“And so, we have taught and given the knowledge of the gallant guards that pertain to this ingenious art of defense, for there is nothing in this art that you need to understand more readily. This way when you find yourself against an enemy, you can immediately identify how the swords are placed, for the attacks one may make with the sword are infinite and innumerable, and so too are the ways in which a sword may be found; yet from one guard to another, not all attacks will be suitable, and by being shrewd, and also being illuminated in the knowledge of your enemy’s placement, you will make effective attacks, in the correct tempo, using your sword and your body; and by making attacks in this manner you will remain secure from harm.”

-Anonimo Bolognese

As the anonymous author of MSS. Ravenna succinctly points out here, knowledge of the guards; in how they’re formed, how they defend, and how you can attack from them, can unlock the deepest mysteries of art of swordsmanship. However, knowing what you can do in the guards is only half of the payout, because developing this depth of knowledge and insight will allow you to read your opponent’s intentions as well:

While you and your opponent are studying each-other, never stop in a particular guard, but change immediately from one guard to the next. This will make it harder to judge your intentions.

-Manciolino

And once again to the anonymous author:

“So that the art will become clear to you, I’ll add that if you face an armed opponent, you should make a point of keeping your eyes on his weapon hand…by watching the movements of his sword hand, you may deduce all his designs…”

-Anonimo Bolognese

I’m starting with these quotes specifically because they bring to bear the importance of the guards in the Bolognese pedagogy. This is the foundation of the art. There are a few different ways to approach this, so if one of these approaches doesn’t work for you, or seems overwhelming, you’ll be able to try the other. The beauty of having so many different authors to choose from, with such a variety of approaches is, they’ll often afford diverse paths that will inevitably lead to the same outcome. If you are the kind of person who needs detail first, you need to know how things work, dig into Marozzo’s chapters 138-144, and supplement the offenses and defenses that Marozzo suggests but never explains with Manciolino’s Chapter 1 material—this is the Guard Focus approach. If an overload of information will short circuit your hard-drive, and you just need the why, then focus on the Tactical Approach first. Eventually you’ll have to understand both; ie. you’ll need both the how and the why. For the purpose of this article, I encourage you to look at whichever section speaks to you first, then go back and study the other, for the sake of completion. I’ve tried to organize this information in a way that I think is coherent for both—let’s hope it works.

The Guard Focus will take you guard by guard, following Marozzo’s chapters 138-144, give you a quote from Manciolino and Marozzo on the nature of the guard, and a brief tactical synopsis. Again to really get the meat of this detail, you’ll have to follow the fullness of Marozzo’s advice, and that’s to learn how to perform every viable attack and defense from each of the named guards, and the only time this is laid out in a complete way is in Manciolino’s Chapter 1. You could theoretically follow dall’Agocchie here, but I would avoid confounding dall’Agocchie with the earlier authors, though you might need his Guardia d’Alicorno material.

The other means of approaching this is the Tactical Approach, this is the ethereal approach to understanding. If you haven’t watched Jake Norwood’s amazing lecture on Liectenauer’s approach to the fight, where he breaks down the KdF system into OODA Loops, you should check it out. This approach is in no way asynchronous from what we see presented by the Bolognese authors, and I’ll wrap up the tactics section with a quick tool I use for the observation portion of things. As verbose and wordy as the Bolognese authors can be at times, sometimes they rely quite heavily on simple defining concepts, and I think this provides two approachable pathways for variable means of conceptualization.

Without further ado, en garde!

Guard Focus:

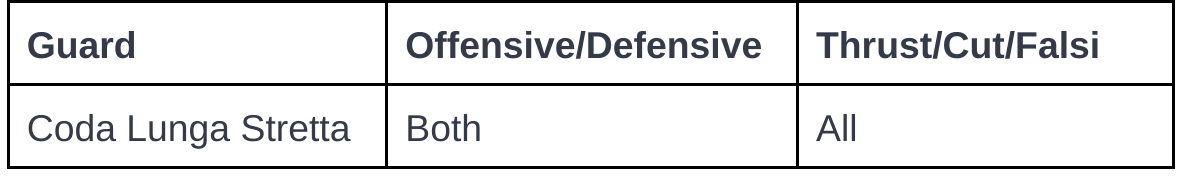

Coda Lunga Stretta:

Marozzo: This is called the coda lunga e stretta, and it is equally good for attacking as it is for parrying. Therefore, with your student in this guard, show him how many attacks he can do when he wants to be agent, and then, as patient, show him how many parries can be done, both high and low, varying between the two; and when you present him the parries also present him the attacks in the forms in which they will happen to him, having him return to this same guard of coda lunga e stretta every time once he’s attacked and parried. Do this until he’s learned all the attacks with their parries, and likewise all the parries with their attacks.

Manciolino: It bears its name from the common proverb “do not embroil yourself with great masters, for they have a long tail,” that is, they have the power to injure you by means of their numerous followers. So, that guard gave the name to this ninth and to the tenth, along with their great suitability to reach and strike the opponent.

Cinghiara Porta di Ferro:

Marozzo: From here, begin to examine your student regarding the aforesaid guard, and make him understand that whenever he is in the said guard, he will be constrained to be patient, considering that all of the low guards are more for parrying than attacking; and if he wanted to attack rather than parry, you know what the only attack he could use is the thrust, or some falsi. Therefore show your student how, if he is in this guard and someone attacks him with the mandritto, riverso, stoccata or thrust, high or low, he must parry and then attack, whatever the situation, counseling him that he should parry with the false edge rather than with the other one, because it will be more useful than parrying with the true edge, since as you know, with a falso one can strike and parry in the same tempo. And whether he steps forward with his right leg, or sends it to the rear, as with all the guards, always have him return in cinghiara porta di ferro stretta.

Manciolino: This guard is called Cinghiara (wild boar) after the animal bearing that name, who, when attacked, sets himself with his head and tusks sideways in a similar offensive guard.

Guardia Alta

Marozzo: Therefore in God’s name you will begin to show him how many attacks can originate from guardia alta, with their parries, making him understand that this guard is primarily for attacking; and then you will show him the parries, with their attacks, stepping forward and back every time, depending on the situation, always remembering to have him return into said guardia alta once he parried or attacked.

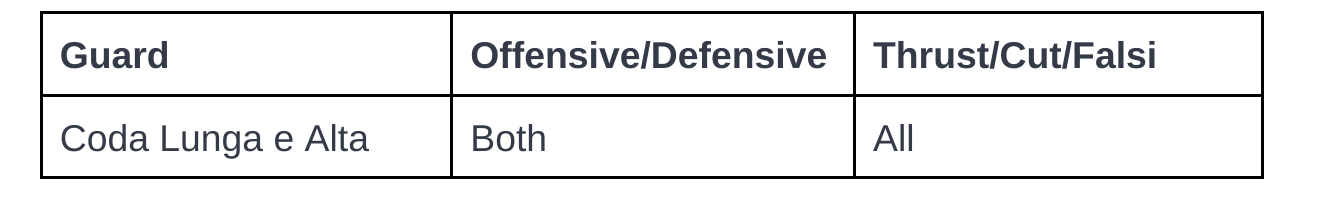

Coda Lunga e Alta

Marozzo: I want you to know that this is a good and useful guard in which to be patient, and for this reason you should tell your student that if he finds himself in some quarrel, that he must adopt this guard first when facing his enemy, for his defense, and make him understand what he can do therein, pro and contra, in every manner possible. For all this, you will show him how many parries can be done against a punta or a stoccata, and likewise against mandritti and riversi, and also against falsi. Every time you show him these parries, also show him the attacks that follow them, having him step forward or back according to the circumstances, and always returning into the same guard, with some attacks or some parries.

Manciolino: It bears its name from the common proverb “do not embroil yourself with great masters, for they have a long tail,” that is, they have the power to injure you by means of their numerous followers.

Porta di Ferro Stretta, or Larga

Marozzo: That his sword would fall in porta di ferro stretta, or larga, and moreover, that he would have to be patient. I wanted him to stay fixed in that guard because it seems to me that one who is in porta di ferro stretta, or larga, cannot do too many attacks, but I tell you truthfully that quite a lot of parries can be performed, namely falsi, with mandritti or riversi of such nature as seems best to you, or one can parry in guardia di Faccia, or Guardia di Testa, or in some other fashions that I’ve taught you. Such things as can be done in Porta di Ferro stretta or larga can also be done in cinghiara porta di ferro, for the most part.

Manciolino: This guard is called Porta di Ferro Stretta by virtue of being safer than the others and of iron-like strength. Unlike in the Porta di Ferro Larga, which we will see next, in this guard the sword is held tightly close to the opponent while keeping an equally tight defense of the right knee.

Coda Lunga e Distesa

Marozzo: With your student in this guard, make him be agent, specifically with falsi dritti, or with thrusts and riversi or other blows that can originate from the said guard, and with the parries that follow them. See that you always present your student the parry along with its attack, and bring him to understand the manner and the way in which the aforesaid attacks and likewise the parries must be performed, and in what place, for attackinging is nothing so great, but knowing how to parry is a finer and more useful thing; for man knows by nature how to attack, but not how to parry.

Guardia di testa

Marozzo: In the said guardia di testa, he can be agent or patient, but first we will discuss being patient. Being patient, if the enemy throws a mandritto fendente or a mandritto sgualembrato, or a dritto tramazzone, your student must parry any of these blows in guardia di testa. But if you want him to be agent from said guardia di testa, tell him that he can be agent by throwing an imbrocatta dritta, overahand; or a mandritto fendente, or tondo, or sgualembrato; or a falso dritto, following the blows with a riverso in whatever manner is convenient.

Guardia d’intrare

Marozzo: Make him understand that lying in this guard it will behoove him to be patient, since, if I recall correctly, I’ve shown you that few attacks can originate from such a guard if you were to wish to be agent rather than patient.

Coda Lunga e larga

Marozzo: Now make them see, and show them the pro and contra of what can be done when being agent, and then when being patient. And note that one can be either of those in this guard, because from here one can throw a falso and riverso, a tramazzone dritto and falso, or a tramazzone riverso and a false edge tondo, returning the sword to its place with a riverso sgualembrato. One can also throw imbroccate; or punta infalsate, either dritte or riverse, fallaciate or not, along with the riversi that are pertinent according to the kinds of mandritti they throw.

Manciolino: It bears its name from the common proverb “do not embroil yourself with great masters, for they have a long tail,” that is, they have the power to injure you by means of their numerous followers. So, that guard gave the name to this ninth and to the tenth, along with their great suitability to reach and strike the opponent.

Becca Possa (Guardia di Lioncorno)

Marozzo: Advise him that he must go into this guard if his enemy were to go into porta di ferro larga, stretta, or alta, following him step by step, from guard to guard; that is, if he were in coda lunga e distesa, have him go into becca cesa; and if he were in coda lunga e larga, have him go into coda lunga e stretta; and if he were in becca cesa, have him go into cinghiara porta di ferro alta; and if he were in guardia di intrare, have him go into guardia alta, following this sequence.

Guardia di Faccia

Marozzo: Having made him go into guardia di faccia, inform him that in this guard he can be both patient and agent in the same tempo; that is, if he is in coda lunga e larga, or in porta di ferro alta, stretta or larga, or in coda lunga e alta or stretta, by extending a thrust as his enemy is throwing a mandritto tondo or a fendente dritto, in the temp wherein the enemy attacks, his sword will be beneath that attack and will hit the enemy in the face with a thrust in that tempo.

Becca Cesa (Guardia di Lioncorno)

Marozzo: From here you need to make him understand the pro and contra of this guard. For one of great stature, this is a very singular guard both for attacking and defending. From this guard one can initiate imbroccate and fendenti falsi, as I’ve shown you on other occasions, as well as other things of which I don’t want to make mention at present.

Tactical Approach:

Nature of the Guards: Manciolino

We have both high guards and low guards. The objective of the high guards is to attack and then to follow with a parry; that of low guards is the opposite—to parry first and then to follow with a strike. Be advised that from the low guards only thrusts are natural attacks.

In the Art of the spada da filo, you should not depart from the low guards, because they are safer than their high counterparts. The reason is that when you are in a high guard you can be reached by a thrust or a cut to the legs, while in a low guard this danger does not exist.

Just as you should not strike without parrying, you should not parry without striking—always observing the correct tempi. If you were to always parry without striking, you would make your timidity plain to your adversary, unless you were to push the opponent back with your parry, in which case you would show your valor. Correct parries, in fact, are performed going forward and not backward; in this manner, you can not only reach your opponent, but you will also attenuate his blow against you, as from close by the opponent can only strike you with the part of the sword from mid-blade to the hilt; much worse it would be if he were to reach you with the other half of the sword.

Nature of the Guards: Marozzo

And again I tell you that you must never attack without defending, or defend without attacking, and if you do this you shall not fail.

All of the low guards are more for parrying than attacking.

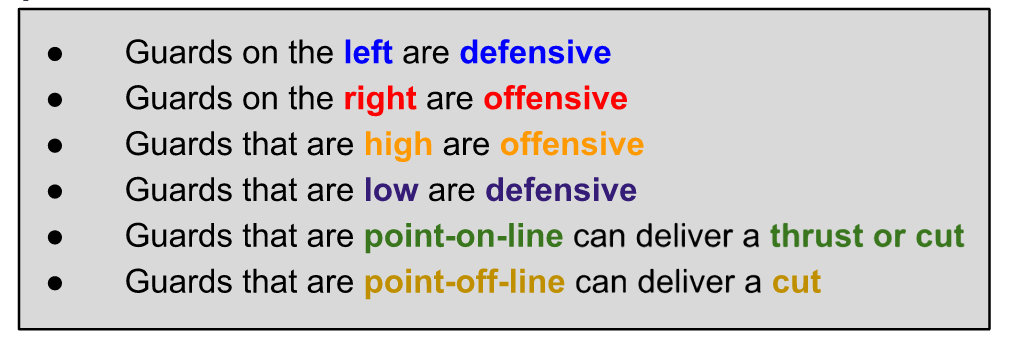

Nature of the Guards: Viggiani

ROD: I will tell it to you: every guard formed on the left side will be called “difensiva” and all of those on the right side will have the name “offensiva”; accordingly any time that the sword will be found on the left side (with the right foot in front, nonetheless, which we always assume, as much in guardia larga as in stretta), still, whether the arm be found higher, or less narrow, or lower than it between the stretta, and the larga, that will be understood as a defensive guard, and will be for defense; and all the times in which the sword will be found by the right side (also with the right foot forward) both in guardia alta perfetta and in imperfetta, both in guardia stretta and in larga, provided that the sword should be by the right side, such a guard will always be understood as offensive, and will be in order to offend. This will be our rule, and hold it fixed in your memory.”

General Bolognese Tactics: Anonimo

Also, you must know that if you find your enemy in a wide guard, then you will use your art to bring his sword into presence. If he has his point in presence, then you must my means of feinting , make him put his sword into a wide guard that allows you to control the line, such that his sword will point away from your person and off to the side of your body, and so you will then be able to perform whatever action you wish.

How to use a tactical approach:

Tactics in a sense, are generalizations, or commonalities, that when acted upon can form best practices. For example, when Manciolino says that in low guards only thrusts are natural attacks, what he's saying is; in order to deliver a cut from a low guard, you will have to raise your hand, or pull the sword back to chamber the cut, which is a big tempo, that your opponent can read and easily react to. This creates the basis of a tactic, if you can close measure with your opponent in a low guard, you can create a predictable response, the greatest danger comes from the thrust, and if they decide to break convention to deliver a cut, you'll have time to see it.

The goal of tactics, is to condense all the stuff you've learned from years of practice into easy to remember rules, or best practices, or if your following the other approach, to give you best practices to keep in mind as you study the intimate details of each guard. There is however a way to take all of this and condense it further…

Bolognese OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act):

Observe:

Is their sword:

Right or Left

High or Low

On-line or Off-line

Orient: Change your guard to attack appropriately (This is where you’ll need to know what each guard is best at—)

Decide: How you should attack or the best way to defend (This is where you’ll need to know how each guard can attack and defend—)

Act: Do the thing.

Hopefully this breakdown of the guards will help you begin your approach to understanding how to Observe and Orient yourself to your opponent, based on what guard they assume. Allow me to remind you of Marozzo and Manciolino’s words at the beginning of this article by paraphrasing and stitching their words together—You can deduce your enemies intentions by observing what guard they assume, but don’t stay fixed in a specific guard, so they can’t do the same to you (Frank n’ Marozzolino). That’s the OO in the OODA Loop, the DA comes from practice of drilling the basic attacks and defenses from each guard over-and-over as Marozzo suggests, but it can also be done by understanding the basic nature or limitations of each guard.

How often does Marozzo start a defense off by saying, “Your opponent could throw a mandritto, a riverso or a stocatta, lets assume…”, right? A lot. If we take Manciolino as our guide, we can observe that he heavily relies on three primary actions, turns of the hand, or mezza volta di mano, for defending; Guardia di Testa, Guardia di Faccia, and Mezzo Mandritto. These three simple defensive actions, create quick and snappy counter attacking opportunities, and when they’re used in succession they fulfill the tactical recommendation that Marozzo and Manciolino provide; that every attack should be followed by a defense action, and every defense should be followed with an offensive action. That would provide the foundation for our D and A. (We’ll discuss this further in later article)

Now, this subject can be infinitely complex, as the anonymous author alludes to in that opening quote (infinite and innumerable), or we can simplify it as much as humanly possible for quick and decisive reasoning. Inevitably, it’s up to you how much time you put into your practice, but I hope this article can be a resource to you on your journey no matter what choice you make along the way.

1. W. Jherek Swanger, Giovanni dall’Agocchie, Dell’Arte di Scrimia, The Art of Defense: on Fencing, the Joust, and Battle Formation, lulu press, May 5, 2018: Link

2. W. Jherek Swanger, Achille Marozzo, Opera Nova, The Duel, or the Flower of Arms for Single Combat, Both Offensive and Defensive, lulu press, April 22, 2018: Link

3. Tom Leoni, Antonio Manciolino, Opera Nova, The Complete Renaissance Swordsman, Freelance Academy Press, July, 2010: Link

4. Stephen Fratus, Anonimo Bolognese, With Malice & Cunning: Anonymous 16th Century Manuscript on Bolognese Swordsmanship, lulu press, Februrary 18, 2020: Link