fredrick I realized he had a powerful pawn contemplating his eternal damnation in Diether von Isenburg, so he agreed to prop Diether up for a few territories in the Mainz Diocese if Diether could rally the people of Mainz against Adolf. Diether said, “keine sorge”.

With Fredrick I, Count Palatine, down in Bavaria with Luis “the rich”, teaching Albrecht a thing or two about warfare, ol’Emperor Fredrick’s proxy war was starting to backfire, and he quickly realized that he stood to lose ground if he didn’t do something, so he stepped in and called a time out; he asked the boys to join him for a Bohemian vacation where they could discuss their differences, see the sights, and bring down the tension with a nice cool Pilsner. Louis accepted the invitation—the BoHo he was—but he let his armies keep up the attacking momentum in Albrecht’s lands while he was kicking it in Prague. This didn’t sit well with Adolf and his Swabian buddies, so they decided to go on a revenge tour; they’d realized that while the Bavarian lands weren’t in their purview, the Palatinate of Fredrick was ripe for the picking. Gathering a sizable army of 8,000 men in Bretten, they crossed the Rhine and marched up the west bank until they reached Speyer, then—because their appetite for loot and destruction was not yet satiated—they crossed the Rhine to the east bank, and started sacking their way up toward Seckenheim. Unbeknownst to them Fredrick wasn’t really keen on Prague, and decided to cut his Bohemian vacation short— that's when he heard the Swabians were knocking on his door. The Count Palatine and his army quick marched out of Bavaria and caught the rearguard Adolf’s army at Seckenheim, a surprise that was amplified by the fact the Swabian vanguard—full of Adolf and his cocksure Swabian cronies—were off their discipline and had drifted too far ahead of their army to engage Fredrick in a timely manner. By the time Adolf and his friends reached the forests of Seckenheim, Fredrick had already dispatched the bulk of their forces, and the bewildered lords were forced to surrender. The Margrave Charles I and his brother the Bishop of Metz were wounded and captured alongside Ulrich V of Württemberg and Adolf von Nassau.

With Adolf in chains, there was an urgent vacancy in the Diocese of Mainz, so Diether heroically stepped in and took his Mitre back. He gave the negotiated lands to Fredrick, and started working on the reforms he’d promised to the people of Mainz. Everyone in Mainz was happy, well—almost everyone. The problem with high profile prisoners is they eventually get ransomed, and when they do—a Luis might get Rich, but a Diether has to watch his Cassock. Sure enough, on 28th October 1462, a bunch of Adolf’s supporters met the disposed bishop at the gates (we can imagine Fust and Shöffer playing a part here), and let him into the city with his complement of 500 heavily armed men. Twelve hours of desperate fighting ensued, street-to-street, house-to-house. The people of Mainz rose up and tried to repel the invaders, but Adolf’s goons had the better of the citizens and their Militia, and took control of the city.

All told, over 400 people lay dead in the streets, and to add insult to injury, Adolf let his men sack the city—his city, as was custom. He didn’t stop there however, a few days later he called all of Diether’s loyal supporters to a council under the guise of reconciliation, 800 people showed up to hear him out, and instead of negotiating with the people he drove them from the city; they were permanently banished. Adolf wasn’t done however, the death nail had yet to be delivered, we can imagine Adolf asking Shöffer and Fust to print his grand declaration, to have it sent around the city with his men to drive into the door of every citizen; Mainz was no longer a free city, from this day forward it would it would be a vicedominus under the sole leadership and discretion of the Archbishop, of Adolf—the tyrant had won.

Among the 800 exiles fleeing Mainz was Johannes Gutenberg and many of the skilled artisans—guildsmen—who had all backed Diether, and lost. They made their way to new cities across Europe, settling in Paris, Milan, Rome, Bavaria, and beyond, and with them they carried the knowledge of Gutenberg’s press, his movable typeface, and his innovative inks; they also carried the scars and grievance for the political rot of the church that displaced them from their homes.

[1] Based off of estimated exchange of roughly $6000/100 Gulider: http://vanosnabrugge.org/docs/dutchmoney.htm

[i] Berthold Von Henneberg | German archbishop | Britannica

[ii] In, The Papacy Power and Print: The Publication of Papal Decrees in the First Fifty Years of Printing, by Margaret Meserve, she briefly discusses the Mianz diocesan feud, and provides the quantitative figure for the number of Bulls and decrees printed by Fust, Shöffer. The

[iii] Bishops hat

[iv] Bishops robe or cape