“Padua Is Ours Again”

July 17th 1509. Padua, Italy

The golden Imperial banners atop the battlements of the city of Padua hung limp in the still dead air of a sultry Italian summer. The Imperial eagles on the flags looked flaccid and weak.

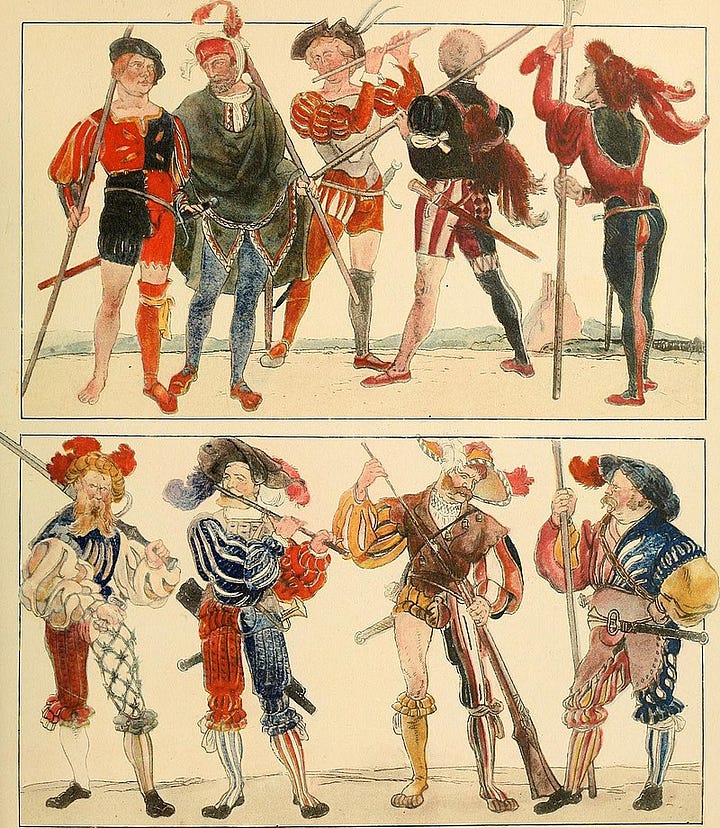

At a gate on the Northeastern side of the walls a half-dozen Landsknechts lazed about in brightly-colored hose and jackets as they sweated out the afternoon heat, miserable inside their woolens. They grumbled in their dialectical German, wishing forlornly for a breeze to give the humidity a stir. It was the kind of day that made a Bavarian or an Austrian dream of crisp breezes off the Alpine snow.

There was a cool that was coming to these men, but it was the chill of the crypt and not the fresh mountain breezes of home.

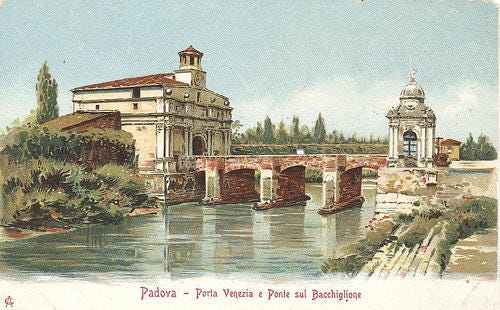

That day was going to be a big day for Padua. The city was newly-conquered by the Emperor, taken from the Republic of Venice. Technically, the city was still at war with Venice. But today marked the first day that trade was resuming between Padua and the Republic, a trade that was vital to the economy of Padua, a trade that was vital to keeping the people of Padua loyal to the Emperor.

At the sight of approaching wagons and merchants on horseback, the German soldiers stood up and made themselves look more presentable. They were supposed to make a good impression. Three large wagons trundled slowly toward the Coda Lunga gate, wagons heaped with goods from Venice and preserved fish from the Adriatic Sea. Fish and meat had been scarce in the city for months, and the fish would be a welcome addition to the local diet. The landsknechts had been told to be especially welcoming since that day, July 17th, was an important holiday for the people of Venice and the lord of Padua wished to establish good relations with the Republic.

The guards took a cursory look through the goods in the wagons and as everything appeared to be in order, they opened the gates for the merchants. The first two wagons crossed through the gate without issue, but strangely the last wagon broke down right at the threshold of the gate.

The German guards started swearing at the merchants as the gate was now blocked. Who knew what kind of Hell they were going to catch for that? The Venetian merchants were flustered. The head merchant started yelling at the driver of the cart, and the staccato of his angry Venetian just irritated the German soldiers even more.

The cart driver pointed to the axle on his cart and started yelling back at the merchant. The axle on the last had broken just as it went through the gate. It was just the worst kind of luck.

Or the best kind.

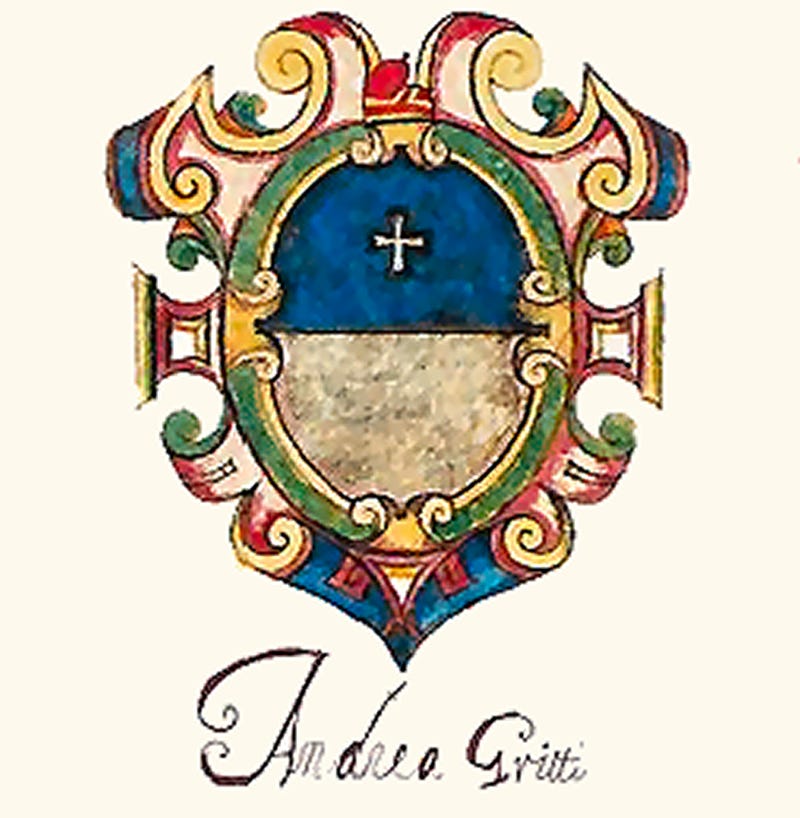

The landsknechts trying to deal with the cart did not see the riders approaching the city at a gallop. The riders bore with them the cross of St. Mark, the flag of the Republic of Venice. At the front of this group rode an old man of fifty-five years, his white hair and white beard trailing behind him. This was Andre Gritti, and this attack on Padua was his brainchild.

Behind Gritti came dozens of cavalrymen at first. But then soon there were hundreds riding hard for the Coda Lunga Gate. There were men-at-arms with their plate armor glinting in the sun, lances on thigh and riding fine horses looking for a fight. And so too there were light cavalrymen on more common horses, men trained to shoot a crossbow from the back of a bouncing horse. And with them came the strattioti, wild scouts and raiders from Greece and Albania.

The men up on the battlements were the first to notice and were soon calling for their brothers-in-arms to close the gate, but the wagon below was far too heavy to move.

Soon the landsknechts had to abandon their effort and grab their pikes. They formed up with points before them against the Venetian soldiers now crossing the bridge, but a hail of crossbow bolts sent them running for cover.

A short quick fight developed at the gate. Landsknechts with their pikes and Paduan militia with crossbows and hand guns tried to fight off the Venetian men-at-arms in full armor supported by their own crossbowmen.

The garrison of Padua had no chance. Soon people were fleeing the city of the Padua like rats from a sinking ship.

Within in an hour or two Gritti was sending word back to Venice. “Padua is ours again.”

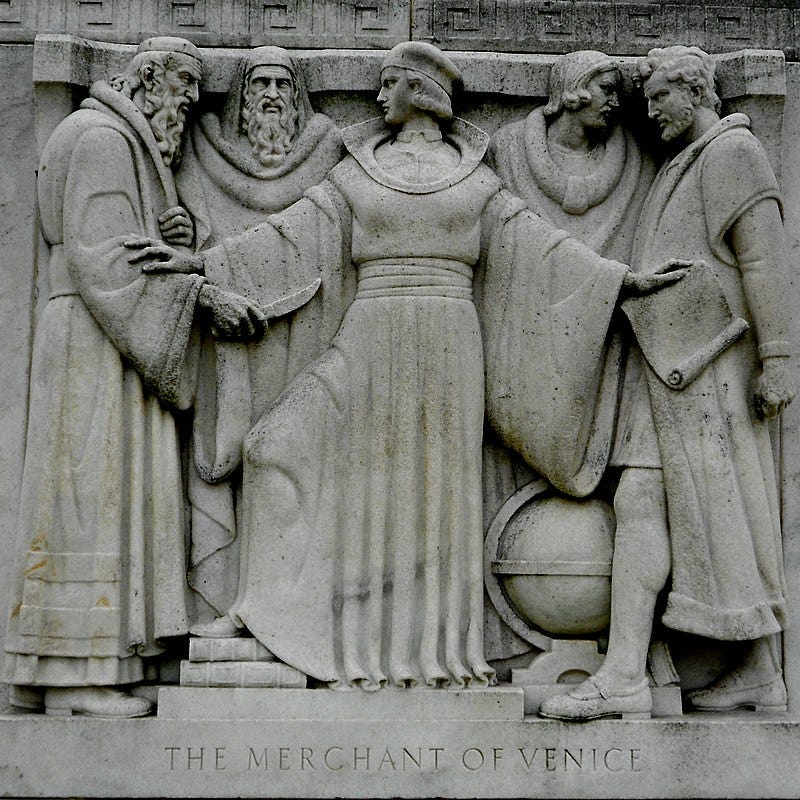

A Merchant of Venice

Born on this day in 1455, Andre Gritti first became notable as a Venetian merchant and playboy in Constantinople. He was a hard businessman making profitable deals by day and running after the beautiful ladies of the city by night. Over time Andre Gritti amassed a small fortune and made important friends. At some point he also decided to start spying for Venice, focusing on the movement of the Ottoman fleet[1]

The good times came to an end when he was caught spying for Venice. He came within a hair’s breadth of having his head chopped off, when the Sultan, a friend, chose to spare his life. Gritti was confined to prison for four years, while Venice and the Ottomans made war upon one another. When he emerged from prison in 1499, he was financially ruined and pushing fifty.

Another man might have considered his life over at that point. But Gritti was just getting started.

So where does a ruined man on the downhill side of middle age turn next? That’s right, you guessed it—he went into politics.

Over the next few years he slowly worked his way up the ranks of Venetian administrators. But he really came into his own when the Kingdom of France – and everyone else in Europe – decided to make war on the Republic.

The French invaded Venice’s mainland territories, the farmlands and cities of Northeastern Italy. And in one battle[2] the French destroyed half of Venice’s army and sent the other half running for safety. The other half of Venice’s army melted away like dew in the sunlight, deserting by the thousands as it retreated back to the lagoon.

Venice’s cities on the mainland opened their gates to the armies of France and to France’s ally, the spendthrift Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian “No Money Max” of Hapsburg. In the space of a few weeks, Venice lost almost all its holdings on the mainland, lands acquired through centuries of effort and sacrifice.

The question was whether the Venetians could hold on to what they had rather than whether they could hope for new gains. Such was the position in Valiá where, in one days engagement, they lost what it had taken them eight hundred years' exertion to conquer."

—Niccoló Machiavelli, The Prince

The greatest loss to Venice was Padua – the second most important city in the Republic and also a bulwark to the defense of the city of Venice.

The way was now open to Venice itself. It seemed just a matter of weeks or months before German and French troops were pillaging the Rialto.

But then came a gift. The new Lord of Padua, and subject of the Holy Roman Emperor, wanted to open trade between that city and Venice. While the two were at war with one another. This was a marvel to the merchants of Venice. His request was so stupid, so ignorant of the situation, so asinine that they suspected a trap. Could the new Lord of Padua be that stupid?

Um, yes he could be.

Many in Venice demurred at the chance of trying to retake Padua, but Andre Gritti thought the situation too perfect to pass up. He convinced the ruling council of Venice that they should try to retake Padua. Then he quickly assembled a small army and threw together a hair-brained plan to send in a wagon whose axle would break right when it was under the portcullis of the Coda Lunga Gate. This would allow his troops to storm the city.

It was a crazy idea and a crazy plan. But when your back is to the wall and crazy is all that you have left, what else are you going to do?

The Statesman

After this coup in Padua Andre Gritti became one of the foremost political leaders in the Republic of Venice. Though an old man with no military experience, and a civilian, he never shrunk from battle and led his armies from the front, sword in hand and was captured in battle on at least one occasion, in Brescia in 1512. We will not get into the details of these here. I especially do not want to give away any spoilers about the Siege of Padua in 1509 except that it is a fascinating topic and one that I intend to wade hip deep into here sometime in the future.

Suffice it to say that through his dogged determination and wisdom Andre Gritti was able to steer the Republic of Venice to safety at a time when almost every other state in Italy was succumbing to foreign powers.

At the age of sixty-eight Andre Gritti became the Doge of Venice, kind of like the President of the Republic. It was the highest office, the highest ambition a Venetian could aspire to. Not bad for a man who seemed to have no future just twenty years before.

As we come upon New Year’s Day and we think about our own personal goals for the upcoming year, Andre Gritti is a good reminder that success and failure are just transitory road bumps on the road of life. Only determination is a constant.

Happy New Year to you from the Art of Arms.

[1] He would send coded messages to Venice describing the galleys as rugs. So he might describe the entry of three galleys into the harbor of Constantinople as, “today I received three rugs from Syria, one in need in need of repair, but the other two in sail ready condition.”

[2] The Battle of Agnadello, where the Master of Arms Pietro Monte died.