After the bloody battle at Ravenna in April of 1512, the mighty legions of France stood triumphant over all of the Northern Italy. Their forces, led by the mighty Gendarmes of France, had washed like a bloody tide from the Mediterranean to the Adriatic sea, driving all of their enemies from the field. The Venetians, the Spanish, the armies of the Pope, all of these had been smashed and sent running.

Hugo Pepoli and Guido Rangoni were near Venice. The Venetian forces were trying to recuperate from their defeats by the French juggernaut. Venice had promoted the bold and ambitious Guido Rangoni, granting him an additional 25 lances, bringing his total to 100 men-at-arms. But even this boost fell short—Guido simply could not find enough capable men to bring his company to full strength. As lieutenant to the Captain General of the Venetian army, Hugo Pepoli was helping his boss to rebuild the Venetian army.

But their efforts were failing. After three grueling years of relentless warfare, the Republic of Venice had little to show for its sacrifices beyond survival. Its mainland dominion remained pitifully small, confined to the areas around Padua and Treviso. In the past they had been able to find new forces after each defeat, but now service in the Venetian army eemed to many like a one-way trip to the poor house or the grave.

The small Venetian army could only look at the mighty French forces and tremble.

The Pen and the Sword

They were not alone. In Rome, Pope Julius II and his Cardinals trembled at the thought of the French marching on the Vatican and throwing him out. Pope Julius worked desperately with his pen and his coffers to bring a long-cherished plan into motion: to get the powerful Swiss cantons—miniature independent republics—into the field against France. Over the years he had succeeded in getting a few into arms to fight the French, where their fearsome infantry posed a major threat to French conquests in Italy.

But in June of 1512, the Pope hit paydirt. He succeeded in getting the entire confederation of Swiss cantons to fight against the French.

Then, two months after the battle, the Alps trembled as 24,000 Swiss pikemen poured down from the mountains, lured by Julius' promises of pay and the prospect of loot. The French were dangerously overextended with their armies at the Adriatic, since the Swiss could were in a position to cut the French supply lines. Realizing their peril, the French hastily withdrew, pulling their forces back to defend their strongholds near Milan.

In doing so they abandoned the Bentivoglio to the Pope.

So six months after holding off the Spanish army outside Bologna, Guido Rangoni’s Bentivoglio relatives were forced to abandon the city—lest the Sensing the shifting winds, the Bentivoglio family fled Bologna before the Pope could put their head on a spike. They sought sanctuary with relatives in Ferrara, where the Duke of Ferrara, playing a high-stakes game of chicken, now placed himself under the protection of the Emperor—keeping Julius at bay, for the moment.[2]

Trouble in Paradise

For Hugo Pepoli and the Venetian army, their the Swiss allies, would prove to be a fountain of trouble. Julius II had drawn the Swiss from their Alpine valleys with the lure of payment, yet he had little coin to give. The Swiss, undeterred, decided to take their due—by pillaging Italian lands with ruthless efficiency.

By July 1512, tensions boiled over. A bitter dispute over loot between the Swiss and the men of Hugo Pepoli and John Paul Baglioni’s men erupted into violence, leaving fifteen Swiss pikemen dead.[3] Outraged, the Swiss thirsted for vengeance. Soon after, they captured two Venetian paymasters and held them hostage, demanding the 14,000 ducats that Venice owed them.[4]

The situation teetered on the brink of disaster. Rather than negotiate, the fiery John Paul Baglioni rallied his artillery and ordered Hugo Pepoli to muster the men-at-arms—prepared to slaughter the Swiss if necessary.

Thankfully for the Venetian alliance, diplomacy won the day. Venetian officials stepped in, offering reparations for the lost plunder, and the Swiss, appeased, released their captives. A deadly battle between supposed allies was narrowly averted.

Back to Brescia

In our last episode we looked at the French conquest and sack of Brescia. With the French clinging to only a handful of strongholds, Venice saw an opportunity and sent Hugo Pepoli and Guido Rangoni to reclaim the city.

Guido had moved up in the world from commander of light cavalry to captain of men-at-arms, to command of a colonello, a division with all the elements of a Venetian army,—men-at-arms, light cavalry, infantry, artillery, and engineers. It was his moment to shine.

He would fail spectacularly.

Guido learned the harsh lesson that many a young warrior gets as he climbs up the ranks. It is far easier to disrupt an enemy’s supply lines than to maintain your own. Despite having artillery, he was at the mercy of Venetian administrators for gunpowder, which they either could not or would not provide.[5] Worse still, Guido found it impossible to get his guns into range. Standard practice required sappers to dig approach trenches, but no peasants were willing to take on the task, and his infantry outright refused the duty—even when tempted with extra pay.[6]

His struggles were not unique. The entire Venetian force suffered from supply shortages. The Venetians, rather than breach the walls in a full-scale assault, turned to negotiation. Their eagerness was almost comical—so many envoys approached the French under white flags that the exasperated commander of the garrison threatened to shoot the next one.[7]

The siege spiraled into a farce. Finally, the French agreed to surrender Brescia—but only to the Spanish. The Spanish accepted, allowing the French garrison to depart unscathed. When the Spanish banner was raised over the city walls, the Venetians erupted in fury. Brescia was supposed to be theirs! [8]

For Guido Rangoni, if he thought he had faced difficulties with Venice’s civilian leadership before, he was about to enter an entirely new level of Hell.

Paper Pushers

The Venetian system of pairing mercenary captains with civilian overseers was a recipe for friction that would derail Guido’s meteoric rise.

As the autumn chill set in around the city of Brescia, Guido, defying orders, housed his cavalry in villages rather than subject them to the muddy misery of camp life. This angered many Venetian officials.

Tensions exploded when some of his infantry resorted to looting after the Venetian government failed to pay them. A Venetian superintendent intervened, attempting to reassert control.[9]

Then came the breaking point.

A heated meeting was arranged between the Venetian collateral general—the supreme paper pusher—and Guido Rangoni, as well as other key figures. The discussion quickly turned to confrontation. When the Venetian official berated Guido for ignoring orders, tempers flared—insults were exchanged, swords were drawn, and in an instant, steel clashed in the chamber. Guido and the Venetian collateral general lunged at one another with drawn swords. They would not hurt one another, but an abbot in the room who was trying to bring peace between these two men, suffered a head wound in the scuffle.[10]

The violence did not end there. The very next day, Guido challenged this Venetian administrator to a duel, a move that scandalized Venetian authorities as “very shameful.”

John Paul Baglioni managed to convince Guido to withdraw his challenge, seemingly bringing the matter to a close.[11] But the damage had been done. Guido had humiliated a Venetian official, setting off a chain of political revenge in Venice.

Guido the Embezzler

The storm brewing against Guido reached its peak after the debacle in Brescia. The Venetian government received a damning accusation against one of its administrators—a political ally of Guido Rangoni. The charge? That he and Guido had embezzled funds meant for the siege of Brescia. Here then was an explanation why Guido Rangoni could never get enough gunpowder.[12]

Here Rangoni’s enemies were plowing fertile ground: given Guido’s financial troubles, the accusation seemed all too believable. Ever since he had been captured and forced to pay his own ransom the year before, Guido had struggled to rebuild his fortune. Unlike many condottieri, he had no vast personal wealth. Venice had even granted him financial aid in the summer of 1512.[13] If he had skimmed siege funds to buy gunpowder, it would hardly have been surprising.

Guido, however, refused to go down without a fight. He demanded a hearing and defended himself well enough for the matter to be dropped.

But his enemies were relentless. Calls for his dismissal continued.

Under normal circumstances, Guido would have been thrown to the wolves. But Venice was in turmoil.

End of an Era

By the end of 1512, the once-mighty French gendarmes had been driven beyond the Alps. The victorious Holy League of Pope, Germany, Venice and Spain had won. But as with any pack of hunters, when the prey lay dead at their feet, unity began to crumble.

Bologna had fallen into Pope Julius' grasp like a ripe pearl. But he was not satisfied there. His true prize was Ferrara. Yet, the Emperor had declared Ferrara under his protection and sent reinforcements to defend it.[14] If Julius wanted Ferrara he had to pay the Emperor’s price: virtually all of Venice’s mainland territories. The Pope pushed for Venice to give the Emperor what he wanted, but Venice naturally refused.

In late November, Guido Rangoni received a letter from Rome, warning Venice of a new league being formed by the Pope and the Emperor—a pact that would strip Venice of its lands. [15] The Pope vowed to use both spiritual might and military force to bring Venice to heel.[16]

Venice refused to bow. It turned to France. In retaliation, Pope Julius II excommunicated the entire Republic.[17]

But the Pope had exhausted himself in his crusade against the French. He watched in horror as Venice, the very state he sought to subjugate, aligned itself with France.[18] The realization shattered him. On February 20, 1513, Pope Julius II took his final breath.[19]

In Rome, the death of Pope Julius II sent shockwaves through the city, unleashing a storm of grief and terror. Fear gripped the streets, not just for the loss of the pontiff, but for what came next—the dreaded interregnum, the lawless void between Popes. This was the season of vendetta, of old feuds reigniting, a time when settling scores became a blood sport and murder was practically legal. The city had seen it before. During the interregnum of 1484, Rome averaged seventeen murders per day—in a city of only 50,000 souls.[20]

Amid the chaos, Hugo Pepoli and Hermes Bentivoglio seized the moment. The time had come to reclaim Bologna for the Bentivoglio family. They wasted no time, rallying a force of infantry along the border with Ferrara.[21] But their enemy was waiting. The Papal governor of Bologna had been tipped off, and he scraped together every condottiere he could muster. When Hugo and Hermes arrived, they found not an open door, but closed gates and loaded cannons.[22]

Weeks passed, and then, to no one’s surprise, Giovanni de Medici ascended to the papal throne as Pope Leo X. For Guido Rangoni, this was a stroke of fortune. His brother had long been in the service of Giovanni. Soon there would be a Rangoni cardinal in Rome. Sensing opportunity, Guido abandoned his Venetian troops and went AWOL, racing to Rome to plead his case before the Pope. He had one goal: convince Leo to let the Bentivoglio rule Bologna once more. But the dream was dead. The people of Bologna no longer wanted the Bentivoglio.

Though disappointed Guido remained in Rome. He basked in the splendor of the papal court, draped in rich brocade, flanked by footmen as he attended Leo’s coronation. Meanwhile, in Venice, the Senate debated his fate. Guido had abandoned his post. He had left without permission.

Many wanted to be rid of Guido Rangoni.

A New War

Despite their frustration, Venice had no choice. Guido’s company of men-at-arms refused to serve under anyone else. With war clouds darkening the horizon, Venice was forced to rehire not just Guido, but also Baglioni and Pepoli.[23]

Baglioni, now placing immense trust in Hugo Pepoli, sent him to Venice to negotiate payment directly with the government. Hugo tried to convince the Venetian government to pay out in advance so that offensive operations would not grind to a halt once the Venetian payment fell into arrears. The Venetians refused.[24]

As Guido made his way back from Rome, history was already shifting beneath his feet. The ink had barely dried on a bold new pact between France and Venice. The agreement was simple: Venice would help the French reclaim Milan, and in return, the French would help Venice recover the cities it had lost after the disastrous defeat at Agnadello four years prior.

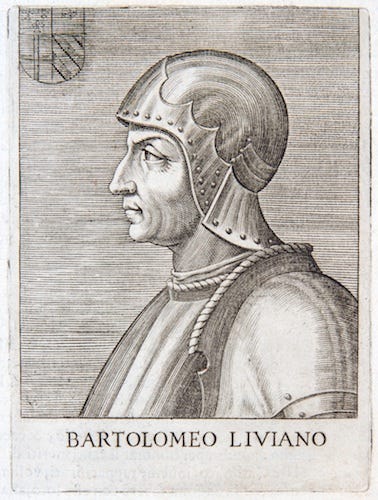

But one element of the deal was more crucial than all the rest. The French had agreed to return Venice’s greatest weapon—Captain General Bartolomeo d’Alviano. He was the only man alive who could whip the Venetian army into shape, turning it into a force powerful enough to stand against the mightiest armies of Europe.

The tide was shifting once more, and the battlefield was calling….

Can Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli help Venice defeat the armies of Spain, Germany and the Pope, or will Venice face another humiliating defeat? Find out in our next episode…

[1] Shaw, p.295

[2] Shaw, p.295

[3] Sanuto, Vol. XIV, col. 461

[4] www.condottieredieventura.it, entry for “Giampaolo Baglioni.” See also Da Porto, p. 322.

[5] See www.condottierediventura.com, entry for “Guido Rangoni.”

[6] Sanuto, Vol. XIV, col. 624.

[7] See www.condottierediventura.it entry for, “Giampaolo Baglioni.”

[8] Mallett & Shaw, p.138.

[9] Sanuto, Vol. XV, col. 261.

[10] Sanuto, Vol. XV, cols. 261-263.

[11] See www.condottierediventura.it entry for “Guido Rangoni.”

[12] Sanuto, Vol. XV, col. 429

[13] Sanuto, Vol. XIV, col. 533.

[14] Shaw

[15] Sanuto, Vol. XV, col. 375. Shaw, pp.310-311.

[16] Sanuto, Vol XV, cols. 406-408.

[17] Sanuto, Vol. XV, col. 510.

[18] Sanuto, Vol. XV, col. 492.

[19] Shaw, pp. 312-313.

[20] The Life of Cesare Borgia, Sabatini, in Chapter III, “Alexander VI.”

[21] See www.condottierediventura.it entry for “Ugo Pepoli” and “Hermes Bentivoglio.”

[22] Vizzani, pp.512-513.

[23] Ibid, col. 129