Studying the Birth of the Liechtenauer Tradition

Part 1 – The Scope and the Methodology

Introduction

This is the first guest article in a short series where I shed some light on the birth of the first widespread fencing tradition that spans over 350 years from the last decades of late medieval well into covering most of the early modern era. Yes, it’s called the Liechtenauer tradition, and you already know about it from the fight books. But probably not like the way I will be handling the subject. And let’s not get too hung up on the name of the tradition just yet!

Whereas my later articles will go into the details on sources, this one outlines the scope of the research, discusses the methodology and my reasons for choosing them. My plan for the last essay of the series is to look at the impact of all these findings on the fencing tradition itself. Even though this first part won’t go into the sources yet, as a major teaser, I will include a longish excerpt for your enjoyment so you get to see how exciting some of the historical accounts can be. Sometimes the historical research is cool, and the rest 90% of the time you are just wishing that it was.

The Methods

When studying the history of the phenomenon like a martial art tradition, it’s useful to take different points of view to get a better understanding of it. Comparing different research angles makes it possible to evaluate the relevance of each finding and helps us connect events and people together for a robust overview of the subject.

The nature of a martial art tradition draws our attention to the origin stories and legends around it. But there is also the consideration that once the Liechtenauer lineage got started, it remained relatively unchanged for a while. This means that after the people with personal connections to the early days of the fencing style were not there anymore, it’s very likely that the corpus wasn’t really questioned that much. From such a point onward it becomes difficult to assess the underlying ideas that originally shaped the martial art into the form where it later got known to the wider society of the time. This means there is also a very practical point in keeping to the first decades of the tradition in order to understand its nuts and bolts. In effect, this means studying roughly the first quarter of the 15th century since that is the period before the fencing books start appearing.

If we only study society and politics of the period – or in other words if we only consider the broader historical phenomena – we might fail to notice what is concrete and relevant for the research subject. To address this, I will also take a narrower point of view to study the personal history of select individuals that seemed to be influential around the time. This kind of biographical research is a useful tool in the study of history, since it ties events together into a single (though incoherent) arc that cuts into speculation that would otherwise accompany us if we only took the bird’s eye view of the larger scope of the society.

The larger picture of the society will then give useful context to the personal histories, while the personal histories will give some concrete examples of what actually was going on. The biographical study will also link surprising places and people together under the same scope. Hopefully it will make sense to you. This method of combining bits and pieces will give a better background for understanding for the fencing tradition, nothing more. But nothing less, either.

I don’t necessarily get all that hung up on what’s the most relevant bit in relation to some other morsel of information regarding the people and the phenomena. Just writing the findings down makes it possible to re-evaluate certain details, develop the ideas further through new studies. Sometimes it also means trashing already written bits of the narrative altogether and starting anew. This way of writing about history is a central tool in exploring the subject. This is the kind of revisioning I had to do a few times along the years when a train of thought or a trail of documents didn’t lead me anywhere. So also the things I am going to write about here in this blog might still change in the light of better propositions.

The Scope

The purpose of the research is to provide context for the emergence of the so-called German fencing tradition. We can divide the era when this school of fencing rose to prominence into three parts, as is often customary in historical research. The first part is the time of Liechtenauer and the time of his closest students. This would be the point when Liechtenauer would have been travelling around Europe and partaking in fencing with foreign masters, as is claimed in the early fight books. The second part would be the time of the other masters of the tradition and their closest students, which would encompass the ‘Gesellschaft Liechtenauers’ properly and fully. It would be when Liechtenauer had formed an idea of a fencing style and was gathering like-minded individuals to synthesize a common framework and further learn from each other. The third part is the time of the glossators and the time of the fencing books.

We mostly know of these people through the fencing books. Outliers aside, they early period Liechtenauer fightbooks have been dated from the middle of the 15th century onwards in increasing amounts all the way to the end of the century, and then the number of volumes per year starts to drop. This represents the third generation in the three-part division, which would date the second generation in the middle of the century. There is some debate as to when the first generation would have been active - I assume that something of notice must have happened towards the end of the first quarter of 15th century, which would be the time that gave rise to the members of the gesellschaft. This assumption is of high level of confidence and it only assumes the transfer of skill through personal contact from one generation to the next.

Focusing the efforts on the first quarter of the century is a logical choice if we want to have information of the society that gave birth to the tradition we can later see through the fight books. Detailed information of this period is missing from the treatises, so we need to examine the phenomena of that era on a broad scale to scan for bits of relevant information. It’s also a good idea not to hold on to hagiographic creation stories and richly colored details, which sometimes can be seen in the origin stories of various martial arts.

Although the German fencing tradition of the time is called the Liechtenauer school, in practice, it encompasses a broader family of various fencing schools that came to light after the Liechtenauer school started spreading. Besides the common Germanic corpus, these different martial schools are united by the tradition of mixing a rhyming verse (zedel, zettel) and a verbose explanatory text (glossa), they seem to be documented on paper, they often share a bit of an eclectic approach to practicing fencing with different weapons, and the use of physical virtues as teaching tools instead of a strict theoretical fencing framework.

To understand the phenomenon's emergence, we must examine society, politics, and violent encounters at the time just before the teachers of the school transcribed their texts. Even though my initial focus was on the first quarter of the 15th century, it is useful to briefly go through important events of the preceding decades and to observe how the society was evolving as these developments take a bit longer time.

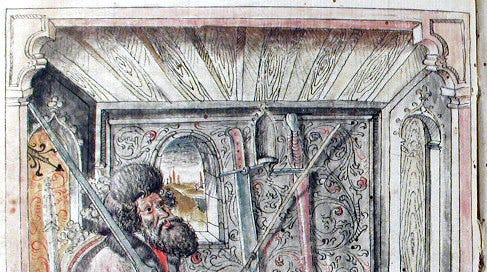

My research is mainly confined to the Nuremberg area. The reason is simply because some form of limitation helps to get us started and assists in selecting certain individuals whose activities we can follow for biographical research. As a result of the activities of these, the regional scope expands slightly. In this case, the study meanders and takes us to Venice, to the Hussite Wars, and to the Holy Land. It tells the story of complex relationships, the pursuit of nobility, the narrative of the ‘ritterliche kunst’, and the tale of backstabbing and betrayal. In other words, it will be a short story of the Liechtenauers. It may be only a story, but hopefully it also proves to be useful as we try to understand the birth of the German fencing traditions.

And Finally

I have gathered anecdotes and details that all in turn try to provide context and possible explanations for the birth of the phenomenon. Some of these shed light on history pretty unequivocally. However, some findings are clearly more of a conjecture and serve as interim results for those who want to dig into the history from these perspectives. I have come to the conclusion that some facets of this research have not been thoroughly examined in historical research since the 19th century, and they might be kind of new opening contributions. If you want to go deeper yourself, the German research literature tends to be more comprehensive in these matters than English research literature. As an example of the 19th century summaries, I have included an excerpt from the history of Nuremberg during the end of the Hussite Wars.