“Church, Church!”

The Italians of the Renaissance had elevated the art of surrender to near perfection.

On November 10th, Pope Julius II entered Bologna, a city that had, just a week prior, belonged to the once-mighty Bentivoglio family. But the Bentivoglio were gone, having hastily abandoned their rule, leaving behind a city eager to display its devotion to its new master. Bologna welcomed its so-called liberator with a spectacle fit for a conquering emperor. Hugo Pepoli, a scion of one of the city's noble families, led a dazzling procession of one hundred young noblemen, each clad in resplendent "yellow and purple silk outfits with matching stockings—the Pope’s personal colors," their "velvet caps adorned with white feathers." They jostled and elbowed one another for the sacred privilege of carrying the Pope’s litter into the city.[1]

As they bore him aloft like a triumphant Caesar, the Pope’s treasurer rode ahead, flinging silver and gold coins into the throngs. Each coin gleamed with a pointed inscription: “Bologna Liberated from Tyranny by Julius.” The people of Bologna, ever enthusiastic for spectacle, met the Pope with wild cheers of “Church, church!” In a fit of near-maniacal devotion, they pressed forward, throwing themselves onto the ground, clutching at his robes, and even kissing his feet—feet that, had this been two years later, none would have dared to approach, as they would be riddled with syphilitic ulcers.[2]

The Pope did not march alone. Alongside his vast entourage trailed his troops, as well as the long-banished Bolognese exiles of the Malvezzi and Marescotti families. None among them exulted more than these men, for the Pope’s triumph was their long-awaited vengeance. The Bentivoglio had murdered their kin and driven them from their homeland. Now, at last, they had returned—and they thirsted for justice.

Soon, the city would taste the signature dish of Renaissance Italy: revenge.

Iron Fist in a Velvet Glove

The Bentivoglio were gone, but their shadow still loomed over the city. The people, long seething under their rule, unleashed their fury in a wave of mockery and destruction. Scornful verses appeared on walls and doorways, their venom sharp as steel:

“Bentivoglio at last misfortune has found you, Now not even the miserable wish you well. Once so lucky, but now Malevolence takes you, Only too soon will you be in Hell.”[3]

But for some, mere words were not enough. One enraged citizen, denied the pleasure of striking down Giovanni Bentivoglio himself, sought another target. He stormed into the Church of the Madonna di Galliera, where a stucco statue of Giovanni stood defiantly in armor, sword at his side. The inscription beneath it declared: “I defended my homeland as a youth and will not abandon it as an old man.” But the Bentivoglio had abandoned it. Enraged beyond reason, the man ignored the sanctity of the church and the presence of the Virgin Mary. He raised his billhook and attacked the statue, shattering pieces of it.[4]

The Pope, determined to erase every trace of the Bentivoglio name, commanded that their coat of arms be stripped from buildings and clothing alike.[5] Their colors were outlawed. As if symbolically disarming their ghostly presence, he ordered the people to surrender their weapons under the penalty of three lashes.[6] His marshal soon confiscated an impressive 800 weapons—lances, pikes, spiedos, billhooks, and partisans—along with suits of armor, shields, and rotellas.[7]

Yet, weapons were not the only things the Pope sought to impose upon the city. Bologna, unlike most Italian cities, lacked a fortress within its walls—a castle from which an overbearing lord might unleash his men at a moment’s notice, striking down enemies in the dead of night. Julius would change that. He ordered shops razed to make way for a new fortress, and to ensure no one dared challenge his authority, he invoked a solemn curse upon any who might harm it.

These measures did not sit well with the people. To take away the arms of the Bolognese—this was an outrage. As Machiavelli himself later warned, “when you disarm a people, you commence to offend them and show that you distrust them either through cowardice or lack of confidence, and both of these opinions generate hatred against you.”[8] That hatred simmered now beneath the surface. Adding a fortress only stoked the flames.

The Storm Gathers

Julius was no fool. He knew well that many in Bologna still supported the Bentivoglio, and that the exiled family would not vanish so easily. Italian history was riddled with tales of deposed rulers returning in force.[9] And sure enough, Guido’s uncles had fled to nearby Ferrara, lying in wait like wolves at the edge of a flock while Guido returned to his castle of Spilamberto on the border with Bologna. The Pope demanded that the duke expel the Bentivoglio from Ferrara, but he simply turned a blind eye and said they were not there.[10]

To secure his rule, Julius appointed Lucius Malvezzi, a seasoned condottiere, as Captain General of Bologna’s forces. A hardened veteran who had fought up and down the Italian peninsula for twenty-five years, Malvezzi would soon find his fate entwined with Guido Rangoni, first as a foe, and later as an uneasy ally.[11]

But not all of Julius’ actions were oppressive. To placate the people, he cut taxes and fixed the prices of food and wine. He also adorned the city’s churches, most notably commissioning a grand bronze statue for the entrance of the city’s cathedral—a towering, awe-inspiring figure of himself.

With one hand raised in benediction, Julius II blessed the city. In the other, he held a sword.

Michelangelo himself, upon finishing the statue, observed that it was “more a threat to the people of Bologna if they were foolish.” Foolish enough, that is, to think of bringing back the Bentivoglio.[12]

Julius spent four months in Bologna, but his stay was cut short by threats from the King of France, who delighted in tormenting the Pope by reminding him that, with nothing “more than a single letter,” he could restore the Bentivoglio to power. On February 22, 1507, Julius departed for Rome.

Hardly had his carriage passed through the eastern gate when his legate ordered the execution of several citizens accused of corresponding with the Bentivoglio. The city, now a vassal of Rome, chafed under the yoke of foreign rule. The Senate, once the pride of Bologna, had been reduced to a ceremonial puppet of the Pope’s representative.

The Bentivoglio supporters sensed their moment. They whispered in dark corners, calling for the return of their exiled lords. In response, Julius placed a bounty on Hannibal and Hermes Bentivoglio: four thousand ducats for their capture alive, two thousand for their heads.

Even nature seemed to mourn the Bentivoglio’s absence. A chronicler wrote:

“Since Lord Giovanni Bentivoglio left Bologna, which was on the 2nd of November 1506, until this day, there has been neither snow nor enough rain to properly soften the land … now [1507] there is a shortage of both bread and wine, among other things.”[13]

As if this were not bad enough, there was soon an outbreak of plague in Bologna.[14]

God Can Wait for Me

The time for waiting was over.

Grandma Bentivoglio—indomitable, relentless, and possessed of a will as unyielding as iron—had made up her mind. Bologna must be reclaimed. Her husband, Grandpa Bentivoglio, ever cautious, urged patience. He counseled waiting—waiting for Pope Julius II to die, waiting for unrest to fester into rebellion, waiting for fate to do what he feared to do himself, waiting for God to present the right situation.

But Grandma Bentivoglio had no patience for cowards.

Once again, she chose action.

With a fierce resolve, she liquidated her treasures, raising fourteen thousand ducats—a war chest, small compared to the vast fortunes spent by the Pope, but enough to fund a rebellion.

She summoned her grandson, Guido Rangoni, along with his cousin Alexander Pio, and her own sons. The time for words was past. She placed the money in their hands and issued her command: return to Bologna and reclaim our home. Let the men of this family do what their grandfather lacked the stones to do—conquer.

The response was swift.

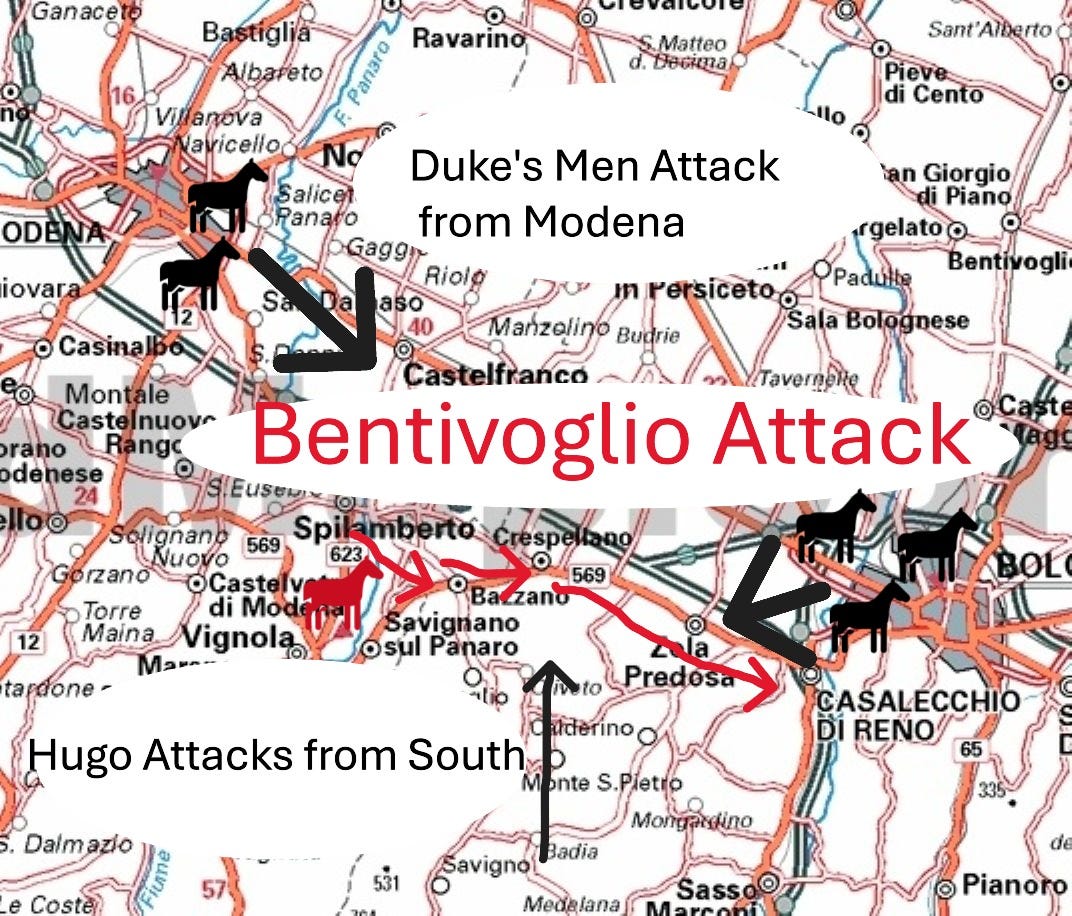

From Mantua to Modena, the Bentivoglio banner was unfurled. Guido Rangoni raised troops in his ancestral lands of Spilamberto.[15] His childhood companion, Alexander Pio, did the same in Sassuolo. Their uncles scoured the countryside for soldiers. Within weeks, an army had formed—six thousand men, six hundred of them armored cavalry, a handful of cannons, and the fire of vengeance burning in their chests. By the last weeks of April, this force gathered at Guido’s castle of Spilamberto, standing on the very border of Bolognese lands.

The invasion was at hand.

Let the Panaro Be Our Rubicon

Before the sun had even crested the horizon on May 1st, the first troops moved out.

Under the cover of pre-dawn darkness, Uncle Hermes led his mounted crossbowmen across the Panaro river into Bolognese territory.[16] Guido Rangoni followed with his men-at-arms, many of them veterans who had once served under his father.

The attack was no secret. A force of this size could not be raised without whispers reaching Bologna. The Pope’s man in the city, Lucius Malvezzi, had been forewarned. He acted swiftly, “rounding up 300 suspected Bentivoglio sympathizers and exiling them to Faenza, some forty miles away.”[17]

But exile was not his only weapon.

Malvezzi bolstered the city’s defenses, ordering all but three of Bologna’s gates to be sealed and barricaded. No last-minute conspirators would be opening the city to the Bentivoglio. Inside, he summoned the militia, outfitting them with arms and marking them with a red cross on white—the insignia of those who stood for the Church against the Bentivoglio.

And then came the mercenaries.

Two infamous condottieri rode to Bologna’s defense: Ramazzotto, known as “The Priest”—a man whose troops were as skilled in plundering as they were in battle—and “Mad Dog” Sassatello, a man who had earned his bloodcurdling name after ripping an enemy’s heart from his chest and biting into it while it was still warm.[18]

With war looming, Hugo Pepoli prepared the decisive blow. He went into the mountains, gathering his veterans from the Siege of Pisa as well as other hardened mountain men. The Bolognese mountains were a wild country where often law was the law of vendetta and violence came natural to these men.

March of the Bentivoglio

At dawn, the Bentivoglio army surged forward.

Unlike most armies of the time, which took what they pleased from terrified peasants, the Bentivoglio paid handsomely for food and drink along the way. This was not mere charity—it was strategy. They sought to win the hearts and minds of the countryside, to sway the people of Bologna itself. Their march was not just an invasion. It was a campaign for loyalty.

Guido and his men-at-arms rode at the vanguard, taking the lead down the Wine Road, a well-trodden path that wound through the countryside toward Bologna.[19] They were accompanied by the finest commanders of their army, including the feared Mancino da Bologna and his brother Sebastian.

At first, everything went according to plan. The first two castles surrendered without a fight.[20] The countryside rose in support. Messengers from inside Bologna rode out to meet them, bringing news of the city.

And that news chilled Guido Rangoni to the bone.

Lucius Malvezzi had been ready for them. Long before the first Bentivoglio soldier had set foot in Bolognese territory, the city gates had been barricaded. No sympathetic hand would swing them open. Bologna would not rise in rebellion.

And worse still—troops were mustering behind them in Modena.

The Bentivoglio army now stood between the walls of Bologna and the threat of encirclement.

The Trap Closes

Time was running out.

To secure their position, the Bentivoglio demanded the surrender of Piumazzo, a decrepit fortress whose garrison consisted of “seven soldiers and four crossbowmen.”[21] Yet, against all odds, Piumazzo refused to yield.

With the Modenese force looming behind them and Bologna’s walls sealed ahead, Guido and the Bentivoglio had no choice. They pressed forward.

In response, Lucius Malvezzi tightened his grip, pulling his troops closer to Bologna, daring the Bentivoglio to advance.

Seizing the moment, Uncle Hannibal made his move. He hurled his cavalry forward, banners unfurling in the wind, the sigil of Uncle Hermes—a pear on a white field—leading the charge. Close behind rode the armored cavalry, bearing Guido Rangoni’s silver shell.

They galloped toward the walls of Bologna, gambling everything on one desperate hope—that the people of the city would see them, remember their loyalty to the Bentivoglio, and rise in revolt.

But the people of Bologna did not rise. Instead, they armed themselves against the Bentivoglio.

And then, like the snap of a wolf’s jaws, the trap was sprung.

Hugo Pepoli’s mountain warriors descended from the hills, cutting off the Bentivoglio from their supply lines. At the same time, the militia of Bologna, led by Alexander Pepoli, charged out of the city gates, reinforced by The Priest and Mad Dog Sassatello.

Guido and his family had been outplayed.

A massacre loomed.

Retreat or Die

The warning of danger approach reached Guido and Uncle Hannibal—Hugo’s men were closing in from the rear.

There was only one choice.

Retreat.

Hannibal ordered the entire Bentivoglio force to withdraw back across the river.[22] They had been defeated, but at least they would live to fight another day.

For Guido Rangoni, there was no satisfaction in survival. Once again, Hugo Pepoli had bested him.

Recognizing the futility of further resistance, Hannibal struck a deal with his brother in law, the Cardinal of Ferrara. The Bentivoglio were permitted safe passage.[23] Their army scattered. The last report placed them near the fortress of Mirandola, heading for Mantua.[24]

The dream of reclaiming Bologna was over.

Failure is a Four Letter Word

It was a catastrophe.

Before the failed attack, the Bentivoglio had at least been tolerated in Ferrara. Now, the Duke expelled them.[25]

With a price on their heads—four thousand ducats alive, two thousand dead—Hannibal and Hermes Bentivoglio were forced into exile, constantly on the move.

And Grandpa Bentivoglio, who had stayed out of the affair entirely and been living in quiet comfort in Milan, now found himself thrown into the dungeons by the King.

As for Guido Rangoni? His ancestral castle at Spilamberto was stripped from him. He was left under watch in Ferrara, his every movement scrutinized.

And Hugo Pepoli? He returned to Bologna a hero.

For now. Because in Bologna, victory and disaster were two sides of the same coin.

And soon, Hugo Pepoli would find himself in the doghouse with His Holiness. For there was a celebration going in Bologna and as the wine flowed, trouble also flowed into the city, trouble that would change everything for Hugo Pepoli.

Find out how on the next Episode of Death Before Dishonor: Some Heads Are Gonna Roll.

[1] Ghiradacci, p.355. Note that Ghiradacci does not specify which noble youths and it’s quite possible that Hugo was not among them. But certainly, someone from the Pepoli family would have been among these, and it may have been one of his brothers that carried the Pope instead.

[2] Vicars of Christ, The Dark Side of the Papacy, Peter de Rosa, Crown Publishers New York, 1988. P.105. Pope Julius was the first Pope to get syphilis and to have a private space for his treatment he even had a special bathroom added into the Vatican. See Raimond-Waarts, L. L., & Santing, C. (2010) “Sex: A Cardinal’s Sin. Punished by Syphilis in Renaissance Rome. Leiden University, p.179.

[3] Ghiradacci, p.354. Note here is actual poem, “Bentivole, heus tandem mala sors, sed una, sequuta est / Non bene iam misero sed male quisque cupit/ Bentivola ecce prius fortuna, Malivola nunc est/Multivolumque cito, Mortivolum faciet.” Translation reflects the feeling more than the literal interpretation.

[4] Ghiradacci, p.366.

[5] Ghiradacci, p.359.

[6] Ghiradacci, p.360.

[7] Ghiradacci, p.367 “cioè 800 pezzi d'arme in hasta, fra lanze, lanzoni, spiedi, ronche et parteggiane, 12 armature d'huomini d'arme, corazze assai da pedoni fornite signorilmente, et molti targoni, targhe et rotelle.

[8] Machiavelli, the Prince “Whether Fortresses, etc…”

[9] Shaw, Julius II, p. 145.

[10] While the presence of the Bentivoglio men in Ferrara is attested, that of Guido Rangoni is merely an educated guess. He may also have just retired to his castle in Spilamberto.

[11] See www.condottierediventura.it entry for “Lucio Malvezzi.”

[12] Condivi, Vita, p.63. Note that this story may be more apocryphal than literal. Note some authors like Bianchi think the statue was built on the initiative of the Bolognese but this seems specious.

[13] Cronaca Modenese, de Bianchi Vol I, p. 46.

[14] Ghiradacci, p.368. It’s not clear exactly what plague, but outbreaks of bubonic plague had become endemic to the crowded cities of Northern Italy.

[15] De Bianchi, Vol I, p.16. Note in this section, de Bianchi describes a number of different assembly points, but the main path of castles taken in the campaign strongly indicates the final debouchment occurred from Spilamberto.

[16] This is suppositional based on the typical methods used in warfare then and now to use light mobile troops for reconnaissance in advance of the army.

[17] Sanuto, col. 68

[18] www.condottierediventura.it, see entries for “Melchiorre Ramazzotto” and “Giovanni Sassatello.”

[19] This was the Via del Brentatori, that connected the town of Monteveglio with downtown Bologna. See: www. https://www.bolognametropolitana.it/Home_Page//001/In_cammino_da_Bologna_a_Bazzano_rinasce_la_Via_dei_Brentatori. Retrieved 8/23/24. Note the placement of Guido in this army is suppositional.

[20] These would be the Rocca dei Bentivoglio and the castle at Monteveglio, the start of the wine road.

[21] The worn-down castle of Piumaggio, whose “drawbridge could not even be lowered or raised.” S. MANTOVANI, Fortificazioni estensi nella pianura tra Modena e Bologna, in Rocche e castelli lungo il confine tra Bologna e Modena, cit., p. 182. See Castello di Piumazzo: Storia Ed Eveluzione Construttiva Tra Notizie Storiche Ed Evidenze Struturrali, Francesa

[22] Note that Ghiradacci says that Hannibal removed them to Modena, but he almost certainly meant the province of Modena and not the city.

[23] Bianchi pp.18-19. Note there was also a raid of little importance that he had made towards Casalecchio to cut the city’s water supply.

[24] Libro delle historie ferraresi. Sardi, Gasparo, 1646.

[25] The Bentivoglio of Bologna: A Study in Despotism. Cecilia Ady 1938