It was time to party in Bologna.[1]

Hugo Pepoli and other Bolognese soldiers had driven off Guido Rangoni and the Bentivoglio and scattered them like hunted animals.

In the wake of their flight, the Pope’s governor called for revelry—a citywide celebration of victory. But for some men, wine, and feasting could never be enough. For many, this triumph was as unfinished as it was hollow. And for none was this more true than for Hercules Marescotti.

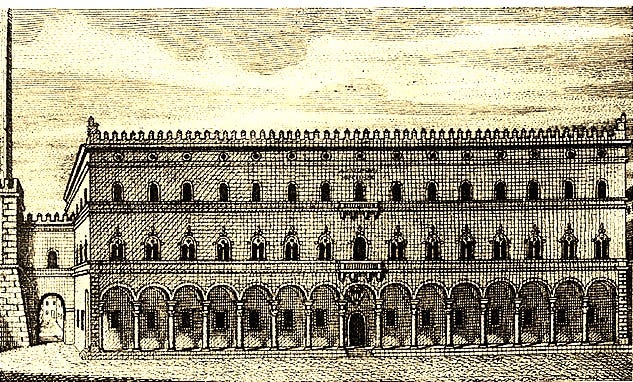

He had suffered too much. Exile. The slaughter of his kin. Now Hercules yearned to see the heads of Hannibal and Hermes Bentivoglio on a spike. But they were beyond his reach. His anger was so strong that it could not be contained. He focused his rage on the next best target: their house. The Palazzo Bentivoglio, a jewel of Bologna, stood as a taunting relic of their power. As the Venetian diarist Marino Sanuto described it, it was “one of the most beautiful in all of Italy.”[2] Hercules meant to make it a heap of rubble.

With the blessing of Bologna’s Papal authorities, he gathered two hundred men. Torches smoked in their fists, their horses stamped against the cobbled streets, and among them, Hercules rode at the front, holding aloft a torch drenched in pitch. The mob followed with “bundles of wood, crowbars, and similar tools.”[3]

But as they approached the grand palazzo, a lone figure stood in their path—Lucius Malvezzi, commander of the Pope’s forces. A man who understood Marescotti’s agony better than most, for the Bentivoglio had slaughtered his family too. He had been hounded, exiled, humiliated, his very livelihood stripped away by their influence. But here was the difference: Hercules Marescotti thought himself a warrior; Lucius Malvezzi was one. He had lived twenty-five years with war as his trade and Marescotti had not.[4]

Malvezzi stepped forward and raised a hand. “Do not commit such a terrible deed,” he implored. “A courageous man fights his enemy with arms in hand—he does not attack stones with a crowbar.”

A sneer curled on Hercules’ lips. His men stiffened at the insult, their grip tightening on their weapons.

“This palace is an ornament to our city,” Malvezzi pressed on. “Remember, I beg you, that the Bentivoglio never did such a thing to us. When we returned from exile, we found our homes intact, even made more beautiful than before.”[5]

But Malvezzi might as well have whispered into a storm. The words died in the roaring tempest within Hercules Marescotti—a tempest that now broke loose.

He spurred his horse past Malvezzi, and his men swarmed after him. They crashed into the Palazzo Bentivoglio, a tidal wave of flaming rage. Hercules, first to the building’s edge, thrust his torch forward, the flames licking greedily at the structure.

“Do your worst!” he bellowed.

His son, Emilio Marescotti—student of the great maestro di maestri Achille Marozzo—followed close behind, his torch setting another blaze.[6]

“Some climbed onto the roofs, hurling down tiles to expose the wooden beams; others swarmed the gardens, uprooting trees and smashing the statues of the fountains. Some laid their fury upon the strong, proud tower, wrenching its foundations apart; others turned their malice upon the magnificent paintings, masterpieces crafted by the most skilled hands.”

Here was the Renaissance in all its contradiction. The same hands that sculpted the finest marble, that painted the most delicate frescoes, were just as capable of swinging axes to annihilate them.

The destruction was relentless. The poor, drawn by greed, hacked at the very walls, prying free chains, vaults, and iron reinforcements. But their hunger for plunder brought death upon them—sections of the great palazzo collapsed, crushing dozens in an avalanche of stone and mortar.[7] The city did not weep for them. “If you live by looting,” they said, “you will die by looting.”[8]

By the time the fire burned low, the grand Palazzo Bentivoglio was nothing but rubble. Its statues smashed, its frescoes turned to dust. And yet, amidst the ruin, something remained.

In one of the rooms, untouched by crowbars and torches, a single painting had survived—a portrait of the Virgin Mary, painted onto the wall. The mob had stayed their hands out of reverence. But later, peasants from the countryside, greedy for whatever remained, came upon the image and struck it with iron pickaxes.

The wall groaned and collapsed upon them. Yet when the dust settled, they stood unharmed.

A woman and her daughter, witnessing the scene, cried out—there were tears in the Madonna’s painted eyes.

Word of the miracle swept through the city. Crowds gathered to see the weeping Virgin. The same peasants who had tried to destroy her now prostrated themselves before the image. They lifted it with reverence and bore it away, placing it upon the altar of the Bentivoglio church.

And in the days that followed, the faithful came in droves, whispering prayers before the Madonna. They spoke of wishes granted, of petitions answered.[9]

The Bentivoglio were gone. Their house lay in ruin. But they lived on in Bologna through the silent gaze of a Virgin who wept for all that had been lost.

Long Way To The Bottom

Word of the palace’s destruction spread faster than wildfire. In Milan, Grandpa Bentivoglio sat in prison, a once-proud patriarch no longer living in a marble house but instead in a rusty cell, the caged relic of a fallen dynasty. He had counseled against the doomed assault on Bologna, but his foolish wife and sons had staked everything on the desperate gamble. Now he poured his fury into ink, telling Grandma just what he thought of her and her stupidity.

His letter to Grandma Bentivoglio was as dangerous as a dagger and pierced as deep as any poignard.

“Look what has happened to you, foolish Ginevra [Grandma]. You chose to disregard the advice of wise men and follow your own passion. Now you and those with you have fallen into the grip of every misfortune. Because of you, I am in prison… and how do our children fare, led by your imprudent counsel? Banished from their homeland, cast out from Ferrara, shamed before the entire world. But what wounds my heart most is this: our palace in Bologna is in ruins. And of all these evils, you, woman, are the cause. These are the fruits of your reckless ambition. Find peace as best you can. Farewell."[1]

The words struck her like a blow. The grief that had gnawed at her since the destruction of the palace now pinched like a vice, crushing the last breath from her body. She collapsed onto her bed, and she did not rise again.

A year before, Ginevra Bentivoglio had been among the most powerful women in Italy—a patroness of artists and writers, a woman whose very name had commanded reverence. Now, she was nothing. Her death did not inspire mourning, nor did the Church grant her peace. The Pope, her enemy in life, denied her the sanctity of a proper burial. No tomb would bear her name. No candle would burn for her soul. Instead, her body was flung into a common pit, left to rot in eternity among beggars, drunks, and whores.

Such was the nature of fortune in the Renaissance. One moment, your name was spoken with fear and reverence; the next, fate struck you down like a guillotine, and all you had built was swept into oblivion. In Bologna, there were no tears for Grandma Bentivoglio. The city’s poets carved her epitaph in mockery, scrawling verses on walls that branded her as “greedy, grasping, horrible, terrible, and impious.”

And the ruin of the Palazzo Bentivoglio? That, too, was turned into poetry—gloating lines that mocked the fall of a house that once stood unchallenged.

As recorded by Ghirardacci, one such verse rang through the streets:

“I once was built from human blood and toil,

But soon I crumbled, ruined and spoilt.

Twice did Almighty God foretell my fall,

By quake and lightning, yet I cared not at all.

The third strike came from heaven’s wrathful sun:

The people, stirred by justice, to me did run,

With fury’s fire did they rise as one,

And so upon me, ruin swift begun.

Each hand did tear my walls, each claimed their share,

The marble stones they took, my strength laid bare.

All iron fell, was seized, and borne away,

And so, they named my fall Bentivoglio that day.”

Payback

The destruction of the Palazzo Bentivoglio had been met with cheers and laughter, but not everyone in Bologna reveled in its ruin. Beneath the jubilation, outrage smoldered. The Palazzo had been more than a house—it had been a symbol, a marvel of Bolognese craftsmanship, a monument to the city’s genius. Generations of artisans had poured their sweat into its gilded cornices, its frescoed halls, its soaring arches. Travelers had marveled at its beauty, and nobles had feasted beneath its painted ceilings.[1] And now, all of it—razed to nothing by Hercules Marescotti and his mob, while the papal government stood idly by.

To the city’s old aristocracy, this was sacrilege. Hugo Pepoli and his kin, members of Bologna’s ancient nobility, were aghast. And worse—Marescotti, flushed with his triumph, now saw himself as the ruler of the city. He and his family threatened anyone who dared oppose them, promising that their enemies would meet the same fate as the Bentivoglio palace.[2]

The air in Bologna grew thick with resentment.

Even Lucius Malvezzi, a sworn enemy of the Bentivoglio, found himself repulsed by what had been done. Disgusted by Marescotti’s tyranny and the Pope’s inaction, he turned his back on Bologna, departing to take service with Venice.[3] But others, who could not leave, began to conspire.

The man at the heart of this new conspiracy was a merchant named Casper Scappi. The destruction of the Palazzo had enraged him, but it was the miracle of the Madonna that steeled his resolve. If heaven had wept for the Bentivoglio, then it was clear to him—Marescotti and his ilk had to be punished. The only justice was an eye for an eye and a fire for a fire. The Marescotti would lose their own palace, just as they had stolen the Bentivoglio’s.

Scappi was no warrior, but he was a master of persuasion. One by one, he gathered like-minded men. They did not love the Bentivoglio, but they hated Marescotti more. Under the Bentivoglio, there had been order—under Marescotti, only threats and anarchy. Scappi even traveled to Mantua, seeking out Hannibal Bentivoglio himself. But Hannibal, hardened by exile, blew him off: “Without the backing of France, Venice, or Ferrara, you will fail.”

Scappi did not listen. He had waited long enough.

One night, he and his supporters took up their weapons and descended upon the Marescotti household. They came not as looters but as executioners. Hercules and his sons had terrorized Bologna, but in the face of death, their courage melted away. Like hunted rats, they scrambled onto the rooftops and fled into the night.

With their prey gone, Scappi’s men turned their vengeance on the Marescotti palace. A fresh mob visited their rage upon this edifice.[4] The fire that had consumed the Bentivoglio home now came for their enemies.

But Scappi was not finished. He rushed to the San Mamolo gate, hoping Hannibal would send forces to meet him. Messengers galloped to Ferrara, where Guido Rangoni, another exiled Bentivoglio ally, remained under the watchful eye of the Duke. “Come now,” they begged. “Bring Hannibal. Retake the city.”

Guido was stunned. Hannibal had told him nothing of this mad scheme. But he promised to send word.

Back in Bologna, Scappi struggled to hold the city. The papal governor rallied what forces he could, and Scappi shouted desperately to rouse the populace, “People, people!” But in Bologna, the mob and nobles alike had had their fill of revolution.

Except the Pepoli.

Hugo Pepoli and his brothers arrived with hundreds of armed men. They shared Scappi’s hatred for Marescotti, but they had no love for chaos. “A disorganized mess,” they sneered. Yet still, Hugo lingered, staying with a hundred men around the San Mamolo gate. He claimed it was to keep order, though it was clear he was waiting, watching—hoping the Bentivoglio would come to reclaim what had been lost.

Guido Rangoni himself arrived to witness the chaos firsthand. But like the Pepoli, he was unimpressed. He told Hannibal to steer clear of this fight.

With no army to back him, Scappi’s rebellion spiraled into pure anarchy. The mob, bloodied by its first taste of looting, turned its hunger elsewhere. They stormed the homes of Marescotti’s allies, ripping down doors, breaking through walls with “sacks and tools.”

But then, Hugo Pepoli made his choice.

When word reached him that the looters had gone too far, that they were attacking indiscriminately, he led his men into the streets. This was not justice. This was not what he had waited for. His soldiers struck down the thieves and scattered the rabble, shielding the Marescotti’s allies in their homes.

The tide had turned.

Scappi saw the writing on the wall. His rebellion had failed. The Bentivoglio were not coming.

And so, rather than die for a lost cause, he gathered his men and slipped out of Bologna, vanishing into the night—on his way to join the very family whose downfall had started it all.

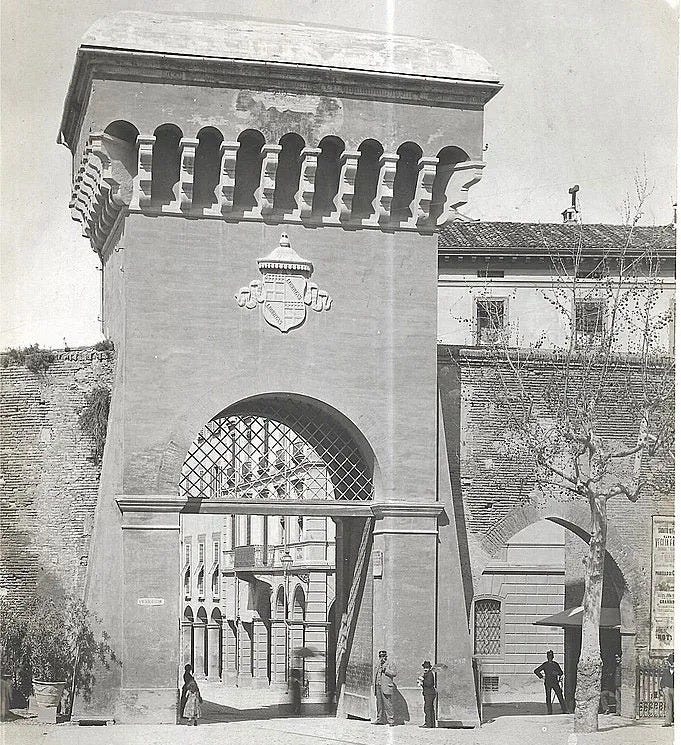

The Castel Sant’Angelo

In the aftermath of the revolt messengers rode hard for Rome, carrying news of Bologna’s upheaval. But when they arrived, the Pope declared he wanted to hear the truth of the event from the men who were there. He summoned Hugo Pepoli and other prominent nobles, assuring them they would be granted safe passage. “No harm shall come to you, in either person or property,” vowed the Pope.

Hugo obeyed. Others followed. After all, the Pope had issued a pardon for all those who had taken part in the riots—what reason was there to refuse?

Julius II let them linger in Rome for a few days, treating them with the civility of honored guests. Then, without warning, he had the entire group rounded up and thrown into the dungeons beneath Castel Sant’Angelo. Among them, foremost, was Hugo Pepoli.

But the Pope’s thirst for vengeance did not end there.

Guido Rangoni, still free, became the next target. Julius placed a bounty of four thousand ducats on his head—a fortune to any assassin bold enough to claim it. And as if that were not enough, he renewed the price on the heads of Rangoni’s uncles. There would be no peace for the Bentivoglio’s allies.

The Pope had decided that Bologna needed a new ruler—one who would put the fear of God into the city, one who would crush even the thought of rebellion. And so he sent a man who was, perhaps, the most despised clergyman in all of Italy.[1]

His name was Cardinal Francesco Alidosi.

Though a priest by title, there was nothing holy about him. He was ruthless, treacherous and a man devoid of scruples—and that was how his friends described him.

To his enemies, he was something far worse.

Alidosi wasted no time. He came not as a governor, but as an executioner. Anyone suspected of Bentivoglio loyalty was hunted down, strangled, and beheaded. One man, foolish enough to receive a benefice from the Pope that Alidosi himself desired, was killed for being in the Cardinal’s way. Even to speak well of the Bentivoglio in public became a crime; men who did so were executed and women who spoke well of them were publicly flogged.[2]

He was also not afraid of hanging his perceived enemies. Men were hanged just low enough that their toes barely scraped the ground. They would struggle for breath, suspended between life and death, for an entire day before finally succumbing—while the people could only look on in horror.

He imposed crushing fines on the people of Bologna, under the pretense of rebuilding the Palazzo Marescotti. But the money went not to stone or marble. It lined his own coffers.[3]

None of this was an accident.

Alidosi understood that Bologna had been free for too long. The people were defiant, independent-minded. They could not simply be ruled—they had to be broken. Where others might have followed Machiavelli’s dictum to allow a free city the illusion of its old government, Alidosi did the opposite. He stomped on their illusions, daring them to rise up.[4]

Because rebellion was exactly what he wanted.

He knew that Guido Rangoni and the Bentivoglio brothers would not stand idly by while their friends were strangled, their allies tortured, their people cowed into submission. They would have to act.

And the moment they did, Alidosi would be ready.

Because only when they stuck their necks out could he sever them from their shoulders—and mount their heads on the walls of Bologna.

Mission Impossible

The Pope turned a blind eye to Alidosi’s greed. Ruthless men required wealth to do ruthless work, and Julius II needed a strong hand in Bologna.

Meanwhile, war festered in the countryside. Bands of Bentivoglio loyalists took to the forests and hills, striking at their enemies where they could—raiding supply lines, ambushing isolated soldiers, and torching the homes of those who had betrayed them. In retaliation, Alidosi’s forces scoured the land with fire and steel, burning villages suspected of sheltering the rebels. The violence became so severe that even the French, always eager to meddle in Italy, offered to send their gendarmes to restore order. But the Pope and his allies knew better and refused.

The city seethed under Alidosi’s provocations, and in this pressure, a plan was born.

Alexander Pepoli, elder brother of the imprisoned Hugo, began conspiring with the exiled Bentivoglio. They understood that retaking Bologna was impossible, at least for now. But they could send a message. They could remind their enemies that Bologna still had teeth—that no man who had betrayed them could sleep soundly at night.

The plan was simple. They would slip into the city, strike down their greatest enemies, and vanish into the darkness before anyone could react.

They needed a leader. Guido Rangoni, still too young and untested, would not do. Nor could they risk the Bentivoglio brothers themselves. They needed someone else—someone bold, cunning, and utterly fearless.

As it happened, just such a man was between jobs.

His name was Mancino da Bologna—a battle-hardened infantry commander with a reputation for audacity and brilliance. He had recently led an assault against a heavily fortified German stronghold, and he had won. Now, he would lead the attack on Bologna. It was the kind of mission that could make his name immortal.[1]

Mancino set up his temporary headquarters in an inn on the Mantuan border, just beyond the reach of Papal forces. His conspirators slipped away from Bologna in secret, meeting him in the dead of night. They gathered in hushed voices, plotting their strike against Alidosi and his men.

But someone talked.

Word of the conspiracy reached Alidosi, and he reacted with swift, merciless precision. He dispatched his light cavalry under his best commander—the Lord of Mirandola—along with sixty mounted crossbowmen, with orders to capture or kill everyone inside the inn.

The first warning came when a sentry outside the inn cried out—only to have a crossbow bolt punch through his throat before he could finish his warning.

Then came the thunder of hooves.

The inn erupted into chaos as Mirandola’s men surrounded it. Half-drunk conspirators stumbled from their rooms, rushing for the doors and windows—only to be cut down by waiting crossbows.

And then Mancino stepped outside. Atop his head he wore his customary hat, with the sole of a lady’s slipper affixed to the front and bearing the word, “you” upon it. This was a bit of whimsy that he wore in honor of his beloved.[2]

He found the Lord of Mirandola already waiting for him, perched atop his horse in full armor, watching the slaughter unfold with the calm of a man who had seen it all before.

We do not know exactly what passed between them. But knowing the men, we can imagine it went something like this:

Mirandola, in a measured tone, said, “We don’t want you, Mancino. We only want Hannibal and Hermes Bentivoglio.”

Mancino smirked. “Funny. Hannibal was looking for you the other day.”

Mirandola raised a brow. “Is he finally ready to turn himself in?”

“No. But he said you should kiss your son goodnight the next time you go home.”

That was the moment Mancino charged at Lord Mirandola.

It was madness—Mirandola was on horseback, fully armored, surrounded by his men. But Mancino had a trick.[3] If he could close the distance, if he could blind the horse, if he could unseat Mirandola before his men could react, then maybe—just maybe—he had a chance.

As Mirandola’s mount thundered toward him, and Mirandola raised his sword fight, Mancino ripped the cloak from his shoulder and prepared for his maneuver.

The moment Mirandola began his downward swing, Mancino leapt across the path of the charging horse and pressed a cloak over its eyes.

But fate is a fickle thing.

The cloak, meant to blind the horse, slipped uselessly past its head. The beast did not rear, did not falter. Mirandola did not miss his mark.

In one fell motion he converted the downward cut on his right side into a downward thrust towards his left side. His sword ran Mancino clean through the chest.

The blow had such force that Mirandola’s own grip failed, and as he rode past, the sword remained buried in Mancino’s body.

Mancino collapsed to the ground, the handle of the sword protruding from his chest.

Mirandola wheeled his horse around, dismounted, and strode over to his fallen enemy. He could hear the air hissing through Mancino’s teeth as he clung to his last breath.

“Where is he? Where is Hannibal?”

But Mancino da Bologna was already gone. He had fought bravely, and in doing so, earned himself a warrior’s death. His fellow conspirators would not be so lucky.

Those who had survived the ambush surrendered, hoping for mercy. They received none.

Dragged back to Bologna in chains, they were paraded through the streets—a grim warning to the city. The people watched in silence as Alidosi’s men led them into the dungeons, where he had them tortured until the last secrets were wrung from them.

Then, at last, they were taken to the gallows.

One by one, they were hanged inside the city and left to swing in the wind.[4]

And Alidosi watched it all with satisfaction. His enemies were dead.

And for now, at least, Bologna belonged to him.

[1] The plot and the following action with Mancino da Bologna are described in Ghiradacci on pp. 391-393.

[2] Dialogo della Imprese, Giovio, p.16. Note that Giovio identifies this as belonging to the famous duelist Sebastiano, but I believe he is mistaking these two brothers since Sebastiano was a famous leader of infantry but necessarily a famous duelist.

[3] Swanger, the Duel, pp. 203-204.

[4] Ghiradacci, p.393.

[1] Alidosi had been the legate of Bologna for a brief time before this, but his greed had made the Bolognesi object to his presence and he had been temporarily recalled.

[2] This was done both by the previous governor and continued under Alidosi.

[3] Ghiradacci recounts how the fines were 55,000 ducats in total while the contractor rebuilding the Palazzo Marescotti was only charging 17,000 ducats.

[4] Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, Bk I, Chapter XXV

[1] The most famous of these being Lorenzo Costa who also painted the famous picture of the Bentivoglio family now in the Basilica of San Giacomo.

[2] Ghiradacci, p.378.

[3] www.condottierediventura.it, entry for “Lucio Malvezzi.” Sanuto Vol VII, col. 155

[4] There is some dispute about the order of this. According to Vizani this happened immediately whereas Ghiradacci has this happening a few days after Scappi’s revolt.

[1] Ghiradacci, pp. 374-375. This is apparently the original letter and not just Ghiradacci’s imaginings. The translation has been reworked for clarity and brevity.

[1] Ghiradacci, p.370

[2] Sanuto, Vol VII, Col. 74.

[3] See Vizzani, p. 470.

[4] See www.condottierediventura.it, entry for “Lucio Malvezzi.”

[5] Ghiradacci, p.371

[6] Ghiradacci, p.371

[7] Ghiradacci, pp. 373-374.

[8] De Bianchi, pp. 19-20.

[9] Ghiradacci, p. 375