He was coming back.

In 1501 Cesare Borgia had invaded the territory of Bologna but the Bentivoglio stopped his army. Then the two sides had signed a peace agreement. This being Renaissance Italy, all parties understood the deal was really nothing more than a short term ceasefire. By the summer of 1502 rumors started circulating that Cesare Borgia was preparing to invade Bologna once again. Cesare needed a large city with a rich cultural heritage to be the capital of his Dukedom of Romagna and Bologna fit the requirement nicely.[1]

To test the truth of these rumors Grandpa Bentivoglio sent an ambassador to meet with Cesare. The Duke confirmed he intended to drive the Bentivoglio from the city. When the Bolognese ambassadors replied this would mean war with Bologna, Cesare responded with a threatening look.[2] He then said, “Soon the Bolognese would realize how mistaken they were to think they could oppose him and how wrong they were to support the tyrant Bentivoglio against all reason.”[3]

The hold of the Bentivoglio family on Bologna depended on the city senate. The city senators now met to discuss whether to fight Cesare or to drive the Bentivoglio family from the city and surrender themselves to the Duke. The previous year, Guido’s uncle Hermes Bentivoglio had led a band of bloodthirsty youths on a wholesale slaughter of the Marescotti family, and resentment against the Bentivoglio simmered. On the other hand the people of Bologna hated the Vatican, and thought Cesare, “full of arrogance and unbearable pride.”[4]

Any doubts as to the course of action were dispelled by the appearance of Hugo’s father, Count Guido Pepoli. Standing before the Senate with his sons and followers, this “highly esteemed man” with “a long face, aquiline nose, lively eyes, and a dignified appearance” now spoke on behalf of his friend Giovanni Bentivoglio.[5] He reassured the Senate, “we are fully capable not only of defending ourselves against Cesare Borgia but also of attacking him. Be assured that this [battle] will be nothing more than a gust of wind or a flash in the pan."[6]

What Cesare did not understand was how ready Guido Rangoni, Hugo Pepoli and the people of Bologna were to meet his forces. Grandpa Bentivoglio had spent the previous year feverishly adding fortifications around Bologna as well as finding troops willing to fight under the banner of the Bentivoglio.

The Bolognese then sent a pair of stalwart-hearted ambassadors to tell Cesare it was best to leave Bologna alone. These ambassadors warned the Duke, “We will not wait for you to lay siege within the walls but will instead come out armed to meet and assault you wherever you may be. And we will respond in such a way that you will regret not leaving us in peace.”[7]

The Pope responded by declaring war on the Bentivoglio. Though Bologna was under French protection, the King of France declared that his protection applied only to the members of the family and that Bologna itself belonged to Rome.[8]

The Bentivoglio expected the attack to come from Cesare’s base at Imola. If the Duke of Romagna tried to attack on the southern flank through the mountains, the Bolognese had this protected. They had converted a convent along the mountain road from Imola into Bologna into a great fortress.[9] They placed this fortress under the command of Mancino da Bologna, the greatest swordfighter of his age.[10]

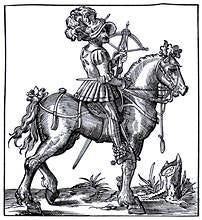

If the Duke tried to follow the previous year’s plan and attack around the northern flank into Bologna, the Bentivoglio were prepared for this as well. Grandpa Bentivoglio had improved the defenses of Budrio and Medicina. To give these fortresses the ability to sting as well as defend themselves, he sent some 250 mounted crossbowmen in Bolognese livery to use these fortresses as a base.[11]

These defenses would force Borgia to attack directly from the east. Here the Bolognese stationed young Guido Rangoni, with his company of men-at-arms. With him were the rest of the main forces of Bolognese army all under the command of uncle Hannibal Bentivoglio. Hugo and the rest of the Pepoli were also out in force, leading a large group of infantry from the mountains above Bologna.[12] The army was partially motivated by a love for the Bentivoglio; but even those opposed to the Bentivoglio, like the diarist and historian Filena dalle Tuate, were happy to take up a sword against Borgia because they hated the corrupt church so much, “that they would have taken sides with Satan himself against the men of the pope.”[13]

Hugo, Guido and the Bolognese would not get the chance here to defend their territory against Borgia’s men, for the Bentivoglio were now finding powerful allies.

Cesare Borgia had made much use of careful and calculated betrayal to build his Duchy of Romagna.[14] This caused condottieri like Vile Vitelli to believe that Borgia would soon betray them and take their lands for himself.[15] Grandpa Bentivoglio sent uncle Hermes Bentivoglio to meet with these condottieri. Uncle Hermes suggested that the generals assassinate Cesare Borgia, but they balked at such a dishonorable deed. Instead Borgia’s condottieri formed an alliance with the Bentivoglio to attack the Duke’s lands.

These condottieri then betrayed the Duke and defeated one of his armies and word soon spread of the magnitude of this defeat. Near Borgia’s capitol, “twenty carts full of the dead and the living passed, remnants of the battle.”[16] Cesare Borgia now retired to his fortress at Imola, a city only twenty miles from Bologna. There he planned to hunker down and wait for relief.

So on October 21st Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli, with pennants fluttering from their lances, rode to the border with Imola. They, and the rest of the Bolognese army reached the border and found no enemy force to bar them. The army was strong with some 1200 cavalry and 6000 foot. They even had six cannons to use in battering down enemy walls. The commander of the army, Uncle Hannibal Bentivoglio, now faced a choice: take bold action and invade Borgia’s territory or wait for Borgia’s condottieri to make the march north from Fossombrone.[17]

Young men like Guido and Hugo would have urged Hannibal towards decisive action, but Hannibal was loathe to violate the previous year’s agreement with Cesare Borgia. The Duke was an ally of the King of France, and it was not yet clear how the King would react to this attack on an ally.

Hannibal decided on a half measure. On October 22nd he sent Uncle Hermes and the light cavalry forward.[18] Shouting the traditional war cry of Bologna, “Sega! Sega!” the mounted crossbowmen rode across the narrow stream that separated the territory of Bologna and Imola. The armored cavalry and infantry could only look on with envy. Hermes’ light riders raised Hell around Imola, “seizing numerous animals, including the Duke’s own mules.”

By dithering the Bentivoglio would miss their chance to attack the Duke. On the same day that Hermes’ men crossed into the territory of Imola, four hundred infantry marched into the Duke’s fortress, giving him enough strength to resist any attack by the Bolognese.[19] Though his fortress was secure, Cesare Borgia was powerless to stop the humiliating raids on his territory. He could only wait in his fortress, watching and recall the prophetic words of the Bolognese ambassadors: “You will regret not leaving us in peace.”

All now awaited the King of France. What would his position be on the revolt of the condottieri and the attack of the Bolognese?

They need not wait long. Messages soon came from the King of France that he disapproved of the actions of Bologna against Cesare Borgia.[20] This was hardly a surprise to the Bentivoglio. But word soon came of more decisive actions. The King was sending 3,000 Gascon crossbowmen to reinforce the position of Cesare Borgia.[21] Then on the 29th came word that 1,600 French cavalry were passing through nearby Ferrara en route to Imola.[22]

Grandpa Bentivoglio and Borgia’s former condottieri were forced to make a rapid re-calculation. At that time the French in Milan were the most powerful piece on the chessboard of Italy. Grandpa Bentivoglio made a new alliance with Cesare Borgia to be sealed by a marriage between the Bentivoglio and Borgia family to seal the deal. The Duke would respect the territory of Bologna and in exchange the Bolognese would pay a hefty fee of 1,000 ducats per month to support the army of Cesare Borgia – a levy that would bring much hardship on the people of the city, especially after their recent military expenditures.[23]

The Bolognese Army returned to the city, “without having achieved anything.” It was a crucial lesson to both young warriors Guido Rangoni and Hugo Pepoli: “In war only the bold could achieve success.”

Cesare Borgia made a show of forgiving his rebellious condottieri and accepting them back into his service. He waited a few weeks to allay their suspicions, then seized almost all of them at once on New Year’s Eve of 1502. There he had Vile Vitelli and the others strangled to death with a violin string. Only the clever condottieri John Paul Baglioni escaped his wrath.[24] Years later Hugo Pepoli would serve directly under Baglioni and he would play a pivotal rule in causing the duel between Hugo and Guido.

Cesare also tried to take out Grandpa Bentivoglio by employing his French allies. As the French army was passing by Bologna on the way from Imola to Milan, the Bentivoglio received the French general in the city with a great parade. There they feted him in the best style of the time. When it was time to leave the French general tried to lure Grandpa Bentivoglio out of the city, where he planned to have his soldiers seize Grandpa Bentivoglio.

But Grandpa Bentivoglio had survived decades at the summit of Italian politics and multiple assassination attempts, and was not be outfoxed by a Frenchman -- he refused to accompany the French leader beyond the walls of Bologna. Instead of following the custom of the time to escort the French general from outside the city, Grandpa bid him adieu from the Bolognese side of the walls and saved himself from the kidnapping.[25]

This was how “allies” treated one another in Renaissance Italy.

The Borgia would never succeed in getting the Bentivoglio out of Bologna. While Cesare Borgia never gave up his intention to take the city, his plans became seriously derailed when his father became ill. As the story went in Italy, as the Pope lay dying, “The devil was seen to leap out of the room in the shape of a baboon. And a cardinal ran to seize him, and, having caught him, would have presented him to the Pope; but the Pope said, ‘Let him go, let him go. It is the devil,’ and that night he fell ill and died.”[26]

The news reached Bologna on November 4, “and by order of the senate, the city celebrated with fireworks, music, and artillery. Grandpa Bentivoglio now allied Bologna with the lords whose lands Cesare had taken, many of whom were relatives. He also sent Hermes Bentivoglio with 100 mounted crossbowmen to provide an escort for Cesare Borgia’s most hated enemy, a churchman from the windswept shores of Liguria.[27] This stubbon, irate man, a cardinal, was named Giuliano della Rovere. He had the money and the prestige to become the next Pope and he hated all things Borgia.

After months of haggling, fighting in the streets of Rome, skullduggery and a three week papacy of another candidate, Giuliano succeeded in becoming Pope Julius II. Pope Julius promptly betrayed Cesare Borgia and forced him to flee to his ancestor’s homeland in Spain.

There was much celebration in Bologna over the new Pope who had once been the Bishop of Bologna. Grandpa Bentivoglio was eager to be on good terms with the new Pope. In early 1504 Cesare Borgia tried to smuggle a load of treasure through Bolognese territory including, “Saint Peter’s cross adorned with precious jewels, Saint Peter’s cloak with jewels and fine gold threads.” These relics were worth a king’s ransom; the Bolognese seized the cargo and brought it to Grandpa Bentivoglio.

Rather than keep it, or sell it, Grandpa Bentivoglio had the treasure returned to the new Pope.[28]

Bologna was secure.

The way was now open for Guido and Hugo to become mercenaries. Follow their adventures in our next episode, Swords for Hire.

[1] You could make the argument that this did not apply to Urbino, which the the Montefeltre Dukes had embellished with great art. However Urbino’s cultural significance was directly tied to its Dukes and their court and was not an intrinsic part of the city since Urbino was itself was relatively small—the modern town of Urbino has far fewer people than even the poulation of medieval Bologna. Without the Montefeltre Urbino thus had little on its own to offer.

[2] For sake of ease this story has been slightly altered. As Ghiradacci discusses on pp.312-314 the Bolognense originally sent, “Senator Giovanni Francesco Aldrovandi as an envoy to determine the Duke’s intentions toward Bologna.” But then they decided he was excessively timid and sent two other ambassadors, “Carlo Ingrati and Jeronimo da San Piero, both knights and senators.”

[3] Vizzani, pp. 445-448

[4] Vizzani

[5] Ghiradacci, p.339.

[6] See Ghiradacci, p.314. Note that these words were originally those of Dionosio di Luca. According to Ghiradacci Count Guido Pepoli echoed these words.

[7] Vizzani. Note that Vizzani used third person for this and I have opted to translate it to second person for this work.

[8] Sabatini, “Revolt of the Condottieri.”

[9] Bernardi, II, p.34. Ghiradacci, p.315.

[10] www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Mancino da Bologna.” He is described as “the greatest fencer then in Tuscany.” See also Camillo Palladini, Terminello and Pendragon, {p.?} where Mancino da Bologna makes an honor roll of the greatest swordfighters in Italian history.

[11] Ghiradacci, p.312. Later in the series we will take a look at the surprising effectiveness of mounted crossbowmen as raiders.

[12] The disposition of the Pepoli is supposition. It seems more likely that they would have operated separate from the professional companies of condottieri, given both their prestige and their resources. Since the Bolognese mountain forces were known as some of the finest infantry and the Pepoli were influential among these, it seems most likely that you would find Hugo here.

[13] See Sabatini “Revolt of the Condottieri.” I have substituted “men of the pope” for the awkward, “pontificals.”

[14] In particular the Duke of Urbino.

[15] In this case of Vile (Vitellozzo) Vitelli this was also compounded by Borgia’s lack of interest in another campaign against Florence. He was strongly motivated by a desire to avenge the execution of his brother, the condottiere Paolo Vitelli. See www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Vitellozzo Vitelli.”

[16] Sanuto, I Diarii, Vol iV, col 384

[17] See Ghiradacci, p.317.

[18] We do not know that it was under the command of Hermes Bentivoglio, but in most operations of the Bolognese army around this time, Hermes ends up commanding light cavalry.

[19] Sanuto, IV, col.388. See also www.condottieridiventura.it entry for “Lucio Malvezzi” Oct 1502.

[20] See Ghiradacci, p.317, “On November 4, a French herald arrived in Bologna, relaying the King’s discontent with Bologna’s alliance with the Orsini and Vitelli against the Duke, urging peace with the Pope. The Senate respectfully dismissed him without committing to any position.”

[21] Sanuto, IV, Or to put it more accurately the King was conseting to Borgia hiring 3,000 Gascons for his army. Note that in this section it is not specified that these are predominately crossbowmen, but other works, especially Giovio’s History of His times are clear that the Gascons are primarily arbalasters.

[22] Sanuto, IV, col.410.

[23] Ghiradacci p.322

[24] See Sabtatini, “The Beautiful Stratagem.” This is an easy read in English of Cesare Borgia’s (mis)deeds.

[25] Ghiradacci, p. 319.

[26] Life of Cesare Borgia, “Death of Alexander VI”

[27] The Warrior Pope by Christine Shaw, p.117

[28] Ghiradacci, p.329