Bologna had escaped from the domination of Cesare Borgia and the Church but it still had to reckon with the Almighty. The city seemed to have distinctly earned God’s displeasure: He sent a lightning storm that destroyed many buildings in the city, including the tower over the Palazzo Bentivoglio.[1] Then after the lightning, there came a series a series of earthquakes that destroyed much of the portico on the outside of the Bentivoglio palace as well as scaring the people of the city. “People were so terrified that they no longer felt secure living in their homes and sought open spaces, sheltering under tents, wooden sheds, straw huts, barns, and other makeshift shelters made from cloth or blankets.”[2]

But these would prove to be but small irritations compared to the cold that God sent at Bologna. On November 25th of 1503 a terrible blizzard swept through Bologna and covered the fields around the city with snow as deep as five feet. The cold was so terrible that it, “claimed the lives of many travelers due to the harsh winds, and an infinite number of animals perished in the countryside… the cold destroyed fruit trees and other plants in gardens. The frost even caused stones, tiles on roofs, and stone columns to crack, and nearly all the vines perished.”

The deep snow lingered until the end of April, killing the wheat crop not just in Bologna but throughout the region. The fields of Emilia-Romagna were the breadbasket of Italy and the failure of the wheat crop that year, “with barely enough grain to sow,” foretold the coming of the third horseman of the Apocalypse, Famine.

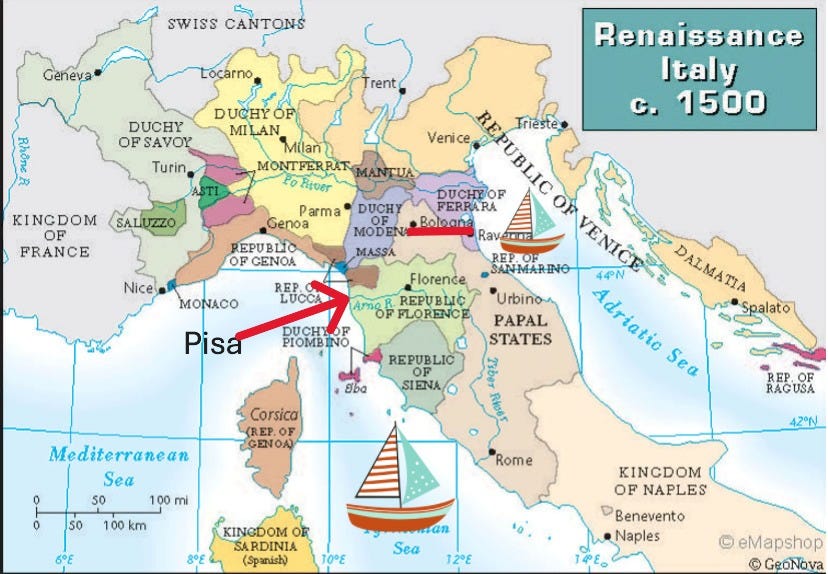

Commissioners from Bologna traveled to far off lands buying grain to import into the city. But Bologna was a landlocked territory; for centuries the Bolognese had tried to extend their territory to the Adriatic, they had even crushed a Venetian river fleet in 1271, as they groped their way to the sea.[3] But they never acquired a port. They now paid the price for that failure. Venice refused to allow grain going through the Adriatic to pass to Bologna and Florence did likewise.

Bologna would just have to starve.

Unable to bring food into the territory the poor were reduced to desperate straits to survive. “The poor, in Lent, having nothing else to eat, scavenged for the skins of salted eels; in times when meat was permitted, they consumed blood from the slaughterhouse. Many peasants survived on salted herbs and bread made from ground acorns, and many died from deprivation.”[4]

Here was a potent demonstration of the maxim, “He who commands the sea, commands everything.”[5]

Cities with access to the sea like Florence still had enough food, enough food in fact to fight a war. In 1504 Florence decided to renew its war with Pisa. To lead this army Florence tapped another one of the uncles of Guido Rangoni. This was an experienced condottiere named Hercules Bentivoglio. This Hercules was a son of Grandma Bentivoglio by a previous marriage and had grown up in Florence rather than Bologna. For a long time there had been tension in the family between he and Hannibal Bentivoglio, since Hannibal was the heir apparent to Bologna.

But relations between Hercules and Hannibal were now good. Hercules recruited Uncle Hannibal to lead a force of 70 men-at-arms and 40 light cavalry in his war against Pisa.[6] Hannibal would be fighting alongside one of the great warriors of the era, the famous master of arms, Pietro Monte.

Guido Rangoni wanted to go with his uncles to fight against Pisa and build his reputation, but his duties on behalf of Grandpa Bentivoglio kept him in Bologna. Guido could only look on with envy as Hannibal’s company of Bolognese left the city wearing “French-style armor with a falcon crest emerging from its nest and bearing Hannibal’s personal motto, ‘My Time.’[7]

Instead of covering his name with glory, Guido Rangoni was kept busy with the mundane tasks of running a company of men-at-arms. Guido’s company consisted of 100 lances and each lance had three men: a knight, an armed squire and a page.[8] Much of his time was spent on the mundane tasks of reviewing his men and keeping up on the finances of his company — tedium that mad a hot-blooded young man long for the heart-pounding action of war.

Hugo Pepoli would be getting all the heart-pounding action he could wish for.

The Bentivoglio were not the only family being recruited into this war. Pisa was desperate for soldiers to stave off Florence. Seeing the opportunity to grow the family fortune and reputation, the Pepoli family offered to raise a company of 100 infantry from among the Bolognese mountain men. Pisa gladly took them up on the offer.

Romeo Pepoli, Hugo’s elder brother, was the captain in charge of the company. Hugo helped him to organize the unit, making sure the men were competent to use their weapons. As Pisa was recruiting men to defend the city against assault, this infantry company was armed primarily with the weapons most useful in defending a breach of the walls, close quarters weapons like the shield and sword or cut and thrust polearms like the partisan and billhook.[10]

Then they had to find a way to get to Pisa.

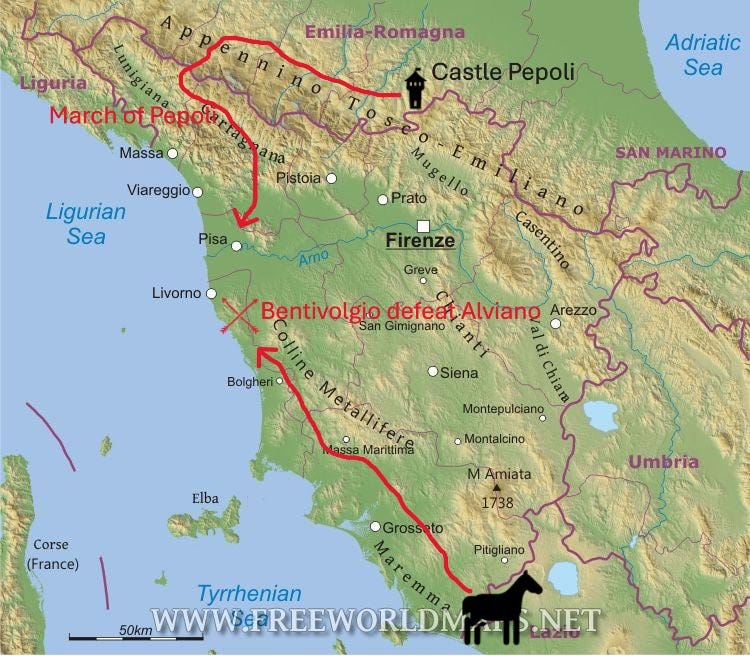

Florence had blocked the mountain passes into Tuscany and Grandpa Bentivoglio would not allow the Pepoli to pass through Bologna to get around the Florentines, since he was allied with Florence. The Pepoli were forced to lead their men on a difficult and circuitous march along mule tracks through a country with no food to be had. Famine had, “intensified to the point that there was nothing to eat, and cries and laments were heard everywhere.”

While carrying heavy gear up and down the narrow roads on legs made weak by hunger and leading half-starved mules, the Pepolis’ men found a way to cross through the mountains into Tuscany around Lucca and thence made their way to Pisa.[11] Here there was an adequate if not abundant supply of food.

Hercules Bentivoglio was doing his best to reduce the amount of food that came into Pisa by employing cavalry to break the city’s connection. But the Pisans were a special breed: stubborn, experienced in war, and determined to remain free.[12]

A relief force approached from around Rome that looked to break up the attack on Pisa and open the connection to the sea so that Pisa could get more than just the thin trickle of food that was making it past Florentine patrols. The commander of this force was the general under whom Guido and Hugo Pepoli would late serve, one of the great condottieri of his age, named Bart Alviano.

Hercules Bentivoglio deployed uncle Hannibal and the Florentine army to keep Alviano from reaching Pisa. He cleverly outmaneuvered Alviano and then attacked. At the crucial moment of the battle uncle Hannibal convinced Mancino da Bologna to switch sides.[14] This caused Alviano’s forces to collapse. General Alviano was then forced to flee, riding away with nothing but a few quick horses and two wounds to his face.[15]

Pisa and Hugo Pepoli were now on their own.

Florence now saw it could push for a more decisive result than starving Pisa would produce. They had the strength to assault Pisa and capture it.

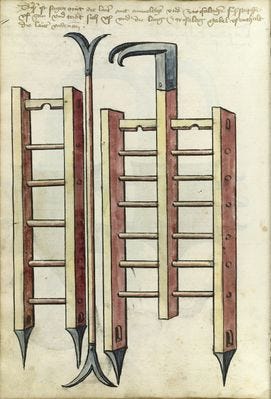

Florence would have only a short time for making good their conquest, for once the autumn rains began the area around Pisa would turn into a pestilential swamp.[16] Niccolo Macchiavelli and the rest of the Florentine government went into frenzied preparations, raising 400,000 ducats, levying infantry, finding artillery and powder, incendiary devices, securing large amounts of wood in order to make scaling ladders, getting shovels, hoes and billhooks for the pioneers, etc..[17]

Inside Pisa preparations for the siege went on with an equal frenzy. They had survived a combined attack by Florence and France in 1499 through determination and they were equally determined to hold onto their independence now.

On the day of the Madonna in September the Florentines unleashed their cannons on the walls of Pisa. The cannons roared from sunrise on for a whole day, blazing away for twenty one hours. Under such a bombardment the walls of Pisa crumbled, to that by two the next morning, about 50 feet (18m) of wall had been turned into so much waste rubble.[18]

Pietro Monte now led 3,000 Florentine infantry towards the walls while thousands more waited to exploit the assault. In the breach flew the yellow banners of Spain, waving in the breeze where the Spanish infantry was surging forward.[19] On the intact walls beside the breach waved the silver and black checkerboard banner of House Pepoli. Here the Bolognese infantry awaited the attack of the Florentine infantry.

As the Florentines drew closer the thwack-thwack-thwack of shooting crossbows from the walls of Pisa filled the air. Against the closely-packed ranks of charging infantry, the shots of the Pisans could hardly miss. Hugo Pepoli directed the few crossbowmen in his company to shoot at the enemy soldiers carrying scaling ladders towards the walls.[20] The Florentines had plenty of crossbowmen of their own and bolts began to fill the air around the parapets of Pisa.

When the Florentine wave broke upon the ranks of Spaniards in the breach then the battle was well and truly joined.

Hugo’s battle now centered on the scaling ladders being thrown up against the walls. These ladders had sharped hooks that gripped to the brick walls all around Hugo. For ordinary men these were dangerous to dislodge with their hands, though with his gauntlets Hugo had a better chance. But as they tried to shake the ladder hooks off the walls, Florentine crossbowmen peppered them with quarrels. Still, Hugo and his men were able to keep the Florentines off the wall for now.

The Florentines brought up gunners and more crossbowmen to make the job harder. Now Hugo had cause for great fear as two-pound cannon balls whizzed through the air around him, threatening death. Even when the Florentine gunners missed the men, the fire of their guns shredded the brick walls and sent shards of clay flying every which way, shredding and blinding men.

Backed by all this support a small party of Florentines did establish a position on the ramparts, but were quickly overwhelmed by the Pisans and the Bolognese under the silver and black.[21]

Down in the breach Pietro Monte led his Florentines to fight against the Spanish. But the Spanish soldiers were not to be broken, and the Florentines could hardly make their numerical advantage manifest within the tight confines of the breach. Like the 300 Spartans at Thermopopyale, these 300 Spanish were immoveable against any odds so long as their flanks were secure.

With the flanks guarded by stubborn Pisans on one side and “bold mountain fighters” from Bologna, Pietro Monte’s men were unable to get through the Spaniards.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Pietro Monte ordered his trumpeter to blow retreat and the Florentines fled the fight leaving dozens of dead and dying on the field. A great cheer went up from the men on the walls.

This cheer that was brought to an immediate stop by the deep thump of a Florentine siege cannon.

Hercules Bentivoglio and the Florentines now planned to a new attack. Since the size of the breach had been too small on the previous assault, they now spent three days blasting away at the walls of Pisa. This they hoped would created a large enough breach where they could bring the weight of their superior numbers to bear. Over the next three days the Florentine artillery brought down as much as 250 feet of wall.[22] But the Pisans were not so easily demurred.

Pisan men and women took advantage of the region’s thick soil to build a strong earthen rampart in front of their broken walls, an earthen rampart that was largely resistant to the blasts of the Florentine artillery.[23] Behind this rampart the Spanish and the Pisans now arranged themselves with firearms and crossbows.

With that section of the city under the guard of the Pisans, Hugo went with his company to defend the bridge connecting the two halves of the city.

The Florentines now committed all their troops to a new attack. Hercules Bentivoglio divided his troops into three different divisions. He sent his first division once again under Pietro Monte to create a breach at the area where the walls had been destroyed.

The Florentines went forward as ordered. But the Pisans were ready. “At the loud peal of a bell the men in the trenches left their stations and their womenfolk came forward also with crossbows and firearms, these they now fired on at the hesitant Florentine infantry.[24] After the losses three days before, the morale of the Florentine levies was spent and they took to to the ground for cover. Pietro Monte and the other commanders urged them forward, but the Florentine forces, especially the hastily-recruited militia of Florence, refused to move forward against this deadly hail of lead and crossbow bolt.[25] The Florentines tried to direct their own fire against the Pisans, to try and intimidate them into running back behind the cover of their walls, but the Pisans were as fearless and obdurate as stone.

To get the infantry moving forward, Pietro Monte personally came forward and charged with a group of men-at-arms directly at the breach. His example did little to hearten the infantry.

Hercules Bentivoglio then sent up a second group of infantry, but these also failed to charge the breach, even though the commanders of this unit descended into the ditch at the foot of the walls to lead them by example.

The Florentine commissioner charged with commanding the army tried a different tack with the infantry. Instead of urging them forward by inspiration he fell back on fear. He rode amongst the cowering men, striking about, wounding some and killing others. He managed to get them moving reluctantly forward, even as cannon fire from Pisa ripped lanes of death through their ranks.

All the hopes of the Florentines and Hercules Bentivoglio now centered on capturing the bridge where Hugo and the rest of Romeo’s company was stationed. This third division of the Florentine army moved in boats and along the quays of the Arno River.[26] Since the Pisans had concentrated their their artillery and gunners around the area of the breach, this force was able to proceed into the city. They were hemmed in by walls from above, and crossbowmen took a heavy tariff of their numbers, but this force was still bold enough to make it to the bridge.

Upon reaching the bridge, the boats stopped and the men traveling on the quays clambered upward. Hugo Pepoli’s men here crossed swords with the attacker, thrusting and slashing against the superior enemy until the bridge was slick with blood and it became a battle just to keep standing upright.

Word spread of this fight throughout Pisa and reinforcements came running to bolster the Pepoli forces on the bridge. The Florentines were forced to retreat.[27]

All out of courage the Florentine infantry, “withdrew to their encampments, achieving nothing but bringing infamy upon Italian soldiers throughout Europe.”

But this infamy that did not apply to Hugo Pepoli and Romeo’s company of mountain men. They returned to Bologna covered in glory.

Follow the adventures of Hugo and Guido in our next episode, Into the Fire

[1] Ghiradacci, p.330

[2] Ghiradacci, p.334

[3] Bologna, città marinara 1270-1273. S. Nesi. 2008.

[4] Ghiradacci, p.335.

[5] From Letters to Atticus, Cicero.

[6] Ghiradacci, p. 336.

[7] Storia Fiorentine by Francesco Guiccardini, p. 273. Also Ghiradacci p. 337. The Latin is “nunc mihi,” meaning “Now for me.” This has been translated in a way to convey the feeling of a motto. Also it’s only a guess that Guido wished to accompany his family.

[8] This is an educated guess. See Military Organization of a Renaissance State by Mallett & Hale pp. 70-71 for more detail. In the period 1490 the Venetian lance consisted of four men. It is possible that a Bolognese lance consisted also of four men (including a mounted crossbowman), but it is more likely that Bologna’s mounted crossbowmen served in separate companies, especially in light of Bologna’s more limited resources. This is a topic needing further research.

[9] See Mercenaries & their Masters by Michael Mallett.

[10] This is suppositional. What we do know is that all Italian cities had plenty of citizens equipped with firearms and crossbows for defending the walls. We also know that the mountain men of Bologna had a reputation for fighting in the field. For this reason the most logical usage of the company was for melee combat. As we will see later, the Bolognese field armies were equipped with a broad variety of weapon, and the Bolognese manuals on polearms provide for the use of the partisan, pike, and billhook, among other weapons. Also generally in the field long weapons like the pike are more useful, especially where one must fight horsemen. In the tighter quarters of a siege fight where the enemy is primarily other infantry shorter weapons are more useful. Also note that Romeo might have been a cousin instead of a brother.

[11] See www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Piero Gambacorta.” In later 1504, he “escorting the relief forces arriving by sea and land from La Spezia, Genoa and Lucca.”

[12] Storia Fiorentina, Guicciardini, 280

[13] Storia Fiorentina, Guicciardini, p. 279. Giovio, p.183.

[14] The precise details of this are unclear. But Sanuto describes Mancino’s behavior in this battle as “the cause for Alviano’s defeat.” Furthermore he and his company of 200 men switch sides after the battle (see www.condottieridiventura.it entry for Mancino da Bologna, August 1505.

[15] The whole fight is best described in the account given by Giovio on p. 184 in his “Istorie del Suo Tempo.”

[16] Storia d’Italia, p.603

[17] Scritti Inediti, Macchiavelli, pp. 205-224

[18] Giovio, p. 605.

[19] www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Pietro del Monte da Santa Maria,” for September 1505.

[20] Note the presence of men using scaling ladders is not directly attested in the historical sources. But we do know that the Florentine went to great effort to get wood for ladders and that it is highly unlikely that the Florentines would try to break through a breach only 50 feet wide with 3,000 men.

[21] This part is suppositional, simply trying to provide a best guess of what the fight would have looked liked given the information available. This initial skirmish is described in Storia d’Italia, pp.604-605. Storia Fiorentina, and also in Giovio, p.183 and in the most details on www.condottieridiventura.it under “Ercole Bentivoglio,” for September 1505.

[22] Vita di Antonio Giacomini, Jacopo Nardi. pp.147-148.

[23] Macchiavelli, Art of War.

[24] Sanuto, col. 238.

[25] Gucciardini, “The following morning, to open up a larger section of the wall, another battery was set up nearby, leaving between the two bombardment points a section of the wall previously attacked by the French. When enough of the wall seemed to be down, Ercole ordered the infantry, already arrayed for battle, to launch a vigorous assault on both breached sections. However, the Pisans, with the women as determined as the men, had, during the bombardment, constructed a barricade with a trench in front of it.

[26] This group was commanded by Zitolo da Perugia whom we will focus on during the Siege of Padua in 1509.

[27] www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Ercole Bentivoglio,” dated Sept 1505. Note that where in the battle Hugo’s company was servig was unclear. But with the men and women of Pisa focused around the area of the breach where they could also be building up an earthen rampart to support their city, it would have been logical to send Pepoli’s company to guard the bridge. But ultimately this can be nothing more than an educated guess.