Bologna seethed under the dominion of the Bentivoglio.

For five long years the Bentivoglio had been in exile, but now, in 1511 Uncle Hannibal was back. He claimed power with the best of intentions. He not only forgave those who had destroyed the Palazzo Bentivoglio, but even put their ringleader, Hercules Marescotti, onto the ruling council of Bologna. The city needed a fresh start free from old grudges, and he told his followers not to exact revenge on those who had helped Alidosi to kill Bentivoglio supporters during the years of Papal occupation.

But no one human was strong to staunch the hatred that had grown like a cancer in Bologna during Alidosi’s reign. Two months after the Bentivoglio took over, there was an incident that put fear into the hearts of all those who opposed the Bentivoglio. “…it was reported that a man named Hieronimo da le Arme was found dead in the street at night, with his hands cut off and his eyes gouged out; it is not known who did it, but he was a great enemy of Bentivoglio.”[1]

Hannibal Bentivoglio also tried to make peace with the Pope, but here he faced an implacable foe. The loss of Bologna was the biggest crisis papacy of Julius II, and out of grief, he grew a mourning beard for the lost city. Hannibal Bentivoglio tried to convince the Pope to let him manage the city on the Pope’s behalf. Julius was having none of it; instead, he traveled north to direct offensive operations against the city.[2]

The Almighty even seemed to be on his side. A month after the Bentivoglio took over in Bologna, a tornado ripped across the countryside destroying everything in its path.[3]

Under pressure from the forces of the Pope the good intentions of Hannibal Bentivoglio came to little. The Marescotti and others began to scheme to help the Pope take Bologna. When Hermes “Dirty Deeds” Bentivoglio discovered this plot, he reacted by killing those found to be against the Bentivoglio.[4] This fear and chaos and oppression drove noble families to the city.

Hugo Pepoli remained on good terms with the Bentivoglio and their oppressive moves would prove to be an enormous opportunity for him.

Lieutenant Pepoli

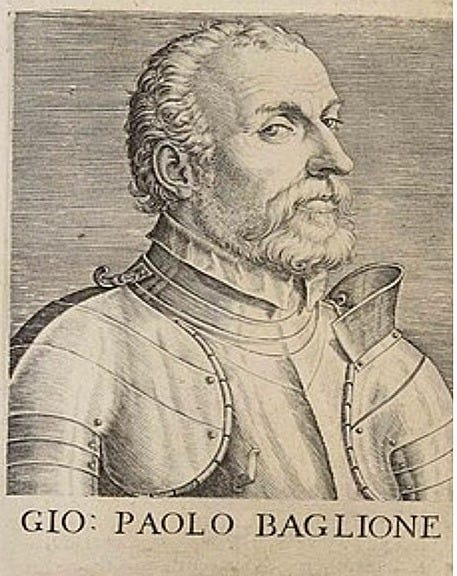

Venice had recruited a new Captain General to replace the late Lucius Malvezzi. To fill this role, they recruited John Paul Baglioni, an experienced condottiere who had been involved in actions against partisans of the Bentivoglio around Bologna. As Captain General of the Venetian army Baglioni would have a company of 200 lances. Baglioni already had about 50 in his service, but he still had to find another 150 or so.[5]

This was a tougher task than it might appear. Men-at-arms were hard to find since they had to be independently wealthy—their equipment was expensive, and their pay hardly covered their expenses. They also had to be skilled in fighting on horseback and on foot with a variety of weapons. Where was Baglioni supposed to find good men at arms? Everyone worth having was already in someone else’s condottieri company. One source was taking men from companies that had lost their commander – in this way he found twenty men-at-arms.[6] That still left him far short of the total he needed to fill out his company.

Exile communities were another source of men, and Baglioni tapped Hugo to lead a squadron of about twenty-five lances.[7] Hugo would then serve as a lieutenant in Baglioni’s companies along with a member of the Fregoso family, the people he had recently helped to escape from Bologna.[8]

Hugo went to Padua to start train up his men. First, he had to inspect their equipment and especially their destriers – the powerful horses that men-at-arms rode into battle. These were enormously expensive, some especially fine destriers cost as much as 1,000 ducats or about as much as a hundred craftsmen earned in a year.[9] A destrier had to be strong enough to run in armor, but more than that, they had to have the kind of violent disposition that made them seek out a fight rather than flee from one. Obviously, such an animal was more difficult to control than a docile one and Hugo had to make sure his men had the skill to master their mounts so that horse and rider could work as one.

Hugo also had to make sure his men had the necessary skill with their weapons. The primary weapon of the men-at-arms was the lance. But it was common to become ensnared in close combat and the men-at-arms then also had to be skilled with the estoc, a thrusting sword that struck into the gaps of an opponent’s armor; the men-at-arms could also use the warhammer to bash an opponent through their armor or hook them and throw them to the ground.[10]

Unlike many foreign knights, Italian men-at-arms had to be skilled at fighting on foot as well as on horseback. For this the preferred weapon was the pole-axe, a weapon that could crush a man’s skull through a helmet, or be used to hook their armor and throw them to the ground, though the best attack with the pole-axe, as with all weapons, was generally the thrust.[11] This weapon was good against opponents both armored and unarmored.

Once his men had the necessary individual skills, Hugo Pepoli also had to make sure his men could work as a group. Depending on the situation, they needed to be able to form up and attack as a body all at once or to break into squadrons and attack in successive waves. To prepare themselves for this moment, Hugo made sure his men-at-arms “followed the call of the trumpet,” and “spent their days jousting.”[12]

Pepoli and Fregoso did such a creditable job with their men that after inspecting the unit in Padua, the Venetian diarist Marino Sanudo said their company, “was worth the value of all our other men at arms put together.”[13]

Guido Rangoni would have disagreed. While Hugo was busy building a company, Guido Rangoni was busy fighting.

The French and German armies were laying siege to Treviso, the northern bastion of Venice’s defenses and Guido had been doing his best to attack their long exposed line of supply. As had happened at Padua two years before, the French were forced to retreat due to a lack of provisions; and so desperate was their plight that they burned all the carts carrying the loot from their rapacious campaign against Venice.[14] Once the French were in full retreat, Guido then traveled north, defeated the Germans and led 200 men-at-arms into the city of Belluno to recapture it for Venice.[15]

Guido Rangoni then returned to Padua for the next phase in the Venetian campaign. He had been successfully fighting for the past two years, yet in prestige, he found himself barely ahead of Hugo Pepoli. Competition for prestige among the various companies of men-at-arms was always present whenever the army camped, and the company of Baglioni, leader of the Venetian, were naturally the top dogs. And since Hugo worked closely with the Captain General and often spoke for him, this gave him an importance that must have irritated someone like Guido Rangoni who had climbed the ladder of success one bloody rung after another.

Still one good thing about being with Hugo Pepoli is that both men could share information about what was happening back in Bologna, even if the news was bad.

The Finest Army in Europe

There was a new player in Northern Italy. The King of Spain[16] had sent a powerful Spanish army into Northern Italy on behalf of Pope Julius. While this would eventually prove to be an even greater concern than the presence of the French, the fall of Bologna had made Julius desperate.[17] For the people of Italy the Spanish were an even greater terror than the French. They descended upon enemy towns like a plague of death.

Here is a description of the Spanish sack of Prato, a city near Florence.

“… those who were unable to escape, threw down their arms, and kneeled with their arms crossed in mercy before the attackers [but] were cruelly cut to pieces. The great church of Prato called the Pieve sheltered two hundred behind locked doors, and when the enemy entered, they attacked a crucifix, killing the person who held it and lopping off one of Christ’s arms before massacring everyone and leaving a pool of blood to spread over the pavement. Similarly, every person who sought refuge in the church of the Vergine was killed, both women and the husbands and sons whom they embraced, as well in San Domenico, Sant’ Agostino, and other holy places.” [18]

Not only was the Spanish army the most savage in Italy, but it was also probably the best. The pendulum between the dominance of infantry and cavalry was swinging back in the direction of the foot soldier, and here lay the strength of the Spaniards. The quality of their footmen was no accident.

Already in 1495 the Spanish had recognized the growing importance of firearms and in the infantry ordinances of Valladolid issued by the King and Queen of Spain, they had decreed that infantry would be composed of one-third pikemen, one-third sword and shield men, and one-third musketmen.[19] The pikemen were critical against cavalry, the sword and rotella men were used in tight quarters once against other blocks of pike, and the musketmen gave the infantry forces the ability to strike at a range. It was just such a force that had sent the French running from the Kingdom of Naples like so many scared little girls some eight years before.[20]

But it was not just in organization that Spanish held an advantage. In places like France, there was no tradition of infantry service and the general contempt of the lower classes made it hard to arm them and incorporate them into functional military units while in Spain there was a professional class of infantry soldiers.[21]

The Diggers

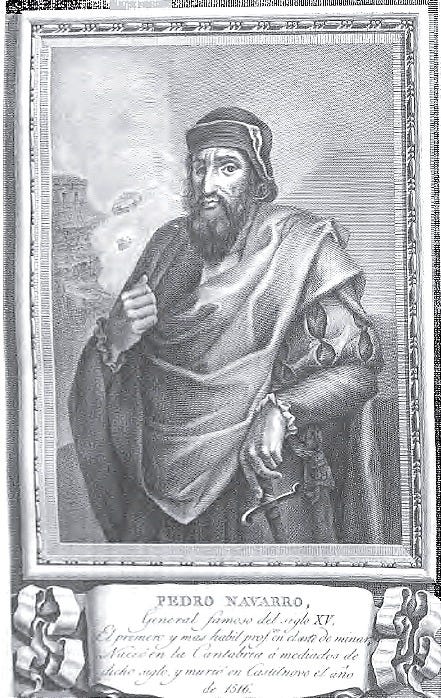

The Spanish started their foray in Northern Italy by attacking the fortress at Zaniolo that had stymied the Pope and the Venetians for so long. This was the fortress that would open an attack on Ferrara. By tunneling under the walls and blasting the foundations with gunpowder, their general Pedro Navarro managed to capture Zaniolo in a matter of days.

Rather than pressing on to Ferrara, the Pope now sent Pedro Navarro and his plague of death towards Bologna. To keep them from looting the Venetian countryside, the Republic of Venice ordered Guido Rangoni to escort them.[22] This was a bitter mission for Guido Rangoni. This Spanish force was powerful with 800 lances of heavy cavalry (Italian and Spanish), 1,700 light cavalry, 13,000 Spanish infantry as well as 6,000 Italian mercenaries, including the hated Ramazzotto.[23]

Guido could hold out little hope for his relatives. To defend Bologna, they had 300 French lances, a few veteran soldiers and the people of Bologna.[24] It was hard to see how they could stand up to the mighty Spanish force for very long. Their only hope lay with the new French commander in Italy the young man known as the Thunderbolt.

The Bentivoglio had to depend on the people of Bologna but how would they act? Reports beyond Bologna claimed that they were unhappy with the Bentivoglio. The Venetians were sure the Spanish would need only show up for the people to drive the Bentivoglio from the city.[25] But Guido knew his people and knew that despite their squabbles they tended to band together against outsiders.

The Spaniard and the Venetians soon learned this, too.

The Siege of Bologna

As soon as the Spanish army arrived outside Bologna some allies of the Bentivoglio joined forces with the French cavalry and launched a surprise attack on the Spanish, only retreating after realizing how outnumbered they were.[26]

The people of Bologna were prepared to fight. They called for help from the French, hunkered down behind their walls and prepared for a siege. The Bolognese came out to protect the Bentivoglio including people connected to the Bolognese School of Fencing; there was a member of the Marozzo family as well as members of the Dalle Agocchie family. Maestro di Luca, the man who had taught Guido Rangoni and Achille Marozzo the use of the sword, also sent his son to fight for the Bentivoglio.[27]

The Spanish were confident – General Navarro boasted he could conquer Bologna “in four hours.”

Navarro brought up their artillery and emplaced in the night to protect it from Bologna’s own cannons. Unlike Padua, the city of Bologna was still protected by tall medieval walls instead of the squat walls preferred for modern defenses. When the Spanish artillery unleashed a barrage on the walls of Bologna the next day, they quickly opened a breach in the walls so wide “that a cart could pass through it.”

Navarro sent infantry to assault the city. The Spanish approached behind their yellow banners as the artillery of Bologna laced lanes of death through the Spanish ranks. The Spanish made it to the breach, quickly drove away the Bolognese militia present, and then planted three Spanish flags on the breach. The way into Bologna was wide open.

One of the Bentivoglio’s infantry captains now led a company against the Spanish. He was known as Spinazzo and had fought against the Spanish at Padua, defending the walls around the Bastion of the Cat.[28] As he rode towards the intrusion with his men behind him, he shouted at the fleeing militia men and told them to return to their post. Upon reaching the breach where the Spanish, “were boldly entering through the opening,” Spinazzo and his men, “repelled them with great courage, seizing their flags and killing the standard-bearers along with over thirty Spaniards, losing only three of his own men.”[29]

The Bolognese were determined to defend the city from the Spanish but that did not stop the Spanish from trying. Their cannons destroyed the house of the Bolognese fencing master, Antonio Manciolino, and also collapsed a section of the wall on the southeast corner of the city. Still though their artillery made life in the city difficult, they dared not assault the walls and go sword to sword against the people of Bologna.

The Miracle

Navarro had an ace up his sleeve. While his cannoneers blasted Bologna, General Navarro’s engineers rapidly dug a tunnel towards the south-eastern side of the city, aiming at a little church just inside the walls.

This led to one of the more interesting escapades of the siege.

“The Spanish delayed launching a full assault on the city, as they were waiting for the completion of a mine. This work was being handled by Pietro Navarro, a renowned expert in such operations, who had previously caused significant harm to the French in the Kingdom of Naples.”

“The city's defenders, realizing this, sought to discover where the enemy was digging so they could counter-mine and create an airshaft, which is the only remedy against such tunnels. Since they couldn't detect the exact location by sight, they used a clever and elegant method. They placed several copper basins along with many war drums—each fitted with bells—on the ground along their side of the walls. The vibrations caused by the enemy’s digging made the bells on the basins and the drums ring, revealing that the tunnel was being dug beneath the Madonna del Baracano.”

“Once they realized this, they brought many drilling tools, like those the Bolognese commonly use for digging wells, and drilled into the ground in several places. They found the mine and not only discovered the tunnel but also the barrels of gunpowder that filled it. They then created several airshafts, all leading to the mine, and without disturbing it further, they waited for the enemy to ignite the gunpowder and see the explosion fail.“

“The Spanish, having placed great hope in the mine, began tightening the siege with frequent assaults, putting the city in great fear. Eventually, they set the mine on fire, and although it exploded with much terror for those inside, the chapel of Baracane, despite being lifted from its foundations by the force of the explosion, almost miraculously returned to its original position.”

“Thus, the mine yielded no result, to the great surprise of the Spanish, who had expected massive destruction…” [30]

“The blowing of the mine was to be timed with an assault on the southeast side of the city. But to the Spanish and the Bolognese, the way the church fell seemed like an act of the Almighty and it gave heart to the Bolognese while frightening the Spanish.”

The Spanish were now in for an even bigger surprise.

The French had not forgotten their ally. Their new General in Italy, the Thunderbolt, rapidly gathered all the French troops he could lay a hand on, then marched them across Italy with a speed that none could anticipate. On the last day he took his army on a forced march of thirty miles across a snow-covered land. The Spaniards were not aware of the approach of this French army until they walked in through the Spanish lines.

The French entered the city of Bologna on the north side while Spanish were camped to the south.[31] Spirits inside the city soared and Bologna threw open its gates, daring the Spanish to come out and play.

The Spanish refused the invitation. Even though the Spanish outnumbered the combined Bolognese-French force they slunk off to the east, away from danger.[32]

Bologna was safe for the Bentivoglio once again.

The Thunderbolt was young and hungry for glory. He wanted to lead his troops against the Spanish army and whip them, but events elsewhere now drew him away from the Spanish. Instead, he was going to be heading north, directly at Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli.

Find out what happens when Guido and Hugo had to fight the Thunderbolt in our next episode, “One Shot At Glory.”

[1] Sanuto, XII, col. 291

[2] Julius II, Shaw p.277.

[3] Sanuto, XII, col. 243. He notes a great storm that struck Bologna and destroyed everything. While tornadoes are not common in Italy they do occur. It is possible it was just a rainstorm but one that just affected the area around Bologna, though it is not mentioned as doing any damage in Modena, a short distance from Bologna.

[4] See www.condottierediventura entry for, “Hermes Bentivoglio.”

[5] That is the number he commanded in the Papal service. Some men may have stayed and joined the company of his son, Malatesta Baglioni, but the number was not likely a large one; in the winter of 1510-1511 Malatesta Baglioni had 9 men at arms under his command and a year later the number had grown to 25 (as a nominal amount.)

[6] Sanuto, XIII, col. 110. This was the former Papal condottiere Gianfrancesco di Conti.

[7] This is a simplification. The fuller situation seems to be that Romeo Pepoli was involved in the recruiting of the Bolognese men at arms in October of 1511, and even went to Venice for the ceremony where Baglioni took command. Romeo’s association with the company seems to stop at this point. He probably helped Hugo when Hugo was left alone with the company and lent his prestige to Hugo but was probably tasked with running Baglioni’s light cavalry.

[8] This was probably a different Octavian than the Octavian who was in charge of the citadel of Bologna and who left the city when the city fell to the French and the Bentivoglio. This Octavian (Ottaviano di Agostino) was the leader of the exiles and future Doge and would have been too important for such a menial job such as minding a citadel.

[9] Sanuto, Vol IX, col. 39-40: “then I saw a beautiful horse called Favorito, which I valued at more than 1000 ducats, which belonged to Zitolo…”

[10] The use of both these weapons is described in Monte, Forgeng, pp.205-209.

[11] See Monte, p. 67.

[12] See the Warbook of Orsino Orsini for descriptions of proper training of knights.

[13] See www.condottierediventura.it entry for “Giampaolo Baglioni.”

[14] See Sanuto, XIII, col. 106, 113, 117.

[15] See www.condottierediventura.it. Entry for “Guido Rangoni.” The Venetians soon had to abandon the town due to Baglioni’s leadership.

[16] Note that Ferdiand II (1479 -1516) was not actually the King of Spain. He was King of Aragon and married to Isabella, Queen of Castille. So, he was not technically the King of Spain, but was called so at the time, and is called such for convenience in this work.

[17] Julius II, Shaw p.305.

[18] Get direct quote from Storia Fiorentina.

[19] Shaw & Mallett, pp. 286-287.

[20] Note this was after some small reformations had been made to the Spanish army after an initial defeat against the French and Swiss at Seminara. Thereafter, the Spanish made a point of equipping their infantry with the standard ‘heavy pike’ (15-18 ft. long) being used by the Swiss and other infantry forces.

[21] It was to these that the infantry ordinances addressed themselves. See La Revelucion Militar Moderna.

[22] Sanuto, Vol XIII, col. 379 for some reason the Spanish army went by way of Vicenza and then through Mantua.

[23] According to Sanuto this was 1,800 lances of heavy cavalry (Italian and Spanish), 1,700 light cavalry, 13,000 Spanish infantry as well as 6,000 Italian mercenaries under the pay of the Spanish crown. In addition to this was 4,000 and Ramazzoto the Priest had another 4,000 Italian mercenaries in the mountains. Sanuto, Vol XII, col. 399. See also Pompeo Vizzani p. 498.

[24] Guicciardini also mentions there being “2,000 Landsknechts and 100 French Lances,” in his description of the siege on pp. 962-970. But these appear to have been dispatched by the French but failed to reach Bologna before it was encircled by the Spanish.

[25] Sanuto, Vol XIII, col. 367.

[26] Vizzani, p.498.

[27] See dalle Tuate. For more see. www.substack.artofarms/AchilleMarozzoUncovered.

[28] See Sanuto, Vol IX, col. 237. There was a “Spinazo da Bologna,” under the command of Zitolo of Perugia at Padua. It’s possible this could refer to another Spinazo, but this seems highly unlikely as this is an unusual name.

[29] Vizzani, p.500.

[30] Da Porto, p.252. As unbelievable as this story sounds variations of it appear in Sanuto, Guicciardini and Vizzani.

[31]Mallett & Shaw, p. 117. See also

[32] Vizzani, p.501.