When it comes to the warlords of Renaissance Italy one name towers above all others: Cesare Borgia. He was the son of a pope and the perfect symbol of his age. He could be cultured and charming when he wished to be and ferocious when it helped him to get ahead. Above all he was a man without scruples or conscience —a pitiless winter storm set to blow across Italy. If you imagine him as Michael Corleone with a sword and syphilis, you will not be far off the mark.

It was this combination of traits that moved Niccolo Machiavelli to crush on him like a lovesick teenager. It did not matter to Machiavelli that Cesare was wicked. It did not matter that Cesare had killed his brother-in-law to free up his sister for marriage [1] Nor was it relevant that he almost certainly had his own brother murdered.[2] Or had murdered many many others. These were just issues of morality and morality paled in comparison to the importance of forcefulness – so long as a man bent and twisted the world about him according to his own designs, then what did it matter if he left a trail of dead bodies in his wake? At least that was how Machiavalli and many others thought in the Renaissance.

Cesare Borgia was bound to shape the world about him, to be a man “whom all did fear.”[3] And one place where would strike great fear was in Bologna. Young Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli would have their very first taste of military life facing his legions.

At first it did not seem like Cesare would be a problem for Bologna and the Bentivoglio. In the fall of 1499 Cesare came to Bologna as he was passing peacefully through their territory with a French army to attack the neighboring city of Imola. Grandpa Bentivoglio invited him to the Bentivoglio palazzo and there young Guido Rangoni had a chance to break bread with this famous warrior.[4] The occasion was marked by pleasantries and the exchange of gifts. The honeymoon would prove short-lived.

After conquering Imola and the city of Forli, Cesare Borgia soon led his troops back through the territory of Bologna in the direction of Milan. As they passed through, “the troops wreaked havoc in the surrounding territory, looting and killing many people.”[5]

In the early weeks of 1500, Cesare and the Pope had changed their position on Bologna. They were now scheming to drive the Bentivoglio from Bologna and so completely subjugate Bologna to the rule of the Pope. They tried to enlist the French to help them in this endeavor, but the Bentivoglio came up with 40,000 ducats to put the city under the protection of King Louis. This meant that Cesare had to shelve plans to attack Bologna, at least temporarily.

In 1500 the Pope gave his blessing to Cesare to create a new state for himself in the lands to the east of Bologna known as Romagna. Neither Pope nor Ceare could have picked a better year. 1500 was a jubilee year and hundreds of thousands of pilgrims flocked to Rome, bringing money from all over Europe, money that eventually made its ways into the coffers of the Pope.[6] With this money Cesare Borgia hired an army of some ten thousand men with most of the leading Italian condottieri of the day, including many sell swords we will meet along our journey to the duel of Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli.

In September of 1500 Borgia led this force north to conquer the territories of Pesaro, Rimini and Faenza – lands controlled by relatives of Guido Rangoni.

During this time Hugo Pepoli and Guido Rangoni were still completing their training in the skill of arms. Now that Guido was fifteen years old and fully grown, it was clear to his father and to his trainers that Guido was destined to be a small man. In the practice of the sword and other arms this was no great matter. He would simply learn how to fight from the low defensive positions or guards as they were known. Guido learned, “first to parry and then to attack thereafter,” especially with a thrust.[7]

The issue was a bit thornier when fighting with the heavy lance on horseback.

No matter how much Guido trained, he was not going to be as strong as the bigger knights he would have to battle. This meant he could count on going into battle with a shorter lance – since the longer the lance, the more it weighed and the harder it was to control the point. It also meant that an opponent was likely to hit him before he was to hit his opponent and thus lose his aim.

Luckily, Guido Rangoni was not the first knight to face this problem. As a smaller knight Guido had to learn to ride towards his opponent with the point of his lance down and towards his left side. Then once near the opponent, he trained to turn his weapon against the shaft of the opponent’s lance and nail him. The famous Italian Master of Arms Fiore Dei Liberi described this technique in his work, “the Flower of Arms.”

“I carry my lance in this Guard of the Boar’s tusk because I am well-armored, but my lance is shorter than my enemy’s. Here is my plan: I will beat his lance off to the side or upwards, so it no longer points at me. I will make this beat no further than one arm [a measure of distance] from the tip. My lance will then run into his body while his weapon will pass away far from me.”[8]

Here was a thing easier said than done. It was a stupendous achievement of timing to cross an opponent’s lance at just the right moment while trying to judge the closing speed of two charging horses from the imperfect vantage point of a rider. Though Guido Rangoni would serve as a man-at-arms, he would never been known as a great lancer or someone to fear on the jousting field.

Hugo Pepoli did not have the similar difficulty. Since he was tall and well-built, he could follow the advice on using the lance described in the previous episode by Pietro Monte. “Direct [your] spear at our opponent, and not at where [you] believe he is going to be.”[9] For Hugo Pepoli the big challenge was going to be figuring out how to get a command. The Pepoli were wealthy but not one of the well-known condottieri families of Italy. Here the advantage went to Guido.

In October of 1500 Guido’s father died.[10] This was at a time when Cesare Borgia’s forces were only seventy-five miles from Bologna and making war on Guido’s relatives.[11] Grandpa Bentivoglio now put fifteen year old Guido Rangoni in charge of his father’s company of one hundred men at arms so that the boy could learn how to command – though he found an experienced relative to help counsel Guido.[12]

While this was a great opportunity for advancement, it was also a huge responsibility after the blow of losing his father. The strain on him was apparent – Guido’s mother wrote that the young man was too ill to travel to Venice and do homage for the family’s hereditary castle in Venetian territory.[13]

The threat to Bologna and young Guido became even more magnified in November of 1500. Now Cesare Borgia led his army to the small city of Faenza, a city that lived happily under the rule of Astorre Manfredi. As you may remember from the prologue, young Astorre was Grandpa Bentivoglio’s oldest grandson and so Astorre was one of Guido’s first cousins.

On October 24th the Pope sent Grandpa Bentivoglio a missive instructing him not to interfere with Cesare Borgia’s attack on Faenza, but Grandpa said to Hell with that. Always the family man, Grandpa Bentivoglio sent a thousand soldiers—especially crossbowmen—to bolster the defenses of Faenza.[14] For plausible deniability he instructed this force to go to a Bolognese castle near Faenza, desert, and then join the garrison of the beleaguered city as though acting independently.

This charade fooled no one.

Guido Rangoni wished to fight against Cesare Borgia on behalf of his cousin, but Grandpa Bentivoglio was keeping his family in Bologna.[15] The situation of the Bolognese forces was precarious. The two leading generals of the city had been Guido’s father and Guido’s uncle Gilbert Pio. Both had died within the space of a month. To command the knights of their two companies, Grandpa Bentivoglio had given the command to his two grandsons, Guido and Alexander Pio. The two had been playmates as boys and now as young men they were commanders in the Bolognese army.[16] The time for games was over.

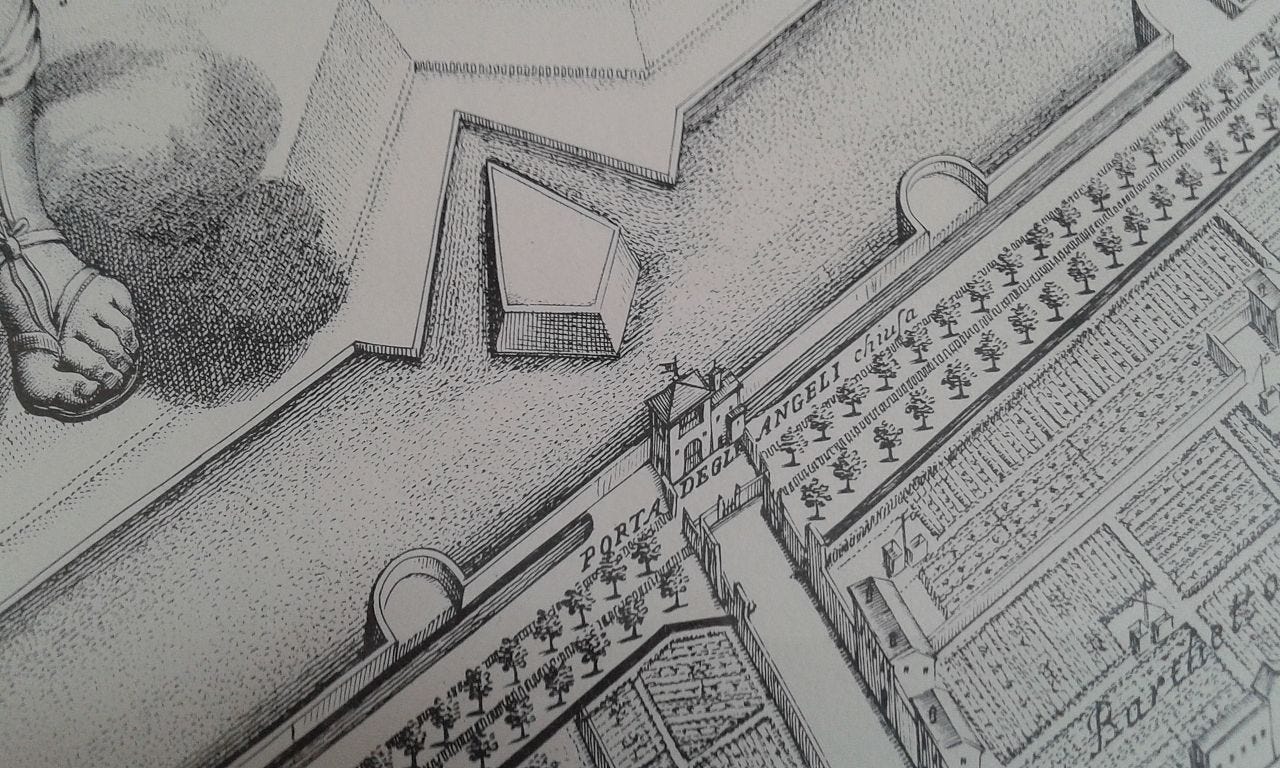

Treason was Grandpa Bentivoglio’s main concern—he knew there were those in the city who would turn Judas and open a gate to forces of Cesare Borgia for a purse full of silver if only they could. To protect the city, he ordered the gates to be controlled by members of his own family and to bolster its garrison, the Senate offered pardons to those rebels who would return and help protect Bologna.[17]

Back in Faenza things had taken a turn for the unexpected. Despite the odds and despite general expectations of a quick victory for the Borgia, the city of Faenza and its beloved 16-year-old lord held off Cesare’s army. Even when Cesare’s cannons smashed a breach in the defenses, the citizens of Faenza and the Bolognese mercenaries amongst them were able to defeat Cesare’s forces. Much credit had to go to the people of the city, who never wavered in their declaration to lay down their lives before surrendering their lord.[18] They were so devoted that even the women took their turn guarding the ramparts when their menfolk became weary.[19]

When snow started to fall in late November, the failure was official. Despite the odds Faenza was saved – for now. Cesare Borgia’s men abandoned their siege positions and went into winter quarters.

Cesare Borgia and his father put the blame for this failure squarely on the Bentivoglio family for providing reinforcements to the city. For his part Cesare made some not-so-very-subtle hints to Bologna that the Borgia bull would soon be flying from the battlements of Bologna, but the people of Bologna were not worried since they thought they could count upon France’s protection.

The failure had been an expensive one for the Pope.[20] The Pope pressured the King of France to act against Bologna and force them to recall their mercenaries. The King took the side of the Pope and ordered Grandpa Bentivoglio to withdraw the Bolognese mercenaries from Faenza. Grandpa was forced to acquiesce — he recalled the thousand soldiers in Faenza and left his grandson to his fate.

This was a bitter blow to the Bentivoglio, to young Guido Rangoni, and especially to the people of Faenza. That Christmas was a mournful one.

Cesare Borgia spent the winter season in celebration. When not being wined and dined he went about in disguise, wrestling with peasants and mule drivers, pelting people with snowballs and winning foot races.[21] While Borgia played the lazy grasshopper, the people of Faenza played the busy ant. To better protect their city, they enhanced their fortifications and erected bastions outside the walls of the city. When springtime came and the season of war began the city was as well-prepared as it could be to face Cesare Borgia’s onslaught.

Borgia’s commander of artillery was an experienced condottieri known as “Vile Vitelli.” Cesare Borgia charged him with the task of reducing the city walls to smithereens and opening a way for Borgia’s infantry to assault the city. Having had all winter to prepare, Vitelli’s gunners unleashed a wicked cannonade focused on one of the newly-constructed bastions outside the city walls. It was not long before Vitelli’s gunners had neutralized the bastion. An infantry assault then captured the position. Once that was neutralized and captured, Vile Vitelli had his men mount their guns on the bastion and used this improved position to smash down the walls of the city.

Resistance in Faenza now centered on the citadel of the town. Cesare’s men directed a thunderstorm of fire at the citadel – some 1,600 iron and stone balls – until the fortress was completely smashed up.[22]

Seeing the writing on the wall and unable to bear the suffering of his people any longer, Guido’s cousin Astorre Manfredi sent a messenger to Cesare Borgia offering surrender.

Cesare agreed to generous terms with the people of Faenza, letting them keep their property and allowing Astorre to go free. A few days later, Cesare Borgia reneged on this deal and sent Astorre to the dungeons of the Castel Sant’Angelo in Rome. As was the case for so many men, Astore’s trip to the Castel Sant’Angelo was a one-way journey – he was never to leave there alive.

This was a crucial reminder to Guido Rangoni of what would happen to his family if Borgia conquered Bologna too.

Almost nothing would be heard about Astorre until a year later (on June 9th of 1502) when the Papal Master of Ceremonies noted in a diary that Astorre had been found: “Drowned in the Tiber River, bound to a stone. Two young men and a woman were also found tied to him.”[23] But that was a year in the future.

In April of 1501 immediately after Cesare Borgia conquered Faenza, the Bolognese sent emissaries to offer congratulations to him. Though Bologna had opposed the attack, they still went through with this peculiar ritual of brownnosing. Or at least they tried to.

The emissaries charged to lick Borgia’s boot ran into some of Cesare Borgia’s men on the border between his territory and that of Bologna. Borgia’s men then tricked the emissaries into opening the gates to the fortress of Castel San Pietro, which they promptly conquered. For their assistance the emissaries were thrown into the dungeons, where they could offer their empty flattery to the darkness.[24]

At the same time Borgia’s troops had crossed into Bolognese territory to seize more castles. The invasion of Bologna was on.

Can Hugo, Guido and the Bentivoglio be the first to stop the Borgia juggernaut or will Bologna be the next conquest of Cesare Borgia? Find out in the next installment of Death Before Dishonor—Kill ‘Em All.

See Bibliography for More Details

[1] This was the assassination of Alfonso of Aragon, Cesare’s brother-in-law and father of his nephew first by unnamed assassins and then by Cesare’s henchman, Michelotto Corella. See Lucrezia Borgia by Maria Bellonci, pp. 156-159.

[2] This is a debatable point and contentious among historians. Suffice it to say that there is a lot of drivel printed about Lucrezia Borgia and her father, Roderigo Borgia and many exaggerations of Cesare. Yet there is no other person with a better motive and power to carry out the murder of the Duke of Gandia (Cesare’s brother.)

[3] From his epitaph. See Sabatini, “Atropos.”

[4] Ghiradacci, p. 297. There is no mention of Guido here, but it is a safe assumption that he was there.

[5] Ghiradacci, p. 299.

[6] See Sabatini, “Pesaro and Rimini.”

[7] How to Fight and Defend with Every Kind of Arm, Antonio Manciolino & Jherek Swanger

[8] www.wiktenauer.com, “Fiore Dei Liberi: Mounted Fencing”

[9] Monte, p. 229.

[10] www.condottierediventura.it, entry for “Niccolo Maria Rangoni.”

[11] Specifically, Guido’s uncle (by marriage) Pandolfo Malatesta and his distant cousin Giovanni Sforza of Pesaro.

[12] Ghiradacci p.300. Giovanni “Grandpa” Bentivoglio did the same thing with Guido’s cousin, Alessandro Pio, when his father, one of Bologna’s generals also died.

[13] Sanuto, p.1093-1094. His mother may also have been trying to avoid a trip to Venice.

[14] “Life of Cesare Borgia,” Sabatini, see Siege of Faenza. See also the entry for Guido Torelli in www.condottierediventura.it.

[15] It is supposition that Guido wanted to go fight, given his character and the nature of the situation.

[16] Of course we do not this for sure, but it is hard to see how they would have been playmates and, to a certain extent, friendly rivals.

[17] As to the exiles, Ghiradacci notes that the Senate recalled the “banditi.” There was a long tradition in Italy – as we will see from this series—of exiles taking up arms and functioning as brigands near their old town. Note that Ghiradacci does not say pardons per se, but the giving of pardons is obviously implied since the banditi would hardly be returning to Bologna to face prosecution. The note about Bentivoglio relatives patrolling the city gate is something I read about long ago, but I can no longer find the source. Regardless, basic sense confirms that the guarding of gates would be entrusted to those with a blood tie to the ruling family of Bologna.

[18] Sabatini, “Siege of Faenza.”

[19] See Sabatini, “Astorre Manfredi.”

[20] According to Sanuto, Vol 3, 1381-1382 the campaign was costing the Pope 35,000 ducats a month.

[21] Il Caos by Fantaganuzzi, p.244.

[22] Storia di Faenza, G. Tonducci, p.558.

[23] Liber Notarum, Vol. II. Johann Burkhardt, p.329

[24] Ghiradacci, p. 302.